Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

2 – Critical Reading

“Citizens of modern societies must be good readers to be successful. Reading skills do not guarantee success for anyone, but success is much harder to come by without being a skilled reader. The advent of the computer and the Internet does nothing to change this fact about reading. If anything, electronic communication only increases the need for effective reading skills and strategies as we try to cope with the large quantities of information made available to us.” –William Grabe

The importance of reading as a literacy skill is without a doubt. It is essential for daily life navigation and academic success. Reading for daily life navigation is relatively easier, compared to academic reading. Think about the kinds of reading you did in elementary and high school (e.g., story books, picture books, textbook chapters, literary works, online information, lecture notes, etc.).

Now think about what you were expected to do with your reading at school (e.g., memorize, summarize, discuss, pass a test, apply information, or write essays or papers).

Research shows that what you expect to do with a text affects how you read it.

–Bartholomae & Petrosky (1996)

So, reading is not always the same; you read school texts differently than the texts you choose outside of school tasks. Furthermore, there are many external and internal factors that influence how you interpret and use what you read. Much depends on your background (e.g., cultural participation in communities, identity, historical knowledge), and the context in which you are reading. Classrooms and teachers certainly have an influence. The teaching methods used by your instructor, the texts your instructor chooses, and expectations of student performance on assignments all affect how you read and what you do to accomplish an assignment.

Different levels of education also emphasize different types of reading. For example, in primary or secondary education, you learn what is known, so you focus on correctness, memorization of facts, and application of facts. In higher education, although you might still be required to understand and memorize information, you expand what is known by examining ideas and creating new knowledge. In those processes at different levels, reading has been used for different purposes.

Multilingual reading and writing expert William Grabe has identified six different purposes:

- Reading to search for information (scanning and skimming)

- Reading for quick understanding (skimming)

- Reading to learn

- Reading to integrate information

- Reading to evaluate, critique, and use information

- Reading for general comprehension (in many cases, reading for interest or reading to entertain)

In college, reading to evaluate, critique, and use information is the most practiced and tested skill. But what does it mean? Reading to evaluate, critique, and use information is related to critical reading.

Definition of Critical Reading

Critical reading is a more ACTIVE way of reading. It is a deeper and more complex engagement with a text. Critical reading is a process of analyzing, interpreting and, sometimes, evaluating. When we read critically, we use our critical thinking skills to QUESTION both the text and our own reading of it. Different disciplines may have distinctive modes of critical reading (scientific, philosophical, literary, etc).

[Source: Duncan , n.d., Critical Reading ]

Critical reading does not have to be all negative. The aim of critical reading is not to find fault but to assess the strength of the evidence and the argument. It is just as useful to conclude that a study, or an article, presents very strong evidence and a well-reasoned argument, as it is to identify the studies or articles that are weak.

[Source: What is critical reading? ]

There’s No Reason to Eat Animals by Lindsay Rajt

If we care about the environment and believe that kindness is a virtue-as we all say that we do–a vegan diet is the only sensible option. The question becomes: Why eat animals at all?

Animals are made of flesh, bone, and blood, just as you and I are. They form friendships, feel pain and joy, grieve for lost loved ones and are afraid to die. One cannot profess to care about animals while tearing them away from their friends and families and cutting their throats–or paying someone else to do it–simply to satisfy a fleeting taste for flesh.

[adapted from Pattison, 2015, Critical Reading: English for Academic Purposes for instructional purposes ]

What is your position on the issue?

Do you think that the language used helps the audience? How?

How does the language use affect your evaluation of the issue?

Obesity: A Public Health Failure? By Tavis Glassman PhD, MPH, MCHES, Jennifer Glassman M.A., CCC-SLP, and Aaron J. Diehr, M.A.

Obesity rates continue to increase, bringing into question the efficacy of prevention and treatment efforts. While intuitively appealing, the law on weight gain focusing on calories is too simplistic because calories represent only one factor on issues of weight management. From a historical perspective, the recommendation to eat a low fat, high carbohydrate diet may have been the wrong message to promote, thereby making the obesity situation worse. Suggestions to solve the issues of obesity include taxing, restricting advertising, and reducing the use of sugar. Communities must employ these and other strategies to decrease sugar use and reduce obesity rates.

How would you describe the authors’ educational background?

How does the authors’ background affect your evaluation of the argument?

Students Want More Mobile Devices in Classroom by Ellis Booker

Released last week, the Student Mobile Device Survey reveals that students almost unanimously believe mobile technology will change education and make learning more fun. The survey, which collected the responses of 2,350 US students, was conducted for learning company Pearson by Harris Interactive.

