An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

The impact of needle and syringe exchange programs on HIV-related risk behaviors in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis examining individual- versus community-level effects

Ping teresa yeh, caitlin e kennedy, kevin a armstrong, virginia a fonner, kevin r o’reilly, michael d sweat.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Co-first authors:

Authors’ contributions: MDS and KRO conceptualized the study. MDS, KRO, PTY, CEK, and VAF were responsible for the methodology of the study. PTY and XY were responsible for data curation, though all authors were involved in literature search and screening, data collection, and data analysis to varying degrees. KAA and MDS conducted formal meta-analysis, while PTY, XY, S, and CEK performed qualitative synthesis. The original draft was written by PTY and XY, with support from S and CEK. All authors were involved in reviewing and editing the manuscript and gave their approval for submitting the final manuscript.

Corresponding author: Ping Teresa Yeh, 615 N Wolfe St, Baltimore, MD 21205 USA, [email protected]

Issue date 2023 Oct.

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of needle and syringe exchange programs (NSP) on both individual- and community-level needle-sharing behaviors and other HIV-related outcomes in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC). A search of five databases for peer-reviewed trial or quasi-experimental studies reported through July 2021 identified 42 interventions delivered in 35 studies, with a total of 56,751 participants meeting inclusion criteria. Random-effects meta-analysis showed a significant protective association between NSP exposure and needle-sharing behaviors at the individual-level (odds ratio [OR]=0.25, 95% confidence interval [CI]= 0.16–0.39, 8 trials, n=3,947) and community-level (OR=0.39, CI=0.22–0.69, 12 trials, n=6,850), although with significant heterogeneity. When stratified by needle-sharing directionality, NSP exposure remained associated with reduced receptive sharing, but not distributive sharing. NSP exposure was also associated with reduced HIV incidence and increased HIV testing but there were no consistent associations with prevalence of bloodborne infections. Current evidence suggests positive impacts of NSPs in LMICs.

Keywords: HIV prevention, meta-analysis, needle/syringe exchange program (NSP), people who inject drugs (PWID), systematic review

Realizamos una revisión sistemática y un metanálisis del impacto de los programas de intercambio de agujas y jeringas (NSP, por sus siglas en inglés) de los comportamientos de uso compartido de agujas tanto a nivel individual como comunitario y otros resultados relacionados con el VIH en países de ingresos bajos y medianos (LMIC, por sus siglas en inglés). Realizamos búsquedas sistemáticas en cinco bases de datos hasta julio de 2021 en busca de ensayos revisados por pares o estudios cuasiexperimentales. En general, 42 intervenciones informadas en 35 estudios entre 56 751 participantes cumplieron los criterios de inclusión. El metanálisis de efectos aleatorios de ocho estudios a nivel individual y 12 a nivel comunitario con 11 075 participantes en total mostró una asociación protectora significativa entre la exposición a NSP y los comportamientos de compartir agujas (individual: OR = 0,25, IC del 95 %: 0,16–0,39; comunidad: OR=0,39, IC95%:0,22–0,69), aunque con una heterogeneidad importante. Cuando se estratificó por la direccionalidad del intercambio de agujas, la exposición a NSP permaneció asociada con un intercambio receptivo reducido, pero no con un intercambio distributivo. La exposición a NSP también se asoció con una incidencia reducida del VIH y un aumento de las pruebas del VIH, pero no hubo asociaciones consistentes para la prevalencia de infecciones transmitidas por la sangre. La evidencia actual sugiere impactos positivos de los NSP en los LMIC.

Introduction

Globally, there are approximately 15.6 million people who inject drugs according to a systematic review published in 2017. 1 People who inject drugs are at increased risk for contracting HIV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and other bloodborne diseases. 2 In many low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), globalization has brought both positive changes, such as improved transportation and international trade, and challenges, such as dissemination of illicit drugs and facilitation of HIV transmission. 3 Risk factors associated with HIV infection among people who inject drugs include poor health literacy, low health awareness, limited access to clean needles or other sterile drug injecting equipment, and the practice of sharing needles/syringes in groups. 4 , 5 In addition, people who inject drugs are often stigmatized and face discrimination, especially in LMICs where the practice of injecting drugs is typically illegal, creating further barriers to care-seeking. 6

Over the past 30 years, many countries have sought to reduce the risk of disease transmission from sharing contaminated needles through the adoption of harm reduction programs. These programs may include needle and syringe exchange programs (NSP), which strive to reduce high-risk behaviors like needle-sharing and needle reuse, 5 , 7 among other interventions including overdose prevention, safe injection sites, and opioid substitution therapy. NSPs reduce drug injection-related harm by providing sterile drug injection equipment and a location for safe syringe disposal, and they also often offer other risk reduction interventions, such as condom promotion/provision and other HIV-related services. 8

Multiple systematic reviews have shown that NSPs are effective in reducing HIV transmission among people who inject drug in high-income settings. 5 , 9 , 10 Despite stigma and criminalization of drug use, which impede NSP uptake, 11 there is now substantial evidence supporting the effectiveness of NSPs in LMICs as well. 12 However, the most recent reviews of the impact of NSPs in LMICs included studies published through 2011; there is thus a need to document the current state of the published evidence for NSPs. Further, previous reviews have not clearly distinguished between the impact of NSPs on individual-level versus community-level outcomes. At the individual-level, studies may compare individuals who use NSP services to other individuals who do not; this demonstrates the effect of NSPs on those who use them. At the community level, studies may compare communities where NSP services are available to other communities where such services are not available; this demonstrates the broader effect of NSPs, not only on those who use them, but also on the wider community. Separately examining the evidence for an impact at both levels allows us to better understand the full impact of NSPs.

We sought to evaluate the impact of NSPs on both individual- and community-level needle-sharing behaviors and other HIV-related outcomes in LMICs. This research was conducted as part of a larger series of systematic reviews conducted by the Evidence Project evaluating the effectiveness of behavioral interventions for HIV in LMICs. We conducted this review in accordance with PRISMA guidelines. 13

For the purposes of this review, we defined NSPs as programs that (1) provide sterile injecting equipment including needles and syringes to people who inject drugs, whether the needles and syringes are sold, exchanged, or given freely, and (2) help dispose of used needles and syringes safely.

Eligibility Criteria

Studies were included in the review if they met the following criteria:

data were presented from a LMIC, defined by combining the World Bank classifications 14 of low-income, lower-middle-income, or upper-middle-income economies at the time of the study;

needles and/or syringes were distributed, exchanged, or sold to people who inject drugs as part of the intervention;

the study population were people who inject drugs, according to any definition used by study authors (e.g. ever, past year, or other time frames);

an evaluation design was employed that compared post-intervention outcomes using either a pre/post or multi-arm study design (this could include randomized trials, non-randomized trials, observational studies, before-after studies, cross-sectional, or serial cross-sectional analyses);

specific outcomes of interest including use of new/sterile needles/syringes, return of used needles/syringes, needle borrowing/sharing, and other behavioral, psychological, social, care or biological outcome(s) related to HIV prevention were presented; and

the article was published in a peer-reviewed journal.

No language restrictions were used. When an article in a language other than English was found, it was translated into English for full-text review.

Search Strategy

We searched five electronic databases (PubMed, PsycINFO, Sociological Abstracts, the Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and EMBASE) for articles published from January 1, 1990 through July 25, 2021. We used the following search terms, adapted for each database ( Appendix A ): (“needle exchange” OR “needle distribution” OR “needle sales” OR “syringe sales” OR “syringe distribution” OR “syringe exchange” OR “syringe-exchange” OR “needle-exchange” OR “needle syringe programs” OR “needle syringe program” OR “needle syringe programme” OR “needle exchange programmes”) AND (HIV or AIDS).

To identify articles not obtained from electronic database searching, study staff hand-searched the table of contents of the following journals: AIDS , AIDS and Behavior , AIDS Care, AIDS Education and Prevention, and the International Journal of Drug Policy . Finally, we examined the reference lists of articles selected to further identify potential articles for inclusion. This process was iterated until no new articles were found.

Initial screening of studies was done by a member of the study staff, who excluded clearly non-relevant articles based on the titles and abstracts. Two study staff members conducted secondary screening, independently reviewing the abstracts of the remaining citations for inclusion. Differences in screening decisions were discussed to establish consensus. The final inclusion/exclusion of studies identified articles to be included in the qualitative synthesis and quantitative meta-analysis based on a thorough reading of the full-text article.

Data Extraction and Management

Each article meeting the inclusion criteria underwent data abstraction by two study staff members working independently. Data were entered into a standardized, detailed coding form including the following information:

study year, study location, and study design;

gender and age distribution, sample population, sample size, sampling strategy, loss to follow up, and comparison groups;

description of the NSP intervention (name of the program, recruitment strategy, facilitator/role of implementer, ways of exchange/distribution site, and intervention activities);

description of the outcome reported (needle/syringe needle sharing, other HIV- or sexually transmitted infection (STI)-related outcomes);

outcome measures, statistical tests used, and steps taken to control for covariates;

intervention effects and findings.

Completed coding forms from the two study staff members were compared for discrepancies, and differences were resolved through discussion and consensus with a third reviewer from the senior study staff.

Quality assessment

Rigor of included articles was assessed using an eight-item risk of bias tool developed for the larger series of systematic reviews by the Evidence Project, 15 conducted independently by two reviewers. Differences were resolved by consensus. The items were: (1) prospective cohort; (2) control or comparison group; (3) pre/post intervention data; (4) random assignment of participants to the intervention; (5) random selection of subjects for assessment; (6) follow-up rate of 80% or more; (7) comparison groups are equivalent on socio-demographic measures; and (8) comparison groups are equivalent at baseline on outcome measures.

Data Analysis

We focused on categorical outcomes of needle/syringe sharing behaviors and NSP exposure. We extracted count and proportion data that evaluated the association between NSP exposure and needle/syringe sharing behaviors based on between-group or pre-post comparisons. In meta-analysis, we only included studies that directly examined the association between needle/syringe sharing behaviors and NSP exposure. Adjusted effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for needle/syringe sharing behaviors associated with exposure to NSP were chosen over crude ones when available. Otherwise, the number and proportion of participants reporting the outcome of interest in both intervention and control/comparison groups or comparing before and after NSP exposure were extracted from each study. We then calculated the study-specific effect size expressed as an unadjusted odds ratio (OR) based on the available count and proportion data. For outcomes measured at multiple time points following NSP exposure, we used the last measurement period unless a study included a longer follow-up than most but also included a time point more similar to the remaining studies. When a study was conducted in two cities or countries and presented data separately, we considered them as separate interventions, so we calculated two location-specific effect sizes.

