- Join our email list

- Post an article

How can we help you?

The anatomy of a case study in instructional design for online learning.

Crafting A Case Study For Online Learning

Imagine you're tasked with designing an online learning module for a mid-sized university. You know that real-world scenarios can be a powerful teaching tool, so you create a case study that engages students and aligns with the principles of heutagogy, emphasizing self-directed learning. Crafting a case study requires a balance of academic rigor and practical application. Let's look at an example of a case study, then explore the anatomy of a compelling case study and its intersection with heutagogical principles. Finally, I will provide a blueprint for bringing your vision to life.

An Example Case Study

Implementing a new learning management system (lms) in a mid-sized university.

A significant transition is underway in a mid-sized university with around 10,000 students and 500 faculty members. As part of a broader digital transformation initiative, the university is moving from an outdated Learning Management System (LMS) to a modern, versatile system.

This change aims to enhance the university's online learning capabilities and digital infrastructure. The transition involves critical stakeholders, including the university administration, the IT department, faculty members, students, and external LMS vendors.

Context And Need For Change

The current LMS is no longer meeting the university's needs. It lacks integration capabilities, poor mobile accessibility, and a user-unfriendly interface. These issues have led to widespread frustration among users and inefficiencies in course delivery. The university's administration recognizes the urgency of addressing these problems to provide a better learning and teaching experience.

Data-Driven Insights

To understand the scope of the problem, the university gathered quantitative and qualitative data. Quantitative data was collected through user satisfaction surveys, system performance metrics, and cost analysis. These metrics highlighted significant gaps in the current system's performance. Additionally, qualitative data from interviews with faculty and students, focus groups, and IT department reports provided more profound insights into user experiences and expectations.

Stakeholder Analysis And Needs

Learners analyzing this data considered the perspectives of various stakeholders:

- Faculty members They need an LMS that supports easy content creation and management.

- Students They demand mobile access to course materials and seamless user experiences.

- IT department They require a system that integrates well with existing infrastructure and ensures data security and stability.

Solution Options

After thorough analysis, three main solution options emerged:

- Implement LMS A This system offers high customizability but costs more.

- Implement LMS B This option is more affordable but has fewer advanced features.

- Develop an in-house solution This would be tailored to the university's needs but would require significant time and resources to develop and maintain.

Conclusion And Reflection

The decision to implement a new LMS involves balancing various needs and constraints. Learners are encouraged to reflect on how these decisions impact different stakeholders and the implications for educational technology decision making.

This case study highlights the importance of data-driven analysis, stakeholder engagement, and strategic planning in successfully implementing technological solutions in educational settings.

The Heart Of A Case Study

A case study is an in-depth examination of a specific event or process in a real-world context. It's a narrative that allows learners to immerse themselves in a situation that mirrors the complexities they might face in their professional lives. Think of it as a story with a purpose—it's about recounting facts and engaging learners in critical thinking and problem solving.

1. Setting The Stage: Contextual Background

Begin by painting a vivid picture of the scenario:

- Why is this case critical?

- How does it tie into the learners' objectives?

In our example, we deal with the university's decision to implement a new Learning Management System (LMS). Describe the university's environment, including any relevant organizational, social, or economic factors. Introduce the stakeholders—the administration, IT department, faculty, students, and LMS vendors. Setting a rich context provides a foundation that helps learners understand the stakes and dynamics at play.

2. Defining The Challenge: Problem Statement

A compelling case study revolves around a well-defined problem. Here, the university's current LMS is outdated, leading to user frustration and inefficiencies in course delivery. Clearly articulating this challenge directs learners' focus and encourages them to think critically. The problem should be specific enough to be meaningful but broad enough to allow for multiple avenues of exploration.

3. Building The Narrative: Data And Evidence

Now, populate your story with detailed information. Use quantitative data like user satisfaction surveys, system performance metrics, and cost analyses. Complement these with qualitative data from interviews, focus groups, and IT department reports. The richness of your data provides a playground for learners to practice data interpretation and evidence-based decision making. It's like giving them pieces of a puzzle and asking them to see the bigger picture.

4. Encouraging Deep Thinking: Analysis

Guide learners through dissecting the data, identifying patterns, and considering different perspectives. In our LMS case study, they might look at how various stakeholders—faculty, students, and IT staff—view the situation. Encourage them to question assumptions and explore alternative explanations. This step is about nurturing analytical skills and fostering a deeper understanding of the scenario.

5. Exploring Solutions: Solution Options

Present multiple potential solutions, each with its pros and cons. LMS A may offer high customizability but at a higher cost, while LMS B is more affordable but has fewer features. Maybe there's even an option to develop an in-house solution tailored to the university's needs. This stage highlights the complexity of decision making in real-world situations and helps learners practice weighing options and considering long-term consequences.

6. Reflecting On The Journey: Conclusion And Reflection

Summarize the key learning points and invite learners to reflect. How does this case study apply to their own experiences or future professional practice? What have they learned about decision making in educational technology? Reflection helps solidify learning and connects theoretical knowledge to practical application.

Also Consider: Weaving In Heutagogical Principles

Heutagogy, or self-determined learning, places the learner at the center of the educational process. By being purposeful about it, we can also design our case study to empower these skills.

Empower Learners: Learner-Centric Design

Give learners ownership of their learning journey. Allow them to explore different paths and solutions based on their interests and prior knowledge. For instance, provide optional resources or additional case scenarios they can choose to explore. This flexibility fosters engagement and personal relevance.

Foster Collaboration: Collaborative Learning

Encourage collaborative activities where learners can discuss and debate different aspects of the case study. Group discussions, forums, and peer reviews enrich the learning experience through social interaction and shared insights. This collaborative approach aligns with social constructivist theories and enhances understanding through dialogue.

Promote Self-Reflection: Reflective Practice

Incorporate reflection prompts throughout the case study. Encourage learners to think about their thought processes and learning outcomes. Journals, reflection papers, and self-assessment quizzes can be practical tools. Reflection deepens learning and promotes self-awareness.

A Practical Blueprint For Writing A Case Study For Online Learning

1. identify the learning objectives.

Start by defining what you want learners to achieve. Align the case study with specific, measurable, and relevant learning outcomes. Clear objectives guide the design process and ensure the case study meets its educational goals.

2. Select A Relevant Scenario

Choose a scenario that resonates with learners' experiences or future professional contexts. Ensure it's complex enough to challenge them but not so obscure that it becomes irrelevant. In our example, the LMS transition is a relatable and timely issue for many educational institutions.

3. Gather Authentic Data

Use real-world data and evidence to construct your narrative. Authenticity enhances credibility and engagement. Sources can include industry reports, interviews with professionals, and actual case records. The more realistic the data, the more engaging and meaningful the case study.

