- Make an Appointment

- SAGE – STEM Learning Communities

- MINT – Peer Tutoring

- Study Connect

- Request Workshop

How to read and understand a scientific paper

How to read and understand a scientific paper: a guide for non-scientists, london school of economics and political science, jennifer raff.

From vaccinations to climate change, getting science wrong has very real consequences. But journal articles, a primary way science is communicated in academia, are a different format to newspaper articles or blogs and require a level of skill and undoubtedly a greater amount of patience. Here Jennifer Raff has prepared a helpful guide for non-scientists on how to read a scientific paper. These steps and tips will be useful to anyone interested in the presentation of scientific findings and raise important points for scientists to consider with their own writing practice.

My post, The truth about vaccinations: Your physician knows more than the University of Google sparked a very lively discussion, with comments from several people trying to persuade me (and the other readers) that their paper disproved everything that I’d been saying. While I encourage you to go read the comments and contribute your own, here I want to focus on the much larger issue that this debate raised: what constitutes scientific authority?

It’s not just a fun academic problem. Getting the science wrong has very real consequences. For example, when a community doesn’t vaccinate children because they’re afraid of “toxins” and think that prayer (or diet, exercise, and “clean living”) is enough to prevent infection, outbreaks happen.

“Be skeptical. But when you get proof, accept proof.” –Michael Specter

What constitutes enough proof? Obviously everyone has a different answer to that question. But to form a truly educated opinion on a scientific subject, you need to become familiar with current research in that field. And to do that, you have to read the “primary research literature” (often just called “the literature”). You might have tried to read scientific papers before and been frustrated by the dense, stilted writing and the unfamiliar jargon. I remember feeling this way! Reading and understanding research papers is a skill which every single doctor and scientist has had to learn during graduate school. You can learn it too, but like any skill it takes patience and practice.

I want to help people become more scientifically literate, so I wrote this guide for how a layperson can approach reading and understanding a scientific research paper. It’s appropriate for someone who has no background whatsoever in science or medicine, and based on the assumption that he or she is doing this for the purpose of getting a basic understanding of a paper and deciding whether or not it’s a reputable study.

The type of scientific paper I’m discussing here is referred to as a primary research article . It’s a peer-reviewed report of new research on a specific question (or questions). Another useful type of publication is a review article . Review articles are also peer-reviewed, and don’t present new information, but summarize multiple primary research articles, to give a sense of the consensus, debates, and unanswered questions within a field. (I’m not going to say much more about them here, but be cautious about which review articles you read. Remember that they are only a snapshot of the research at the time they are published. A review article on, say, genome-wide association studies from 2001 is not going to be very informative in 2013. So much research has been done in the intervening years that the field has changed considerably).

Before you begin: some general advice

Reading a scientific paper is a completely different process than reading an article about science in a blog or newspaper. Not only do you read the sections in a different order than they’re presented, but you also have to take notes, read it multiple times, and probably go look up other papers for some of the details. Reading a single paper may take you a very long time at first. Be patient with yourself. The process will go much faster as you gain experience.

Most primary research papers will be divided into the following sections: Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results, and Conclusions/Interpretations/Discussion. The order will depend on which journal it’s published in. Some journals have additional files (called Supplementary Online Information) which contain important details of the research, but are published online instead of in the article itself (make sure you don’t skip these files).

Before you begin reading, take note of the authors and their institutional affiliations. Some institutions (e.g. University of Texas) are well-respected; others (e.g. the Discovery Institute ) may appear to be legitimate research institutions but are actually agenda-driven. Tip: g oogle “Discovery Institute” to see why you don’t want to use it as a scientific authority on evolutionary theory.

Also take note of the journal in which it’s published. Reputable (biomedical) journals will be indexed by Pubmed . [EDIT: Several people have reminded me that non-biomedical journals won’t be on Pubmed, and they’re absolutely correct! (thanks for catching that, I apologize for being sloppy here). Check out Web of Science for a more complete index of science journals. And please feel free to share other resources in the comments!] Beware of questionable journals .

As you read, write down every single word that you don’t understand. You’re going to have to look them all up (yes, every one. I know it’s a total pain. But you won’t understand the paper if you don’t understand the vocabulary. Scientific words have extremely precise meanings).

Step-by-step instructions for reading a primary research article

1. Begin by reading the introduction, not the abstract.

The abstract is that dense first paragraph at the very beginning of a paper. In fact, that’s often the only part of a paper that many non-scientists read when they’re trying to build a scientific argument. (This is a terrible practice—don’t do it.). When I’m choosing papers to read, I decide what’s relevant to my interests based on a combination of the title and abstract. But when I’ve got a collection of papers assembled for deep reading, I always read the abstract last. I do this because abstracts contain a succinct summary of the entire paper, and I’m concerned about inadvertently becoming biased by the authors’ interpretation of the results.

2. Identify the BIG QUESTION.

Not “What is this paper about”, but “What problem is this entire field trying to solve?”

This helps you focus on why this research is being done. Look closely for evidence of agenda-motivated research.

3. Summarize the background in five sentences or less.

Here are some questions to guide you:

What work has been done before in this field to answer the BIG QUESTION? What are the limitations of that work? What, according to the authors, needs to be done next?

The five sentences part is a little arbitrary, but it forces you to be concise and really think about the context of this research. You need to be able to explain why this research has been done in order to understand it.

4. Identify the SPECIFIC QUESTION(S)

What exactly are the authors trying to answer with their research? There may be multiple questions, or just one. Write them down. If it’s the kind of research that tests one or more null hypotheses, identify it/them.

Not sure what a null hypothesis is? Go read this one and try to identify the null hypotheses in it. Keep in mind that not every paper will test a null hypothesis.

5. Identify the approach

What are the authors going to do to answer the SPECIFIC QUESTION(S)?

6. Now read the methods section. Draw a diagram for each experiment, showing exactly what the authors did.

I mean literally draw it. Include as much detail as you need to fully understand the work. As an example, here is what I drew to sort out the methods for a paper I read today ( Battaglia et al. 2013: “The first peopling of South America: New evidence from Y-chromosome haplogroup Q” ). This is much less detail than you’d probably need, because it’s a paper in my specialty and I use these methods all the time. But if you were reading this, and didn’t happen to know what “process data with reduced-median method using Network” means, you’d need to look that up.

Image credit: author

You don’t need to understand the methods in enough detail to replicate the experiment—that’s something reviewers have to do—but you’re not ready to move on to the results until you can explain the basics of the methods to someone else.

7. Read the results section. Write one or more paragraphs to summarize the results for each experiment, each figure, and each table. Don’t yet try to decide what the results mean , just write down what they are.

You’ll find that, particularly in good papers, the majority of the results are summarized in the figures and tables. Pay careful attention to them! You may also need to go to the Supplementary Online Information file to find some of the results.

It is at this point where difficulties can arise if statistical tests are employed in the paper and you don’t have enough of a background to understand them. I can’t teach you stats in this post, but here , and here are some basic resources to help you. I STRONGLY advise you to become familiar with them.

Things to pay attention to in the results section:

- Any time the words “significant” or “non-significant” are used. These have precise statistical meanings. Read more about this here .

- If there are graphs, do they have error bars on them? For certain types of studies, a lack of confidence intervals is a major red flag.

- The sample size. Has the study been conducted on 10, or 10,000 people? (For some research purposes, a sample size of 10 is sufficient, but for most studies larger is better).