According to the survey, 92% of elementary, middle and high school students believe mobile devices will change the way students learn in the future and make learning more fun (90%). A majority (69%) would like to use mobile devices more in the classroom.

The survey results also contained some surprises. For example, college students in math and science are much more likely to use technology for learning, and researchers expected to see this same pattern in the lower grades.

Are you convinced by the survey results? Why?

Color Scheme Associations in Context

The colors you surround yourself with at work are also important as they make a difference in how you are perceived by members of the public. Traditional workplaces still use dark colors such as navy blue, forest green, and chocolate brown to give clients a sense of seriousness and professionalism.

Think about it: which accountant would you choose to prepare your tax return: the one whose office has navy blue drapes and lamps and a maritime scene on the wall or the one whose office is painted in hot pink with a cartoon character on the wall? An online survey of lawyers carried out by Legal Scene magazine showed that of 287 respondents, 38 percent chose a navy blue color scheme for their office; 32 percent chose brown; 19 percent chose forest green; 7 percent chose burgundy; and only 4 percent chose red, pink or orange (Perkins, 2013).

What kind of bias might be implicated in this survey?

What is your personal experience?

These practices do not ask you to memorize or summarize the information you read, but instead, they ask you to provide your opinions and judgment. To answer those questions, you need to engage in critical reading, a form of active reading.

Active reading, which predominates college-level reading, means reading with the purpose of getting a deeper understanding of the texts you are reading and being engaged in the actions of analyzing, questioning, and evaluating the texts. In other words, instead of accepting the information given to you, you challenge its value by examining the source of the information and the formation of an argument.

The difference in how you read falls into two broad categories:

(Source: Reading Critically ]

Reading critically and actively is essential for college students. But what does critical reading look like in actual practice? Here are the steps that you can follow to do the critical reading.

Step 1: Understand the purpose of your reading and be selective

As college students, you are very busy with your daily coursework. A freshman usually takes four to five courses or even six courses per semester. This means you have tons of reading to do every week. Getting to know the purpose of the reading assignments can save you time as your reading is more targeted. Remember you do not have to read a whole chapter or book. What you can do is through scanning to determine the sections that are useful for you and then read the parts carefully.

Step 2: Evaluate the reading text

While reading a text, you need to question/analyze/evaluate the text by considering the following:

- Assess whether a source is reliable (Read around the text for the title, author, publisher, publication date, good/bad examples, tones, etc.)

- Distinguish between facts and opinions (Scan for any evidence)

- Recognize multiple opinions in a text

- Infer meaning when it is not directly stated

- Agree or disagree with what you read

- Consider the relevance of the text to your task

- Consider what is missing from a text

It may well be necessary to read passages several times to gain a full understanding of texts and be able to evaluate the source. In this process, you can underline, highlight, or circle important parts and points, take notes, or add comments in the margins.

Critical reading often involves re-reading a text multiple times, putting our focus on different aspects of the text. The first time we read a text, we may be focused on getting an overall sense of the information the author is presenting – in other words, simply understanding what they are trying to say. On subsequent readings, however, we can focus on how the author presents that information, the kinds of evidence they provide to support their arguments (and how convincing we find that evidence), the connection between their evidence and their conclusions, etc.

[Source: Lane, 2021, Critical Thinking for Critical Writing ]

Step 3: Document your reading and form your own argument

After you finish reading a text, sort out your notes and keep track of the sources you have read on the topic you are exploring. After you read several sources, you might be able to form your own argument(s) and use the sources as evidence for your argument(s).

In college, critical reading usually leads to critical writing.

Critical writing comes from critical reading. Whenever you have to write a paper, you have to reflect on various written texts, think and interpret research that has previously been carried out on your subject. With the aim of writing your independent analysis of the subject, you have to critically read sources and use them suitably to formulate your argument. The interpretations and conclusions you derive from the literature you read are the stepping stones towards devising your own approach.

[Source: Does Critical Reading Influence Academic Writing? ]

In a word, through critical reading, you form your own argument(s), and the evidence used to support your argument(s) is usually from the texts that you read critically. The Source Essay Writing Service explains how critical reading influences academic writing.

How does critical reading influence your writing skills?

Once you start reading texts critically, you develop an understanding of how to write research papers. Here are some practical tips that will help you in academic writing:

- Examine introductions and conclusions of the texts while critical reading so when you write an independent content, you would be able to decide how to focus your critical work.