4. Structure The Narrative

Organize the case study into clear, logical sections. Use headings and subheadings to guide readers through the background, problem, data, analysis, solutions, and conclusions. A well-structured narrative aids comprehension and keeps learners focused.

5. Incorporate Interactive Elements

Embed questions, discussion prompts, and activities within the case study. These elements should encourage active participation and critical thinking. Interactive components include multimedia resources, simulations, and scenario-based questions that deepen engagement.

6. Facilitate Assessment And Feedback

Design assessment tools that evaluate learners' understanding and applying the case study. Provide timely and constructive feedback to support continuous improvement. Assessments can range from quizzes and essays to project-based evaluations, ensuring a comprehensive review of learner progress.

Writing case studies as part of the Instructional Design process for online learning is both an art and a science. By meticulously crafting each component, integrating heutagogical principles, and following a practical blueprint, educators can create engaging and meaningful learning experiences. These case studies bridge the gap between theory and practice and empower learners to take control of their educational journeys, fostering a culture of self-directed, lifelong learning.

Creating an academically rigorous and practically relevant case study takes time and effort, but the rewards are immense. Through careful design and thoughtful integration of heutagogical principles, case studies can become powerful tools in online learning, equipping learners with the skills and knowledge they need to thrive professionally.

Making Learning Relevant With Case Studies

The open-ended problems presented in case studies give students work that feels connected to their lives.

Your content has been saved!

To prepare students for jobs that haven’t been created yet, we need to teach them how to be great problem solvers so that they’ll be ready for anything. One way to do this is by teaching content and skills using real-world case studies, a learning model that’s focused on reflection during the problem-solving process. It’s similar to project-based learning, but PBL is more focused on students creating a product.

Case studies have been used for years by businesses, law and medical schools, physicians on rounds, and artists critiquing work. Like other forms of problem-based learning, case studies can be accessible for every age group, both in one subject and in interdisciplinary work.

You can get started with case studies by tackling relatable questions like these with your students:

- How can we limit food waste in the cafeteria?

- How can we get our school to recycle and compost waste? (Or, if you want to be more complex, how can our school reduce its carbon footprint?)

- How can we improve school attendance?

- How can we reduce the number of people who get sick at school during cold and flu season?

Addressing questions like these leads students to identify topics they need to learn more about. In researching the first question, for example, students may see that they need to research food chains and nutrition. Students often ask, reasonably, why they need to learn something, or when they’ll use their knowledge in the future. Learning is most successful for students when the content and skills they’re studying are relevant, and case studies offer one way to create that sense of relevance.

Teaching With Case Studies

Ultimately, a case study is simply an interesting problem with many correct answers. What does case study work look like in classrooms? Teachers generally start by having students read the case or watch a video that summarizes the case. Students then work in small groups or individually to solve the case study. Teachers set milestones defining what students should accomplish to help them manage their time.

During the case study learning process, student assessment of learning should be focused on reflection. Arthur L. Costa and Bena Kallick’s Learning and Leading With Habits of Mind gives several examples of what this reflection can look like in a classroom:

Journaling: At the end of each work period, have students write an entry summarizing what they worked on, what worked well, what didn’t, and why. Sentence starters and clear rubrics or guidelines will help students be successful. At the end of a case study project, as Costa and Kallick write, it’s helpful to have students “select significant learnings, envision how they could apply these learnings to future situations, and commit to an action plan to consciously modify their behaviors.”

Interviews: While working on a case study, students can interview each other about their progress and learning. Teachers can interview students individually or in small groups to assess their learning process and their progress.

Student discussion: Discussions can be unstructured—students can talk about what they worked on that day in a think-pair-share or as a full class—or structured, using Socratic seminars or fishbowl discussions. If your class is tackling a case study in small groups, create a second set of small groups with a representative from each of the case study groups so that the groups can share their learning.

4 Tips for Setting Up a Case Study

1. Identify a problem to investigate: This should be something accessible and relevant to students’ lives. The problem should also be challenging and complex enough to yield multiple solutions with many layers.

2. Give context: Think of this step as a movie preview or book summary. Hook the learners to help them understand just enough about the problem to want to learn more.

3. Have a clear rubric: Giving structure to your definition of quality group work and products will lead to stronger end products. You may be able to have your learners help build these definitions.

4. Provide structures for presenting solutions: The amount of scaffolding you build in depends on your students’ skill level and development. A case study product can be something like several pieces of evidence of students collaborating to solve the case study, and ultimately presenting their solution with a detailed slide deck or an essay—you can scaffold this by providing specified headings for the sections of the essay.

Problem-Based Teaching Resources

There are many high-quality, peer-reviewed resources that are open source and easily accessible online.

- The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science at the University at Buffalo built an online collection of more than 800 cases that cover topics ranging from biochemistry to economics. There are resources for middle and high school students.

- Models of Excellence , a project maintained by EL Education and the Harvard Graduate School of Education, has examples of great problem- and project-based tasks—and corresponding exemplary student work—for grades pre-K to 12.

- The Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning at Purdue University is an open-source journal that publishes examples of problem-based learning in K–12 and post-secondary classrooms.

- The Tech Edvocate has a list of websites and tools related to problem-based learning.

In their book Problems as Possibilities , Linda Torp and Sara Sage write that at the elementary school level, students particularly appreciate how they feel that they are taken seriously when solving case studies. At the middle school level, “researchers stress the importance of relating middle school curriculum to issues of student concern and interest.” And high schoolers, they write, find the case study method “beneficial in preparing them for their future.”

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

What the Case Study Method Really Teaches

- Nitin Nohria

Seven meta-skills that stick even if the cases fade from memory.

It’s been 100 years since Harvard Business School began using the case study method. Beyond teaching specific subject matter, the case study method excels in instilling meta-skills in students. This article explains the importance of seven such skills: preparation, discernment, bias recognition, judgement, collaboration, curiosity, and self-confidence.

During my decade as dean of Harvard Business School, I spent hundreds of hours talking with our alumni. To enliven these conversations, I relied on a favorite question: “What was the most important thing you learned from your time in our MBA program?”

- Nitin Nohria is the George F. Baker Jr. and Distinguished Service University Professor. He served as the 10th dean of Harvard Business School, from 2010 to 2020.

Partner Center

Using Case Studies to Teach

Why Use Cases?

Many students are more inductive than deductive reasoners, which means that they learn better from examples than from logical development starting with basic principles. The use of case studies can therefore be a very effective classroom technique.