8. Do the results answer the SPECIFIC QUESTION(S)? What do you think they mean?

Don’t move on until you have thought about this. It’s okay to change your mind in light of the authors’ interpretation—in fact you probably will if you’re still a beginner at this kind of analysis—but it’s a really good habit to start forming your own interpretations before you read those of others.

9. Read the conclusion/discussion/Interpretation section.

What do the authors think the results mean? Do you agree with them? Can you come up with any alternative way of interpreting them? Do the authors identify any weaknesses in their own study? Do you see any that the authors missed? (Don’t assume they’re infallible!) What do they propose to do as a next step? Do you agree with that?

10. Now, go back to the beginning and read the abstract.

Does it match what the authors said in the paper? Does it fit with your interpretation of the paper?

11. FINAL STEP: (Don’t neglect doing this) What do other researchers say about this paper?

Who are the (acknowledged or self-proclaimed) experts in this particular field? Do they have criticisms of the study that you haven’t thought of, or do they generally support it?

Here’s a place where I do recommend you use google! But do it last, so you are better prepared to think critically about what other people say.

(12. This step may be optional for you, depending on why you’re reading a particular paper. But for me, it’s critical! I go through the “Literature cited” section to see what other papers the authors cited. This allows me to better identify the important papers in a particular field, see if the authors cited my own papers (KIDDING!….mostly), and find sources of useful ideas or techniques.)

UPDATE: If you would like to see an example of how to read a science paper using this framework, you can find one here .

I gratefully acknowledge Professors José Bonner and Bill Saxton for teaching me how to critically read and analyze scientific papers using this method. I’m honored to have the chance to pass along what they taught me.

I’ve written a shorter version of this guide for teachers to hand out to their classes. If you’d like a PDF, shoot me an email: jenniferraff (at) utexas (dot) edu. For further comments and additional questions on this guide, please see the Comments Section on the original post .

This piece originally appeared on the author’s personal blog and is reposted with permission.

Featured image credit: Scientists in a laboratory of the University of La Rioja by Urcomunicacion (Wikimedia CC BY3.0)

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the LSE Impact blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please review our Comments Policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Jennifer Raff (Indiana University—dual Ph.D. in genetics and bioanthropology) is an assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology, University of Kansas, director and Principal Investigator of the KU Laboratory of Human Population Genomics, and assistant director of KU’s Laboratory of Biological Anthropology. She is also a research affiliate with the University of Texas anthropological genetics laboratory. She is keenly interested in public outreach and scientific literacy, writing about topics in science and pseudoscience for her blog ( violentmetaphors.com ), the Huffington Post, and for the Social Evolution Forum .

- Study Rooms

- Learning Consultations

- MINT Peer Tutoring

- SAGE Learning Communities

- Getting Started

- Peer Education Courses

- Become a Peer Educator

- ADHD/LD Support

- Workshops & Outreach

- Learning Strategies

- Manage Time

- All Resources

- Learning STEM at Duke

- For Faculty & Staff

Evaluating Information

- Understanding Primary and Secondary Sources

- Exploring and Evaluating Popular, Trade, and Scholarly Sources

Reading a Scholarly Article

Common components of original research articles, while you read, reading strategies, reading for citations, further reading, learning objectives.

This page was created to help you:

Identify the different parts of a scholarly article

Efficiently analyze and evaluate scholarly articles for usefulness

This page will focus on reading scholarly articles — published reports on original research in the social sciences, humanities, and STEM fields. Reading and understanding this type of article can be challenging. This guide will help you develop these skills, which can be learned and improved upon with practice.

We will go over:

There are many different types of articles that may be found in scholarly journals and other academic publications. For more, see:

- Types of Information Sources

Reading a scholarly article isn’t like reading a novel, website, or newspaper article. It’s likely you won’t read and absorb it from beginning to end, all at once.

Instead, think of scholarly reading as inquiry, i.e., asking a series of questions as you do your research or read for class. Your reading should be guided by your class topic or your own research question or thesis.

For example, as you read, you might ask yourself:

- What questions does it help to answer, or what topics does it address?

- Are these relevant or useful to me?

- Does the article offer a helpful framework for understanding my topic or question (theoretical framework)?

- Do the authors use interesting or innovative methods to conduct their research that might be relevant to me?

- Does the article contain references I might consult for further information?

In Practice

Scanning and skimming are essential when reading scholarly articles, especially at the beginning stages of your research or when you have a lot of material in front of you.

Many scholarly articles are organized to help you scan and skim efficiently. The next time you need to read an article, practice scanning the following sections (where available) and skim their contents:

- The abstract: This summary provides a birds’ eye view of the article contents.

- The introduction: What is the topic(s) of the research article? What is its main idea or question?

- The list of keywords or descriptors

- Methods: How did the author(s) go about answering their question/collecting their data?

- Section headings: Stop and skim those sections you may find relevant.

- Figures: Offer lots of information in quick visual format.

- The conclusion: What are the findings and/or conclusions of this article?

Mark Up Your Text

Read with purpose.

- Scanning and skimming with a pen in hand can help to focus your reading.

- Use color for quick reference. Try highlighters or some sticky notes. Use different colors to represent different topics.

- Write in the margins, putting down thoughts and questions about the content as you read.

- Use digital markup features available in eBook platforms or third-party solutions, like Adobe Reader or Hypothes.is.

Categorize Information

Create your own informal system of organization. It doesn’t have to be complicated — start basic, and be sure it works for you.

- Jot down a few of your own keywords for each article. These keywords may correspond with important topics being addressed in class or in your research paper.

- Write keywords on print copies or use the built-in note taking features in reference management tools like Zotero and EndNote.

- Your keywords and system of organization may grow more complex the deeper you get into your reading.

Highlight words, terms, phrases, acronyms, etc. that are unfamiliar to you. You can highlight on the text or make a list in a notetaking program.

- Decide if the term is essential to your understanding of the article or if you can look it up later and keep scanning.

You may scan an article and discover that it isn’t what you thought it was about. Before you close the tab or delete that PDF, consider scanning the article one more time, specifically to look for citations that might be more on-target for your topic.

You don’t need to look at every citation in the bibliography — you can look to the literature review to identify the core references that relate to your topic. Literature reviews are typically organized by subtopic within a research question or thesis. Find the paragraph or two that are closely aligned with your topic, make note of the author names, then locate those citations in the bibliography or footnote.

See the Find Articles page for what to do next:

- Find Articles

See the Citation Searching page for more on following a citation trail:

- Citation Searching

- Taking notes effectively. [blog post] Raul Pacheco-Vega, PhD

- How to read an academic paper. [video] UBCiSchool. 2013

- How to (seriously) read a scientific paper. (2016, March 21). Science | AAAS.

- How to read a paper. S. Keshav. 2007. SIGCOMM Comput. Commun. Rev. 37, 3 (July 2007), 83–84.

This guide was designed to help you:

- << Previous: Exploring and Evaluating Popular, Trade, and Scholarly Sources

- Last Updated: Feb 16, 2024 3:55 PM

- URL: https://libguides.brown.edu/evaluate

Brown University Library | Providence, RI 02912 | (401) 863-2165 | Contact | Comments | Library Feedback | Site Map

Library Intranet

- About the LSE Impact Blog

- Comments Policy

- Popular Posts

- Recent Posts

- Subscribe to the Impact Blog

- Write for us

- LSE comment

May 9th, 2016

How to read and understand a scientific paper: a guide for non-scientists.

