Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

12.2 Developing a Final Draft of a Research Paper

Learning objectives.

- Revise your paper to improve organization and cohesion.

- Determine an appropriate style and tone for your paper.

- Revise to ensure that your tone is consistent.

- Edit your paper to ensure that language, citations, and formatting are correct.

Given all the time and effort you have put into your research project, you will want to make sure that your final draft represents your best work. This requires taking the time to revise and edit your paper carefully.

You may feel like you need a break from your paper before you revise and edit it. That is understandable—but leave yourself with enough time to complete this important stage of the writing process. In this section, you will learn the following specific strategies that are useful for revising and editing a research paper:

- How to evaluate and improve the overall organization and cohesion

- How to maintain an appropriate style and tone

- How to use checklists to identify and correct any errors in language, citations, and formatting

Revising Your Paper: Organization and Cohesion

When writing a research paper, it is easy to become overly focused on editorial details, such as the proper format for bibliographical entries. These details do matter. However, before you begin to address them, it is important to spend time reviewing and revising the content of the paper.

A good research paper is both organized and cohesive. Organization means that your argument flows logically from one point to the next. Cohesion means that the elements of your paper work together smoothly and naturally. In a cohesive research paper, information from research is seamlessly integrated with the writer’s ideas.

Revise to Improve Organization

When you revise to improve organization, you look at the flow of ideas throughout the essay as a whole and within individual paragraphs. You check to see that your essay moves logically from the introduction to the body paragraphs to the conclusion, and that each section reinforces your thesis. Use Checklist 12.1 to help you.

Checklist 12.1

Revision: Organization

At the essay level

- Does my introduction proceed clearly from the opening to the thesis?

- Does each body paragraph have a clear main idea that relates to the thesis?

- Do the main ideas in the body paragraphs flow in a logical order? Is each paragraph connected to the one before it?

- Do I need to add or revise topic sentences or transitions to make the overall flow of ideas clearer?

- Does my conclusion summarize my main ideas and revisit my thesis?

At the paragraph level

- Does the topic sentence clearly state the main idea?

- Do the details in the paragraph relate to the main idea?

- Do I need to recast any sentences or add transitions to improve the flow of sentences?

