An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Clinical Trials

For patients.

- Learn About Clinical Research

- Find NIDCR Clinical Trials

- Search All Clinical Trials

For Researchers

- Funding Opportunities

- Documents for Researchers Conducting Human Subjects Research

For Dental Professionals: National Dental Practice-Based Research Network

- Grant Applicants

- Researchers Proposing a Study Idea

- Researchers Preparing a Grant Application

- Funding Opportunity Announcements

- Practitioners / Clinicians

- National Dental Practice-Based Research Network

- Participation in the National Dental PBRN

- National Dental PBRN Website

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

Evidence-Based Dentistry

EBD aims to create a dialogue between dental practitioners and dental researchers, in order to drive new research and promote the use of the best available evidence to inform clinical decision-making.

Effectiveness of behavioural therapy and inhalational sedation in reducing dental anxiety among patients attending dental clinics - a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Greeshma Unnikrishnan

- Abhinav Singh

- Bharathi M. Purohit

What role does antibiotic resistance play in secondary endodontic infections?

- Arunika Nehra

- Melissa Sin

Effectiveness of hand and rotary instrumentations during biomechanical preparation in primary teeth: an umbrella review with evidence stratification

- Arun Kumar Patnana

- Krupal Joshi

- Pravin Kumar

Contemporary Dental Pharmacology: Evidence-Based Considerations

- Nafeesa Hussain

Current issue

Rethinking dental research: the importance of patient-reported outcomes and minimally clinically important difference.

- Giusy Rita Maria La Rosa

Real world evidence: will the “pyramid” of evidence need some redefining…?

- Neeraj Gugnani

Investigating the effectiveness of water fluoridation

- Darshini Ramasubbu

- Jonathan Lewney

- Brett Duane

Effectiveness of nanosilver fluoride in arresting dental caries in children with one- year follow-up – a systematic review

- Pooja J. Shetty

- Prasanna Mithra

- Ambili Nanukuttan

Effectiveness of mineral trioxide aggregate on postoperative pain in non-surgical endodontic treatment: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials

- Maryam Altuhafy

- Vikranth Ravipati

Use of electrical stimulation for accelerated orthodontics in humans: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Shubhobrata Dutta

- Tanisha Rout

- Sonakashee Deshmukh

Announcements

EBD indexed in ESCI

We are excited to announce that EBD is now indexed in the Emerging Sources Citation Index (ESCI) and is due to receive its first Impact Factor in 2025 - watch this space!

Call for Papers: PROMs in Dental Implants

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) are recognised as an important component of clinical research, and are particularly important in dental implant research. This collection aims to bring together the best evidence about PROMs within this field.

Call for Papers: Systematic Reviews

Focusing on key areas of clinical practice, this Collection of Systematic Reviews in dentistry and oral health is OPEN for submissions!

Dental Implants Collection

This Collection highlights the intersection of implantology with key dental specialties as well as showcasing new technical approaches. It also features the BDJ Implant Maintenance special issue.

Evidence-Based Dentistry is a Transformative Journal ; authors can publish using the traditional publishing route OR via immediate gold Open Access.

Our Open Access option complies with funder and institutional requirements .

Advertisement

Browse articles

Did the covid-19 pandemic impact antibiotic prescribing patterns among dentists.

- Akshani Patel

- Satish Kumar

Antibiotics as adjunct to non-surgical periodontal therapy in diabetic patients

- Shipra Gupta

- Yeshwanth Perambudhuru

Reevaluating antibiotic prophylaxis: insights from a network meta-analysis on dry socket and surgical site infections

- Tayebe Rojhanian

- Ahmad Sofi-Mahmudi

- Amin Vahdati

Does adjunctive phototherapy have better outcomes than adjunctive antibiotic therapy for the management of peri-implantitis?

- Jacqueline Fraser

- Vithurran Vijayenthiran

Systemic antimicrobials as an adjunct in the management of periodontitis – which drug is best?

- Ellis Hayes

- Ryan McSorley

Pondering the problem of peri-implant pathology

- Ajay S. Kotecha

- Amelia Nadia Karim

Routine antibiotic prophylaxis and early implant failure: is there a link?

- Mojtaba Mehrabanian

- Hassan Mivehchi

- Mojtaba Dorri

Bone graft substitutes and dental implant stability in immediate implant surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Shanthi Vanka

- Fatima Abul Kasem

A systematic review of the implications of lipocalin-2 expression in periodontal disease

- Diana L. Solís-Suárez

- Saúl E. Cifuentes-Mendiola

- Ana L. García-Hernández

Collections

Antimicrobials in Dentistry

Trending - Altmetric

Does oral Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) premedication in patients with irreversible pulpitis increase the success rate of inferior alveolar nerve block?

Are antibiotics overprescribed for apical periodontitis in dental practice?

What is the science underpinning the prescription of antibiotics in dentistry?

Lithium disilicate, full coverage crowns: what is the effect of using conventional impressions compared to digital impression with respect to the internal fit of the restoration? A systematic review

Dentistry jobs, associate dentist with special interest in ortho/ specialist orthodontist.

We are an independent fully private looking for a Part Time DWSI/Specialist in Orthodontics

Birmingham, Nottingham, Derby, Leicester

Measham Dental

Associate Dental Surgeon

Full clinical freedom, . Experienced support staff. Computerised, digital x-ray, Rotary Endo. free parking. Implant, sedation and Oral surgery exposur

West Midlands Region

Harden Dental Surgery

Associate Dentist

Exciting opportunity for a dentist to join our friendly family-owned business in the affluent village of Tarporley, Cheshire. The successful applic...