97 comments | 2163 shares

Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

Enjoying this blogpost? 📨 Sign up to our mailing list and receive all the latest LSE Impact Blog news direct to your inbox.

My post, The truth about vaccinations: Your physician knows more than the University of Google sparked a very lively discussion, with comments from several people trying to persuade me (and the other readers) that their paper disproved everything that I’d been saying. While I encourage you to go read the comments and contribute your own, here I want to focus on the much larger issue that this debate raised: what constitutes scientific authority?

It’s not just a fun academic problem. Getting the science wrong has very real consequences. For example, when a community doesn’t vaccinate children because they’re afraid of “toxins” and think that prayer (or diet, exercise, and “clean living”) is enough to prevent infection, outbreaks happen .

“Be skeptical. But when you get proof, accept proof.” –Michael Specter

What constitutes enough proof? Obviously everyone has a different answer to that question. But to form a truly educated opinion on a scientific subject, you need to become familiar with current research in that field. And to do that, you have to read the “primary research literature” (often just called “the literature”). You might have tried to read scientific papers before and been frustrated by the dense, stilted writing and the unfamiliar jargon. I remember feeling this way! Reading and understanding research papers is a skill which every single doctor and scientist has had to learn during graduate school. You can learn it too, but like any skill it takes patience and practice.

I want to help people become more scientifically literate, so I wrote this guide for how a layperson can approach reading and understanding a scientific research paper. It’s appropriate for someone who has no background whatsoever in science or medicine, and based on the assumption that he or she is doing this for the purpose of getting a basic understanding of a paper and deciding whether or not it’s a reputable study.

The type of scientific paper I’m discussing here is referred to as a primary research article . It’s a peer-reviewed report of new research on a specific question (or questions). Another useful type of publication is a review article . Review articles are also peer-reviewed, and don’t present new information, but summarize multiple primary research articles, to give a sense of the consensus, debates, and unanswered questions within a field. (I’m not going to say much more about them here, but be cautious about which review articles you read. Remember that they are only a snapshot of the research at the time they are published. A review article on, say, genome-wide association studies from 2001 is not going to be very informative in 2013. So much research has been done in the intervening years that the field has changed considerably).

Before you begin: some general advice

Reading a scientific paper is a completely different process than reading an article about science in a blog or newspaper. Not only do you read the sections in a different order than they’re presented, but you also have to take notes, read it multiple times, and probably go look up other papers for some of the details. Reading a single paper may take you a very long time at first. Be patient with yourself. The process will go much faster as you gain experience.

Most primary research papers will be divided into the following sections: Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results, and Conclusions/Interpretations/Discussion. The order will depend on which journal it’s published in. Some journals have additional files (called Supplementary Online Information) which contain important details of the research, but are published online instead of in the article itself (make sure you don’t skip these files).

Before you begin reading, take note of the authors and their institutional affiliations. Some institutions (e.g. University of Texas) are well-respected; others (e.g. the Discovery Institute ) may appear to be legitimate research institutions but are actually agenda-driven. Tip: g oogle “Discovery Institute” to see why you don’t want to use it as a scientific authority on evolutionary theory.

Also take note of the journal in which it’s published. Reputable (biomedical) journals will be indexed by Pubmed . [EDIT: Several people have reminded me that non-biomedical journals won’t be on Pubmed, and they’re absolutely correct! (thanks for catching that, I apologize for being sloppy here). Check out Web of Science for a more complete index of science journals. And please feel free to share other resources in the comments!] Beware of questionable journals .

As you read, write down every single word that you don’t understand. You’re going to have to look them all up (yes, every one. I know it’s a total pain. But you won’t understand the paper if you don’t understand the vocabulary. Scientific words have extremely precise meanings).

Step-by-step instructions for reading a primary research article

1. Begin by reading the introduction, not the abstract.

The abstract is that dense first paragraph at the very beginning of a paper. In fact, that’s often the only part of a paper that many non-scientists read when they’re trying to build a scientific argument. (This is a terrible practice—don’t do it.). When I’m choosing papers to read, I decide what’s relevant to my interests based on a combination of the title and abstract. But when I’ve got a collection of papers assembled for deep reading, I always read the abstract last. I do this because abstracts contain a succinct summary of the entire paper, and I’m concerned about inadvertently becoming biased by the authors’ interpretation of the results.

2. Identify the BIG QUESTION.

Not “What is this paper about”, but “What problem is this entire field trying to solve?”

This helps you focus on why this research is being done. Look closely for evidence of agenda-motivated research.

3. Summarize the background in five sentences or less.

Here are some questions to guide you:

What work has been done before in this field to answer the BIG QUESTION? What are the limitations of that work? What, according to the authors, needs to be done next?

The five sentences part is a little arbitrary, but it forces you to be concise and really think about the context of this research. You need to be able to explain why this research has been done in order to understand it.

4. Identify the SPECIFIC QUESTION(S)

What exactly are the authors trying to answer with their research? There may be multiple questions, or just one. Write them down. If it’s the kind of research that tests one or more null hypotheses, identify it/them.

Not sure what a null hypothesis is? Go read this , then go back to my last post and read one of the papers that I linked to (like this one ) and try to identify the null hypotheses in it. Keep in mind that not every paper will test a null hypothesis.

5. Identify the approach

What are the authors going to do to answer the SPECIFIC QUESTION(S)?

6. Now read the methods section. Draw a diagram for each experiment, showing exactly what the authors did.

I mean literally draw it. Include as much detail as you need to fully understand the work. As an example, here is what I drew to sort out the methods for a paper I read today ( Battaglia et al. 2013: “The first peopling of South America: New evidence from Y-chromosome haplogroup Q” ). This is much less detail than you’d probably need, because it’s a paper in my specialty and I use these methods all the time. But if you were reading this, and didn’t happen to know what “process data with reduced-median method using Network” means, you’d need to look that up.

Image credit: author

You don’t need to understand the methods in enough detail to replicate the experiment—that’s something reviewers have to do—but you’re not ready to move on to the results until you can explain the basics of the methods to someone else.

7. Read the results section. Write one or more paragraphs to summarize the results for each experiment, each figure, and each table. Don’t yet try to decide what the results mean , just write down what they are.

You’ll find that, particularly in good papers, the majority of the results are summarized in the figures and tables. Pay careful attention to them! You may also need to go to the Supplementary Online Information file to find some of the results.

It is at this point where difficulties can arise if statistical tests are employed in the paper and you don’t have enough of a background to understand them. I can’t teach you stats in this post, but here , here , and here are some basic resources to help you. I STRONGLY advise you to become familiar with them.

Things to pay attention to in the results section:

- Any time the words “significant” or “non-significant” are used. These have precise statistical meanings. Read more about this here .

- If there are graphs, do they have error bars on them? For certain types of studies, a lack of confidence intervals is a major red flag.

- The sample size. Has the study been conducted on 10, or 10,000 people? (For some research purposes, a sample size of 10 is sufficient, but for most studies larger is better).

8. Do the results answer the SPECIFIC QUESTION(S)? What do you think they mean?

Don’t move on until you have thought about this. It’s okay to change your mind in light of the authors’ interpretation—in fact you probably will if you’re still a beginner at this kind of analysis—but it’s a really good habit to start forming your own interpretations before you read those of others.