Case studies are have long been used in business schools, law schools, medical schools and the social sciences, but they can be used in any discipline when instructors want students to explore how what they have learned applies to real world situations. Cases come in many formats, from a simple “What would you do in this situation?” question to a detailed description of a situation with accompanying data to analyze. Whether to use a simple scenario-type case or a complex detailed one depends on your course objectives.

Most case assignments require students to answer an open-ended question or develop a solution to an open-ended problem with multiple potential solutions. Requirements can range from a one-paragraph answer to a fully developed group action plan, proposal or decision.

Common Case Elements

Most “full-blown” cases have these common elements:

- A decision-maker who is grappling with some question or problem that needs to be solved.

- A description of the problem’s context (a law, an industry, a family).

- Supporting data, which can range from data tables to links to URLs, quoted statements or testimony, supporting documents, images, video, or audio.

Case assignments can be done individually or in teams so that the students can brainstorm solutions and share the work load.

The following discussion of this topic incorporates material presented by Robb Dixon of the School of Management and Rob Schadt of the School of Public Health at CEIT workshops. Professor Dixon also provided some written comments that the discussion incorporates.

Advantages to the use of case studies in class

A major advantage of teaching with case studies is that the students are actively engaged in figuring out the principles by abstracting from the examples. This develops their skills in:

- Problem solving

- Analytical tools, quantitative and/or qualitative, depending on the case

- Decision making in complex situations

- Coping with ambiguities

Guidelines for using case studies in class

In the most straightforward application, the presentation of the case study establishes a framework for analysis. It is helpful if the statement of the case provides enough information for the students to figure out solutions and then to identify how to apply those solutions in other similar situations. Instructors may choose to use several cases so that students can identify both the similarities and differences among the cases.

Depending on the course objectives, the instructor may encourage students to follow a systematic approach to their analysis. For example:

- What is the issue?

- What is the goal of the analysis?

- What is the context of the problem?

- What key facts should be considered?

- What alternatives are available to the decision-maker?

- What would you recommend — and why?

An innovative approach to case analysis might be to have students role-play the part of the people involved in the case. This not only actively engages students, but forces them to really understand the perspectives of the case characters. Videos or even field trips showing the venue in which the case is situated can help students to visualize the situation that they need to analyze.

Accompanying Readings

Case studies can be especially effective if they are paired with a reading assignment that introduces or explains a concept or analytical method that applies to the case. The amount of emphasis placed on the use of the reading during the case discussion depends on the complexity of the concept or method. If it is straightforward, the focus of the discussion can be placed on the use of the analytical results. If the method is more complex, the instructor may need to walk students through its application and the interpretation of the results.

Leading the Case Discussion and Evaluating Performance

Decision cases are more interesting than descriptive ones. In order to start the discussion in class, the instructor can start with an easy, noncontroversial question that all the students should be able to answer readily. However, some of the best case discussions start by forcing the students to take a stand. Some instructors will ask a student to do a formal “open” of the case, outlining his or her entire analysis. Others may choose to guide discussion with questions that move students from problem identification to solutions. A skilled instructor steers questions and discussion to keep the class on track and moving at a reasonable pace.

In order to motivate the students to complete the assignment before class as well as to stimulate attentiveness during the class, the instructor should grade the participation—quantity and especially quality—during the discussion of the case. This might be a simple check, check-plus, check-minus or zero. The instructor should involve as many students as possible. In order to engage all the students, the instructor can divide them into groups, give each group several minutes to discuss how to answer a question related to the case, and then ask a randomly selected person in each group to present the group’s answer and reasoning. Random selection can be accomplished through rolling of dice, shuffled index cards, each with one student’s name, a spinning wheel, etc.

Tips on the Penn State U. website: https://sites.psu.edu/pedagogicalpractices/case-studies/

If you are interested in using this technique in a science course, there is a good website on use of case studies in the sciences at the National Science Teaching Association.

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- AI Essentials for Business

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Creating Brand Value

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurial Marketing

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading Change and Organizational Renewal

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategic Financial Analysis

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

5 Benefits of Learning Through the Case Study Method

- 28 Nov 2023

While several factors make HBS Online unique —including a global Community and real-world outcomes —active learning through the case study method rises to the top.

In a 2023 City Square Associates survey, 74 percent of HBS Online learners who also took a course from another provider said HBS Online’s case method and real-world examples were better by comparison.

Here’s a primer on the case method, five benefits you could gain, and how to experience it for yourself.

Access your free e-book today.

What Is the Harvard Business School Case Study Method?

The case study method , or case method , is a learning technique in which you’re presented with a real-world business challenge and asked how you’d solve it. After working through it yourself and with peers, you’re told how the scenario played out.

HBS pioneered the case method in 1922. Shortly before, in 1921, the first case was written.

“How do you go into an ambiguous situation and get to the bottom of it?” says HBS Professor Jan Rivkin, former senior associate dean and chair of HBS's master of business administration (MBA) program, in a video about the case method . “That skill—the skill of figuring out a course of inquiry to choose a course of action—that skill is as relevant today as it was in 1921.”

Originally developed for the in-person MBA classroom, HBS Online adapted the case method into an engaging, interactive online learning experience in 2014.

In HBS Online courses , you learn about each case from the business professional who experienced it. After reviewing their videos, you’re prompted to take their perspective and explain how you’d handle their situation.

You then get to read peers’ responses, “star” them, and comment to further the discussion. Afterward, you learn how the professional handled it and their key takeaways.

Learn more about HBS Online's approach to the case method in the video below, and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more.

HBS Online’s adaptation of the case method incorporates the famed HBS “cold call,” in which you’re called on at random to make a decision without time to prepare.

“Learning came to life!” said Sheneka Balogun , chief administration officer and chief of staff at LeMoyne-Owen College, of her experience taking the Credential of Readiness (CORe) program . “The videos from the professors, the interactive cold calls where you were randomly selected to participate, and the case studies that enhanced and often captured the essence of objectives and learning goals were all embedded in each module. This made learning fun, engaging, and student-friendly.”

If you’re considering taking a course that leverages the case study method, here are five benefits you could experience.

5 Benefits of Learning Through Case Studies

1. take new perspectives.

The case method prompts you to consider a scenario from another person’s perspective. To work through the situation and come up with a solution, you must consider their circumstances, limitations, risk tolerance, stakeholders, resources, and potential consequences to assess how to respond.

Taking on new perspectives not only can help you navigate your own challenges but also others’. Putting yourself in someone else’s situation to understand their motivations and needs can go a long way when collaborating with stakeholders.

2. Hone Your Decision-Making Skills

Another skill you can build is the ability to make decisions effectively . The case study method forces you to use limited information to decide how to handle a problem—just like in the real world.