Tarporley, Cheshire

Oaklands Dental care

Full-Time/Part-Time Associate - Independent / Private -well-established independently owned six surgery practice

TS19 9JW, Stockton-on-Tees

Roseworth Dental Centre

Join Apolline Dental as an Associate Dentist, taking over a mature list. High private potential, modern tech, friendly and supportive setting

Chingford Green, London (Greater)

Apolline Dental

This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Account Login

Science at the ADA

Innovative research for clinical decision making, critical policy information and oral health care performance measures.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Evidence Based Dental Care: Integrating Clinical Expertise with Systematic Research

Mallika kishore, sunil r panat, ashish aggarwal, nupur agarwal, nitin upadhyay, abhijeet alok.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

NAME, ADDRESS, E-MAIL ID OF THE CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Dr. Mallika Kishore, Post Graduate Student, Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, Institute of Dental Sciences, Bareilly, UP, India. Phone: 09719858806, E-mail: [email protected]

Received 2013 May 31; Revision requested 2013 Nov 24; Accepted 2013 Dec 19; Issue date 2014 Feb.

Clinical dentistry is becoming increasingly complex and our patients more knowledgeable. Evidence-based care is now regarded as the “gold standard” in health care delivery worldwide. The basis of evidence based dentistry is the published reports of research projects. They are, brought together and analyzed systematically in meta analysis, the source for evidence based decisions. Activities in the field of evidence-based dentistry has increased tremendously in the 21 st century, more and more practitioners are joining the train, more education on the subject is being provided to elucidate the knotty areas and there is increasing advocacy for the emergence of the field into a specialty discipline. Evidence-Based Dentistry (EBD), if endorsed by the dental profession, including the research community, may well- influence the extent to which society values dental research. Hence, dental researchers should understand the precepts of EBD, and should also recognize the challenges it presents to the research community to strengthen the available evidence and improve the processes of summarizing the evidence and translating it into practice This paper examines the concept of evidence-based dentistry (EBD), including some of the barriers and will discuss about clinical practice guidelines.

Keywords: Evidence based medicine, Dentistry, Dental care, Dental education

Introduction

The practice of dentistry presents many challenges on a daily basis. Keeping up with new materials and techniques, dealing with the numerous demands of running a small business, and meeting a variety of professional obligations, all compete for our time and attention [ 1 ]. As healthcare providers, it is important that physicians and dentists offer the best possible care for their patients. This requires not only a sound educational base but also a good source of current best evidence to support their treatment recommendations [ 2 ]. To do it successfully, certain skills need to be obliviously acquired, being the intention of evidence-based dentistry the providing better information for the clinician, improved treatment for the patient, and consequently an increased standing of the profession [ 3 ].In many countries, there has been increasing concern about the use of Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) in oral health care [ 4 ].The principles and methods of evidence based dentistry give dentists the opportunity to apply relevant research findings to the care of their patients. The key to finding evidence is to start with a focused, well-built clinical question [ 5 ]. Evidence-based oral health care includes the search for the best evidence, critical evaluation of the evidence, and integration of the evidence with the practitioner’s experience and expertise. Therefore, dental educators, dental students, and dental practitioners need to be aware of the uncertainties surrounding scientific evidence, the ways that the results of clinical studies are collected and analyzed, and the importance of unbiased research on which to base clinical decision making [ 6 ].

A goal of Healthy People 2010 is to promote the oral health of 50% of the nation’s children by applying sealants to their molar teeth. Unfortunately, just 32% of children aged 6 to 19 years have sealants. This may be due to the relatively slow translation of current biomedical science into dental practice [ 7 ].

The need for valid and current information for answering everyday clinical questions is growing. Ironically, the time available to seek the answers seems to be shrinking. In addition, a surprising amount of published research “belongs in the bin”[ 8 ] .

Evidence-based dentistry (EBD) closes the gap between clinical research and real world dental practice and provides dentists with powerful tools to interpret and apply research findings [ 9 ]. In dentistry, the evidence-based movement is at a relatively early stage of development. In addition to collating guidelines on effective care, it is critically important to understand what factors will influence dentists’ ability to change their clinical practices to incorporate the evidence. Without an understanding of how dentists change their clinical practices, evidence-based dentistry will achieve little [ 10 ].Therefore, it is crucial to implement evidence from research into clinical practice, and by doing this, the concept of EBD can become practically relevant to the dentist [ 11 ].

Evidence Based Dentistry

According to Azarpazhooh A et al., Evidence-based practice is a process of lifelong, self-directed learning in which providing health care creates the need for important information about diagnosis, prognosis, treatment, and other clinical and health care issues [ 12 ]. The American Dental Association’s definition is by far the most comprehensive, as it captures the core elements of EBD. They define it as “an approach to oral health care that requires the judicious integration of systematic assessments of clinically relevant scientific evidence, relating to the patient’s oral and medical condition and history, with the dentist’s clinical expertise and the patient’s treatment needs and preferences” [ 13 ]. It is a widely accepted term in the medical fields around the world. It can be defined as “the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients”[ 14 ].

Evidence-based practice (EBP) is said to be the current best approach to provide interventions that are scientific, safe, efficient and cost effective. The reasons for this are assumed to be through improvements in physicians’ and dentists’ skills and knowledge, as well as in the communication between patients and their physicians about the rationale behind clinical recommendations made. While studies have attempted to assess the levels of awareness and implementation of EBD amongst various groups of clinicians in different settings, it is not possible to generalize the results to all clinicians [ 2 , 15 ]. Evidence is based on the existence of at least one well-conducted randomized control trial (RCT) [ 16 ]. When asked about evidence-based practice, general dentists have a problem with the words themselves. The word “base” conjures an image of fundamental change. It implies a change in an essential entity, a foundation, something the practitioner cannot do without. The word “evidence” also causes a problem, because it has not been part of the vocabulary of clinical practice. It may conjure fear, because it relates to legal and regulatory matters. Evidence is what lawyers bring before a judge and jury in the pursuit of truth and justice [ 17 ].