9. Read the conclusion/discussion/Interpretation section.

What do the authors think the results mean? Do you agree with them? Can you come up with any alternative way of interpreting them? Do the authors identify any weaknesses in their own study? Do you see any that the authors missed? (Don’t assume they’re infallible!) What do they propose to do as a next step? Do you agree with that?

10. Now, go back to the beginning and read the abstract.

Does it match what the authors said in the paper? Does it fit with your interpretation of the paper?

11. FINAL STEP: (Don’t neglect doing this) What do other researchers say about this paper?

Who are the (acknowledged or self-proclaimed) experts in this particular field? Do they have criticisms of the study that you haven’t thought of, or do they generally support it?

Here’s a place where I do recommend you use google! But do it last, so you are better prepared to think critically about what other people say.

(12. This step may be optional for you, depending on why you’re reading a particular paper. But for me, it’s critical! I go through the “Literature cited” section to see what other papers the authors cited. This allows me to better identify the important papers in a particular field, see if the authors cited my own papers (KIDDING!….mostly), and find sources of useful ideas or techniques.)

UPDATE: If you would like to see an example of how to read a science paper using this framework, you can find one here .

I gratefully acknowledge Professors José Bonner and Bill Saxton for teaching me how to critically read and analyze scientific papers using this method. I’m honored to have the chance to pass along what they taught me.

I’ve written a shorter version of this guide for teachers to hand out to their classes. If you’d like a PDF, shoot me an email: jenniferraff (at) utexas (dot) edu. For further comments and additional questions on this guide, please see the Comments Section on the original post .

This piece originally appeared on the author’s personal blog and is reposted with permission.

Featured image credit: Scientists in a laboratory of the University of La Rioja by Urcomunicacion (Wikimedia CC BY3.0)

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the LSE Impact blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please review our Comments Policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

About the Author

Jennifer Raff (Indiana University—dual Ph.D. in genetics and bioanthropology) is an assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology, University of Kansas, director and Principal Investigator of the KU Laboratory of Human Population Genomics, and assistant director of KU’s Laboratory of Biological Anthropology. She is also a research affiliate with the University of Texas anthropological genetics laboratory. She is keenly interested in public outreach and scientific literacy, writing about topics in science and pseudoscience for her blog ( violentmetaphors.com ), the Huffington Post , and for the Social Evolution Forum .

About the author

97 Comments

Very good Indeed.I always Read Abstract First Time always ……Thanks

Great information and guide to reading and understanding scientific paper. However, there are non-scientific student asked to do scientific research and it would be great to actually give an example and you point out the answers to the steps in the sample article or journal cited. Thank you.

- Pingback: Very useful (for scientists too): How to read and understand a scientific paper: a guide for non-scientists – microBEnet: the microbiology of the Built Environment network.

- Pingback: Reader beware | Liblog

- Pingback: Research Roundup: DOAJ’s Clean Sweep, A.I. In The Classroom And More | PLOS Blogs Network

I can summarize it eve further: three stars by a number in a table = good, no stars = bad

within the context of the fact that a very sizable portion of scientific papers are falsified, what does this article mean?

Your “fact” needs explanation and evidence, otherwise it can be considered alternative.

That’s why you don’t skip step 11

I think it would be useful also to point out that, even after diligently pursuing all of these excellent steps, the reader is usually still unable to determine whether the subjects or materials even existed. Unlike with lay media, where most important stories are covered by multiple sources, and where facts are sometimes checkable from primary sources – even by readers – it is rare indeed that a reader can go beyond the words on the page.

Is the fact that you read instructions on how to read a paper not evidence that there is something wrong with the way we write papers?

The issue of scientific literacy is always challenging for my students. But this is the most practical and helpful guide I’ve ever seen on the web, thanks for this. I usually share with my students the following tips already mentioned above: – Learn the vocabulary before reading – Summarize the background in five sentences or less – Identify the BIG QUESTION

But the pieces of advice this guide gives are structured better and easier. I especially love this one: Don’t yet try to decide what the results mean, just write down what they are. Thanks again for writing this piece!

- Pingback: Como ler um artigo científico – um guia para não-cientistas | Antônio Carlos Lessa

you left out ask for the data, so you can check for yourself… (ie trust but verify)

an example a psychology paper that surveyed a group of people about conspiracy theories (n=137) and it’s main/only novel finding was that people that believed in conspiracies theories, there was a tendency for people to believe in mutually contradictory conspiracy theories. ie individual could believe that Princess Diana faked her own death, whilst at the same time had been murdered by MI5

The paper, was duly called – Dead and Alive – M Wood et al…

However. after requesting the data. there was not a single individual person that ticked the survey boxes, that simultaneously believed this finding. Not one person.

The problem, most people surveyed did not believe either of those conspiracies, and inappropriate stats method was applied to data, that assumed a non skewed dataset. Thus, not believing in A and not believing in B correlated, but it also gave a ‘result that believing in A, and Believing in B also correlated..

A very dumb paper… Author still hasn’t retracted it yet.

- Pingback: How to Read a Scientific Paper as a Non-Scientist » Public(s) Sociology

I love this! Great simmered-down resource for my undergrads- both science and non-science majors. Thanks for sharing!

“Web of Science” link is broken (at least for me) but a useable alternative is webofknowledge.com (same resource, different name).

I think it is important to note that the journal in which a paper is published is no proof as to the rigor of that paper. A listing in PubMed does not guarantee quality; thus, you need to focus on teaching people how to interpret the paper without relying on a simple JTASS approach to initial assessment. This may be a guide, but nothing more. I say this as a former editor of a MEDLINE journal. There can be good papers in bad journals and bad papers in good ones. But you are correct. Key questions are: What is the question? How will we answer the question? What answer did we get? Did we use the right tools to answer the question? What do we think it means? What else could we do? And thus we can train people to watch for sleights of hand, such as shifting primary outcomes, data mining, salami slicing, etc.

- Pingback: How to read and understand a scientific paper: a guide for non-scientists – Sociology of Knowledge

Yikes! This is a lot of work just to read a single paper! It’s almost the same as writing a paper! I understand the logic in why you recommend this, but the average person is going to be willing to spend 20-30 minutes reading and trying to learn. This method calls for multiple hours of effort and I just don’t seem many non-scientist people being willing to do that when they’re more curious than actually invested. I was really hoping this entry was going to make it easier to navigate the foreign and confusing world that these papers represent, and it probably will if someone does this process repeatedly for quite some time…..like a scientist…..but most of us aren’t scientists and don’t have that kind of time to dedicate to something that’s not our work or family.

By tradition, we expect our scientists to report their findings by codifying them in unreadable gobbledygook. Then we write instructions on how to decode that unreadable nonsense!!

We need to encourage papers to be written in everyday language so it is easier for all. Problem solved.

I wholeheartedly agree with Kaveh Bazargan. From personal experience as a non-scientist trying to do this with medical research papers is a very intimidating and isolating experience. Most people don’t have the time spare to even try to learn this skill. It would be great if systematic reviewers who are acknowledged experts in reading and analysing papers could find a way of communicating the important information about individual papers to non-scientists before – or instead of – burying them in systematic reviews and meta-analyses which are even more difficult to understand. Structured plain language summaries of primary research would be very helpful rather than individuals having to teach themselves how to read and understand a scientific paper which is written for other scientists in “unreadable goggledygook”. Many (most?) papers conceal methodogical flaws in the research conduct which are almost impossible to spot without years of scientific training.