Meta-analysis was performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis, version 3 (CMA; Biostat, Englewood, NJ), using random-effects models to calculate pooled OR estimates and 95% confidence intervals. We assessed statistical heterogeneity using both Q and I 2 statistics. In the presence of substantial heterogeneity, we conducted sub-group analyses based on whether there was individual- or community-level outcome measurement and the type of needle/syringe-sharing behavior. First, we classified studies according to individual- or community-level outcome measurement. Separate analyses were conducted based on type of needle/syringe-sharing behavior: receptive sharing (i.e., receiving, borrowing, or reusing other persons’ used needles/syringes) and distributive sharing (i.e., distributing, lending, or passing on any used needles/syringes to other persons). Indirect sharing behaviors (e.g., backloading or frontloading needles/syringes 22 ) were excluded because few studies reported these outcomes. A third analysis combined both outcomes if a study reported both receptive and distributive sharing. In addition, if a study presented needle/syringe-sharing outcomes without specifying sharing directionality, we reported the non-directional estimates of effect sizes as a fourth analysis. Finally, we combined all study-specific estimates (including receptive, distributive, and reported non-directional sharing results) to assess overall NSP impact. We also created funnel plots of standard error by log odds ratio to assess potential reporting bias.

We excluded studies from meta-analysis if they did not report behavioral outcomes of needle/syringe sharing combinable for data synthesis or if we could not calculate the study-specific effect size because of missing or insufficient data, in which case authors were contacted for additional information. For example, articles were excluded if between-group comparisons were based on HIV status instead of needle/syringe sharing behaviors, or sharing behaviors were defined as “ever shared needles/syringes.” Studies were not combinable in meta-analysis if NSP exposure was defined by study authors in a unique way (e.g., exchanging seven or more free needles/syringes per week from the program 16 ), the study measured syringe sharing as a continuous variable (e.g., mean number of needles/syringes exchanged in the past 30 days 17 ), or it was not possible to attribute intervention effects to NSP exposure (e.g., the outcome measure was ever shared needles/syringes 18 ). We reported findings from all studies not included in meta-analysis in the qualitative synthesis, organized by outcome category.

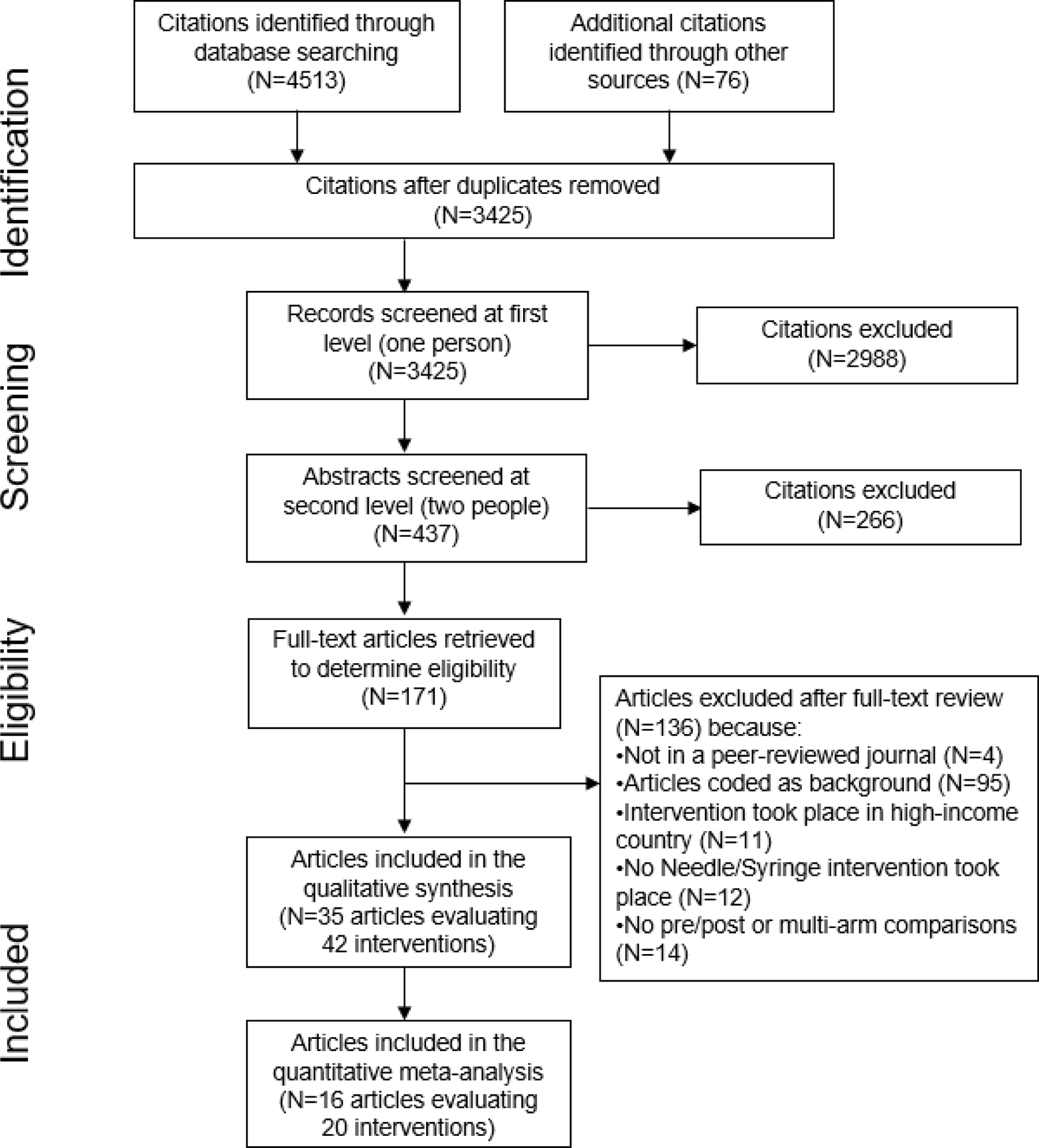

The search generated 4,513 citations from electronic databases and 76 citations by both hand-searching five journals and secondary searching ( Figure 1 ). After removing duplicates, 3,425 references were included for primary screening. We excluded 3,254 citations after examining their titles and abstracts. 171 full-text articles were retrieved to determine eligibility. Ultimately, 35 articles reporting on 42 interventions met the criteria for inclusion in this review and were included in the qualitative synthesis. 16 – 50

PRISMA flow diagram of the different phases of the systematic review.

Study characteristics

Table 1 presents summary characteristics of the 42 intervention effects (reported in 35 included articles) and descriptions of reported interventions related to NSP published between 1999 and 2021. 16 – 50 Two of these articles reported on Avahan, including community interventions for NSP in India, but presented different outcomes; 24 , 25 three other articles reported different outcomes and timepoints from the Cross-Border Project, a large serial cross-sectional study conducted in multiple sites in Vietnam and China. 22 , 26 , 27 The 42 intervention effects included 56,751 total participants; individual study sample sizes ranged from 105 to 20,640. Study designs included 21 cross-sectional studies, six serial cross-sectional studies, two quasi-experimental/non-randomized trials, two time-series studies, one before-after study, one cluster-randomized controlled trial, one prospective cohort study, and one retrospective case-control study. Most of the included articles were conducted in Asia (Bangladesh, China, India, Iran, Nepal, Pakistan, and Vietnam) and Russia. Several trial or cohort designs (one cluster randomized controlled trial, two group non-randomized controlled trials, and one prospective cohort study) were used to evaluate NSP programs in China. Three studies were conducted in Eastern Europe, including one time-series study in Georgia, one cross-sectional study in Croatia, and one cross-sectional study in Bulgaria. All included studies were from lower-middle and upper-middle-income countries; none were from countries classified as low-income by the World Bank. Study participants were predominantly male and young; ages ranged from 18–50 years old. Only one cross-sectional study, from Mexico, focused on female sex workers who injected drugs.

Description of included studies and reported NSP interventions

HCV: hepatitis C virus

IQR: interquartile range.

NGO: non-governmental organization.

NSP: needle and syringe program, or needle and syringe exchange program.

STI: sexually transmitted infection

Intervention characteristics varied across studies. Peer-driven and social networks were the most common methods to recruit people who inject drugs. Peer educators, non-governmental organizations, and outreach health workers usually partnered with the NSP intervention to facilitate on-site and outreach needle/syringe exchange. Secondary exchange by peers and pharmacy vouchers also served as sources of clean needles and syringes. Most participants were also exposed to other intervention activities, such as HIV information sessions, health education, distribution of free condoms and injection equipment, and voluntary HIV counseling and testing.

Table 2 presents a summary of comparative outcomes reported, including needle-sharing behaviors and HIV and other STI-related outcomes, by study. Overall, 21 interventions presented outcomes measured at the individual-level and 19 at the community-level. We could not determine level of outcome measurements in two interventions. Among 30 interventions that reported needle-sharing behavior outcomes, 15 did not specify the direction of sharing. One reported the outcome of lifetime/ever shared needles/syringes. The other 14 included descriptions of how needles/syringes were shared, which we used to assign receptive and distributive needle-sharing outcomes. The most frequent additional HIV-related outcomes reported were HIV incidence and HIV prevalence, while a few studies measured hepatitis B, hepatitis C, syphilis, and chlamydia prevalence.

Comparative outcomes reported by included studies a

Cell shade in light green: outcome reported; in dark green: outcome reported and included in meta-analysis.

Combined receptive and distributive outcomes per study, when both reported.

Shared injecting paraphernalia include containers, cooker, cotton, filter, rinse water, solutions, etc.

Other injection outcomes include return of needles, frontloading/backloading, needle sharing frequency, injection frequency, number of sharing partner, etc.

Other STIs include chlamydia, gonorrhea, HBV, HCV, and syphilis.

Outcome reported is HIV testing prior to the survey. Duration or time frame of the measurement is unknown.

Needle-sharing outcome reported is ever shared needles/syringes.

Unique categorical measure of exposure: accessibility of NSP services (low, middle, high).

Unique categorical measure of exposure: low or high NSP user.

Unique categorical measure of exposure: whether received 7 or more free needles/syringes.

Table 3 presents the risk of bias assessment for each intervention. Most interventions did not employ a cohort design (N=34) or perform randomization when enrolling participants and assigning interventions (N=40). Most interventions (N=32) were evaluated through cross-sectional or serial cross-sectional methods. Therefore, those study results are subject to limitations due to cross-sectional design, weak participant representativeness, and non-equivalence of comparison groups (if applicable). One prospective cohort study, two before-after studies and two time-series studies were rated low rigor because of non-randomized designs and low follow-up rates, which were all below 80%. Only one of two non-randomized trials had a follow-up rate higher than 80%. Only one randomized trial was included, which showed the greatest rigor. This cluster randomized controlled trial in China investigated a needle social marketing strategy at the community level among 823 young people who inject drugs from 2002 to 2003. 43 Although its findings suggested significant NSP intervention benefits, it did not randomly select participants for assessment and the comparison groups were not equivalent at baseline. 43 In fact, none of the included studies reported equivalent group characteristics at baseline.