Concept of Evidence Based Dentistry

In understanding the concept of EBD, it is helpful to clarify what it is not. It is not a “cookbook” approach to practice. EBD requires the integration of the best evidence with clinical expertise and patient preferences and, therefore, it informs, but never replaces, clinical judgement. Evidence-based health care recognizes the complex environment in which clinical decisions are made and the importance of individual patient circumstances, beliefs, attitudes and values[ 17 ]. Evidence-based practice is a practical approach to clinical problems. It involves tracking down the best available evidence, assessing its validity and using “rules of evidence” to grade the evidence according to its strength [ 18 ].

Evidence based dentistry does not mean clinicians abandon everything they learned in dental school. It does not force clinicians to go backwards to justify things the profession universally accepts [ 19 ].

Goals of Evidence Based Dentistry

Evidence-based dentistry has two main goals: best evidence/research, and the transfer of this in practical use. This involves four basic phases: Asking evidence-based questions (framing an answerable question from a clinical problem); Searching for the best evidence; Reviewing and critically appraising the evidence; Applying this information in a way to help the clinical practice [ 20 ]. An additional phase has been suggested that is the evaluation of performance of the techniques, procedures or materials [ 21 ].Evidence-based practice involves tracking down the available evidence, assessing its validity and then using the “best” evidence to inform decisions regarding care. Rules of evidence have been established to grade evidence according to its strength [ 5 ].

Steps in Practising Evidence Based Dentistry

In traditional dental care, emphasis is placed on the dentist’s accumulated knowledge and experience, adherence to accepted standards, and the opinion of experts and peers. Evidence-based practice, in contrast, places a premium on using current evidence to solve clinical questions [ 22 ].It presupposes two things about the dentist: one, that he or she is conversant with the current literature, and two, that he or she is competent to evaluate it. The first requires that dentists read the scientific literature, particularly in clinical research, and the second requires that they can critically appraise the literature. Niederman and Badovinac [ 23 ] identify five steps in clinical decision making that the evidence-based dentist must be involved in:

1) Converting clinical information needs into an answerable question

2) Using electronic databases to find available evidence

3) Critically appraising the evidence for validity and importance

4) Integrating the appraisal with the patient’s perceived needs and applying these results in clinical practice

5) Evaluating their own performance

Awareness of Evidence Based Dentistry Among the Dentists

There have been various studies performed to study the awareness of dentists regarding the evidence based dentistry. In a study done in Kuwait it was concluded that the overall awareness of EBD amongst dentists was low, even though more than half of them reported that they generally practise it [ 2 ].

Similar study carried out among the general dental practitioners currently practising in the North West of England and it was found that only 29% (60/204) could correctly define the term EBP. When faced with clinical uncertainties 60% (122/204) of general dental practitioners turned to friends and colleagues for help and advice. Eighty one percent of respondents were interested in finding out further information about EBP (165/204) [ 9 ].

Other studies carried out to evaluate evidence-Based Practice among a group of Malaysian Dental Practitioners and response rate was 50.3 percent [ 14 ].

Clinical Practice Guidelines

Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) are “systematically developed statements to assist practitioners and patients in arriving at decisions on appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances.”[ 1 ].

Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (EB-CPGs) are structured and formal, and use rigorous, explicit and reproducible methods to assemble and evaluate the evidence. These guidelines are based on systematic reviews and incorporate values and preferences of patients and practitioners. The process of creating a well-developed EB-CPG includes external review and comment by those who will be using the guidelines - for example, a wide range of clinicians, as well as patients or their representatives [ 24 ].

The development of EB-CPGs in dentistry is in the beginning stages. A review in 1995 of guideline development by various dental organizations and specialties in the United States revealed a lack of systematic analysis of the literature.

Implementing Evidenced Based Dentistry in Clinical Practise

Learning involves identifying and evaluating new methods that might improve care and prognosis, determining when to implement those that appear to improve care, and discarding old diagnostics and therapeutics that prove to be unsound [ 25 ]. In this information age, it is not uncommon for a patient to rush home from the dentist’s office to look up on the Internet or in health reference texts the drug or diagnosis that was provided. Science in the form of statistical evidence is being introduced into everyday language through advertising [ 16 ]. However, some studies have demonstrated that EBD, when taught only in the classroom, may have little impact on the attitudes or behaviors of clinical practitioners. In other words, theoretical knowledge of EBD, obtained without opportunities to practice using an evidence-based approach to patient care decision making, may lead to no changes in dental practice at all. Therefore, it is crucial to implement evidence from research into clinical practice, and by doing this, the concept of EBD can become practi¬cally relevant to the dentistry [ 11 ].

Although considerable resources are spent on clinical research, little attention has been paid to the implementation of research evidence into clinical care [ 10 ]. EBP may not be a concept that every dentist is familiar with, but increasing consumer pressures and the present economic, social, and political changes, will necessarily demand that evidence based principles are implemented [ 9 ].

Searching For the Best Evidence

Practitioners can access computerize bibliographic database such as MEDLINE for references either online via the Internet or in a CD-ROM format [ 26 ]. Below are some essential online resources for evidence based research.

PubMed is a free medical database provided by the U.S. National Library of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health (NLM). Highly authoritative and up-to-date, PubMed gives you access to MEDLINE, NLM’s database of citations and abstracts in the fields of medicine, nursing, dentistry, veterinary medicine, health care systems and preclinical sciences. Updated daily, Pub Med gives you access to over 14 million citations dating back to the 1950s. Records are indexed using the NLM’s Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) [ 13 ].

The Cochrane Collaboration

The Cochrane Collaboration is an international organization whose overall aim is to b;uild and maintain a database of up-to-date systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials of health care and to make these readily accessible electronically. It has been called “an enterprise that rivals the Human Genome Project in its potential implications for modern medicine” [ 27 ] and has also been described as being one of the most significant clinical advances since the creation of the National Institutes of Health in the U.S [ 13 ].

Barriers to Implementing Evidence-Based Clinical Practise

In many countries, there has been increasing concern about the use of evidence-based practice (EBP) in oral health care. The call for the implementation of EBP to increase the effectiveness of dental care seems to face many obstacles [ 4 ].