I love this! Extraordinary cooled off assets for my students both science and non-science majors. A debt of gratitude is in order for sharing!

Regarding step 11, if you have access to Web of Science I recommend looking up how many citations the paper has (this will also vary depending on the age of the paper) and who cites it, and whether there even any replies to it in the peer-reviewed literature.

Do you literally do this for every paper you read? I’m curious how much time it takes you to go from start to finish on what you would consider a typical paper. How often do you read new articles a week?

This post has the laudable goal of helping nonscientists understand the primary literature, but the recommendations seem even more onerous than they have to be. For example, the idea that one should write down every single word that he/she doesn’t know? That sounds more like a task for a scientist scrutinizing the work of a rival. For a nonscientist, there may be dozens and dozens of unknown words, and chasing down the meaning of each one may cause a serious forest/trees problem. I agree that there’s no substitute for the hard work of digging into a paper, but following the prescribed advice to the letter would be utterly exhausting for almost any lay reader. I base these comments on my experiences as a biology researcher and undergraduate instructor.

- Pingback: How to read and understand a scientific paper: a guide for non-scientists – Agriculture Blog!

- Pingback: The Literary Drover No. 354 | The Literary Drover

- Pingback: Weekly Digest – February 6-12 – Austin Science Advocates

- Pingback: Impact of Social Sciences – How to read and understand a scientific paper: a guide for non-scientists | ARC Playground

I really like your post and the effort, but much of the problem wouldn’t exist if we, academics, did a better job in writing down the correct conclusions. Researcher degrees of freedom are seldom properly understood and we keep on having the tendency to be overdeterministic about statistics that are not intended as such. Of course we want to communicate in black and white about our tests (significance!) because it is a human tendency to persuade the reader. Most of the research probably is not as inconsistent as it first seems but we forget to report the proper statistics to see so (CI around the ES)

- Pingback: Rare Disease Research – moving from Study Participant to Research Partner | hcldr

- Pingback: Tips on Reading Scientific Papers – The Inner Scientist

- Pingback: How to read and understand a scientific paper | EDS and Chronic Pain News & Info

Thank you very much for sharing a guide that will help me to follow the best standards for writing a scientific paper even I am not a scientist.

- Pingback: Știința din spatele convingerii – 24 de ore

- Pingback: How to read and understand a scientific paper: A guide for non-scientists. | Climate Change

Reading the abstract last is one, not the, way to read a paper. It it biases the naive reader, then they are not reviewing with a level of skepticism required to evaluate science. We put abstracts first because they lay out the problem, overview the sample and design, and tersely describe what they think they discovered. Then, as I read, I have a roadmap in my head of what to look for to determine for myself whether or not they found something noteworthy.

What is the problem? Are hypotheses to be tested likely to illuminate/clarify the problem? Is the sample appropriate for testing and was it sampled without imputing bias? Were measures appropriate and do they have a history of validity? We the analytics applied appropriate for testing at the level of power needed give the sample size? [Here even many scientist are ill-equipped to judge.] After enumerating results, do the authors list weaknesses in their design that might suggest replication is necessary? If not, check for snow – as in snowjob. If significance levelsare low or variables correlate with one another too much, are moderators discussed? [e.g., results hold for males but not females, old vs young, fat vs skinny, etc.). If so, why were data not re-analyzed to control for moderator effects on results?

Lastly, if the word “prove” appears anywhere in the paper, assume it is junk science (like fake news). Research is never ever done to prove anything. Research is only done to find out. Once a preponderance of studies report a similar finding looking at the same problem with different people, measures, designs, and statistical analyses, then you have something like proof; consensus.

Lastly, if you are a conspiracy theory believer, you will disbelieve any scientific study that does not support your word view. Keep this in mind. A few studies that run counter to the prevailing consensus is not PROOF that your conspiracy is correct, and mainstream science is wrong. I do not know a single scientist (and I know thousands globally) who do not consider climate change to be well-evidenced. Similarly, evolutionary theory remains useful – our current understanding of genomic medicine hinges on cellular mutation, which is evolution on a microscopic scale.

This is a very useful set of instructions, but I found the following statement highly amusing: “Before you begin reading, take note of the authors and their institutional affiliations. Some institutions (e.g. University of Texas) are well-respected; others (e.g. the Discovery Institute) may appear to be legitimate research institutions but are actually agenda-driven.”

All research institutions are agenda driven (including my alma mater, the University of Texas), because funding and professional advancement depend on results. Researchers are fallible humans and subject to temptation and error. There is a very big lawsuit pending against Duke University (see below) for falsifying data.

When I read any research (especially medical), I now search for evidence of legal or professional action. So you might add that as #12: “Lawsuits? Retractions?” Caveat lector.

http://science.sciencemag.org/content/353/6303/977.full

http://www.dukechronicle.com/article/2016/09/experts-address-research-fabrication-lawsuit-against-duke-note-litigation-could-be-protracted

- Pingback: Four short links: 27 June 2017 | Vedalgo

- Pingback: How to read and understand a scientific paper: a guide for non-scientists | ExtendTree

- Pingback: Bookmarks for June 26th through June 27th | Chris's Digital Detritus

- Pingback: Four short links: 27 June 2017 | A bunch of data

Weird advice, like: ‘I always read the abstract last’ . This is advice for referees, not for general readers. I always read the abstract first.

An abstract can be misleading, but I am often not qualified enough to judge that. Actually, this blog post title and abstract are misleading too: your advice is for referees, not for non-scientists. So you wanted to provide an immersive experience into a misleading piece, well done 😉

First thing, get rid of the word proof. This is a huge error in that even if you have reputable scientists, journals, institutions, etc. that what is published, especially in a single article, is anything resembling a fact. It is merely research findings from one instance and in no way forms a fact. This is the next level of misinterpretation of science, even among those able to comprehend the journal article, that science produces or discovers facts. There is nothing that is factual that we know of.

Several comments:

For the mid-term exam in a graduate class I took in experimental design the professor would select half a dozen articles from the peer reviewed literature, tell her students to pick three and explain what they had done wrong. New articles for every class and she never ran out.

Beware of articles published in inappropriate journals, no matter how respectable (E.g., something about sociology or criminology published in a medical journal). This is a strategy for sneaking agenda driven research past the peer review process by going to a journal whose reviewers are likely to be unfamiliar with the subject while the editors are sympathetic to the agenda.

There is a reason research papers are written in what looks like “scientific gobbledygook” to lay persons. They are not intended for a lay audience and the goal is to be extremely precise with the technical details of what was done and found so other scientists can examine the results and, most important, attempt to replicate them.. There is no way to simplify the language and put it in lay terms without losing the precision required for a scientific study. E.g., a particle physicist may give a lay explanation of an experiment in metaphorical terms of little balls of energy smashing into each other, but their peers are going to want to see the pages and pages of mathematics that really describe what was happening.

- Pingback: Climate News: Top Stories for the Week of June 24-30 - ecoAmerica

I would add “Check the source of funding for the research.” If paper on the safety of glyphosate is funded by Bayer or Monsanto, or a paper on climactic change is funded by Exxon, read no further.

- Pingback: Stats Trek IV | The IAABC Journal

Get the dissertation writing service students look for these days with the prime focus being creating a well researched and lively content on any topic.