Throughout your career, you’ll need to make difficult decisions with incomplete or imperfect information—and sometimes, you won’t feel qualified to do so. Learning through the case method allows you to practice this skill in a low-stakes environment. When facing a real challenge, you’ll be better prepared to think quickly, collaborate with others, and present and defend your solution.

3. Become More Open-Minded

As you collaborate with peers on responses, it becomes clear that not everyone solves problems the same way. Exposing yourself to various approaches and perspectives can help you become a more open-minded professional.

When you’re part of a diverse group of learners from around the world, your experiences, cultures, and backgrounds contribute to a range of opinions on each case.

On the HBS Online course platform, you’re prompted to view and comment on others’ responses, and discussion is encouraged. This practice of considering others’ perspectives can make you more receptive in your career.

“You’d be surprised at how much you can learn from your peers,” said Ratnaditya Jonnalagadda , a software engineer who took CORe.

In addition to interacting with peers in the course platform, Jonnalagadda was part of the HBS Online Community , where he networked with other professionals and continued discussions sparked by course content.

“You get to understand your peers better, and students share examples of businesses implementing a concept from a module you just learned,” Jonnalagadda said. “It’s a very good way to cement the concepts in one's mind.”

4. Enhance Your Curiosity

One byproduct of taking on different perspectives is that it enables you to picture yourself in various roles, industries, and business functions.

“Each case offers an opportunity for students to see what resonates with them, what excites them, what bores them, which role they could imagine inhabiting in their careers,” says former HBS Dean Nitin Nohria in the Harvard Business Review . “Cases stimulate curiosity about the range of opportunities in the world and the many ways that students can make a difference as leaders.”

Through the case method, you can “try on” roles you may not have considered and feel more prepared to change or advance your career .

5. Build Your Self-Confidence

Finally, learning through the case study method can build your confidence. Each time you assume a business leader’s perspective, aim to solve a new challenge, and express and defend your opinions and decisions to peers, you prepare to do the same in your career.

According to a 2022 City Square Associates survey , 84 percent of HBS Online learners report feeling more confident making business decisions after taking a course.

“Self-confidence is difficult to teach or coach, but the case study method seems to instill it in people,” Nohria says in the Harvard Business Review . “There may well be other ways of learning these meta-skills, such as the repeated experience gained through practice or guidance from a gifted coach. However, under the direction of a masterful teacher, the case method can engage students and help them develop powerful meta-skills like no other form of teaching.”

How to Experience the Case Study Method

If the case method seems like a good fit for your learning style, experience it for yourself by taking an HBS Online course. Offerings span eight subject areas, including:

- Business essentials

- Leadership and management

- Entrepreneurship and innovation

- Digital transformation

- Finance and accounting

- Business in society

No matter which course or credential program you choose, you’ll examine case studies from real business professionals, work through their challenges alongside peers, and gain valuable insights to apply to your career.

Are you interested in discovering how HBS Online can help advance your career? Explore our course catalog and download our free guide —complete with interactive workbook sections—to determine if online learning is right for you and which course to take.

About the Author

- International

- Business & Industry

- MyUNB Intranet

- Activate your IT Services

- Give to UNB

- Centre for Enhanced Teaching & Learning

- Teaching & Learning Services

- Teaching Tips

- Instructional Methods

- Creating Effective Scenarios, Case Studies and Role Plays

Creating effective scenarios, case studies and role plays

Printable Version (PDF)

Scenarios, case studies and role plays are examples of active and collaborative teaching techniques that research confirms are effective for the deep learning needed for students to be able to remember and apply concepts once they have finished your course. See Research Findings on University Teaching Methods .

Typically you would use case studies, scenarios and role plays for higher-level learning outcomes that require application, synthesis, and evaluation (see Writing Outcomes or Learning Objectives ; scroll down to the table).

The point is to increase student interest and involvement, and have them practice application by making choices and receive feedback on them, and refine their understanding of concepts and practice in your discipline.

These types of activities provide the following research-based benefits: (Shaw, 3-5)

- They provide concrete examples of abstract concepts, facilitate the development through practice of analytical skills, procedural experience, and decision making skills through application of course concepts in real life situations. This can result in deep learning and the appreciation of differing perspectives.

- They can result in changed perspectives, increased empathy for others, greater insights into challenges faced by others, and increased civic engagement.

- They tend to increase student motivation and interest, as evidenced by increased rates of attendance, completion of assigned readings, and time spent on course work outside of class time.

- Studies show greater/longer retention of learned materials.

- The result is often better teacher/student relations and a more relaxed environment in which the natural exchange of ideas can take place. Students come to see the instructor in a more positive light.

- They often result in better understanding of complexity of situations. They provide a good forum for a large volume of orderly written analysis and discussion.

There are benefits for instructors as well, such as keeping things fresh and interesting in courses they teach repeatedly; providing good feedback on what students are getting and not getting; and helping in standing and promotion in institutions that value teaching and learning.

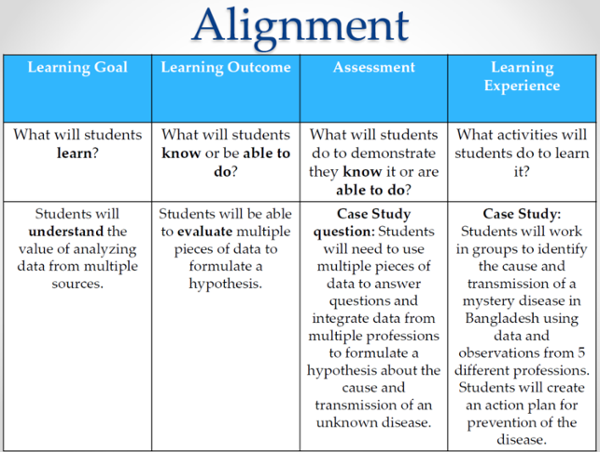

Outcomes and learning activity alignment

The learning activity should have a clear, specific skills and/or knowledge development purpose that is evident to both instructor and students. Students benefit from knowing the purpose of the exercise, learning outcomes it strives to achieve, and evaluation methods. The example shown in the table below is for a case study, but the focus on demonstration of what students will know and can do, and the alignment with appropriate learning activities to achieve those abilities applies to other learning activities.

(Smith, 18)

What’s the difference?

Scenarios are typically short and used to illustrate or apply one main concept. The point is to reinforce concepts and skills as they are taught by providing opportunity to apply them. Scenarios can also be more elaborate, with decision points and further scenario elaboration (multiple storylines), depending on responses. CETL has experience developing scenarios with multiple decision points and branching storylines with UNB faculty using PowerPoint and online educational software.