Potential Barriers to Change

1) Environmental: a) In the practice: There are limitations of time and organisation of the practice (for example, a lack of disease registers or mechanisms to monitor repeat prescribing).

b) In education: Due to inappropriate continuing education and failure to connect with program to promote better quality of life. There is lack of incentives to participate in effective educational activities.

c) In health care: Due to lack of financial resources and defined practice populations. Ineffective or unproved activities promoted by health policies. Failure to provide practitioners with access to appropriate information.

d) In society : Due to influence of the media on patients in creating demands or beliefs. There is impact of disadvantage on patients’ access to care.

2) Personal

a) Factors associated with the practitioner

Due to obsolete knowledge and influence of opinion leaders (such as health professionals whose views influence their peers) along with beliefs and attitudes (for example, a previous adverse experience of innovation).

b) Factors associated with the patient

There are demands for care by the patient and perceptions or cultural beliefs about appropriate care [ 28 ].

A qualitative study was carried out to assess the obstacles among the Flemish (Belgian, Dutch-speaking) dentists experience in the implementation of EBP in routine clinical work. Three major categories of obstacles were identified. These categories relate to obstacles in

1) Evidence,

2) Partners in health care (medical doctors, patients, and government),

3) Field of dentistry.

Their findings suggested that educators should provide communication skills to aid decision making, address the technical dimensions of dentistry, promote lifelong learning, and close the gap between academics and general practitioners (dentists) in order to create mutual understanding [ 4 ].

The most common barriers to implementation of early-adopting dentists are difficulty in changing current practice model, resistance and criticism from colleagues, and lack of trust in evidence or research [ 7 ].

In an article noted that “dentistry is stunningly inexact science.” It is therefore becoming increasingly clear in this “age of Information” that investigative journalism and consumer activism render all clinical decision-making subject to external scrutiny rather than to just professional or peer-review as in the past [ 29 ].

Current Status of Clinically Relevant Evidence in Dentistry

The translation of research into practice assumes that clinically relevant evidence is available. Unfortunately, in light of the billions of dollars invested in dental research during the last five decades in Europe and the US, the dental research community has paid relatively little attention to clinical aspects of care. Consequently, and contrary to the situation in medicine, there are relatively few randomized controlled trials and other outcomes oriented studies in dentistry that have evaluated clinically relevant interventions. For example, there are no clinical trials that have compared the outcomes of different methods of caries diagnosis using relevant outcome measures. Also, no outcome studies are available for disease-based management of dental caries, periodontal diseases, or facial pain [ 30 ].

The evidence needed for evidence-based dentistry must include a broader range of outcomes, including those considered important by patients. For example, a classic definition of appropriateness indicates that treatment is deemed appropriate when the expected health benefit exceeds the expected negative consequences by a sufficiently wide margin that the treatment is worth doing [ 31 ].

Benefits of Evidence Based Practise

There are some advantages of evidence based practice [ 32 ] [ Table/Fig-1 ].

[Table/Fig-1]:

Advantages of evidence based dental practise

Evidence-based dentistry does offer the opportunity for the practice of dentistry to enter a new era, it is worth recalling an old maxim— “the trouble with opportunity is it always comes disguised as hard work.” Educators have an important role to play in providing communication skills to aid decision making, addressing the technical dimensions of dentistry, promoting lifelong learning, and closing the gap between academics and general dentists in order to create mutual understanding The ultimate goal would be assisting dental students in learning the skills to practice evidence-based dentistry so that they can provide their future patients with the best clinical evidence and judgment for optimal and cost-effective dental care. There is, therefore, a need to apprise current practitioners on the new method of thinking. Dentistry needs to make strides to keep pace with the prevailing paradigm of evidence-based care. There is a strong “need for the science behind our treatment decisions”.

Financial or Other Competing Interests

- [1]. Sutherland SE. The building blocks of evidence-based dentistry. J Can Dent Assoc. 2000;66:241–4. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [2]. Haron IM, Sabti MY, Omar R. Awareness, knowledge and practice of evidence-based dentistry amongst dentists in Kuwait. Eur J Dent Educ. 2012;16:e47–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2010.00673.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [3]. Ballini A, Capodiferro S, Toia M, Cantore S, Favia G, De Frenza G, et al. Evidence-based dentistry: what’s new? Int J Med Sci. 2007;4:174–8. doi: 10.7150/ijms.4.174. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [4]. Hannes K, Norré D, Goedhuys J, Naert I, Aertgeerts B. Obstacles to implementing evidence-based dentistry: a focus group-based study. J Dent Educ. 2008;72:736–44. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [5]. Sutherland SE. Evidence-based dentistry: Part IV. Research design and levels of evidence. J Can Dent Assoc. 2001;67:375–8. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [6]. Crawford JM, Briggs CL, Engeland CG. Publication bias and its implications for evidence-based clinical decision making. J Dent Educ. 2010;74:593–600. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [7]. Spallek H, Song M, Polk DE, Bekhuis T, Frantsve-Hawley J, Aravamudhan K. Barriers to implementing evidence-based clinical guidelines: a survey of early adopters. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2010;10:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2010.05.013. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [8]. Sutherland SE. Evidence-based dentistry: Part V. Critical appraisal of the dental literature: papers about therapy. J Can Dent Assoc. 2001;67:442–5. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [9]. Iqbal A, Glenny AM. General dental practitioners’ knowledge of and attitudes towards evidence based practice. Br Dent J. 2002;193:587–91. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4801634. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [10]. McGlone P, Watt R, Sheiham A. Evidence-based dentistry: an overview of the challenges in changing professional practice. Br Dent J. 2001;190:636–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4801062. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [11]. Faggion CM Jr, Tu YK. Evidence-based dentistry: a model for clinical practice. J Dent Educ. 2007;7:825–31. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [12]. Azarpazhooh A, Mayhall JT, Leake JL. Introducing dental students to evidence-based decisions in dental care. J Dent Educ. 2008;72:87–109. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [13]. Rabb-Waytowich D. You ask, we answer:Evidence-based dentistry: Part 1. an overview. J Can Dent Assoc. 2009;75:27–8. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [14]. Yusof ZY, Han LJ, San PP, Ramli AS. Evidence-based practice among a group of Malaysian dental practitioners. J Dent Educ. 2008;72:1333–42. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [15]. Haj-Ali RN, Walker MP, Petrie CS, Williams K, Strain T. Utilization of evidence-based informational resources for clinical decisions related to posterior composite restorations. J Dent Educ. 2005;69:1251–6. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [16]. Beyers RM. Evidence-based dentistry: a general practitioner’s perspective. J Can Dent Assoc. 1999;65:620–2. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [17]. Browman GP. Evidence-based paradigms and opinions in clinical management and cancer research. Semin Oncol. 1999;26:9–13. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [18]. Sackett DL. Rules of evidence and clinical recommendations for the management of patients. Can J Cardiol. 1993;9:487–9. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [19]. Goldstein GR. What is evidence based dentistry? Dent Clin North Am. 2002;46(1-9):v. doi: 10.1016/s0011-8532(03)00044-2. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [20]. Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996;312:71–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [21]. Carr AB, McGivney GP. Users’ guides to the dental literature: how to get started. J Prosthet Dent. 2000;83:13–20. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [22]. Coulter ID. Evidence-based dentistry and health services research: is one possible without the other? J Dent Educ. 2001;65:714–24. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [23]. Niederman R, Badovinac R. Tradition-based dental care and evidence-based dental care. J Dent Res. 1999;78:1288–91. doi: 10.1177/00220345990780070101. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [24]. Jadad A. Randomized controlled trials. London: BMJ Books; 1998. From individual trials to groups of trials: reviews, meta-analyses and guidelines; pp. 78–92. [ Google Scholar ]