Quality assessment of included articles.

Study outcomes included in meta-analysis.

Below, we present findings for needle-sharing, HIV incidence and prevalence, and other HIV-related outcomes.

Needle/syringe sharing

Overall, 25 articles measured the effects of NSP exposure on needle/syringe sharing behaviors. 16 – 21 , 25 – 27 , 29 – 34 , 38 , 39 , 43 – 50 Of these, 16 articles provided comparable outcome data and were included in meta-analysis; 13 presented additional outcomes that were analyzed qualitatively.

Meta-analysis

Sixteen articles presenting 20 interventions 19 , 20 , 25 , 27 , 29 , 31 – 34 , 38 , 39 , 43 – 47 were meta-analyzed, resulting in a total sample size of 11,075, with 6,024 people who inject drugs exposed to the intervention and 5,051 in the reference group. Meta-analysis results are summarized in Table 4 .

Summary of meta-analyses of needle-sharing outcomes.

Receptive, Distributive, and Any (non-directional) needle sharing combined per study, when any of the three were available for a study.

Non-directional needle sharing estimate reported.

Receptive and Distributive needle sharing combined per study, when both were reported.

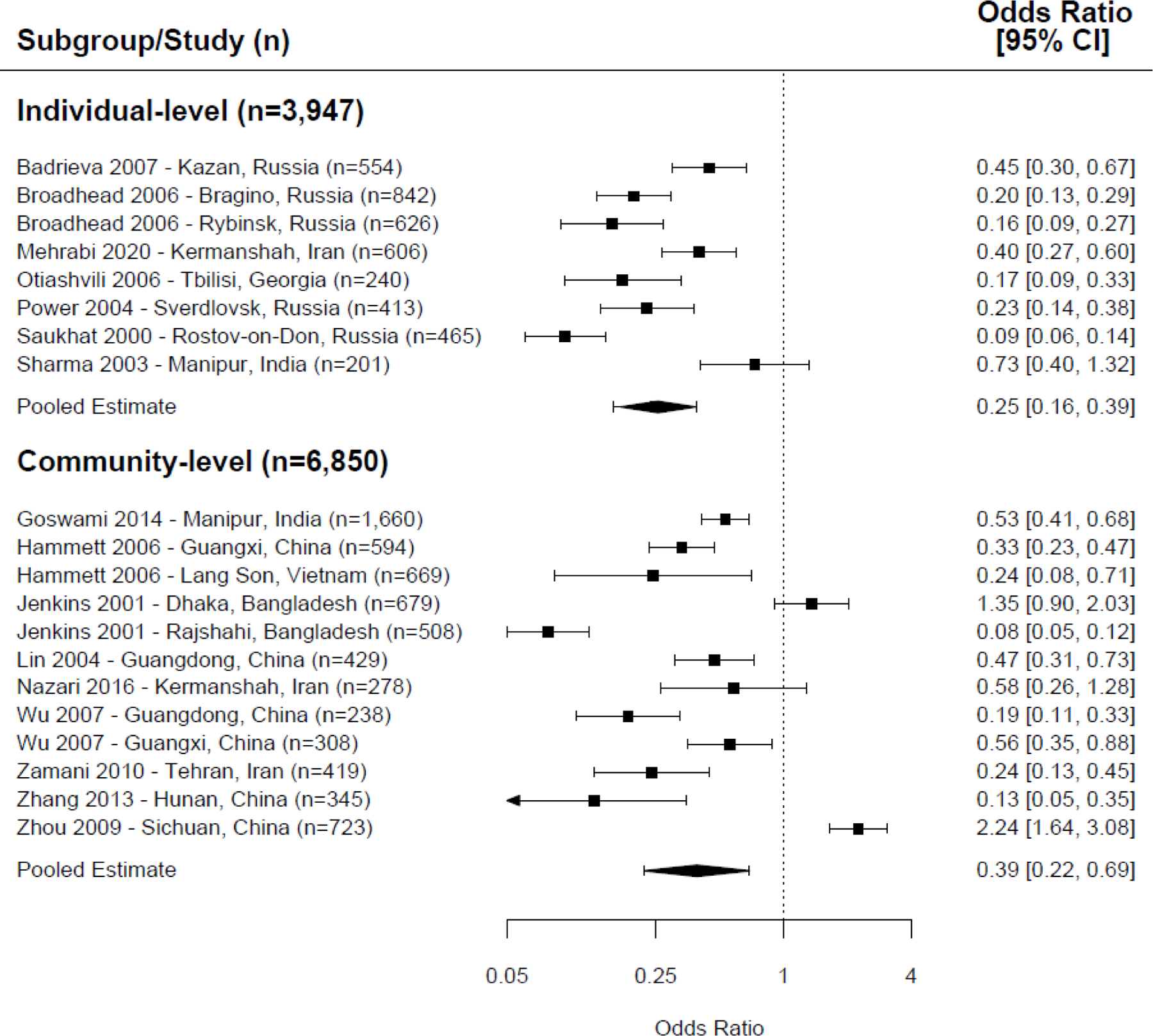

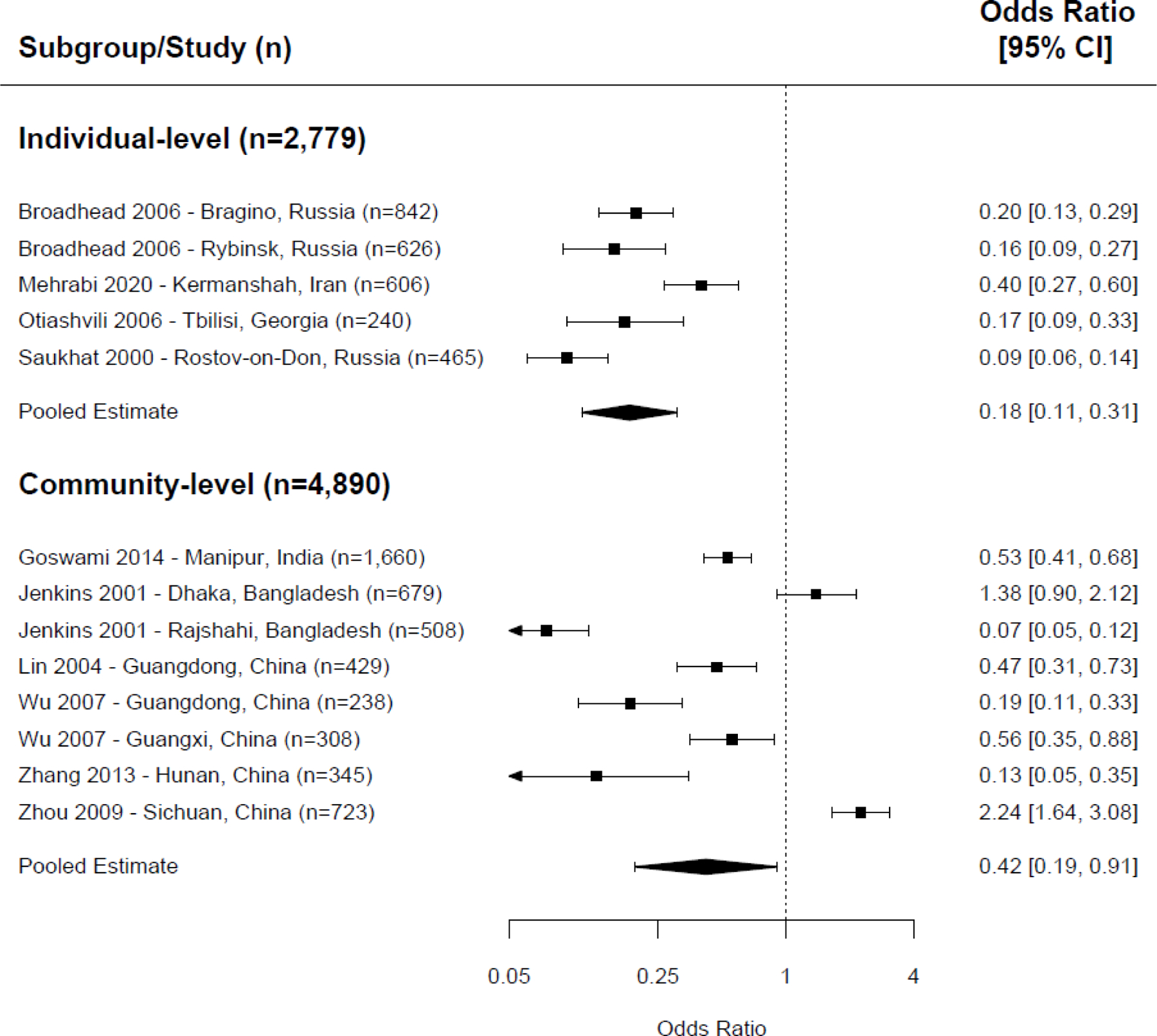

For overall needle-sharing behaviors (combining receptive, distributive, and non-directional needle sharing), NSP exposure was associated with a statistically significant protective effect when assessed at both the individual- and community-level ( Figure 2 ; individual-level: odds ratio [OR]=0.25, 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.16–0.39, p <0.001, I 2 =86%, 8 trials, n=3,947; community-level: OR=0.39, CI=0.22–0.69, 12 trials, n=6,850, p =0.001, I 2 =95%). 19 , 20 , 25 , 27 , 29 , 31 – 34 , 38 , 39 , 43 – 47 However, there was high statistical heterogeneity, likely due to significant differences in outcome measurements, intervention modality, intervention duration, and exposure types.

Meta-analysis of overall needle sharing (receptive, distributive, and non-directional needle sharing combined), exposure to NSP versus control/comparison group.