Case studies

Case studies are typically used to apply several problem-solving concepts and skills to a detailed situation with lots of supporting documentation and data. A case study is usually more complex and detailed than a scenario. It often involves a real-life, well documented situation and the students’ solutions are compared to what was done in the actual case. It generally includes dialogue, creates identification or empathy with the main characters, depending on the discipline. They are best if the situations are recent, relevant to students, have a problem or dilemma to solve, and involve principles that apply broadly.

Role plays can be short like scenarios or longer and more complex, like case studies, but without a lot of the documentation. The idea is to enable students to experience what it may be like to see a problem or issue from many different perspectives as they assume a role they may not typically take, and see others do the same.

Foundational considerations

Typically, scenarios, case studies and role plays should focus on real problems, appropriate to the discipline and course level.

They can be “well-structured” or “ill-structured”:

- Well-structured case studies, problems and scenarios can be simple or complex or anything in-between, but they have an optimal solution and only relevant information is given, and it is usually labelled or otherwise easily identified.

- Ill-structured case studies, problems and scenarios can also be simple or complex, although they tend to be complex. They have relevant and irrelevant information in them, and part of the student’s job is to decide what is relevant, how it is relevant, and to devise an evidence-based solution to the problem that is appropriate to the context and that can be defended by argumentation that draws upon the student’s knowledge of concepts in the discipline.

Well-structured problems would be used to demonstrate understanding and application. Higher learning levels of analysis, synthesis and evaluation are better demonstrated by ill-structured problems.

Scenarios, case studies and role plays can be authentic or realistic :

- Authentic scenarios are actual events that occurred, usually with personal details altered to maintain anonymity. Since the events actually happened, we know that solutions are grounded in reality, not a fictionalized or idealized or simplified situation. This makes them “low transference” in that, since we are dealing with the real world (although in a low-stakes, training situation, often with much more time to resolve the situation than in real life, and just the one thing to work on at a time), not much after-training adjustment to the real world is necessary.

- By contrast, realistic scenarios are often hypothetical situations that may combine aspects of several real-world events, but are artificial in that they are fictionalized and often contain ideal or simplified elements that exist differently in the real world, and some complications are missing. This often means they are easier to solve than real-life issues, and thus are “high transference” in that some after-training adjustment is necessary to deal with the vagaries and complexities of the real world.

Scenarios, case studies and role plays can be high or low fidelity :

High vs. low fidelity: Fidelity has to do with how much a scenario, case study or role play is like its corresponding real world situation. Simplified, well-structured scenarios or problems are most appropriate for beginners. These are low-fidelity, lacking a lot of the detail that must be struggled with in actual practice. As students gain experience and deeper knowledge, the level of complexity and correspondence to real-world situations can be increased until they can solve high fidelity, ill-structured problems and scenarios.

Further details for each

Scenarios can be used in a very wide range of learning and assessment activities. Use in class exercises, seminars, as a content presentation method, exam (e.g., tell students the exam will have four case studies and they have to choose two—this encourages deep studying). Scenarios help instructors reflect on what they are trying to achieve, and modify teaching practice.

For detailed working examples of all types, see pages 7 – 25 of the Psychology Applied Learning Scenarios (PALS) pdf .

The contents of case studies should: (Norton, 6)

- Connect with students’ prior knowledge and help build on it.

- Be presented in a real world context that could plausibly be something they would do in the discipline as a practitioner (e.g., be “authentic”).

- Provide some structure and direction but not too much, since self-directed learning is the goal. They should contain sufficient detail to make the issues clear, but with enough things left not detailed that students have to make assumptions before proceeding (or explore assumptions to determine which are the best to make). “Be ambiguous enough to force them to provide additional factors that influence their approach” (Norton, 6).

- Should have sufficient cues to encourage students to search for explanations but not so many that a lot of time is spent separating relevant and irrelevant cues. Also, too many storyline changes create unnecessary complexity that makes it unnecessarily difficult to deal with.

- Be interesting and engaging and relevant but focus on the mundane, not the bizarre or exceptional (we want to develop skills that will typically be of use in the discipline, not for exceptional circumstances only). Students will relate to case studies more if the depicted situation connects to personal experiences they’ve had.

- Help students fill in knowledge gaps.

Role plays generally have three types of participants: players, observers, and facilitator(s). They also have three phases, as indicated below:

Briefing phase: This stage provides the warm-up, explanations, and asks participants for input on role play scenario. The role play should be somewhat flexible and customizable to the audience. Good role descriptions are sufficiently detailed to let the average person assume the role but not so detailed that there are so many things to remember that it becomes cumbersome. After role assignments, let participants chat a bit about the scenarios and their roles and ask questions. In assigning roles, consider avoiding having visible minorities playing “bad guy” roles. Ensure everyone is comfortable in their role; encourage students to play it up and even overact their role in order to make the point.

Play phase: The facilitator makes seating arrangements (for players and observers), sets up props, arranges any tech support necessary, and does a short introduction. Players play roles, and the facilitator keeps things running smoothly by interjecting directions, descriptions, comments, and encouraging the participation of all roles until players keep things moving without intervention, then withdraws. The facilitator provides a conclusion if one does not arise naturally from the interaction.

Debriefing phase: Role players talk about their experience to the class, facilitated by the instructor or appointee who draws out the main points. All players should describe how they felt and receive feedback from students and the instructor. If the role play involved heated interaction, the debriefing must reconcile any harsh feelings that may otherwise persist due to the exercise.

Five Cs of role playing (AOM, 3)

Control: Role plays often take on a life of their own that moves them in directions other than those intended. Rehearse in your mind a few possible ways this could happen and prepare possible intervention strategies. Perhaps for the first role play you can play a minor role to give you and “in” to exert some control if needed. Once the class has done a few role plays, getting off track becomes less likely. Be sensitive to the possibility that students from different cultures may respond in unforeseen ways to role plays. Perhaps ask students from diverse backgrounds privately in advance for advice on such matters. Perhaps some of these students can assist you as co-moderators or observers.

Controversy: Explain to students that they need to prepare for situations that may provoke them or upset them, and they need to keep their cool and think. Reiterate the learning goals and explain that using this method is worth using because it draws in students more deeply and helps them to feel, not just think, which makes the learning more memorable and more likely to be accessible later. Set up a “safety code word” that students may use at any time to stop the role play and take a break.

Command of details: Students who are more deeply involved may have many more detailed and persistent questions which will require that you have a lot of additional detail about the situation and characters. They may also question the value of role plays as a teaching method, so be prepared with pithy explanations.