- [25]. Marinho VC, Richards D, Niederman R. Variation, certainty, evidence, and change in dental education: employing evidence-based dentistry in dental education. J Dent Educ. 2001;65:449–55. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [26]. Nainar SM. Evidence-based dental care-a concept review. Pediatr Dent. 1998;20:418–21. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [27]. Naylor CD. Grey zones of clinical practice: some limits to evidence-based medicine. Lancet. 1995;345:840–2. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92969-x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [28]. Haines A, Donald A. Making better use of research findings. BMJ. 1998;317:72–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7150.72. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [29]. Ecenbarger W. How honest are dentists? Reader’s Digest. February, 1997;150:50–56. [ Google Scholar ]

- [30]. Dickersin K, Manheimer E. The cochrane collaboration: evaluation of health care and services using systematic reviews of the results of randomized controlled trials. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1998;41:315–31. doi: 10.1097/00003081-199806000-00012. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [31]. Bader J, Ismali A, Clarkson J. Evidence-based dentistry and the dental research community. J Dent Res. 1999;78:1480–3. doi: 10.1177/00220345990780090101. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [32]. Merijohn GK, Bader JD, Frantsve-Hawley J, Aravamudhan K. Clinical decision support chairside tools for evidence-based dental practice. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2008;8:119. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2008.05.016. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (90.8 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

- Open access

- Published: 23 May 2023

Quality of survey-based study reports in dentistry

- Manuel Antonio Mattos-Vela 1 ,

- Teresa Angélica Evaristo-Chiyong 1 &

- Kariem Siquero-Vera 1

BMC Oral Health volume 23 , Article number: 320 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

1479 Accesses

Metrics details

Surveys are a widely used research method in dentistry in different specialities. The study aimed to determine the quality of survey-based research reports published in dentistry journals from 2015 to 2019.

A cross-sectional descriptive research study was conducted. The report quality assessment was carried out through the SURGE guideline modified by Turk et al. Four journals indexed in the Web of Science were selected: BMC Oral Health, American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, Journal of Dental Education, and Journal of Applied Oral Science. The selection of articles was made using the PubMed database considering the following search words: questionnaire OR survey, two trained reviewers applied the guideline to the selected articles, and the controversies were solved by discussion and consensus.

A total of 881 articles were identified, of which 99 met the selection criteria and were included in the study. The best-reported items (n = 99) were four: the two that described the introduction of a study, the results reflecting and concerning the study objectives, and the review by an ethics committee. Five items were poorly reported: to declare the incentives to study participants (n = 93), three items on the description of statistical analyses (n = 99, 99, and 94), and information on how nonrespondents differed from respondents (n = 92).

Conclusions

There is a moderate quality of reporting of all aspects that should be considered in survey-based studies in dentistry journals. Poorly reported criteria were found mainly in the statistical analysis.

Peer Review reports

Surveys are a widely used research method in dentistry in its different specialities, but mostly in public health, ethics, and education [ 1 , 2 ]. This method can be applied in quantitative, qualitative, or mixed research; it allows for collecting information on a specific topic through low-cost questionnaires that are easy to apply [ 3 , 4 ].

Research studies using surveys are as important as any other type of research; they are the beginning of exploratory studies, as well as cross-sectional axes in quantitative research. They are the basis for going on to the next levels of evidence, thus allowing for a comprehensive approach to health research, being used to address issues that are difficult to evaluate and allowing the generation of constructs in a specific topic [ 5 , 6 ].

In a study conducted by Bennett et al. [ 5 ] on the evaluation of the quality of survey reports in the medical field, in 117 published studies, it was found that several criteria were poorly reported: few studies provided the survey or core questions (35%), reported the validity or reliability of the instrument (19%), defined the response rate (25%), discussed the representativeness of the sample (11%) or identified how they handled missing data (11%). Other studies evaluating the quality of survey-based study reports found similar results, e.g., Turk et al. [ 6 ] in different medical disciplines, Li et al. [ 7 ] in the area of nephrology, Pagano et al. [ 8 ] in the area of transfusion medicine, and Rybakov et al. [ 9 ] in the area of pharmacy. However, no studies were found evaluating the quality of survey reports in dentistry.