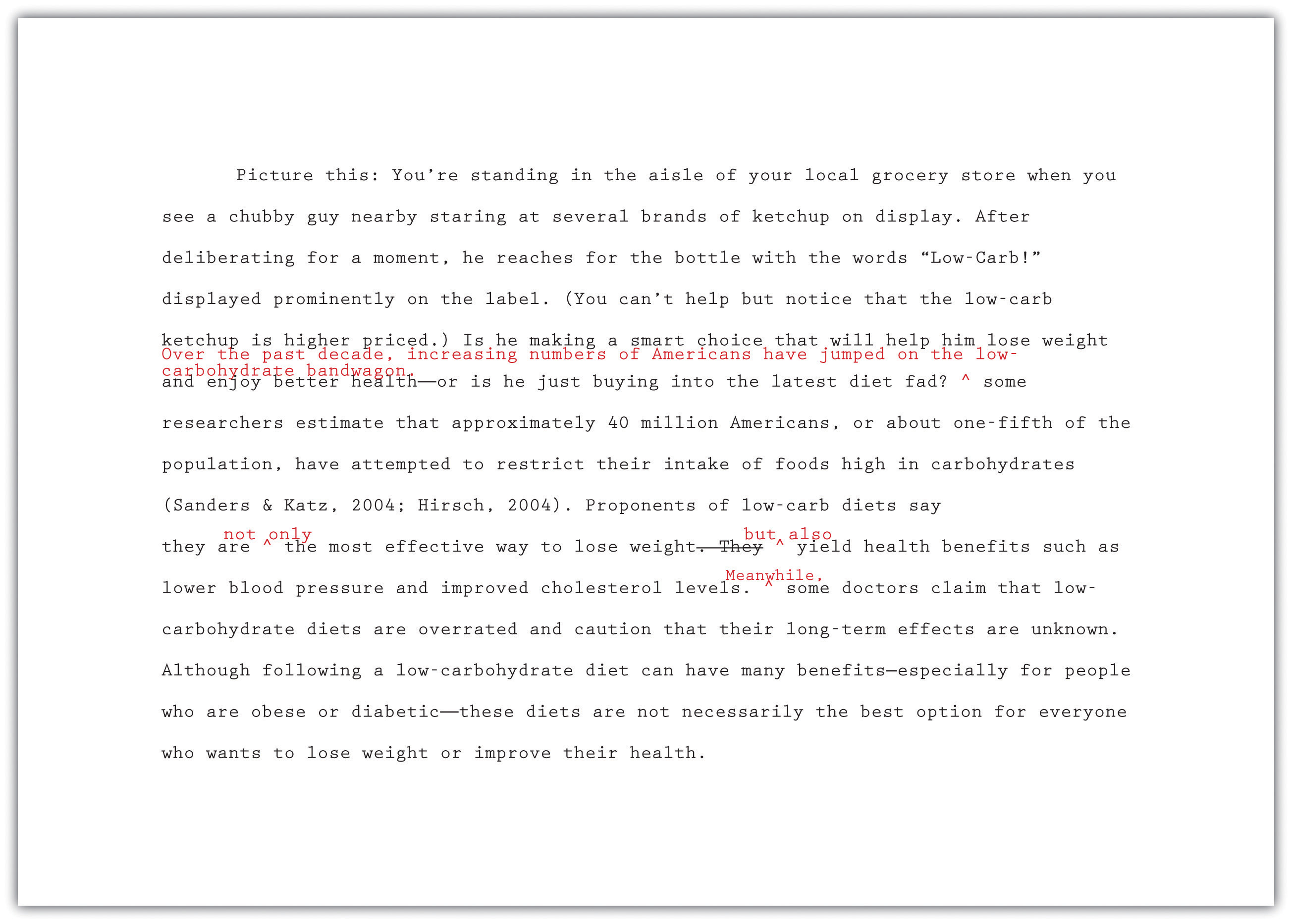

Jorge reread his draft paragraph by paragraph. As he read, he highlighted the main idea of each paragraph so he could see whether his ideas proceeded in a logical order. For the most part, the flow of ideas was clear. However, he did notice that one paragraph did not have a clear main idea. It interrupted the flow of the writing. During revision, Jorge added a topic sentence that clearly connected the paragraph to the one that had preceded it. He also added transitions to improve the flow of ideas from sentence to sentence.

Read the following paragraphs twice, the first time without Jorge’s changes, and the second time with them.

Follow these steps to begin revising your paper’s overall organization.

- Print out a hard copy of your paper.

- Read your paper paragraph by paragraph. Highlight your thesis and the topic sentence of each paragraph.

- Using the thesis and topic sentences as starting points, outline the ideas you presented—just as you would do if you were outlining a chapter in a textbook. Do not look at the outline you created during prewriting. You may write in the margins of your draft or create a formal outline on a separate sheet of paper.

- Next, reread your paper more slowly, looking for how ideas flow from sentence to sentence. Identify places where adding a transition or recasting a sentence would make the ideas flow more logically.

- Review the topics on your outline. Is there a logical flow of ideas? Identify any places where you may need to reorganize ideas.

- Begin to revise your paper to improve organization. Start with any major issues, such as needing to move an entire paragraph. Then proceed to minor revisions, such as adding a transitional phrase or tweaking a topic sentence so it connects ideas more clearly.

Collaboration

Please share your paper with a classmate. Repeat the six steps and take notes on a separate piece of paper. Share and compare notes.

Writers choose transitions carefully to show the relationships between ideas—for instance, to make a comparison or elaborate on a point with examples. Make sure your transitions suit your purpose and avoid overusing the same ones. For an extensive list of transitions, see Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” , Section 8.4 “Revising and Editing” .

Revise to Improve Cohesion

When you revise to improve cohesion, you analyze how the parts of your paper work together. You look for anything that seems awkward or out of place. Revision may involve deleting unnecessary material or rewriting parts of the paper so that the out-of-place material fits in smoothly.