Can you help? Students may be concerned about how their acting will affect their grade, and want assistance in determining how to play their assigned character and need time to get into their role. Tell them they will not be marked on their acting. Say there is no single correct way to play a character. Prepare for slow starts, gaps in the action, and awkward moments. If someone really doesn’t want to take a role, let them participate by other means—as a recorder, moderator, technical support, observer, props…

Considered reflection: Reflection and discussion are the main ways of learning from role plays. Players should reflect on what they felt, perceived, and learned from the session. Review the key events of the role play and consider what people would do differently and why. Include reflections of observers. Facilitate the discussion, but don’t impose your opinions, and play a neutral, background role. Be prepared to start with some of your own feedback if discussion is slow to start.

An engineering role play adaptation

Boundary objects (e.g., storyboards) have been used in engineering and computer science design projects to facilitate collaboration between specialists from different disciplines (Diaz, 6-80). In one instance, role play was used in a collaborative design workshop as a way of making computer scientist or engineering students play project roles they are not accustomed to thinking about, such as project manager, designer, user design specialist, etc. (Diaz 6-81).

References:

Academy of Management. (Undated). Developing a Role playing Case Study as a Teaching Tool.

Diaz, L., Reunanen, M., & Salimi, A. (2009, August). Role Playing and Collaborative Scenario Design Development. Paper presented at the International Conference of Engineering Design, Stanford University, California.

Norton, L. (2004). Psychology Applied Learning Scenarios (PALS): A practical introduction to problem-based learning using vignettes for psychology lecturers . Liverpool Hope University College.

Shaw, C. M. (2010). Designing and Using Simulations and Role-Play Exercises in The International Studies Encyclopedia, eISBN: 9781444336597

Smith, A. R. & Evanstone, A. (Undated). Writing Effective Case Studies in the Sciences: Backward Design and Global Learning Outcomes. Institute for Biological Education, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

- Campus Maps

- Campus Security

- Careers at UNB

- Services at UNB

- Conference Services

- Online & Continuing Ed

Contact UNB

- © University of New Brunswick

- Accessibility

- Web feedback

- Columbia University in the City of New York

- Office of Teaching, Learning, and Innovation

- University Policies

- Columbia Online

- Academic Calendar

- Resources and Technology

- Resources and Guides

Case Method Teaching and Learning

What is the case method? How can the case method be used to engage learners? What are some strategies for getting started? This guide helps instructors answer these questions by providing an overview of the case method while highlighting learner-centered and digitally-enhanced approaches to teaching with the case method. The guide also offers tips to instructors as they get started with the case method and additional references and resources.

On this page:

What is case method teaching.

- Case Method at Columbia

Why use the Case Method?

Case method teaching approaches, how do i get started.

- Additional Resources

The CTL is here to help!

For support with implementing a case method approach in your course, email [email protected] to schedule your 1-1 consultation .

Cite this resource: Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2019). Case Method Teaching and Learning. Columbia University. Retrieved from [today’s date] from https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/resources/case-method/

Case method 1 teaching is an active form of instruction that focuses on a case and involves students learning by doing 2 3 . Cases are real or invented stories 4 that include “an educational message” or recount events, problems, dilemmas, theoretical or conceptual issue that requires analysis and/or decision-making.

Case-based teaching simulates real world situations and asks students to actively grapple with complex problems 5 6 This method of instruction is used across disciplines to promote learning, and is common in law, business, medicine, among other fields. See Table 1 below for a few types of cases and the learning they promote.

Table 1: Types of cases and the learning they promote.

For a more complete list, see Case Types & Teaching Methods: A Classification Scheme from the National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science.

Back to Top

Case Method Teaching and Learning at Columbia

The case method is actively used in classrooms across Columbia, at the Morningside campus in the School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA), the School of Business, Arts and Sciences, among others, and at Columbia University Irving Medical campus.

Faculty Spotlight:

Professor Mary Ann Price on Using Case Study Method to Place Pre-Med Students in Real-Life Scenarios

Read more

Professor De Pinho on Using the Case Method in the Mailman Core

Case method teaching has been found to improve student learning, to increase students’ perception of learning gains, and to meet learning objectives 8 9 . Faculty have noted the instructional benefits of cases including greater student engagement in their learning 10 , deeper student understanding of concepts, stronger critical thinking skills, and an ability to make connections across content areas and view an issue from multiple perspectives 11 .

Through case-based learning, students are the ones asking questions about the case, doing the problem-solving, interacting with and learning from their peers, “unpacking” the case, analyzing the case, and summarizing the case. They learn how to work with limited information and ambiguity, think in professional or disciplinary ways, and ask themselves “what would I do if I were in this specific situation?”

The case method bridges theory to practice, and promotes the development of skills including: communication, active listening, critical thinking, decision-making, and metacognitive skills 12 , as students apply course content knowledge, reflect on what they know and their approach to analyzing, and make sense of a case.

Though the case method has historical roots as an instructor-centered approach that uses the Socratic dialogue and cold-calling, it is possible to take a more learner-centered approach in which students take on roles and tasks traditionally left to the instructor.

Cases are often used as “vehicles for classroom discussion” 13 . Students should be encouraged to take ownership of their learning from a case. Discussion-based approaches engage students in thinking and communicating about a case. Instructors can set up a case activity in which students are the ones doing the work of “asking questions, summarizing content, generating hypotheses, proposing theories, or offering critical analyses” 14 .

The role of the instructor is to share a case or ask students to share or create a case to use in class, set expectations, provide instructions, and assign students roles in the discussion. Student roles in a case discussion can include:

- discussion “starters” get the conversation started with a question or posing the questions that their peers came up with;

- facilitators listen actively, validate the contributions of peers, ask follow-up questions, draw connections, refocus the conversation as needed;

- recorders take-notes of the main points of the discussion, record on the board, upload to CourseWorks, or type and project on the screen; and

- discussion “wrappers” lead a summary of the main points of the discussion.

Prior to the case discussion, instructors can model case analysis and the types of questions students should ask, co-create discussion guidelines with students, and ask for students to submit discussion questions. During the discussion, the instructor can keep time, intervene as necessary (however the students should be doing the talking), and pause the discussion for a debrief and to ask students to reflect on what and how they learned from the case activity.

Note: case discussions can be enhanced using technology. Live discussions can occur via video-conferencing (e.g., using Zoom ) or asynchronous discussions can occur using the Discussions tool in CourseWorks (Canvas) .

Table 2 includes a few interactive case method approaches. Regardless of the approach selected, it is important to create a learning environment in which students feel comfortable participating in a case activity and learning from one another. See below for tips on supporting student in how to learn from a case in the “getting started” section and how to create a supportive learning environment in the Guide for Inclusive Teaching at Columbia .