Science grows with the production of scientific knowledge informed through research articles, which should allow for evaluating the quality of the study conducted. It is necessary to know how much of the survey-based dentistry research published in high- and medium-impact journals is useful and has been clearly and completely reported. It is necessary to identify where it is failing and what needs to be improved so that these reports are useful for the profession, systematic reviews, and science. The study aimed to determine the quality of survey-based research reports published in dentistry journals from 2015 to 2019.

Type of study

A descriptive, cross-sectional investigation was carried out.

The study was approved at the institutional level, and evaluation by a research ethics committee was not considered necessary because it was a documentary evaluation that did not include human subjects.

Population and sample

Articles published from 2015 to 2019 in four dentistry journals indexed on the Web of Science. The following journals were selected: BMC Oral Health, American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, Journal of Dental Education, and Journal of Applied Oral Science because they are high- and medium-impact journals (Q1 and Q2) that mostly publish survey-based articles, which was determined by reviewing a pilot sample of 140 articles published in dentistry journals during 2019, found in the PubMed database and based on surveys. A 5-year time period was considered for the search for articles based on previous studies that used a variable time range, between 1 and 17 years [ 6 , 8 , 9 ].

Inclusion criteria

original survey studies that used a self-administered questionnaire as the primary research instrument (to answer its primary objective), cross-sectional surveys, and studies published in English.

Exclusion criteria

studies for the validation of an instrument that examined only the psychometric characteristics of the instrument, surveys administered through the web (online), study designs (randomized clinical trials, cohort studies, and case-control studies) where surveys were only used for demographic data, other types of studies (reviews, letters, commentaries, etc. ), studies that were part of a larger investigation, studies that performed a secondary analysis of the survey, studies that used semistructured interviews instead of questionnaires and surveys sent by e-mail.

Article selection procedure

This study defines a survey as the research method by which information is collected by asking people written questions about a specific topic, and the data collection procedure is standardized and well-defined [ 3 ].

The PubMed database was used to select the articles for each of the selected journals using the following search words: questionnaire OR survey, filtering by publication date from January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2019.

Two reviewers independently selected all references (title and abstract) and excluded those that did not meet the established criteria. In the second stage, the full-text articles were reviewed to determine which would be included in the study. In both stages, after the independent review, the researchers compared their results, and in cases of discrepancy, these were discussed and agreed upon.

Criteria for evaluating the quality of the report

The quality of the articles was evaluated independently and in duplicate by two other reviewers. Disputes were resolved by discussion and consensus.

To evaluate the quality of the research reports, the SURGE instrument modified by Turk et al. [ 6 ] was chosen, containing 33 items, of which only one item was modified, and the telephone survey mode, which was eliminated since only self-administered questionnaires were evaluated. This instrument was tested by two researchers on a convenience sample of survey items identified by the authors. No modifications had to be made to the content or wording.

The following variables were also recorded to characterize the sample: year of publication, continent of origin and journal.

Pilot study

A pilot study was conducted to train and standardize criteria for the search and selection of the articles, according to the established selection criteria, as well as for the application of the quality criteria of the report.

Statistical analysis

Data processing and analysis were carried out using the statistical program SPSS v 26 (SPSS Inc., IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were applied to the study variables using frequency distribution tables.

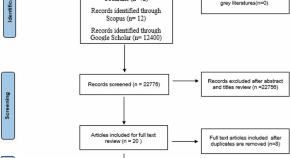

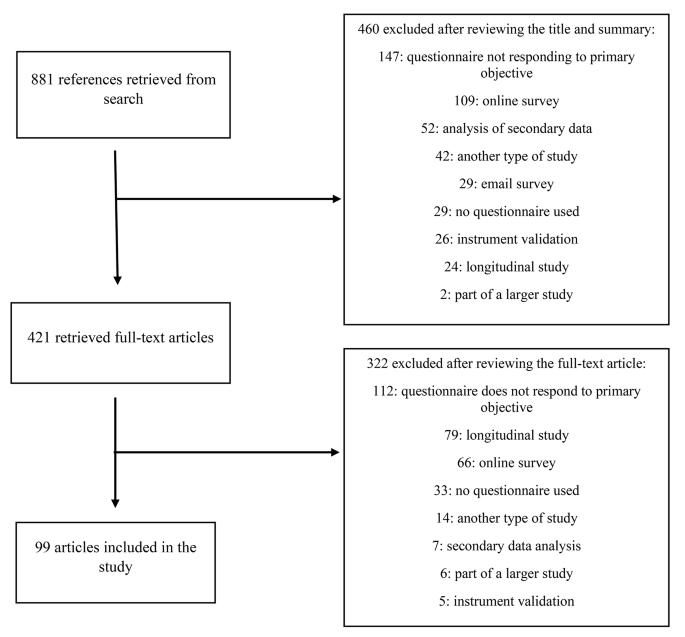

From the bibliographic search, 881 references were retrieved; then, their titles and abstracts were read, and 460 were excluded according to the established criteria. From the other references, the full text of the articles (n = 421) was obtained and evaluated to determine compliance with the selection criteria, excluding 322 articles and considering only 99 in the study to apply the SURGE guidelines and evaluate the quality of the report (Fig. 1 ). In the study sample, the most frequent articles were those published in 2018 (n = 29), those from the Americas (n = 41), and those published in the journal BMC Oral Health (n = 43) (Table 1 ). The percentage value is not mentioned in all results because it matches the absolute value.

Flowchart of selected articles for the study

Table 2 shows the evaluation results of the title, abstract, introduction, and methods of the articles through 21 criteria of the SURGE instrument.

It was found that most articles used the term survey or questionnaire in the title or abstract (n = 97). All articles explained why the research was necessary and indicated the study objective.

In the section on methods, almost half of the articles provided the questionnaire (n = 45) and used an existing instrument (n = 50). In this case, 32 did not mention their psychometric properties, and three did not provide references to the original work. Among the papers that used a new instrument (n = 49), 23 did not mention the procedures used to develop it or the methods used for the pretest, while 36 did not report the validity and confidence of the instrument. Among the studies that used a questionnaire that required scoring (n = 83), six did not describe the scoring procedures.