The non-scientist should pay extra attention towards this article for the non-technical writing and understanding for them.

A lot of a researcher’s work includes perusing research papers, regardless of whether it’s to remain progressive in their field, propel their logical comprehension, survey compositions, or assemble data for a task proposition or concede application. Since logical articles are not the same as different writings, similar to books or daily paper stories, they ought to be perused in an unexpected way.

- Pingback: 2017 – collected articles – The Old Git's Cave

Thanks, I’ll use this a lot for my MSc Thesis.

Those are some great tips but please don’t forget that each school has its own requirements to academic papers.

Clarifying your methodology for reading science paper: excellent idea and great information. Thanks a lot!

Thanks for sharing this blog. Its very helpful for me and I bookmarked this for future

Excelente trabajo, original. Lo recomendaré para mis estudiantes de Posgrado. Si no hay problema, me gustaría hacer una traducción al castellano para el uso de mis estudiantes de pregrado de Sociología.

Excellent work,original. I will recommend it for my graduate students. If there is no problem, I would like to make a translation into Spanish for the use of my undergraduate Sociology students.

Hi Luis, all our works are CC licensed so you are more than welcome to make a translation provided you link back to the original source. See here for details: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en_GB

Great information , it is very helpful thanks for sharing the blog .

Step 1 and 10 is a great idea, but I still think it’s possible to read the abstract with the introduction and still keep an open mind? and shouldn’t they keep their results for the interpretation section? sorry new to reading scientific papers

Step 1 and 10 is a great idea, but I still think it’s possible to read the abstract with the introduction and still keep an open mind? and shouldn’t they keep their results for the interpretation section? sorry new to reading scientific papers

- Pingback: Eight Blogging Mistakes Which Most Beginners Make | Congress of International Society of Peritoneal Dialysis

- Pingback: Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) is a rare and often fatal form of breast cancer. In IBC, lymphatic vessels in the skin are blocked causing the breasts to appear swollen and red. - Versed Writers

- Pingback: Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) is a rare and often fatal form of breast cancer. In IBC, lymphatic vessels in the skin are blocked causing the breasts to appear swollen and red. – essay studess

Thank you for sharing the tips, they were very helpful.

- Pingback: Introduce Yourself (Example Post) – Dr. Hemachandran Nair G

The article is extremely helpful. Considering that scientific research are not as easy, the tips in the article are great.

- Pingback: Seattle: notes from a pandemic: 9 | Genevieve Williams

Thank you for posting this. It has really helped a lot, especially for those of us who always read the abstract first haha

Thanks for writing this blog. It is very much informative and at the same time useful for me

Yeah, great advice on how to be objective from someone who openly declares their prejudice in the opening statement.

- Pingback: How to Read and Understand a Scientific Paper -

- Pingback: Mirroring your partner’s stress, if your partner is anxious – Celia Smith

Do you in a real sense do this for each paper you read? I’m interested what amount of time it requires for you to go beginning to end on what you would think about an average paper. How frequently do you read new articles seven days?

- Pingback: CRAFT: Writing Science by Sarah Boon | Hippocampus Magazine - Memorable Creative Nonfiction

- Pingback: HOW TO READ AND UNDERSTAND A SCIENTIFIC PAPER FOR NON-SCIENTIST – KALISHAAR

That is literally my question too, I see it as quite time consuming to conduct such a lengthy process for all scientific articles we come across especially as one has other responsibilities to give attention too

- Pingback: Straight from the horse’s mouth: How to read (and hopefully understand) a scientific research paper – Notes from a small scientist

- Pingback: How to read cannabis research papers | Toronto Cannabis Delivery - Toronto Relief Chronic Pain

- Pingback: How to read cannabis research papers - Social Pothead

- Pingback: 2 – Cory Doctorow on unfair contracts for writers - Traffic Ventures

There is a reason research papers are written in what looks like “scientific gobbledygook” to lay persons. They are not intended for a lay audience and the goal is to be extremely precise with the technical details of what was done and found so other scientists can examine the results and, most important, attempt o replicate them.

- Pingback: How to Read Cannabis Research Papers – BARC Collective

- Pingback: Your 3-Step Guide to Start Reading Research Papers

- Pingback: How to Read Cannabis Research Papers - BARC Collective

Thanks for posting this. You are doing a service to the general public and also graduate students by not only posting this but answering all sincere questions. I have a Ph. D. in Zoology and have been a peer-reviewer for at least 12 papers and am first author of three peer-reviewed papers. I have taught statistics in two universities as a contract professor and all of my papers rely on use of statistics. To answer a frequently asked question, yes, personally it can take me a couple of hours or several more to read some papers. This is true for my colleagues as well. Scientific papers are written so as to be as concise as possible and this can make them hard to read. They often also use technical terms which one has to look up. At least biology and statistics. nothing I have read (or written) has been in “goobledygook” or purposely incomprehensible jargon but they do use terms and concepts that are probably unfamiliar to the layman. I think what the author means, by her comment on absstracts can be intepreted as “don’t JUST read the abstract. Be sure to read the introduction. Personally I go to the discussion and conclusion next.

- Pingback: Bagaimana Cara Download Jurnal Gratis Itu? - EMAF

- Pingback: How to read a clinical research study about trichotillomania

- Pingback: Reading studies: Resources – 495R Research Studies

Your writing skills and passion for sharing your knowledge and experiences are truly outstanding. . Keep writing and inspiring others with your words.

I would add, look at who funded the study and their financial interests. Most science is not independent it is funded by those with an agenda. Look at the demographic data, length of time the study took place, what was left out, where you might need more information. Look at who was included and excluded in the data set. Anyone that has taken statistics knows what you include or exclude in the data set can skew and or outright change the outcome.

- Pingback: Undergraduate Economics Resources – tanvi madhaw

- Pingback: How Do I Critically Consume Quantitative Research?

Thanks for sharing such nice information. I read journals and scientific articles a lot. I had a lot ot trouble. but reading this article has cleared many basic concepts for me.

Thanks for sharing this article. Helped me a lot.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Related Posts

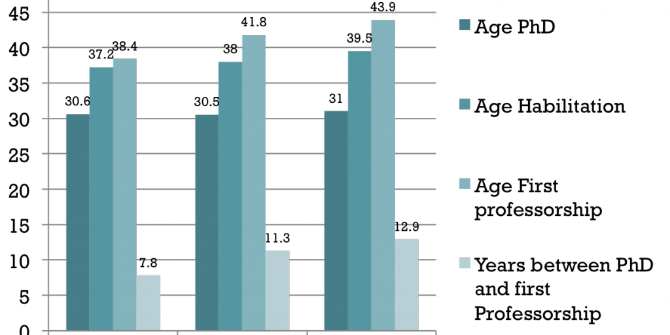

How Academia Resembles a Drug Gang

December 11th, 2013.

What would honest university rankings look like?

September 11th, 2023.

When publishing becomes the sole focus of PhD programmes academia suffers

December 5th, 2022.

Student evaluations of teaching are not only unreliable, they are significantly biased against female instructors.

February 4th, 2016.

Visit our sister blog LSE Review of Books

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Ten simple rules for reading a scientific paper

Maureen a carey, kevin l steiner, william a petri jr.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

* E-mail: [email protected]

Collection date 2020 Jul.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

“There is no problem that a library card can't solve” according to author Eleanor Brown [ 1 ]. This advice is sound, probably for both life and science, but even the best tool (like the library) is most effective when accompanied by instructions and a basic understanding of how and when to use it.