In a research paper, problems with cohesion usually occur when a writer has trouble integrating source material. If facts or quotations have been awkwardly dropped into a paragraph, they distract or confuse the reader instead of working to support the writer’s point. Overusing paraphrased and quoted material has the same effect. Use Checklist 12.2 to review your essay for cohesion.

Checklist 12.2

Revision: Cohesion

- Does the opening of the paper clearly connect to the broader topic and thesis? Make sure entertaining quotes or anecdotes serve a purpose.

- Have I included support from research for each main point in the body of my paper?

- Have I included introductory material before any quotations? Quotations should never stand alone in a paragraph.

- Does paraphrased and quoted material clearly serve to develop my own points?

- Do I need to add to or revise parts of the paper to help the reader understand how certain information from a source is relevant?

- Are there any places where I have overused material from sources?

- Does my conclusion make sense based on the rest of the paper? Make sure any new questions or suggestions in the conclusion are clearly linked to earlier material.

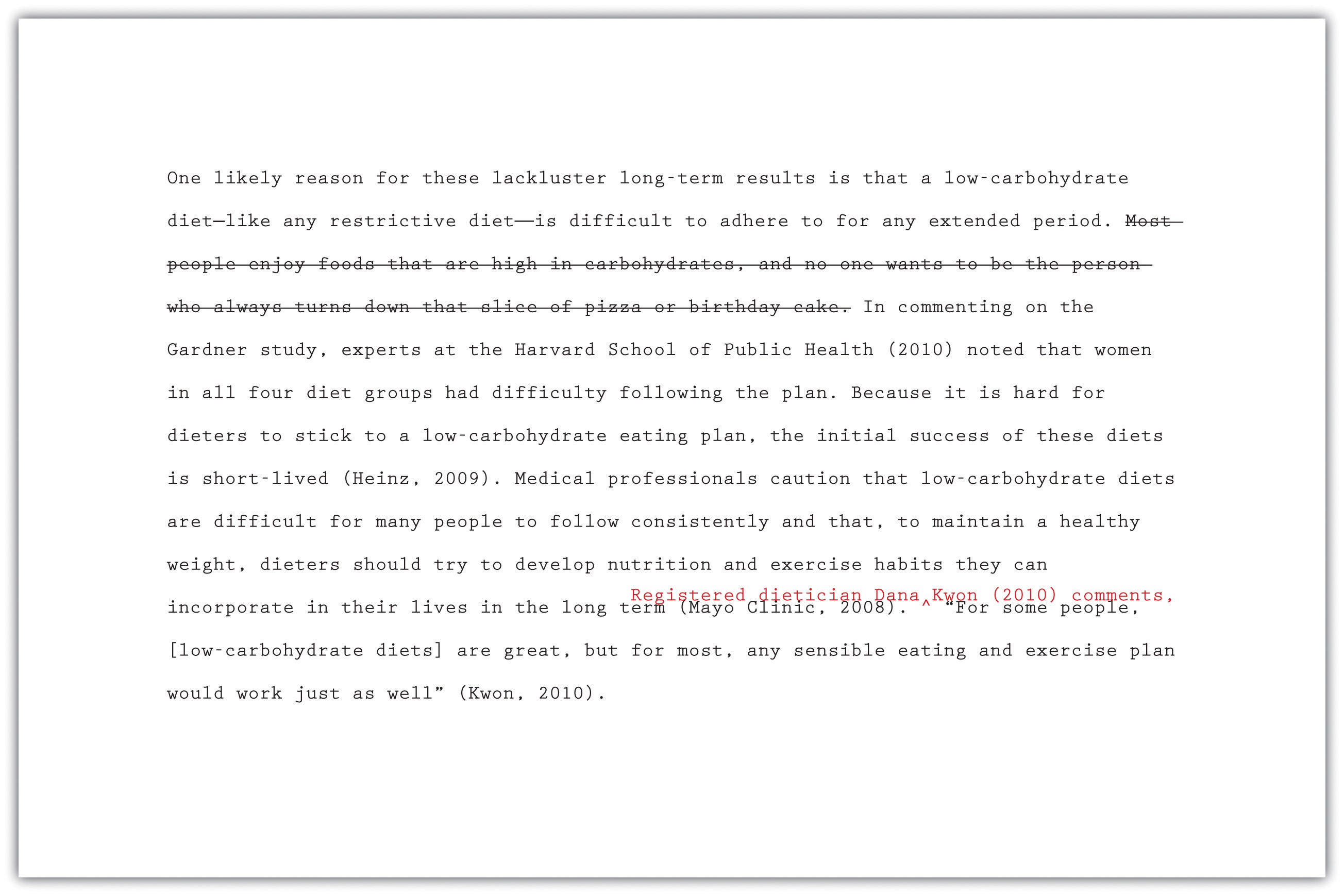

As Jorge reread his draft, he looked to see how the different pieces fit together to prove his thesis. He realized that some of his supporting information needed to be integrated more carefully and decided to omit some details entirely. Read the following paragraph, first without Jorge’s revisions and then with them.

Jorge decided that his comment about pizza and birthday cake came across as subjective and was not necessary to make his point, so he deleted it. He also realized that the quotation at the end of the paragraph was awkward and ineffective. How would his readers know who Kwon was or why her opinion should be taken seriously? Adding an introductory phrase helped Jorge integrate this quotation smoothly and establish the credibility of his source.

Follow these steps to begin revising your paper to improve cohesion.

- Print out a hard copy of your paper, or work with your printout from Note 12.33 “Exercise 1” .

- Read the body paragraphs of your paper first. Each time you come to a place that cites information from sources, ask yourself what purpose this information serves. Check that it helps support a point and that it is clearly related to the other sentences in the paragraph.

- Identify unnecessary information from sources that you can delete.

- Identify places where you need to revise your writing so that readers understand the significance of the details cited from sources.

- Skim the body paragraphs once more, looking for any paragraphs that seem packed with citations. Review these paragraphs carefully for cohesion.

- Review your introduction and conclusion. Make sure the information presented works with ideas in the body of the paper.

- Revise the places you identified in your paper to improve cohesion.