Regarding the evaluation of the sample selection, few studies did not describe the study population and the sample framework (n = 24), the representativeness of the sample (n = 12), the calculation of the sample size, or the justification thereof (n = 18).

Regarding survey administration, few articles mentioned the mode of administration or the type and number of contacts (n = 13); however, most of them did not report the incentives to respondents (n = 93) or who approached potential participants (n = 61).

In the evaluation of the statistical analysis, four articles did not describe the method of analysis, while none reported the methods for the analysis of the nonresponse error and the calculation of the response rate; most failed to mention definitions for complete versus partial endings (n = 62) and methods for handling missing data (n = 94).

Table 3 describes the evaluation of the results, discussion, and ethical aspects of the articles through 12 criteria of the SURGE instrument.

In the results section, 24 articles did not report the response rate, 13 did not consider all respondents, and 92 did not report the difference between respondents and nonrespondents. However, in all the articles, the results were presented clearly and in relation to the study objectives.

For the Discussion section, only one criterion was correctly reported in all cases, and the results were summarized in relation to the study objectives, while 46 and six articles did not mention the strengths and limitations of the study, respectively. In addition, 34 studies discussed the generalization of results.

Finally, regarding ethical quality indicators, all articles reported on the review of the study by an ethics committee, while 57 and 27 articles did not report on the funding and procedures of respondent consent, respectively.

In the evaluation of the quality of survey-based studies, it was found that the best-reported sections were title and abstract, introduction, sample selection, results, and discussion; specifically, there were 15 criteria very well reported (with a frequency greater than 80%), most of them within the aforementioned sections. Bennett et al. [ 5 ], Pagano et al. [ 8 ], and Rybakov et al. [ 9 ] also found the title and abstract, introduction, and discussion sections well reported. It is possible that the STROBE [ 10 ] guidelines, which are the guidelines for good reporting of observational studies required by health science journals, may have contributed to this. In addition, the recommendations given for writing the items in these sections are well-known and easy to comply with.

There are 12 criteria where most articles performed a bad report, and five of them were poorly reported (with a frequency greater than 80%): incentives to study participants; mentioning methods for nonresponse error analysis, calculating the response rate, and handling missing item data; and reporting how nonrespondents differed from respondents. Three of these criteria belong to the analysis section. Other investigations found a greater number of misreported criteria [ 5 , 6 , 8 ]; one even observed as many as 21 inadequately reported items in medical articles [ 5 ]. The items mentioned methods for nonresponse error analysis [ 5 , 6 , 8 , 9 ] and for handling missing item data [ 5 , 8 , 9 ] were also poorly reported in other research studies.

This research allows warning about the aspects that should be improved in the reporting of studies based on self-administered surveys in the field of dentistry. In the Methods section, it should be emphasized that when the research is conducted using a new or existing questionnaire, the psychometric properties of the questionnaire should be mentioned. The vast majority of researchers in the studies evaluated considered it sufficient to mention only the reference to the original validation work when working with an existing questionnaire.

The SURGE guidelines [ 11 ], unlike STROBE [ 10 ], develop more precisely what needs to be reported in terms of the survey administration. This research has demonstrated that three out of the four items that should be described on this aspect, according to the SURGE criteria, were not performed correctly, which does not allow a study to be replicable or a reader or reviewer to assess its quality and the possible introduction of bias.

The statistical analysis description is a critical aspect in the communication of this research and it is necessary to train researchers in this field since statistical knowledge is an important element to prevent his or her study from lacking methodological validity. This study found that four out of the five items that SURGE recommends reporting in this area were poorly reported, which agrees with other investigations in which the quality of survey-based studies in areas such as general medicine [ 5 , 6 ], transfusion medicine [ 8 ], and pharmacy [ 9 ] were evaluated. A previous study noted the poor reporting of statistical aspects in articles of different research designs in dentistry journals [ 12 ]. Although it is common for articles to report the value of response rate, no one mentioned the method for calculating it; SURGE asks to mention both in the results and methods sections, respectively.

It is also important to note that the description of how nonrespondents differ from respondents should be improved in the results section. It may be infrequent to mention this aspect because of the additional work it would take researchers to obtain this information, as it can be difficult to obtain because of the lack of access to the group of non-respondents. However, where possible, the researcher should report it, which will help to make transparent the representativeness of the sample studied in relation to the population.

Regarding the ethical aspects of a research study, improved reporting of the study’s financing is necessary. It would be advisable for journals to require authors to submit their manuscripts with this information. For example, one of the journals evaluated in this study, BMC Oral Health, provided the communication of ethical aspects since, at the end of the article, they presented sections where the authors had to declare the financing of the study, the approval of an ethics committee, and the consent of participants.

As far as the authors are aware, this is the first study that evaluates the quality of survey-based research in the area of dentistry, which warns of the aspects that should be improved for clearer, more complete, and transparent communication of this type of study, considering that the use of surveys in research in the area of health sciences is frequent [ 1 ].

One limitation of this study was that the evaluation of some quality items was not simple, and the agreement reached by the two evaluators of the article could be different from what was interpreted and evaluated in other studies that also used the SURGE criteria [ 5 , 6 , 8 , 9 ]. For example, in some of the items evaluated, the report was considered valid even though the information was not found in the corresponding section; it was sufficient that it was present somewhere in the article. Moreover, several articles evaluated used nonprobabilistic samples, so the sampling frame was not reported since it was unnecessary. In these cases, this item was not considered misreported. There is no extended version of SURGE where the criteria for evaluating each item are explained in detail, as there is for the STROBE [ 13 ] and CONSORT [ 14 ] statements, among others.

The results of this study are not necessarily generalizable to articles published in all dentistry journals since it only evaluated four journals; however, it is the first report that provides evidence in this field.