- When you highlight or take notes from a text, make sure you focus on the argument. The way the author explains the analytical progress, the concepts used, and arriving at conclusions will help you to write your own facts and examples in an interesting way.

- By closely reading the texts, you will be able to look for the patterns that give meaning, purpose, and consistency to the text. The way the arguments are presented in paragraphs will aid you in structuring information in your writing.

- When you critically read a text, you are able to learn how an argument is placed in the text. Try to understand how you can use this placement strategy in academic writing. Paying attention to the context is an important aspect that you learn from critical reading.

- While reading a text, you will notice that the author has given the due credit to the sources used or the references that were consulted. This will help you in understanding how you can cite sources and quotes in your content.

- Critical reading skills enhance your way of thinking and writing skills. The more you read, the better is your knowledge and vocabulary. It is important to use the precise words to express your meaning. You can learn new words and improve your writing by reading as many texts as you can.

Activity 1: Discuss the following questions with your group

- A website from the United Nations Educational, Scientific ad Cultural Organization (UNESCO) gives some statistics about the level of education reached by young women in Indonesia. Is this a reliable source?

- You find an interesting article about addiction to online gambling. The article has some interesting statistics, but it was published ten years ago. Is it worth using?

- You find a book about World War II that presents a different opinion from your other sources. What would you like to know about the author before you decide whether or not to take him seriously?

- An article tells you that research into space exploration is a waste of money. Do you think this article is presenting facts or opinions? How can you tell? What might you look for in the article?

- You find some research that states that people who own dogs generally live longer lives than those who do not. The author has some convincing arguments, but you are not sure whether or not she has enough evidence. How mush is enough?

- A newspaper article tells you about human rights abuses in a certain country. The writer of this article has never visited the country in question; his claims are based on interviews with other people. How would you evaluate his information?

- You find two websites about the use of seaweed as a source of energy. One is full of long words and complicated sentences; the other uses simple, clear language. Is the first one a more reliable source?

- You have read nine different articles that tell you that there is no connection between wealth and happiness. The tenth article gives the opposite opinion: rich people are happier than those who are poor. What questions would you ask yourself about this article before you decide whether or not to consider it?

Activity 2: Reading for analyzing styles

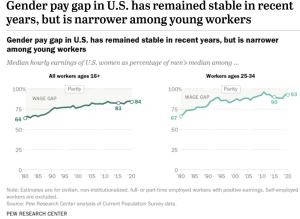

Please read the news and discuss the importance of the graphs in supporting the arguments of the text.

Gender Pay Gap in U.S. Held Steady in 2020

By amanda barroso and anna brown.

The gender gap in pay has remained relatively stable in the United States over the past 15 years or so. In 2020, women earned 84% of what men earned, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of median hourly earnings of both full- and part-time workers. Based on this estimate, it would take an extra 42 days of work for women to earn what men did in 2020.

As has been the case in recent decades, the 2020 wage gap was smaller for workers ages 25 to 34 than for all workers 16 and older. Women ages 25 to 34 earned 93 cents for every dollar a man in the same age group earned on average. In 1980, women ages 25 to 34 earned 33 cents less than their male counterparts, compared with 7 cents in 2020. The estimated 16-cent gender pay gap among all workers in 2020 was down from 36 cents in 1980.

The U.S. Census Bureau has also analyzed the gender pay gap, though its analysis looks only at full-time workers (as opposed to full- and part-time workers). In 2019, full-time, year-round working women earned 82% of what their male counterparts earned, according to the Census Bureau’s most recent analysis.

Why does a gender pay gap still persist?

Much of this gap has been explained by measurable factors such as educational attainment, occupational segregation and work experience. The narrowing of the gap is attributable in large part to gains women have made in each of these dimensions.

Even though women have increased their presence in higher-paying jobs traditionally dominated by men, such as professional and managerial positions, women as a whole continue to be over-represented in lower-paying occupations relative to their share of the workforce. This may contribute to gender differences in pay.

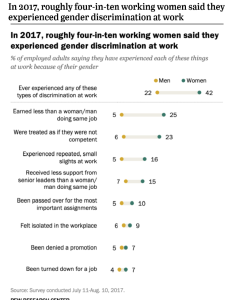

Other factors that are difficult to measure, including gender discrimination, may also contribute to the ongoing wage discrepancy. In a 2017 Pew Research Center survey , about four-in-ten working women (42%) said they had experienced gender discrimination at work, compared with about two-in-ten men (22%). One of the most commonly reported forms of discrimination focused on earnings inequality. One-in-four employed women said they had earned less than a man who was doing the same job; just 5% of men said they had earned less than a woman doing the same job.