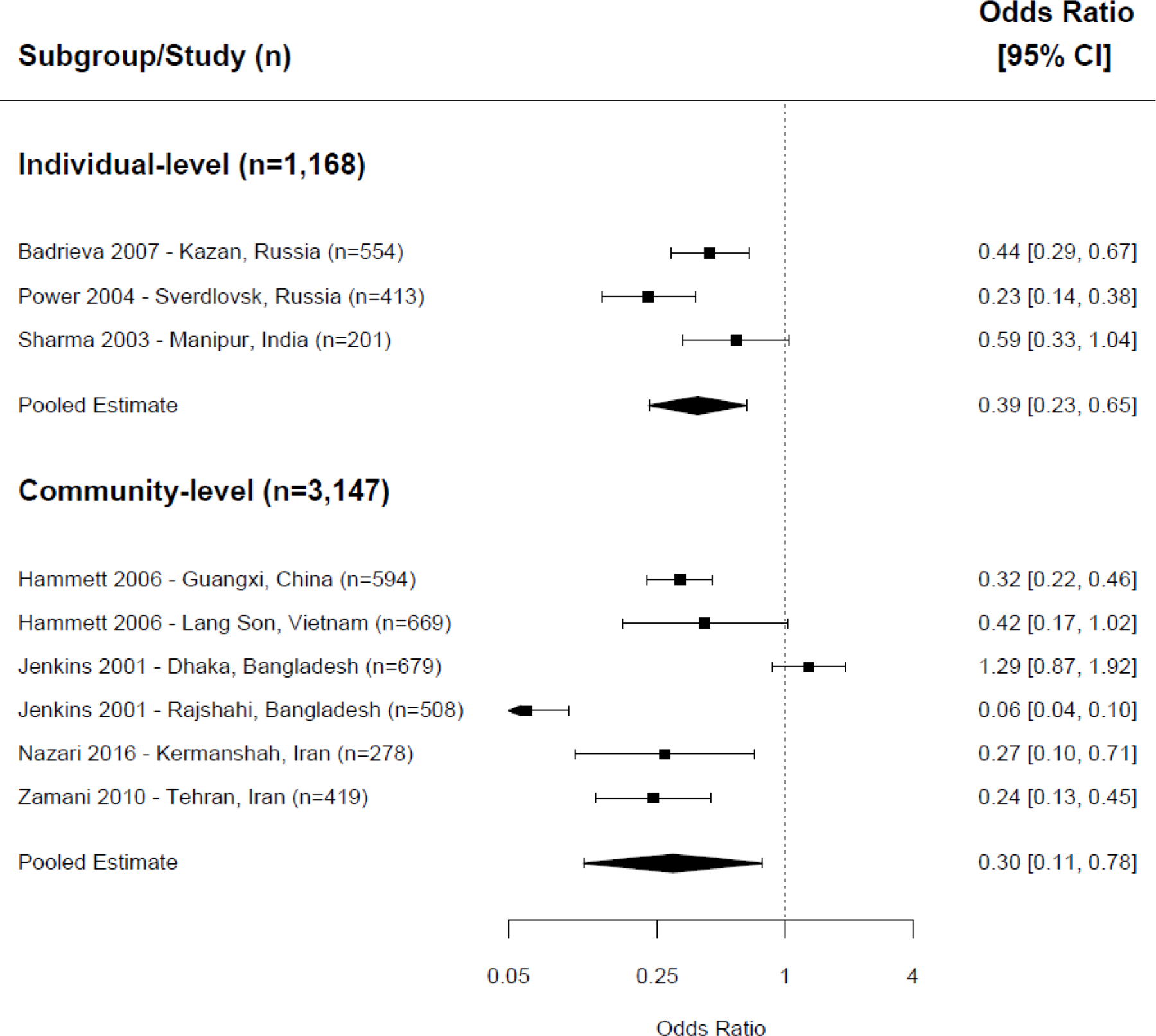

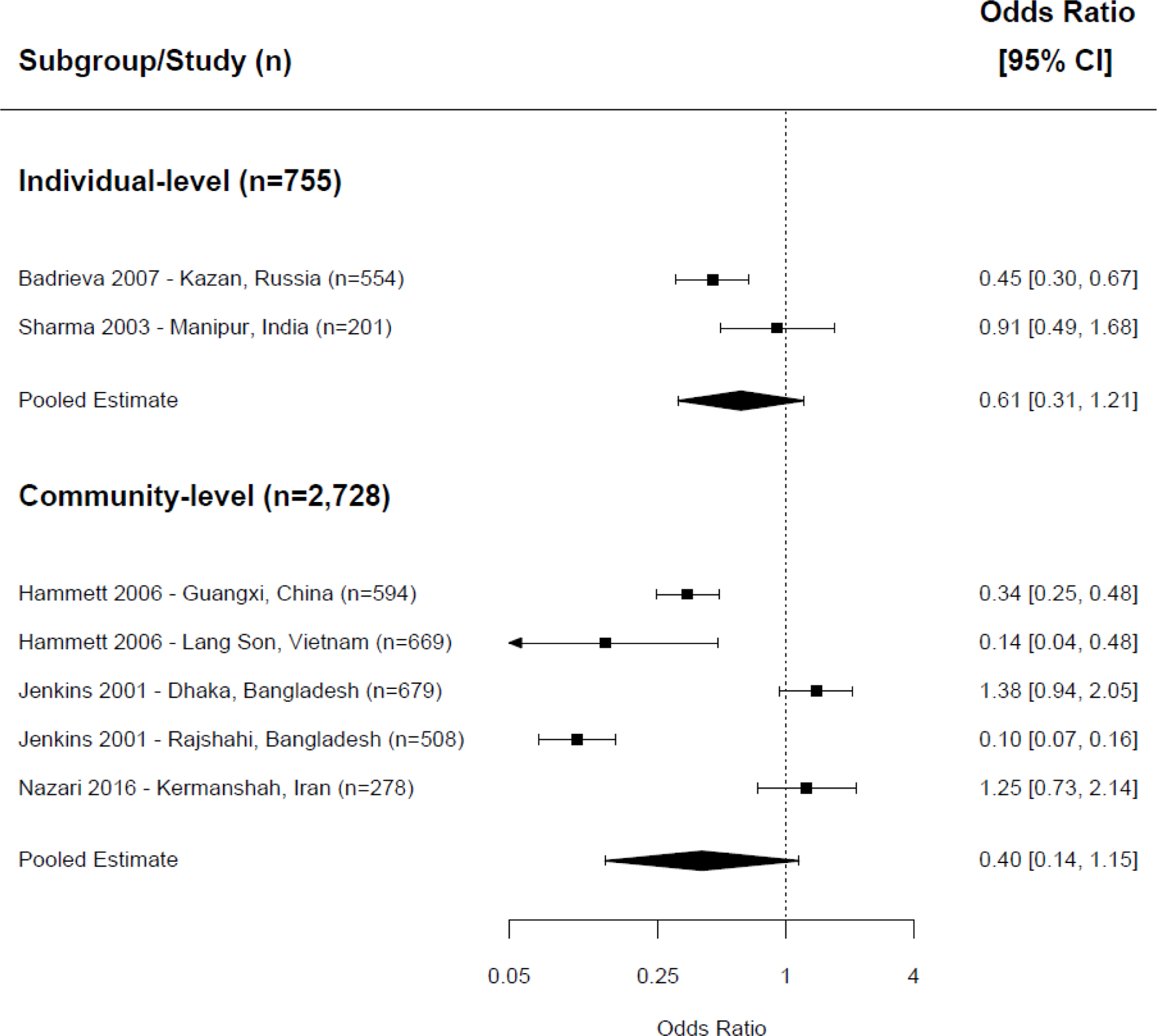

Separate analyses examined pooled effects of NSP exposure on receptive sharing and distributive sharing. For receptive sharing, we combined the effects of nine interventions in meta-analysis. We found that NSP exposure was associated with a lower odds of receptive sharing behaviors ( Figure 3 ) at both the individual-level (OR=0.39, CI=0.23–0.65, p <0.001, 3 trials, I 2 =70%) and the community-level (OR=0.30, CI=0.11–0.78, p =0.001, 6 trials, I 2 =95%). 19 , 27 , 29 , 32 , 34 , 39 , 44 Seven interventions examining the associations between NSP exposure and distributive sharing did not show a statistically significant association when combined in meta-analysis at either the individual- or community-level ( Figure 4 ; individual-level: OR=0.61, CI=0.31–1.21, p =0.16, 2 trials, I 2 =72%; community-level: OR=0.40, CI=0.14–1.15, p =0.09, 5 trials, I 2 =96%). 19 , 27 , 29 , 32 , 39

Meta-analysis of receptive needle sharing, exposure to NSP versus control/comparison group.

Meta-analysis of distributive needle sharing, exposure to NSP versus control/comparison group.

When we combined the effect sizes from studies that did not specify directionality of sharing ( Figure 5 ), 20 , 25 , 29 , 31 , 33 , 38 , 43 , 45 – 47 a protective association between exposure to NSP and needle/syringe sharing was observed among the five interventions at the individual-level (OR=0.18, CI=0.11–0.31, p <0.001, 5 trials, I 2 =83%). We also observed 58% lower odds of needle/syringe sharing at the community-level (OR=0.42, CI=0.19–0.91, p =0.027, 8 trials, I 2 =96%), although heterogeneity was significant.

Meta-analysis of non-directional needle sharing, exposure to NSP versus control/comparison group.

In addition, six interventions reported both receptive and distributive sharing outcomes. 19 , 27 , 29 , 39 The pooled within-study effect of needle sharing was estimated per study, and we found statistically significant lower odds of this combined receptive and distributive needle/syringe sharing outcome among people who inject drugs who participated in NSP (OR=0.54, CI=0.34–0.87, p =0.01, 2 trials, I 2 =44%) with moderate heterogeneity at the individual-level. However, the protective association did not retain statistical significance when analyzed at the community-level (OR=0.31, CI=0.09–1.10, p =0.07, 4 trials, I 2 =97%).