For many budding scientists, the first day in a new lab setting often involves a stack of papers, an email full of links to pertinent articles, or some promise of a richer understanding so long as one reads enough of the scientific literature. However, the purpose and approach to reading a scientific article is unlike that of reading a news story, novel, or even a textbook and can initially seem unapproachable. Having good habits for reading scientific literature is key to setting oneself up for success, identifying new research questions, and filling in the gaps in one’s current understanding; developing these good habits is the first crucial step.

Advice typically centers around two main tips: read actively and read often. However, active reading, or reading with an intent to understand, is both a learned skill and a level of effort. Although there is no one best way to do this, we present 10 simple rules, relevant to novices and seasoned scientists alike, to teach our strategy for active reading based on our experience as readers and as mentors of undergraduate and graduate researchers, medical students, fellows, and early career faculty. Rules 1–5 are big picture recommendations. Rules 6–8 relate to philosophy of reading. Rules 9–10 guide the “now what?” questions one should ask after reading and how to integrate what was learned into one’s own science.

Rule 1: Pick your reading goal

What you want to get out of an article should influence your approach to reading it. Table 1 includes a handful of example intentions and how you might prioritize different parts of the same article differently based on your goals as a reader.

Table 1. Reading intentions and how it might influence your approach.

1 Yay! Welcome!

2 A journal club is when a group of scientists get together to discuss a paper. Usually one person leads the discussion and presents all of the data. The group discusses their own interpretations and the authors’ interpretation.

Rule 2: Understand the author’s goal

In written communication, the reader and the writer are equally important. Both influence the final outcome: in this case, your scientific understanding! After identifying your goal, think about the author’s goal for sharing this project. This will help you interpret the data and understand the author’s interpretation of the data. However, this requires some understanding of who the author(s) are (e.g., what are their scientific interests?), the scientific field in which they work (e.g., what techniques are available in this field?), and how this paper fits into the author’s research (e.g., is this work building on an author’s longstanding project or controversial idea?). This information may be hard to glean without experience and a history of reading. But don’t let this be a discouragement to starting the process; it is by the act of reading that this experience is gained!

A good step toward understanding the goal of the author(s) is to ask yourself: What kind of article is this? Journals publish different types of articles, including methods, review, commentary, resources, and research articles as well as other types that are specific to a particular journal or groups of journals. These article types have different formatting requirements and expectations for content. Knowing the article type will help guide your evaluation of the information presented. Is the article a methods paper, presenting a new technique? Is the article a review article, intended to summarize a field or problem? Is it a commentary, intended to take a stand on a controversy or give a big picture perspective on a problem? Is it a resource article, presenting a new tool or data set for others to use? Is it a research article, written to present new data and the authors’ interpretation of those data? The type of paper, and its intended purpose, will get you on your way to understanding the author’s goal.

Rule 3: Ask six questions

When reading, ask yourself: (1) What do the author(s) want to know (motivation)? (2) What did they do (approach/methods)? (3) Why was it done that way (context within the field)? (4) What do the results show (figures and data tables)? (5) How did the author(s) interpret the results (interpretation/discussion)? (6) What should be done next? (Regarding this last question, the author(s) may provide some suggestions in the discussion, but the key is to ask yourself what you think should come next.)

Each of these questions can and should be asked about the complete work as well as each table, figure, or experiment within the paper. Early on, it can take a long time to read one article front to back, and this can be intimidating. Break down your understanding of each section of the work with these questions to make the effort more manageable.

Rule 4: Unpack each figure and table

Scientists write original research papers primarily to present new data that may change or reinforce the collective knowledge of a field. Therefore, the most important parts of this type of scientific paper are the data. Some people like to scrutinize the figures and tables (including legends) before reading any of the “main text”: because all of the important information should be obtained through the data. Others prefer to read through the results section while sequentially examining the figures and tables as they are addressed in the text. There is no correct or incorrect approach: Try both to see what works best for you. The key is making sure that one understands the presented data and how it was obtained.

For each figure, work to understand each x- and y-axes, color scheme, statistical approach (if one was used), and why the particular plotting approach was used. For each table, identify what experimental groups and variables are presented. Identify what is shown and how the data were collected. This is typically summarized in the legend or caption but often requires digging deeper into the methods: Do not be afraid to refer back to the methods section frequently to ensure a full understanding of how the presented data were obtained. Again, ask the questions in Rule 3 for each figure or panel and conclude with articulating the “take home” message.

Rule 5: Understand the formatting intentions

Just like the overall intent of the article (discussed in Rule 2), the intent of each section within a research article can guide your interpretation. Some sections are intended to be written as objective descriptions of the data (i.e., the Results section), whereas other sections are intended to present the author’s interpretation of the data. Remember though that even “objective” sections are written by and, therefore, influenced by the authors interpretations. Check out Table 2 to understand the intent of each section of a research article. When reading a specific paper, you can also refer to the journal’s website to understand the formatting intentions. The “For Authors” section of a website will have some nitty gritty information that is less relevant for the reader (like word counts) but will also summarize what the journal editors expect in each section. This will help to familiarize you with the goal of each article section.

Table 2. The structure of a primary research article.

Research articles typically contain each of these sections, although sometimes the “results” and “discussion” sections (or “discussion” and “conclusion” sections) are merged into one section. Additional sections may be included, based on request of the journal or the author(s). Keep in mind: If it was included, someone thought it was important for you to read.

Rule 6: Be critical

Published papers are not truths etched in stone. Published papers in high impact journals are not truths etched in stone. Published papers by bigwigs in the field are not truths etched in stone. Published papers that seem to agree with your own hypothesis or data are not etched in stone. Published papers that seem to refute your hypothesis or data are not etched in stone.

Science is a never-ending work in progress, and it is essential that the reader pushes back against the author’s interpretation to test the strength of their conclusions. Everyone has their own perspective and may interpret the same data in different ways. Mistakes are sometimes published, but more often these apparent errors are due to other factors such as limitations of a methodology and other limits to generalizability (selection bias, unaddressed, or unappreciated confounders). When reading a paper, it is important to consider if these factors are pertinent.

Critical thinking is a tough skill to learn but ultimately boils down to evaluating data while minimizing biases. Ask yourself: Are there other, equally likely, explanations for what is observed? In addition to paying close attention to potential biases of the study or author(s), a reader should also be alert to one’s own preceding perspective (and biases). Take time to ask oneself: Do I find this paper compelling because it affirms something I already think (or wish) is true? Or am I discounting their findings because it differs from what I expect or from my own work?

The phenomenon of a self-fulfilling prophecy, or expectancy, is well studied in the psychology literature [ 2 ] and is why many studies are conducted in a “blinded” manner [ 3 ]. It refers to the idea that a person may assume something to be true and their resultant behavior aligns to make it true. In other words, as humans and scientists, we often find exactly what we are looking for. A scientist may only test their hypotheses and fail to evaluate alternative hypotheses; perhaps, a scientist may not be aware of alternative, less biased ways to test her or his hypothesis that are typically used in different fields. Individuals with different life, academic, and work experiences may think of several alternative hypotheses, all equally supported by the data.