Table 2. Strategies for Engaging Students in Case-Based Learning

Approaches to case teaching should be informed by course learning objectives, and can be adapted for small, large, hybrid, and online classes. Instructional technology can be used in various ways to deliver, facilitate, and assess the case method. For instance, an online module can be created in CourseWorks (Canvas) to structure the delivery of the case, allow students to work at their own pace, engage all learners, even those reluctant to speak up in class, and assess understanding of a case and student learning. Modules can include text, embedded media (e.g., using Panopto or Mediathread ) curated by the instructor, online discussion, and assessments. Students can be asked to read a case and/or watch a short video, respond to quiz questions and receive immediate feedback, post questions to a discussion, and share resources.

For more information about options for incorporating educational technology to your course, please contact your Learning Designer .

To ensure that students are learning from the case approach, ask them to pause and reflect on what and how they learned from the case. Time to reflect builds your students’ metacognition, and when these reflections are collected they provides you with insights about the effectiveness of your approach in promoting student learning.

Well designed case-based learning experiences: 1) motivate student involvement, 2) have students doing the work, 3) help students develop knowledge and skills, and 4) have students learning from each other.

Designing a case-based learning experience should center around the learning objectives for a course. The following points focus on intentional design.

Identify learning objectives, determine scope, and anticipate challenges.

- Why use the case method in your course? How will it promote student learning differently than other approaches?

- What are the learning objectives that need to be met by the case method? What knowledge should students apply and skills should they practice?

- What is the scope of the case? (a brief activity in a single class session to a semester-long case-based course; if new to case method, start small with a single case).

- What challenges do you anticipate (e.g., student preparation and prior experiences with case learning, discomfort with discussion, peer-to-peer learning, managing discussion) and how will you plan for these in your design?

- If you are asking students to use transferable skills for the case method (e.g., teamwork, digital literacy) make them explicit.

Determine how you will know if the learning objectives were met and develop a plan for evaluating the effectiveness of the case method to inform future case teaching.

- What assessments and criteria will you use to evaluate student work or participation in case discussion?

- How will you evaluate the effectiveness of the case method? What feedback will you collect from students?

- How might you leverage technology for assessment purposes? For example, could you quiz students about the case online before class, accept assignment submissions online, use audience response systems (e.g., PollEverywhere) for formative assessment during class?

Select an existing case, create your own, or encourage students to bring course-relevant cases, and prepare for its delivery

- Where will the case method fit into the course learning sequence?

- Is the case at the appropriate level of complexity? Is it inclusive, culturally relevant, and relatable to students?

- What materials and preparation will be needed to present the case to students? (e.g., readings, audiovisual materials, set up a module in CourseWorks).

Plan for the case discussion and an active role for students

- What will your role be in facilitating case-based learning? How will you model case analysis for your students? (e.g., present a short case and demo your approach and the process of case learning) (Davis, 2009).

- What discussion guidelines will you use that include your students’ input?

- How will you encourage students to ask and answer questions, summarize their work, take notes, and debrief the case?

- If students will be working in groups, how will groups form? What size will the groups be? What instructions will they be given? How will you ensure that everyone participates? What will they need to submit? Can technology be leveraged for any of these areas?

- Have you considered students of varied cognitive and physical abilities and how they might participate in the activities/discussions, including those that involve technology?

Student preparation and expectations

- How will you communicate about the case method approach to your students? When will you articulate the purpose of case-based learning and expectations of student engagement? What information about case-based learning and expectations will be included in the syllabus?

- What preparation and/or assignment(s) will students complete in order to learn from the case? (e.g., read the case prior to class, watch a case video prior to class, post to a CourseWorks discussion, submit a brief memo, complete a short writing assignment to check students’ understanding of a case, take on a specific role, prepare to present a critique during in-class discussion).

Andersen, E. and Schiano, B. (2014). Teaching with Cases: A Practical Guide . Harvard Business Press.

Bonney, K. M. (2015). Case Study Teaching Method Improves Student Performance and Perceptions of Learning Gains†. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education , 16 (1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1128/jmbe.v16i1.846

Davis, B.G. (2009). Chapter 24: Case Studies. In Tools for Teaching. Second Edition. Jossey-Bass.

Garvin, D.A. (2003). Making the Case: Professional Education for the world of practice. Harvard Magazine. September-October 2003, Volume 106, Number 1, 56-107.

Golich, V.L. (2000). The ABCs of Case Teaching. International Studies Perspectives. 1, 11-29.

Golich, V.L.; Boyer, M; Franko, P.; and Lamy, S. (2000). The ABCs of Case Teaching. Pew Case Studies in International Affairs. Institute for the Study of Diplomacy.

Heath, J. (2015). Teaching & Writing Cases: A Practical Guide. The Case Center, UK.

Herreid, C.F. (2011). Case Study Teaching. New Directions for Teaching and Learning. No. 128, Winder 2011, 31 – 40.

Herreid, C.F. (2007). Start with a Story: The Case Study Method of Teaching College Science . National Science Teachers Association. Available as an ebook through Columbia Libraries.

Herreid, C.F. (2006). “Clicker” Cases: Introducing Case Study Teaching Into Large Classrooms. Journal of College Science Teaching. Oct 2006, 36(2). https://search.proquest.com/docview/200323718?pq-origsite=gscholar

Krain, M. (2016). Putting the Learning in Case Learning? The Effects of Case-Based Approaches on Student Knowledge, Attitudes, and Engagement. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching. 27(2), 131-153.

Lundberg, K.O. (Ed.). (2011). Our Digital Future: Boardrooms and Newsrooms. Knight Case Studies Initiative.

Popil, I. (2011). Promotion of critical thinking by using case studies as teaching method. Nurse Education Today, 31(2), 204–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2010.06.002

Schiano, B. and Andersen, E. (2017). Teaching with Cases Online . Harvard Business Publishing.

Thistlethwaite, JE; Davies, D.; Ekeocha, S.; Kidd, J.M.; MacDougall, C.; Matthews, P.; Purkis, J.; Clay D. (2012). The effectiveness of case-based learning in health professional education: A BEME systematic review . Medical Teacher. 2012; 34(6): e421-44.

Yadav, A.; Lundeberg, M.; DeSchryver, M.; Dirkin, K.; Schiller, N.A.; Maier, K. and Herreid, C.F. (2007). Teaching Science with Case Studies: A National Survey of Faculty Perceptions of the Benefits and Challenges of Using Cases. Journal of College Science Teaching; Sept/Oct 2007; 37(1).

Weimer, M. (2013). Learner-Centered Teaching: Five Key Changes to Practice. Second Edition. Jossey-Bass.

Additional resources

Teaching with Cases , Harvard Kennedy School of Government.

Features “what is a teaching case?” video that defines a teaching case, and provides documents to help students prepare for case learning, Common case teaching challenges and solutions, tips for teaching with cases.