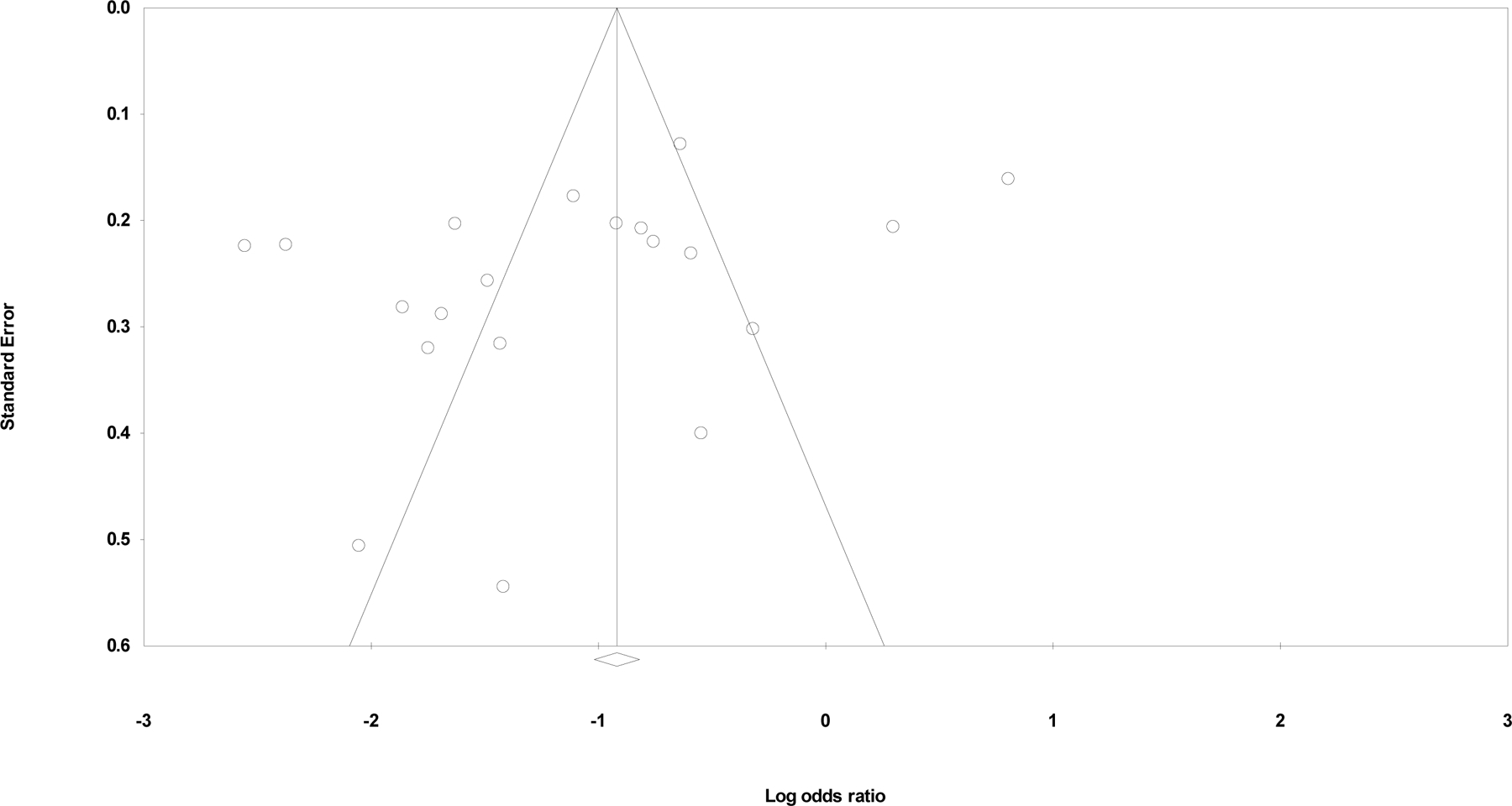

Figure 6 shows a scatter plot of 20 intervention effect estimates (log odds ratio) measured in the meta-analysis against each study’s standard error. We observed a slightly asymmetric shape with more effect estimates from large studies scattered widely in a horizontal line at the middle top of the graph. The funnel plot suggests most included studies with similar standard errors reported protective effects of NSPs, potentially reflecting some reporting bias.

Funnel plot of standard error by log odds ratio, N=20.

Qualitative synthesis

In addition, 13 articles presented associations between NSP exposure and needle/syringe sharing related outcomes, but could not be included in meta-analysis as described in the methods section above. 16 – 21 , 31 , 32 , 34 , 39 , 48 – 50 Overall, six articles reported an association between NSP exposure and reduced needle/syringe sharing behaviors, although their definitions of NSP exposure varied widely. 16 , 17 , 21 , 48 – 50 Four cross-sectional studies in Iran published between 2004 and 2020 suggested that the odds of reporting needle/syringe sharing behaviors were lower among people who inject drugs who had high accessibility to NSP, or who received more sterile needles/syringes from NSP, or who attended NSP regularly, compared with their comparator groups. 16 , 48 – 50 Another cross-sectional study in 10 central and eastern European cities found statistically significant reductions in receptive needle/syringe sharing. 21 Less needle/syringe sharing was reported among NSP users in China 18 and Russia 17 as well. Other articles reported on sharing injection paraphernalia (cookers, filters, rinse water, solutions, containers, etc.) but effects of NSP varied widely – positive, neutral and negative – depending on specific study sites, comparators, and length of time from intervention. 16 , 17 , 19 – 21 , 31 , 32 , 34 , 39 , 48 , 49

HIV incidence and prevalence

HIV incidence was measured or estimated in 5 articles. 22 , 26 , 34 , 36 , 43 One cohort study in China found a statistically significant and substantial decrease in HIV incidence comparing participants in a cohort before NSP was available to a post-NSP cohort. 36 A second study from Russia presented government statistics on new HIV diagnoses (per 100,000 population) in the cities where NSPs were implemented, finding decreases in new diagnosis rate over the study period in one city (Verknaya Salda) and increases then decreases in new diagnoses in two other cities (Pervouralsk and Ekaterinburg). 34 The remaining studies calculated estimated measures of HIV incidence, based on the assumption that prevalent cases of HIV among new injectors were comparable to incidence. The strongest study design, a cluster-randomized trial in China, found that the NSP intervention was associated with reduced HIV incidence in one study site (Guangdong), but not the other (Guangxi); combined, the effect was not statistically significant. 43 One serial cross-sectional study, the Cross-Border Project, conducted in Vietnam and China reported estimated HIV incidence data in two articles. 22 , 26 Both articles found that estimated HIV incidence decreased substantially to low levels among new injectors by 24 months, although one article 22 found that estimated incidence continued to decline by 36 months while the other 26 saw some rebound after 36 months, particularly in one study site (Ning Ming, China). Four of these five articles also reported other behavioral or disease outcomes; generally, where HIV incidence decreased, sharing behaviors and other infections decreased as well.

Fifteen articles (20 interventions), mostly cross-sectional studies, reported associations between NSP and HIV prevalence. 18 , 22 , 23 , 25 – 27 , 30 , 31 , 35 , 37 , 38 , 40 – 43 Across these, we found no consistent association between NSP exposure and HIV prevalence.

Other HIV-related outcomes

Several studies reported positive changes in other HIV-related outcomes, such as significantly higher HIV testing uptake. 32 , 49 Additional studies showed inconsistent associations between NSP interventions and incidence or prevalence of other infectious diseases (chlamydia, gonorrhea, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and syphilis). 25 , 28 , 31 , 36 , 41 , 43

We systematically reviewed the current evidence base for the effectiveness of NSP at both the individual- and community-level, with a focus on needle-sharing behaviors and other HIV-related outcomes. Although few rigorous trials were identified, we did find a relatively strong evidence base of mostly cross-sectional studies examining the association between NSPs and needle sharing, and a more limited evidence base for HIV incidence, HIV testing, and other infectious diseases.

In meta-analysis, NSPs were associated with fewer people who inject drugs receiving used needles/syringes at both the individual- and community-level. The effect of NSPs on distributive sharing was not statistically significant at either level. When we combined distributive and receptive needle/syringe sharing outcomes, we observed a more significant protective association for NSPs whose outcomes were measured at the individual-level than at the community-level. These findings are consistent with a direct benefit of NSPs for those who use them. However, this benefit seems to be primarily for receptive sharing – the impact of which is substantial enough that it can be seen even when measured at the community-level. Compared with other reviews exploring the effectiveness of NSP in reducing HIV incidence, 5 , 10 , 12 , 51 our approach to stratifying effects by level and directionality provides additional insight on specific risks. While the provision of clean, sterile needles/syringes is fundamental and necessary to reduce receptive sharing, it is not sufficient to reduce distributive sharing.

Beyond needle/syringe sharing, we also found that NSP exposure was associated with lower HIV incidence and higher HIV testing uptake. Findings on HIV prevalence and other infectious diseases were mixed; however, we attribute this to the cross-sectional nature of the study designs which could not assess causal relationships. Overall, findings from our review support the conclusion that NSPs are associated with better HIV outcomes.

We defined NSPs as programs both providing clean, sterile injecting equipment and also disposing of used injection equipment according to safety regulations. The included studies involved a variety of service delivery mechanisms, including pharmacy-based services and peer outreach. While several studies mentioned the cost of clean needles through pharmacies, not enough studies provided sufficient detail to analyze whether distribution modality made a difference in needle-sharing behaviors and other outcomes. However, programs which sell or otherwise provide needles/syringes to people who inject drugs through pharmacies have a number of benefits: they are relatively inexpensive to operate, are often open for long hours, are typically accessible in low-resourced settings including in rural areas, and may provide discretion to their clients. Though some research has already explored the benefits of pharmacy-based compared to facility-based NSP, 52 further work could examine the benefits of such programs.

In addition to understanding the individual- or community-level measurement and directionality of needle-sharing behaviors, it is also important to understand how NSPs influence needle disposal behaviors. Studies in high-income settings have posited that unsafe needle disposal outside of hospitals or other healthcare settings by people who inject drugs could increase risk of bloodborne infectious disease in the broader community; 53 , 54 NSPs could ameliorate this risk by reducing unsafe disposal behaviors. 55 However, none of the included articles reported the exchange rate of used needles/syringes or other unsafe disposal behaviors. No included articles provided details on whether all used needles/syringes were retrieved when study participants interacted with the NSP, or whether study participants were able to obtain new injection kits without having to return used needles/syringes. Future research could explore unsafe disposal behaviors in LMICs.

Because we included studies published from 1990 to 2021, we were able to qualitatively explore temporal changes in NSP implementation in countries like Bangladesh, China, India, Iran, Pakistan, Russia, and Vietnam which provided data from both the 1990s/2000s and more recently. Earlier NSP activities primarily focused on needle distribution and needle exchange, along with counselling and health education/promotion about drug use reduction and HIV prevention. Earlier programs tended to use non-governmental organizations or primary care workers, but more recent studies tended to involve peer educators as facilitators.

Participants in these included studies were predominantly male. While this may reflect local patterns of drug use in these particular LMIC settings, women who inject drugs are often underrepresented in the scientific and medical literature. 56 Previous research has found gender differences among people who inject drugs, in terms of HIV risk and needle-sharing behaviors. 2 , 57 Women who inject drugs have a higher likelihood of engaging in unsafe sexual practices and a compounded risk of contracting HIV. 58 The complex intersection of HIV and injection drug use could benefit from a socio-ecological approach and gender-specific interventions tailored to specific populations’ needs. For example, recruiting female outreach workers or female peer educators, coupled with women-focused behavioral interventions, has been found effective. 59

Despite heterogeneity in intervention modalities and outcome measures, we found evidence that NSP is associated with reduced receptive and overall needle-sharing behaviors in both individual-level and community-level NSP in LMICs. Interestingly, these behaviors which typically are only measured at the individual-level were strong enough to demonstrate community-level effects. NSPs appear to be an effective intervention component to prevent HIV and other blood-borne infections by improving access to sterile needles/syringes and discouraging people who inject drugs from sharing used injection equipment. There is also a literature gap in African, Latin American, and Caribbean countries where NSP implementation is less common, though HIV prevalence may be high.