It is concluded that there is a moderate quality of reporting of all the aspects to be considered for studies based on self-administered surveys in four dentistry journals. Poorly reported criteria were found mainly in the statistical analysis section.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available in the Zenodo repository, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7391366 .

LaVange LM, Koch GG, Schwartz TA. Applying simple survey methods to clinical trials data. Statist Med. 2001;20:2609–23.

Article Google Scholar

Duran D, Monsalves MJ, Aubert J, Zarate V, Espinoza I. Systematic review of latin american national oral health surveys in adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2018;46(4):328–35.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Ponto J. Understanding and evaluating survey research. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2015;6(2):168–71.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kelley K, Clark B, Brown V, Sitzia J. Good practice in the conduct and reporting of survey research. Int J quality in Health Core. 2003;15(3):261–6.

Bennett C, Khangura S, Brehaut JC, Graham ID, Moher D, Potter BK, et al. Reporting guidelines for survey research: an analysis of published guidance and reporting practices. PLoS Med. 2011;8(8):e1001069.

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Turk T, Elhady MT, Rashed S, Abdelkhalek M, Nasef SA, Khallaf et al. Quality of reporting web-based and non-web-based survey studies: What authors, reviewers and consumers should consider. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0194239.

Li AH, Thomas SM, Farag A, Duffett M, Garg AX, Naylor KL. Quality of survey reporting in nephrology journals: a methodologic review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(12):2089–94.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Pagano MB, Dunbar NM, Tinmouth A, Apelseth TO, Lozano M, Cohn CS, et al. A methodological review of the quality of reporting of surveys in transfusion medicine. Transfusion. 2018;58(11):2720–27.

Rybakov KN, Beckett R, Dilley I, Sheehan AH. Reporting quality of survey research articles published in the pharmacy literature. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2020;16(10):1354–8.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, STROBE Initiative. The strengthening the reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344–9.

Grimshaw J. SURGE (the SUrvey Reporting GuidelinE). In: Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, et al. editors. Guidelines for reporting health research: a user`s manual. Oxford: Wiley; 2014. pp. 206–13.

Google Scholar

Vähänikkilä H, Tjäderhane L, Nieminen P. The statistical reporting quality of articles published in 2010 in five dental journals. Acta Odontol Scand. 2015;73(1):76–80.

Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Mulrow CD, Pocock SJ, et al. STROBE Initiative. Strengthening the reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2007;4(10):e297.

Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gøtzsche PC, Devereaux PJ, et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c869.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not aplicable.

This work was supported by the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos under Grant A20051931.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Facultad de Odontología, Grupo de investigación SAETA, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Calle Germán Amézaga 375. Lima 1, Lima, Peru

Manuel Antonio Mattos-Vela, Teresa Angélica Evaristo-Chiyong & Kariem Siquero-Vera

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

MAM-V: Conception and design of the study, Data acquisition, Data análisis, Discussion of the results, Drafting of the manuscript. TAE-Ch: Conception and design of the study, Data acquisition, Discussion of the results, Drafting of the manuscript. KS-V: Conception and design of the study, Data acquisition, Discussion of the results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Manuel Antonio Mattos-Vela .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Mattos-Vela, M.A., Evaristo-Chiyong, T.A. & Siquero-Vera, K. Quality of survey-based study reports in dentistry. BMC Oral Health 23 , 320 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-023-02979-z

Download citation

Received : 05 December 2022

Accepted : 19 April 2023

Published : 23 May 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-023-02979-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Surveys and questionnaires

- Dental health surveys

- Epidemiologic studies

- Health surveys

BMC Oral Health

ISSN: 1472-6831

- General enquiries: [email protected]

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Bone graft substitutes and dental implant stability in immediate implant surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Shanthi Vanka. Fatima Abul Kasem. Amit Vanka. Research 11 Nov 2024 Evidence ...

Find NIDCR Clinical Trials. Search All Clinical Trials. For Researchers. Funding Opportunities. Documents for Researchers Conducting Human Subjects Research. For Dental Professionals: National Dental Practice-Based Research Network. Grant Applicants. Researchers Proposing a Study Idea. Researchers Preparing a Grant Application.

Research studies in Endodontic and Restorative dentistry are two dimensional. The first dimension is the laboratory research, which provides the best evidence on material science and the second dimension is clinical research, which provides the best evidence in dealing with the burden of illness, with efficient clinical practice.

Journal of Dental Research (JDR) is a peer-reviewed scientific journal dedicated to the dissemination of new knowledge and information, encompassing all areas of clinical research in the dental, oral and craniofacial sciences. Average time … | View full journal description. This journal is a member of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE).

The National Institute of Dental Research was established in the USA: ... Biochemical developments in dental research. Recently, biochemical studies have become an area of increasing importance in dental research, from dental pulp stem cells to synovial fluid analyses, in order to understand the etiology and pathology of temporomandibular joint ...

Read the latest Research articles in Dentistry from Scientific Reports. ... Comparative study of axial displacement in digital and conventional implant prosthetic components.

Bridging the gap between research and dental practice, EBD provides a source of ground breaking issues in Dentistry. With evidence from a wide range of sources, presenting clear, comprehensive and ...

Innovative research for clinical decision making, critical policy information and oral health care performance measures. Stay on top of research ADASRI publishes for the dental industry. View short videos explaining ADASRI's latest research. Take a deep dive into the latest science on a range of subjects, from antibiotics to whitening.

Abstract. Clinical dentistry is becoming increasingly complex and our patients more knowledgeable. Evidence-based care is now regarded as the "gold standard" in health care delivery worldwide. The basis of evidence based dentistry is the published reports of research projects. They are, brought together and analyzed systematically in meta ...

Background Surveys are a widely used research method in dentistry in different specialities. The study aimed to determine the quality of survey-based research reports published in dentistry journals from 2015 to 2019. Methods A cross-sectional descriptive research study was conducted. The report quality assessment was carried out through the SURGE guideline modified by Turk et al. Four ...