Rule 7: Be kind

The author(s) are human too. So, whenever possible, give them the benefit of the doubt. An author may write a phrase differently than you would, forcing you to reread the sentence to understand it. Someone in your field may neglect to cite your paper because of a reference count limit. A figure panel may be misreferenced as Supplemental Fig 3E when it is obviously Supplemental Fig 4E. While these things may be frustrating, none are an indication that the quality of work is poor. Try to avoid letting these minor things influence your evaluation and interpretation of the work.

Similarly, if you intend to share your critique with others, be extra kind. An author (especially the lead author) may invest years of their time into a single paper. Hearing a kindly phrased critique can be difficult but constructive. Hearing a rude, brusque, or mean-spirited critique can be heartbreaking, especially for young scientists or those seeking to establish their place within a field and who may worry that they do not belong.

Rule 8: Be ready to go the extra mile

To truly understand a scientific work, you often will need to look up a term, dig into the supplemental materials, or read one or more of the cited references. This process takes time. Some advisors recommend reading an article three times: The first time, simply read without the pressure of understanding or critiquing the work. For the second time, aim to understand the paper. For the third read through, take notes.

Some people engage with a paper by printing it out and writing all over it. The reader might write question marks in the margins to mark parts (s)he wants to return to, circle unfamiliar terms (and then actually look them up!), highlight or underline important statements, and draw arrows linking figures and the corresponding interpretation in the discussion. Not everyone needs a paper copy to engage in the reading process but, whatever your version of “printing it out” is, do it.

Rule 9: Talk about it

Talking about an article in a journal club or more informal environment forces active reading and participation with the material. Studies show that teaching is one of the best ways to learn and that teachers learn the material even better as the teaching task becomes more complex [ 4 – 5 ]; anecdotally, such observations inspired the phrase “to teach is to learn twice.”

Beyond formal settings such as journal clubs, lab meetings, and academic classes, discuss papers with your peers, mentors, and colleagues in person or electronically. Twitter and other social media platforms have become excellent resources for discussing papers with other scientists, the public or your nonscientist friends, or even the paper’s author(s). Describing a paper can be done at multiple levels and your description can contain all of the scientific details, only the big picture summary, or perhaps the implications for the average person in your community. All of these descriptions will solidify your understanding, while highlighting gaps in your knowledge and informing those around you.

Rule 10: Build on it

One approach we like to use for communicating how we build on the scientific literature is by starting research presentations with an image depicting a wall of Lego bricks. Each brick is labeled with the reference for a paper, and the wall highlights the body of literature on which the work is built. We describe the work and conclusions of each paper represented by a labeled brick and discuss each brick and the wall as a whole. The top brick on the wall is left blank: We aspire to build on this work and label this brick with our own work. We then delve into our own research, discoveries, and the conclusions it inspires. We finish our presentations with the image of the Legos and summarize our presentation on that empty brick.

Whether you are reading an article to understand a new topic area or to move a research project forward, effective learning requires that you integrate knowledge from multiple sources (“click” those Lego bricks together) and build upwards. Leveraging published work will enable you to build a stronger and taller structure. The first row of bricks is more stable once a second row is assembled on top of it and so on and so forth. Moreover, the Lego construction will become taller and larger if you build upon the work of others, rather than using only your own bricks.

Build on the article you read by thinking about how it connects to ideas described in other papers and within own work, implementing a technique in your own research, or attempting to challenge or support the hypothesis of the author(s) with a more extensive literature review. Integrate the techniques and scientific conclusions learned from an article into your own research or perspective in the classroom or research lab. You may find that this process strengthens your understanding, leads you toward new and unexpected interests or research questions, or returns you back to the original article with new questions and critiques of the work. All of these experiences are part of the “active reading”: process and are signs of a successful reading experience.

In summary, practice these rules to learn how to read a scientific article, keeping in mind that this process will get easier (and faster) with experience. We are firm believers that an hour in the library will save a week at the bench; this diligent practice will ultimately make you both a more knowledgeable and productive scientist. As you develop the skills to read an article, try to also foster good reading and learning habits for yourself (recommendations here: [ 6 ] and [ 7 ], respectively) and in others. Good luck and happy reading!

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the mentors, teachers, and students who have shaped our thoughts on reading, learning, and what science is all about.

Funding Statement

MAC was supported by the PhRMA Foundation's Postdoctoral Fellowship in Translational Medicine and Therapeutics and the University of Virginia's Engineering-in-Medicine seed grant, and KLS was supported by the NIH T32 Global Biothreats Training Program at the University of Virginia (AI055432). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

- 1. Brown E. The Weird Sisters. G. P. Putnam’s Sons; 2011. [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Kirsch I. Response expectancy theory and application: A decennial review. Appl Prev Psychol. 1997. March 1;6(2):69–79. [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Karanicolas PJ, Farrokhyar F, Bhandari M. Practical tips for surgical research: blinding: who, what, when, why, how? Can J Surg. 2010. October;53(5):345–8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Fiorella L, Mayer RE. The relative benefits of learning by teaching and teaching expectancy. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2013. October 1;38(4):281–8. [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Koh AWL, Lee SC, Lim SWH. The learning benefits of teaching: A retrieval practice hypothesis. Appl Cogn Psychol. 2018. May 15;32(3):401–10. [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Méndez M. Ten simple rules for developing good reading habits during graduate school and beyond. PLoS Comput Biol. 2018. October;14(10):e1006467 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006467 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Erren TC, Slanger TE, Groß JV, Bourne PE, Cullen P. Ten simple rules for lifelong learning, according to Hamming. PLoS Comput Biol. 2015. February;11(2):e1004020 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004020 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (247.8 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Search Utah State University:

Reading and understanding research articles.

- Systematic investigation into a subject to discover or revise facts, theories, and applications.

- Involves the collection, interpretation, and analysis of data.

- Can be qualitative (exploratory) or quantitative (statistical).

- A process where experts in the field evaluate the quality and validity of the research before it’s published.

- Ensures the research methods and results are reliable and credible.

- Identifies any errors or biases.

- Recommends changes or additional experiments to clarify results.

- Abstract : Provides a summary of the entire study.

- Introduction : Presents the research question and background.

- Methods : Describes how the study was conducted.

- Results : Presents the findings of the study.

- Discussion : Interprets the results and links them to other research.

- Conclusion : Summarizes the study and suggests future research directions.

- References : Lists the sources cited in the article.

- Read the abstract, introduction, and conclusion to get a basic understanding, then go back and read the results and methods to get a full picture.

- Look at the data presented in tables, charts, and graphs.

- Interpret the statistical analysis, including p-values, confidence intervals, and effect sizes.

- Consider the context and limitations of the research.

- Check the Source : Evaluate the credibility of the publication or website. Look for reputable sources, authors, or institutions. Talk to your mentor or librarians for help.

- Examine the Author’s Credentials : Check the author’s qualifications and expertise in the field. This can help determine the reliability of the information.

- Assess the Content’s Accuracy : Cross-reference the information with other reliable sources to ensure its accuracy.

- Analyze the Methodology : For research articles, scrutinize the methodology used. Check if the study design is appropriate, the sample size is adequate, and the analysis is correct.

- Evaluate the Objectivity : Determine if the content is biased* or objective. Look for any potential conflicts of interest.

- Review the Citations : Check the references or citations used in the article. They should be from credible and relevant sources.

- Consider the Date of Publication : Ensure the content is up to date. Research published in the last ten years is generally considered current.

- Compare and contrast existing literature: Explore current literature to determine whether existing research supports or contradicts the author’s conclusions.