NSPs have been promoted as an effective intervention to reduce HIV, hepatitis C, and hepatitis B transmission among people who inject drugs in high-income settings. 51 We identified several LMICs in Asia and Eastern Europe that implemented large-scale NSPs as part of harm reduction programs. According to the latest Global State of Harm Reduction report, although NSPs are officially allowed and scaling up in many Asian and Eastern European countries where our included studies were based, their service capacity is relatively limited because of weak political support and shrinking funds. 60 For example, illicit drug use is an indictable act in China. If arrested and found to have relapsed, people who inject drugs could be directed to receive compulsory methadone maintenance therapy or referred to mandatory detoxification centers. 45 Stringent drug-control regulations and police confinement appear to limit access to NSPs by people who inject drugs. Some Asian countries, including Laos, the Philippines, and Mongolia, still prohibit the implementation of NSPs even though NSPs have been shown as an effective harm-reduction approach in nearby countries based on the 2020 Harm Reduction International report. 60 Punitive drug policies, limited funding, and a high level of stigma also substantially limit the coverage and quality of NSPs in Eastern European countries. 60 , 61 For example, Bulgaria suspended a NSP site in July 2020 due to unstable funding after one year of reopening operation. 62 Punitive and stringent regulations around injection drug use also make people who inject drugs seeking NSPs in Russia and Ukraine at high risk of discrimination, police hostility, and arrest, 60 which could be further exacerbated by the current conflict. Therefore, adapting NSPs to local policies and maintaining NSPs’ accessibility in LMICs deserve further investigation.

This review has several strengths. We explored both individual- and community-level outcome measurements and included different types of needle/syringe-sharing behaviors. Use of an eight-item risk of bias tool allowed us to assess the rigor of included studies. By not restricting inclusion by language and searching multiple databases, we minimized the possibility of missing relevant studies. We also synthesized the most recent empirical evidence of NSP’s impact on HIV-related outcomes through July 2021. Finally, we tried to achieve quality assurance by having two independent study reviewers/assistants screen articles, abstract data, and resolve any discrepancies.

However, our study also has several limitations. First, our search strategy was focused on HIV-related outcomes; we therefore may have missed other studies examining the impact of NSPs on needle/syringe sharing behaviors without mentioning HIV, or that focused exclusively on hepatitis C or other outcomes. Second, most of the included studies were cross-sectional in design and did not provide data adjusted for confounders, which limits the inferences we can draw. Further, there was significant heterogeneity across studies in intervention length/frequency, recruitment strategy, choice of facilitators/implementers, delivery methods, and other concurrent intervention activities. Due to the limited number of studies for each outcome, we were also unable to conduct meta-regression to examine study-level factors associated with positive outcomes. Future studies could consider evaluating NSP designs or procedures in difference settings and regions. How to customize program designs and intervention activities considering local patterns of drug use, population characteristics, and regulations to enhance NSP’s positive impacts is worth further academic attention. Third, we were unable to include several effect measures in meta-analysis due to insufficient information, and we failed to obtain responses from correspondent authors after email inquiries. This reduced the number of included interventions for the meta-analysis. Fourth, there were no standardized measurements for NSP exposure, and most studies relied on participants’ self-reported behavioral outcomes. Due to the nature of the intervention, convenience and purposive sampling methods were also the most used recruitment methods. Therefore, the pooled estimates of NSP impacts are likely affected by measurement bias, social-desirability bias, and selection bias. Finally, implementation science research in both high- and low-resource settings has generally shifted from focusing on NSP to providing “comprehensive HIV prevention and care” including NSP, opioid agonist treatment, methadone maintenance treatment, and antiretroviral therapy for people who inject drugs; 63 two recent studies of such comprehensive programs in LMICs (HPTN 074 in Eastern Europe and Southeast Asia, 64 the DRIVE study in Vietnam 65 ) have found very low HIV incidence among people who inject drugs. Better understanding how NSPs contribute to the overall success of such comprehensive packages is challenging but worth future investigation.

In conclusion, we examined the association of NSPs with HIV-related outcomes in LMICs over the past three decades. We found that exposure to NSP across studies was overall associated with reduced needle/syringe sharing and reduced HIV incidence among people who inject drugs. The meta-analysis also found that NSPs showed a statistically significant beneficial association with reducing receptive sharing, non-directional sharing, and overall needle-sharing behaviors among people who inject drugs when measured at the individual-level. However, we did not find a statistically significant protective association with distributive needle-sharing behaviors at either the individual- or community-level.

Acknowledgements:

The authors wish to thank Elizabeth Jere, Carolyn Pleisca, Sarah Mauch, Alison Groves, Rachel Hower, Devaki Nambiar, Jennifer Gonyea, Andrea Ippel, Kirk Fiereck, Prossy Namusisi, and Indira Prihartono for their coding work on this project, Lindsay Cooper for her assistance in checking the Spanish language abstract, and Elena Tuerk and Julie Denison for their contributions to study development and supervision.

This work was supported by the US National Institute of Mental Health (grant numbers R01MH071204, R01MH090173, R01MH125798).

Appendix A. Search strategy for all databases, last searched on July 25, 2021

(“needle exchange” OR “needle distribution” OR “needle sales” OR “syringe sales” OR “syringe distribution” OR “syringe exchange” OR “syringe-exchange” OR “needle-exchange” OR “needle syringe programs” OR “needle syringe program” OR “needle syringe programme” OR “needle exchange programmes”) AND (HIV or AIDS)

Sociological Abstracts

(‘needle exchange’ OR ‘needle distribution’ OR ‘needle sales’ OR ‘syringe sales’ OR ‘syringe distribution’ OR ‘syringe exchange’ OR ‘syringe-exchange’ OR ‘needle-exchange’ OR ‘needle syringe programs’ OR ‘needle syringe program’ OR ‘needle syringe programme’ OR ‘needle exchange programmes’) AND (HIV or AIDS)

Hand search of the following journals:

AIDS and Behavior

AIDS Education and Prevention

the International Journal of Drug Policy

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Declarations

Ethics approval: Because this is a systematic review of published data, no ethical approval was required.

Consent to participate: Not applicable

Consent for publication: Not applicable

Code availability: Not applicable

Registration: Not registered on PROSPERO.

Availability of data and material

Available upon request to the corresponding author.

- 1. Degenhardt L, Peacock A, Colledge S, et al. Global prevalence of injecting drug use and sociodemographic characteristics and prevalence of HIV, HBV, and HCV in people who inject drugs: a multistage systematic review. The Lancet Global Health 2017; 5(12): e1192–e207. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Strathdee SA, Galai N, Safaiean M, et al. Sex differences in risk factors for hiv seroconversion among injection drug users: a 10-year perspective. Arch Intern Med 2001; 161(10): 1281–8. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Mesquita F, Jacka D, Ricard D, et al. Accelerating harm reduction interventions to confront the HIV epidemic in the Western Pacific and Asia: the role of WHO (WPRO). Harm reduction journal 2008; 5: 26. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Des Jarlais DC, Kerr T, Carrieri P, Feelemyer J, Arasteh K. HIV Infection among Persons who inject Drugs: Ending Old Epidemics and Addressing New Outbreaks. AIDS (London, England) 2016; 30(6): 815–26. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Fernandes RM, Cary M, Duarte G, et al. Effectiveness of needle and syringe Programmes in people who inject drugs – An overview of systematic reviews. BMC public health 2017; 17. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Des Jarlais DC, Pinkerton S, Hagan H, et al. 30 Years on Selected Issues in the Prevention of HIV among Persons Who Inject Drugs. Advances in Preventive Medicine 2013; 2013: 346372. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. van den Hoek JA, van Haastrecht HJ, Coutinho RA. Risk reduction among intravenous drug users in Amsterdam under the influence of AIDS. Am J Public Health 1989; 79(10): 1355–7. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Kral AH, Bluthenthal RN. What is it about needle and syringe programmes that make them effective for preventing HIV transmission? International Journal of Drug Policy 2003; 14(5): 361–3. [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Abdul-Quader AS, Feelemyer J, Modi S, et al. Effectiveness of Structural-Level Needle/Syringe Programs to Reduce HCV and HIV Infection Among People Who Inject Drugs: A Systematic Review. AIDS and behavior 2013; 17(9): 2878–92. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Aspinall EJ, Nambiar D, Goldberg DJ, et al. Are needle and syringe programmes associated with a reduction in HIV transmission among people who inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International journal of epidemiology 2014; 43(1): 235–48. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Salter ML, Go VF, Minh NL, et al. Influence of Perceived Secondary Stigma and Family on the Response to HIV Infection Among Injection Drug Users in Vietnam. AIDS Education and Prevention 2010; 22(6): 558–70. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Des Jarlais DC, Feelemyer JP, Modi SN, Abdul-Quader A, Hagan H. High coverage needle/syringe programs for people who inject drugs in low and middle income countries: a systematic review. BMC public health 2013; 13: 53. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews 2021; 10(1): 89. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups 2020. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (accessed June 1 2020).