Motherhood can also lead to interruptions in women’s career paths and have an impact on long-term earnings. Our 2016 survey of workers who had taken parental, family or medical leave in the two years prior to the survey found that mothers typically take more time off than fathers after birth or adoption. The median length of leave among mothers after the birth or adoption of their child was 11 weeks, compared with one week for fathers. About half (47%) of mothers who took time off from work in the two years after birth or adoption took off 12 weeks or more.

Mothers were also nearly twice as likely as fathers to say taking time off had a negative impact on their job or career. Among those who took leave from work in the two years following the birth or adoption of their child, 25% of women said this had a negative impact at work, compared with 13% of men.

[Source: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/05/25/gender-pay-gap-facts/ ]

Activity 3: Reading for arguments

What’s the main argument of the poem?

Fire and Ice

By robert frost, some say the world will end in fire, some say in ice. from what i’ve tasted of desire i hold with those who favor fire. but if it had to perish twice, i think i know enough of hate to say that for destruction ice is also great and would suffice..

References:

Barroso, A., & Brown, A. (2021, May 25). Gender pay gap in U.S. held steady in 2020. Pew Research Center. Retrieved July 22, 2022, from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/05/25/gender-pay-gap-facts/

Bartholomae, D., Petrosky, T., & Waite, S. (2002). Ways of reading: An anthology for writers (p. 720). Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Duncan, J. (n.d.). The Writing Centre, University of Toronto Scarborough. Modified by Michael O’Connor. https://www.stetson.edu/other/writing-program/media/CRITICAL%20READING.pdf

Grabe, W. (2008). Reading in a second language: Moving from theory to practice. Cambridge University Press.

Lane, J. (2021, July 9). Critical thinking for critical writing. Simon Fraser University. Retrieved July 22, 2022, from https://www.lib.sfu.ca/about/branches-depts/slc/writing/argumentation/critical-thinking-writing

Pattison, T. (2015). Critical Reading: English for academic purposes for instructional purposes. Pearson.

Sourceessay. (n.d.). What is critical reading. https://sourceessay.com/does-critical-reading-influence-academic-writing/

University of Leicester. (n.d.). What is critical reading? Bangor University. https://www.bangor.ac.uk/studyskills/study-guides/critical-reading.php.en

Critical Reading, Writing, and Thinking Copyright © 2022 by Zhenjie Weng, Josh Burlile, Karen Macbeth is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- LEARNING SKILLS

- Study Skills

- Critical Reading

Search SkillsYouNeed:

Learning Skills:

- A - Z List of Learning Skills

- What is Learning?

- Learning Approaches

- Learning Styles

- 8 Types of Learning Styles

- Understanding Your Preferences to Aid Learning

- Lifelong Learning

- Decisions to Make Before Applying to University

- Top Tips for Surviving Student Life

- Living Online: Education and Learning

- 8 Ways to Embrace Technology-Based Learning Approaches

- Critical Thinking Skills

- Critical Thinking and Fake News

- Understanding and Addressing Conspiracy Theories

- Critical Analysis

- Top Tips for Study

- Staying Motivated When Studying

- Student Budgeting and Economic Skills

- Getting Organised for Study

- Finding Time to Study

- Sources of Information

- Assessing Internet Information

- Using Apps to Support Study

- What is Theory?

- Styles of Writing

- Effective Reading

- Note-Taking from Reading

- Note-Taking for Verbal Exchanges

- Planning an Essay

- How to Write an Essay

- The Do’s and Don’ts of Essay Writing

- How to Write a Report

- Academic Referencing

- Assignment Finishing Touches

- Reflecting on Marked Work

- 6 Skills You Learn in School That You Use in Real Life

- Top 10 Tips on How to Study While Working

- Exam Skills

Get the SkillsYouNeed Study Skills eBook

Part of the Skills You Need Guide for Students .

- Writing a Dissertation or Thesis

- Research Methods

- Teaching, Coaching, Mentoring and Counselling

- Employability Skills for Graduates

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter and start improving your life in just 5 minutes a day.

You'll get our 5 free 'One Minute Life Skills' and our weekly newsletter.

We'll never share your email address and you can unsubscribe at any time.

Critical Reading and Reading Strategy

What is critical reading.

Reading critically does not, necessarily, mean being critical of what you read.

Both reading and thinking critically don’t mean being ‘ critical ’ about some idea, argument, or piece of writing - claiming that it is somehow faulty or flawed.