Promoting excellence and innovation in case method teaching: Teaching by the Case Method , Christensen Center for Teaching & Learning. Harvard Business School.

National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science . University of Buffalo.

A collection of peer-reviewed STEM cases to teach scientific concepts and content, promote process skills and critical thinking. The Center welcomes case submissions. Case classification scheme of case types and teaching methods:

- Different types of cases: analysis case, dilemma/decision case, directed case, interrupted case, clicker case, a flipped case, a laboratory case.

- Different types of teaching methods: problem-based learning, discussion, debate, intimate debate, public hearing, trial, jigsaw, role-play.

Columbia Resources

Resources available to support your use of case method: The University hosts a number of case collections including: the Case Consortium (a collection of free cases in the fields of journalism, public policy, public health, and other disciplines that include teaching and learning resources; SIPA’s Picker Case Collection (audiovisual case studies on public sector innovation, filmed around the world and involving SIPA student teams in producing the cases); and Columbia Business School CaseWorks , which develops teaching cases and materials for use in Columbia Business School classrooms.

Center for Teaching and Learning

The Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) offers a variety of programs and services for instructors at Columbia. The CTL can provide customized support as you plan to use the case method approach through implementation. Schedule a one-on-one consultation.

Office of the Provost

The Hybrid Learning Course Redesign grant program from the Office of the Provost provides support for faculty who are developing innovative and technology-enhanced pedagogy and learning strategies in the classroom. In addition to funding, faculty awardees receive support from CTL staff as they redesign, deliver, and evaluate their hybrid courses.

The Start Small! Mini-Grant provides support to faculty who are interested in experimenting with one new pedagogical strategy or tool. Faculty awardees receive funds and CTL support for a one-semester period.

Explore our teaching resources.

- Blended Learning

- Contemplative Pedagogy

- Inclusive Teaching Guide

- FAQ for Teaching Assistants

- Metacognition

CTL resources and technology for you.

- Overview of all CTL Resources and Technology

- The origins of this method can be traced to Harvard University where in 1870 the Law School began using cases to teach students how to think like lawyers using real court decisions. This was followed by the Business School in 1920 (Garvin, 2003). These professional schools recognized that lecture mode of instruction was insufficient to teach critical professional skills, and that active learning would better prepare learners for their professional lives. ↩

- Golich, V.L. (2000). The ABCs of Case Teaching. International Studies Perspectives. 1, 11-29. ↩

- Herreid, C.F. (2007). Start with a Story: The Case Study Method of Teaching College Science . National Science Teachers Association. Available as an ebook through Columbia Libraries. ↩

- Davis, B.G. (2009). Chapter 24: Case Studies. In Tools for Teaching. Second Edition. Jossey-Bass. ↩

- Andersen, E. and Schiano, B. (2014). Teaching with Cases: A Practical Guide . Harvard Business Press. ↩

- Lundberg, K.O. (Ed.). (2011). Our Digital Future: Boardrooms and Newsrooms. Knight Case Studies Initiative. ↩

- Heath, J. (2015). Teaching & Writing Cases: A Practical Guide. The Case Center, UK. ↩

- Bonney, K. M. (2015). Case Study Teaching Method Improves Student Performance and Perceptions of Learning Gains†. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education , 16 (1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1128/jmbe.v16i1.846 ↩

- Krain, M. (2016). Putting the Learning in Case Learning? The Effects of Case-Based Approaches on Student Knowledge, Attitudes, and Engagement. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching. 27(2), 131-153. ↩

- Thistlethwaite, JE; Davies, D.; Ekeocha, S.; Kidd, J.M.; MacDougall, C.; Matthews, P.; Purkis, J.; Clay D. (2012). The effectiveness of case-based learning in health professional education: A BEME systematic review . Medical Teacher. 2012; 34(6): e421-44. ↩

- Yadav, A.; Lundeberg, M.; DeSchryver, M.; Dirkin, K.; Schiller, N.A.; Maier, K. and Herreid, C.F. (2007). Teaching Science with Case Studies: A National Survey of Faculty Perceptions of the Benefits and Challenges of Using Cases. Journal of College Science Teaching; Sept/Oct 2007; 37(1). ↩

- Popil, I. (2011). Promotion of critical thinking by using case studies as teaching method. Nurse Education Today, 31(2), 204–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2010.06.002 ↩

- Weimer, M. (2013). Learner-Centered Teaching: Five Key Changes to Practice. Second Edition. Jossey-Bass. ↩

- Herreid, C.F. (2006). “Clicker” Cases: Introducing Case Study Teaching Into Large Classrooms. Journal of College Science Teaching. Oct 2006, 36(2). https://search.proquest.com/docview/200323718?pq-origsite=gscholar ↩

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

A Practical Blueprint For Writing A Case Study For Online Learning 1. Identify The Learning Objectives. Start by defining what you want learners to achieve. Align the case study with specific, measurable, and relevant learning outcomes. Clear objectives guide the design process and ensure the case study meets its educational goals. 2.

To prepare students for jobs that haven’t been created yet, we need to teach them how to be great problem solvers so that they’ll be ready for anything. One way to do this is by teaching content and skills using real-world case studies, a learning model that’s focused on reflection during the problem-solving process.

Beyond teaching specific subject matter, the case study method excels in instilling meta-skills in students. This article explains the importance of seven such skills: preparation, discernment,...

This guide explores what case studies are, the value of using case studies as teaching tools, and how to implement them in your teaching. What are case studies? Case studies are stories that are used as a teaching tool to show the application of a theory or concept to real situations.

Most case assignments require students to answer an open-ended question or develop a solution to an open-ended problem with multiple potential solutions. Requirements can range from a one-paragraph answer to a fully developed group action plan, proposal or decision.

If you’re considering taking a course that leverages the case study method, here are five benefits you could experience. 5 Benefits of Learning Through Case Studies 1. Take New Perspectives. The case method prompts you to consider a scenario from another person’s perspective.

Scenarios, case studies and role plays are examples of active and collaborative teaching techniques that research confirms are effective for the deep learning needed for students to be able to remember and apply concepts once they have finished your course.

The case study teaching method is a highly adaptable style of teaching that involves problem-based learning and promotes the development of analytical skills (Herreid, Schiller, Herreid, & Wright, 2011).

Students are given the case in parts that they work on and make decisions about before moving on to the next part. Focuses on answering questions and analyzing the situation presented. This can include “retrospective” cases that tell a story and its outcomes and have students analyze what happened and why alternative solutions were not taken.

Cases challenge learners to make practical suggestions to issues that they may encounter and allows for active learn-ing. Indeed, the case teaching method has progressed from the practical to the more evidence-based, theoretical, and empiri-cally informed approach to learning.