- 15. Kennedy CE, Fonner VA, Armstrong KA, et al. The Evidence Project risk of bias tool: assessing study rigor for both randomized and non-randomized intervention studies. Systematic Reviews 2019; 8(1): 3. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Vazirian M, Nassirimanesh B, Zamani S, et al. Needle and syringe sharing practices of injecting drug users participating in an outreach HIV prevention program in Tehran, Iran: a cross-sectional study. Harm reduction journal 2005; 2: 19. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Sergeyev B, Oparina T, Rumyantseva TP, et al. HIV Prevention in Yaroslavl, Russia: A Peer-Driven Intervention and Needle Exchange. Journal of Drug Issues 1999; 29(4): 777–803. [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Luo W, Wu Z, Poundstone K, et al. Needle and syringe exchange programmes and prevalence of HIV infection among intravenous drug users in China. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2015; 110(Suppl 1): 61–7. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Badrieva L, Karchevsky E, Irwin KS, Heimer R. Lower injection-related HIV-1 risk associated with participation in a harm reduction program in Kazan, Russia. AIDS Educ Prev 2007; 19(1): 13–23. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Broadhead RS, Ryabkova M, Borch C, et al. Peer-driven HIV interventions for drug injectors in Russia: First year impact results of a field experiment. International Journal of Drug Policy 2006; 17(5): 379–92. [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Des Jarlais DC, Friedmann P, Grund J-P, et al. HIV risk behaviour among participants of syringe exchange programmes in central/eastern Europe and Russia. International Journal of Drug Policy 2002; 13(3): 165–70. [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Des Jarlais DC, Kling R, Hammett TM, et al. Reducing HIV infection among new injecting drug users in the China-Vietnam Cross Border Project. AIDS 2007; 21 Suppl 8: S109–14. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Eicher AD, Crofts N, Benjamin S, Deutschmann P, Rodger AJ. A certain fate: spread of HIV among young injecting drug users in Manipur, north-east India. AIDS Care 2000; 12(4): 497–504. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Ganju D, Ramesh S, Saggurti N. Factors associated with HIV testing among male injecting drug users: findings from a cross-sectional behavioural and biological survey in Manipur and Nagaland, India. Harm reduction journal 2016; 13(1): 21. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Goswami P, Medhi GK, Armstrong G, et al. An assessment of an HIV prevention intervention among People Who Inject Drugs in the states of Manipur and Nagaland, India. International Journal of Drug Policy 2014; 25(5): 853–64. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Hammett TM, Des Jarlais DC, Kling R, et al. Controlling HIV epidemics among injection drug users: Eight years of cross-border HIV prevention interventions in Vietnam and China. PLoS ONE 2012; 7(8): e43141. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Hammett TM, Kling R, Johnston P, et al. Patterns of HIV prevalence and HIV risk behaviors among injection drug users prior to and 24 months following implementation of cross-border HIV prevention interventions in northern Vietnam and southern China. AIDS Educ Prev 2006; 18(2): 97–115. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Handanagic S, Sevic S, Barbaric J, et al. Correlates of anti-hepatitis C positivity and use of harm reduction services among people who inject drugs in two cities in Croatia. Drug and alcohol dependence 2017; 171: 132–9. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Jenkins C, Rahman H, Saidel T, Jana S, Hussain AMZ. Measuring the impact of needle exchange programs among injecting drug users through the National Behavioural Surveillance in Bangladesh. AIDS Education and Prevention 2001; 13(5): 452–61. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Khan AA, Khan A. Performance and coverage of HIV interventions for injection drug users: Insights from triangulation of programme, field and surveillance data from Pakistan. International Journal of Drug Policy 2011; 22(3): 219–25. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Lin P, Fan ZF, Yang F, et al. [Evaluation of a pilot study on needle and syringe exchange program among injecting drug users in a community in Guangdong, China]. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi 2004; 38(5): 305–8. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Nazari SSH, Noroozi M, Soori H, et al. The effect of on-site and outreach-based needle and syringe programs in people who inject drugs in Kermanshah, Iran. International Journal of Drug Policy 2016; 27: 127–31. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Otiashvili D, Gambashidze N, Kapanadze E, Lomidze G, Usharidze D. Effectiveness of needle/syringe exchange program in Tbilisi. Georgian Med News 2006; (140): 62–5. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Power R, Khalfin R, Nozhkina N, Kanarsky I. An evaluation of harm reduction interventions targeting injecting drug users in Sverdlovsk Oblast, Russia. International Journal of Drug Policy 2004; 15(4): 305–10. [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Reynolds A The impact of limited needle and syringe availability programmes on HIV transmission-a case study in Kathmandu. Int J Drug Policy 2000; 11(6): 377–9. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Ruan Y, Liang S, Zhu J, et al. Evaluation of harm reduction programs on seroincidence of HIV, hepatitis B and C, and syphilis among intravenous drug users in southwest China. Sex Transm Dis 2013; 40(4): 323–8. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Samo RN, Altaf A, Memon A, Shah SA. Determinants of HIV sero-conversion among male injection drug users enrolled in a needle exchange programme at Karachi, Pakistan. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association 2013; 63(1): 90–4. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Saukhat SR, Vorontsov DV, Tormozova NM, et al. [The effect of a syringe-exchange program on a decrease in the risk of HIV infection among intravenous narcotic abusers in the city of Rostov-on-Don]. Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol 2000; (4): 89–92. [ PubMed ]

- 39. Sharma M, Panda S, Sharma U, Singh HN, Sharma C, Singh RR. Five years of needle syringe exchange in Manipur, India: programme and contextual issues. International Journal of Drug Policy 2003; 14(5–6): 407–15. [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Strathdee SA, Lozada R, Martinez G, et al. Social and structural factors associated with HIV infection among female sex workers who inject drugs in the Mexico-US border region. PLoS One 2011; 6(4): e19048. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Vassilev ZP, Hagan H, Lyubenova A, et al. Needle exchange use, sexual risk behaviour, and the prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus infections among Bulgarian injection drug users. International Journal of STD and AIDS 2006; 17(9): 621–6. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Wu Q, Kamphuis C, Duo L, Luo J, Chen Y, Richardus JH. Coverage of harm reduction services and HIV infection: a multilevel analysis of five Chinese cities. Harm reduction journal 2017; 14(1): 10. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. Wu Z, Luo W, Sullivan SG, et al. Evaluation of a needle social marketing strategy to control HIV among injecting drug users in China. AIDS 2007; 21 Suppl 8: S115–22. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. Zamani S, Vazirian M, Nassirimanesh B, et al. Needle and syringe sharing practices among injecting drug users in Tehran: a comparison of two neighborhoods, one with and one without a needle and syringe program. AIDS and behavior 2010; 14(4): 885–90. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. Zhang L, Chen X, Zheng J, et al. Ability to access community-based needle-syringe programs and injecting behaviors among drug users: A cross-sectional study in Hunan Province, China. Harm reduction journal 2013; 10(1). [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 46. Zhou JS, Zhang KL, Zhang LL, et al. A quasi-experimental study on a community-based behaviour change programme among injecting drug users in Sichuan, China. Int J STD AIDS 2009; 20(2): 125–9. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 47. Mehrabi Y, Etemad K, Noroozi A, et al. Correlates of injecting paraphernalia sharing among male drug injectors in Kermanshah, Iran: implications for HCV prevention. Journal of Substance Use 2020; 25(3): 330–5. [ Google Scholar ]

- 48. Naserirad M, Beulaygue IC. Accessibility of Needle and Syringe Programs and Injecting and Sharing Risk Behaviors in High Hepatitis C Virus Prevalence Settings. Subst Use Misuse 2020; 55(6): 900–8. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 49. Noroozi M, Marshall BDL, Noroozi A, et al. Do needle and syringe programs reduce risky behaviours among people who inject drugs in Kermanshah City, Iran? A coarsened exact matching approach. Drug Alcohol Rev 2018; 37 Suppl 1: S303–S8. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 50. Noroozi M, Noroozi A, Sharifi H, et al. Needle and Syringe Programs and HIV-Related Risk Behaviors Among Men Who Inject Drugs: A Multilevel Analysis of Two Cities in Iran. International journal of behavioral medicine 2019; 26(1): 50–8. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 51. Sawangjit R, Khan TM, Chaiyakunapruk N. Effectiveness of pharmacy-based needle/syringe exchange programme for people who inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2017; 112(2): 236–47. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 52. Vorobjov S, Uusküla A, Abel-Ollo K, Talu A, Rüütel K, Des Jarlais DC. Comparison of injecting drug users who obtain syringes from pharmacies and syringe exchange programs in Tallinn, Estonia. Harm reduction journal 2009; 6: 3. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 53. Burris S, Welsh J, Ng M, Li M, Ditzler A. State Syringe and Drug Possession Laws Potentially Influencing Safe Syringe Disposal by Injection Drug Users. Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association (1996) 2002; 42(6, Supplement 2): S94–S8. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 54. Golub ET, Bareta JC, Mehta SH, McCall LD, Vlahov D, Strathdee SA. Correlates of Unsafe Syringe Acquisition and Disposal Among Injection Drug Users in Baltimore, Maryland. Substance Use & Misuse 2005; 40(12): 1751–64. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 55. Bluthenthal RN, Anderson R, Flynn NM, Kral AH. Higher syringe coverage is associated with lower odds of HIV risk and does not increase unsafe syringe disposal among syringe exchange program clients. Drug and alcohol dependence 2007; 89(2): 214–22. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 56. El-Bassel N, Strathdee SA. Women who use or inject drugs: an action agenda for women-specific, multilevel and combination HIV prevention and research. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2015; 69(Suppl 2): S182–S90. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 57. Tuchman E Women’s injection drug practices in their own words: a qualitative study. Harm reduction journal 2015; 12(1): 6. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 58. Evans JL, Hahn JA, Page-Shafer K, et al. Gender differences in sexual and injection risk behavior among active young injection drug users in San Francisco (the UFO study). Journal of Urban Health 2003; 80(1): 137–46. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 59. Wechsberg WM, Deren S, Myers B, et al. Gender-specific HIV prevention interventions for women who use alcohol and other drugs: The evolution of the science and future directions. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2015; 69(0 1): S128–S39. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 60. Harm Reduction International. Global State of Harm Reduction 2020 2020. https://www.hri.global/files/2020/10/26/Global_State_HRI_2020_BOOK_FA.pdf (accessed November 17 2020).

- 61. Lancet The. The future of harm reduction programmes in Russia. The Lancet 2009; 374(9697): 1213. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 62. Péter S, Georgieva Y. The Oldest Harm Reduction Organisation in Bulgaria Shut Down 2020. https://drogriporter.hu/en/the-oldest-harm-reduction-organisation-in-bulgaria-shut-down/ (accessed November 17 2020).

- 63. World Health Organization, United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. WHO, UNODC, UNAIDS technical guide for countries to set targets for universal access to HIV prevention, treatment and care for injecting drug users Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- 64. Miller WC, Hoffman IF, Hanscom BS, et al. A scalable, integrated intervention to engage people who inject drugs in HIV care and medication-assisted treatment (HPTN 074): a randomised, controlled phase 3 feasibility and efficacy study. Lancet 2018; 392(10149): 747–59. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 65. Des Jarlais DC, Huong DT, Oanh KTH, et al. Ending an HIV epidemic among persons who inject drugs in a middle-income country: extremely low HIV incidence among persons who inject drugs in Hai Phong, Viet Nam. Aids 2020; 34(15): 2305–11. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

- View on publisher site

- PDF (1.8 MB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 11 April 2017

Effectiveness of needle and syringe Programmes in people who inject drugs – An overview of systematic reviews

- Ricardo M Fernandes 1 , 3 ,

- Maria Cary 2 ,

- Gonçalo Duarte 1 ,

- Gonçalo Jesus 1 ,

- Joana Alarcão 1 ,

- Carla Torre 2 ,

- Suzete Costa 2 ,

- João Costa 1 , 3 &

- António Vaz Carneiro 1 , 3

BMC Public Health volume 17 , Article number: 309 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

28k Accesses

166 Citations

83 Altmetric

Metrics details

Needle and syringe programmes (NSP) are a critical component of harm reduction interventions among people who inject drugs (PWID). Our primary objective was to summarize the evidence on the effectiveness of NSP for PWID in reducing blood-borne infection transmission and injecting risk behaviours (IRB).