Critical reading means engaging in what you read by asking yourself questions such as, ‘ what is the author trying to say? ’ or ‘ what is the main argument being presented? ’

Critical reading involves presenting a reasoned argument that evaluates and analyses what you have read. Being critical, therefore - in an academic sense - means advancing your understanding , not dismissing and therefore closing off learning.

See also: Listening Types to learn about the importance of critical listening skills.

To read critically is to exercise your judgement about what you are reading – that is, not taking anything you read at face value.

When reading academic material you will be faced with the author’s interpretation and opinion. Different authors will, naturally, have different slants. You should always examine what you are reading critically and look for limitations, omissions, inconsistencies, oversights and arguments against what you are reading.

In academic circles, whilst you are a student, you will be expected to understand different viewpoints and make your own judgements based on what you have read.

Critical reading goes further than just being satisfied with what a text says, it also involves reflecting on what the text describes, and analysing what the text actually means, in the context of your studies.

As a critical reader you should reflect on:

- What the text says: after critically reading a piece you should be able to take notes, paraphrasing - in your own words - the key points.

- What the text describes: you should be confident that you have understood the text sufficiently to be able to use your own examples and compare and contrast with other writing on the subject in hand.

- Interpretation of the text: this means that you should be able to fully analyse the text and state a meaning for the text as a whole.

Critical reading means being able to reflect on what a text says, what it describes and what it means by scrutinising the style and structure of the writing, the language used as well as the content.

Critical Thinking is an Extension of Critical Reading

Thinking critically, in the academic sense, involves being open-minded - using judgement and discipline to process what you are learning about without letting your personal bias or opinion detract from the arguments.

Critical thinking involves being rational and aware of your own feelings on the subject – being able to reorganise your thoughts, prior knowledge and understanding to accommodate new ideas or viewpoints.

Critical reading and critical thinking are therefore the very foundations of true learning and personal development.

See our page: Critical Thinking for more.

Developing a Reading Strategy

You will, in formal learning situations, be required to read and critically think about a lot of information from different sources.

It is important therefore, that you not only learn to read critically but also efficiently.

The first step to efficient reading is to become selective.

If you cannot read all of the books on a recommended reading list, you need to find a way of selecting the best texts for you. To start with, you need to know what you are looking for. You can then examine the contents page and/or index of a book or journal to ascertain whether a chapter or article is worth pursuing further.

Once you have selected a suitable piece the next step is to speed-read.

Speed reading is also often referred to as skim-reading or scanning. Once you have identified a relevant piece of text, like a chapter in a book, you should scan the first few sentences of each paragraph to gain an overall impression of subject areas it covers. Scan-reading essentially means that you know what you are looking for, you identify the chapters or sections most relevant to you and ignore the rest.

When you speed-read you are not aiming to gain a full understanding of the arguments or topics raised in the text. It is simply a way of determining what the text is about.

When you find a relevant or interesting section you will need to slow your reading speed dramatically, allowing you to gain a more in-depth understanding of the arguments raised. Even when you slow your reading down it may well be necessary to read passages several times to gain a full understanding.

See also: Speed-Reading for Professionals .

Following SQ3R

SQ3R is a well-known strategy for reading. SQ3R can be applied to a whole range of reading purposes as it is flexible and takes into account the need to change reading speeds.

SQ3R is an acronym and stands for:

This relates to speed-reading, scanning and skimming the text. At this initial stage you will be attempting to gain the general gist of the material in question.

It is important that, before you begin to read, you have a question or set of questions that will guide you - why am I reading this? When you have a purpose to your reading you want to learn and retain certain information. Having questions changes reading from a passive to an active pursuit. Examples of possible questions include:

- What do I already know about this subject?

- How does this chapter relate to the assignment question?

- How can I relate what I read to my own experiences?

Now you will be ready for the main activity of reading. This involves careful consideration of the meaning of what the author is trying to convey and involves being critical as well as active.

Regardless of how interesting an article or chapter is, unless you make a concerted effort to recall what you have just read, you will forget a lot of the important points. Recalling from time to time allows you to focus upon the main points – which in turn aids concentration. Recalling gives you the chance to think about and assimilate what you have just read, keeping you active. A significant element in being active is to write down, in your own words, the key points.

The final step is to review the material that you have recalled in your notes. Did you understand the main principles of the argument? Did you identify all the main points? Are there any gaps? Do not take for granted that you have recalled everything you need correctly – review the text again to make sure and clarify.

Continue to: Effective Reading Critical Thinking

See also: Critical Analysis Writing a Dissertation Critical Thinking and Fake News

IMAGES

VIDEO