We conducted an overview of systematic reviews that included PWID (excluding prisons and consumption rooms), addressed community-based NSP, and provided estimates of the effect regarding incidence/prevalence of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), Hepatitis C virus (HCV), Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and bacteremia/sepsis, and/or measures of IRB. Systematic literature searches were undertaken on relevant databases, including EMBASE, MEDLINE, and PsychINFO (up to May 2015). For each review we identified relevant studies and extracted data on methods, and findings, including risk of bias and quality of evidence assessed by review authors. We evaluated the risk of bias of each systematic review using the ROBIS tool. We categorized reviews by reported outcomes and use of meta-analysis; no additional statistical analysis was performed.

We included thirteen systematic reviews with 133 relevant unique studies published between 1989 and 2012. Reported outcomes related to HIV ( n = 9), HCV ( n = 8) and IRB ( n = 6). Methods used varied at all levels of design and conduct, with four reviews performing meta-analysis. Only two reviews were considered to have low risk of bias using the ROBIS tool, and most included studies were evaluated as having low methodological quality by review authors. We found that NSP was effective in reducing HIV transmission and IRB among PWID, while there were mixed results regarding a reduction of HCV infection. Full harm reduction interventions provided at structural level and in multi-component programmes, as well as high level of coverage, were more beneficial.

Conclusions

The heterogeneity and the overall low quality of evidence highlights the need for future community-level studies of adequate design to support these results.

Trial registration

The protocol of this systematic review was registered in Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO 2015: CRD42015026145 ).

Peer Review reports

People who inject drugs (PWID) experience high levels of morbidity and mortality. Drug-related harms include overdose, drug-related deaths, and blood-borne infections such as Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), Hepatitis C (HCV), Hepatitis B (HBV), and bacteremia/sepsis. HCV is currently the most prevalent infectious disease affecting PWID, while HIV prevalence rates are lower. In an estimated total of 12.7 to 16 million PWID worldwide, it is believed that 1.2 million are infected with HIV [ 1 ] and 10 million are infected with HCV [ 2 ]. Sharing needles and syringes, as well as other injecting paraphernalia, is a key route of transmission of these infections [ 3 ].

Needle and syringe programmes (NSP) are thought to be a critical component of harm reduction interventions among PWID [ 3 , 4 ]. The first NSP was established in the 1980s [ 5 ], in response to the global HIV epidemic, with the goal of providing access and encouraging the use of sterile injection paraphernalia by PWID. Since then, provision of these services has grown rapidly. Importantly, a shift in paradigm has favoured NSP as components of harm reduction or harm minimization policies, which focus on reducing all drug-related harms, i.e. preventing HIV, HBV and HCV infection, minimizing needle and syringe sharing and reuse, reducing the volume of discarded needles and syringes in the environment, and facilitating access to sterile paraphernalia. Furthermore, NSP may also promote the use of condoms and provide opportunistic relevant health information and services [ 3 ].

NSP are complex health interventions with several interacting components, such as behavioural changes in PWID and providers, a complex operating framework (users, providers, setting, health systems), and some degree of flexibility of interventions [ 6 ]. There is considerable variability among regions and countries in service provision, coverage and range of harm reduction interventions offered by NSP. In particular, a variety of measures have been developed to improve access to and use of sterile injecting equipment and to increase users’ choice. These include several methods of distribution or sale such as conventional NSP in fixed-sites, pharmacy-based distribution, dispensing machines and outreach programmes – often using a mobile van or bus, or through home-visits [ 3 ]. Generally, pharmacy and specialist needle exchange provides a wide range of harm reduction information and advice, along with clean needles and syringes and possibly injecting paraphernalia. The legal framework in which NSP operate also varies at country level [ 7 ]. Pharmacy-based NSP are known to be in place in at least Australia [ 8 ], Belgium, France, Ireland, Kyrgyzstan, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Slovenia, Ukraine [ 7 , 9 ], UK [ 10 ], and New Zealand [ 11 ].

Many systematic reviews on the effectiveness of interventions providing injecting equipment have been conducted to date. Overviews of reviews which compile information from these multiple systematic reviews, have also been published. The aim of these overviews is to provide end-users with a comprehensive and critical summary of the available evidence on this intervention. Overviews are of particular interest in this field because existing systematic reviews have focused on disparate questions, regarding either specific populations (e.g. country-specific evidence), specific types of interventions (e.g. different types of NSP provision) or, most commonly, specific outcomes (e.g. HIV or HCV transmission) [ 12 – 14 ]. Furthermore, there is variability in methods used in these systematic reviews, including the assessment of possible biases and the use of quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis). Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, the published overviews in this field have focused only on specific outcomes, i.e. transmission of HIV and/or HCV.

Our primary objective was to conduct an overview of systematic reviews that evaluated the evidence of the effectiveness of NSP for PWID across a range of different relevant outcomes, i.e. blood-borne infection transmission and injecting risk behaviours (IRB).

Our secondary objective was to assess how different aspects of NSP provision, including provider, setting, coverage and any related component delivered in parallel, such as harm reduction services and opiate substitution therapy, modified the effect of NSP, with a particular focus on pharmacy-driven NSP.

We followed current guidance on the conduct of overviews of reviews, including recommendations from the Cochrane Collaboration [ 15 ] and guidance on public health intervention reviews by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination of the University of York [ 16 ]. We also followed the recommendations from the PRISMA-P statement regarding reporting items that we considered applicable to this overview [ 17 ]. The protocol for this overview was registered at PROSPERO (CRD42015026145) available at http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42015026145 .

Eligibility criteria

For inclusion in this overview, studies had to meet the following criteria:

Study design: systematic reviews, operationally defined as studies reporting a clearly stated set of objectives, eligibility criteria, a systematic search using two or more sources, a systematic presentation of the characteristics and findings of the included studies, and estimates of the size and direction of the effect of interventions presented as numerical data, on an individual study-level basis and/or with quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis);

Participants: PWID, defined as people who inject some form of drug at the beginning of the study. We excluded studies focusing exclusively on participants whose consumption was confined to prisons and consumption rooms, since these are populations with distinct characteristics from our target population;

Interventions: systematic reviews had to evaluate community-based NSP, defined as the supply of at least needles and syringes, with or without other injecting paraphernalia for the preparation and consumption of drugs;

Outcomes: required reported outcomes included the incidence and/or prevalence of blood-borne infections (HIV, HCV, HBV and bacteremia/sepsis), and/or measures of IRB (including but not limited to syringe re-use, borrowing, sharing, renting and lending).

When more than one review included exactly the same studies, the review that reported the most complete presentation of results was selected for inclusion in the overview.

Search strategy and screening

Searches were undertaken on MEDLINE®In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations (from 1946 to 12th of May 2015), EMBASE (from 1974 to 12th of May 2015) and PsycINFO (from 1806 to 12th of May 2015) via the OVID SP interface. In addition, the following databases were searched: the NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED), the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), the Campbell Library of Systematic Reviews and the Database of Promoting Health Effectiveness Reviews (DoPHER). The search strategies for each database are shown in a supplementary file (Additional file 1 ). No language or other types of restrictions were applied. In addition to the database searches, handsearching of the references of the included reviews was undertaken to identify further relevant studies.

Titles and abstracts of articles identified were screened independently by two authors (MC, JA), and classified as include, unclear or exclude. The full reports of all articles that classified as include or unclear were then obtained, and two authors (MC, GD) examined compliance of reviews with eligibility criteria, with a third author acting as an arbiter (RF).

Data extraction

Data from reports of all included systematic reviews were extracted by two authors (MC, GD) and validated by a third author (RF), using a data extraction form designed and pre-piloted for this overview. The following general characteristics were extracted from each systematic review: publication details; study objectives; eligibility criteria (population, intervention, comparators, outcomes, study designs); any reported protocol; and methods used for search, screening, data extraction and synthesis. For each systematic review, we listed all included studies and evaluated whether they matched the eligibility criteria for this overview regarding population, interventions and outcomes. We then extracted the following results from the eligible group of studies, whenever reported at the systematic review level: study design; countries involved; characteristics of included participants (demographics, prevalence of HIV/HCV); description of interventions and any co-intervention, duration of intervention and follow-up; effect estimates from meta-analysis (if available) or at individual study-level, for each relevant outcome; and any subgroup or sensitivity analyses. The authors’ conclusions for each relevant outcome were also collected. We contacted the authors of reviews for relevant missing data.

Assessment of methodological quality

At a study level, we extracted data on any risk of bias assessments of primary studies when performed and reported by reviewers in each systematic review, including tools used and summarized results. We also collected data on any reported evaluations of the quality of evidence concerning our outcomes of interest in included reviews, particularly those using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) tool [ 18 ], as well as data on assessments of publication bias.

At a systematic review level, we assessed the methodological quality of each included systematic review using the Risk Of Bias In Systematic Reviews (ROBIS) tool [ 19 ]. Two review authors (MC, RF) performed quality assessments independently, using piloted decision rules. Disagreements regarding overall assessments were resolved through discussion, with a third reviewer serving as the final arbitrator (AVC). The rationale behind assessments was documented. We calculated measures of agreement and reliability between raters for each ROBIS domain.

Data synthesis

We stratified the included systematic reviews by: (i) type of outcomes assessed (blood-borne infections, IRB), and (ii) type of analysis (with or without meta-analysis). We summarized data from the included reviews both in text and in summary tables and figures. When meta-analysis was performed, we report pooled estimates using the models and measures of effect reported by systematic review authors, with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI); we did not perform any additional statistical analysis. When reported, the accompanying I 2 values, which describe the percentage of total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance, were collected [ 20 ].

The search and screening process is summarised in Fig. 1 . A total of 667 citations were identified through the various database searches. Three additional records were identified in the reference lists of screened studies. After 37 duplicates were removed, we obtained 633 citations, which were screened by title and abstract. We excluded 582 citations as they did not meet the inclusion criteria, and the remaining 51 were screened full text. Thirty-five citations were further excluded, and two reports [ 21 , 22 ] were unobtainable. Fourteen reports were thus included, corresponding to 13 systematic reviews, as two records referred to the same study [ 12 , 23 ]. Within those publications three were reports from National Institutes/Expert Commitees in the US [ 24 ], UK [ 12 ] and Canada [ 25 ], while 10 were regular papers published in scientific journals.

Screening decisions up to date as of 30Jun2015. Original search date 12May2015

Description of included reviews

Table 1 lists the key characteristics of the 13 included systematic reviews that evaluated the evidence of the effectiveness of NSP for PWID in the community setting. We classified reviews by type of outcomes reported and type of data analysis (Fig. 2 ).

Studies selected for inclusion classified by outcome(s) reported and strategy for data synthesis. *Grey shaded boxes represent the outcome reported in the reviews indicated in the right column. “HIV”, ”HCV” and “Injecting risk behaviours” is used to classify the reviews that reported the impact of NSP in the number of HIV infections, number of HCV infections and change in injection behavior. The reviews are also presented in the right column by strategy used for data synthesis