Please exchange papers with a classmate. Complete step four. On a separate piece of paper, note any areas that would benefit from clarification. Return and compare notes.

Writing at Work

Understanding cohesion can also benefit you in the workplace, especially when you have to write and deliver a presentation. Speakers sometimes rely on cute graphics or funny quotations to hold their audience’s attention. If you choose to use these elements, make sure they work well with the substantive content of your presentation. For example, if you are asked to give a financial presentation, and the financial report shows that the company lost money, funny illustrations would not be relevant or appropriate for the presentation.

Using a Consistent Style and Tone

Once you are certain that the content of your paper fulfills your purpose, you can begin revising to improve style and tone . Together, your style and tone create the voice of your paper, or how you come across to readers. Style refers to the way you use language as a writer—the sentence structures you use and the word choices you make. Tone is the attitude toward your subject and audience that you convey through your word choice.

Determining an Appropriate Style and Tone

Although accepted writing styles will vary within different disciplines, the underlying goal is the same—to come across to your readers as a knowledgeable, authoritative guide. Writing about research is like being a tour guide who walks readers through a topic. A stuffy, overly formal tour guide can make readers feel put off or intimidated. Too much informality or humor can make readers wonder whether the tour guide really knows what he or she is talking about. Extreme or emotionally charged language comes across as unbalanced.

To help prevent being overly formal or informal, determine an appropriate style and tone at the beginning of the research process. Consider your topic and audience because these can help dictate style and tone. For example, a paper on new breakthroughs in cancer research should be more formal than a paper on ways to get a good night’s sleep.

A strong research paper comes across as straightforward, appropriately academic, and serious. It is generally best to avoid writing in the first person, as this can make your paper seem overly subjective and opinion based. Use Checklist 12.3 on style to review your paper for other issues that affect style and tone. You can check for consistency at the end of the writing process. Checking for consistency is discussed later in this section.

Checklist 12.3

- My paper avoids excessive wordiness.

- My sentences are varied in length and structure.

- I have avoided using first-person pronouns such as I and we .

- I have used the active voice whenever possible.

- I have defined specialized terms that might be unfamiliar to readers.

- I have used clear, straightforward language whenever possible and avoided unnecessary jargon.

- My paper states my point of view using a balanced tone—neither too indecisive nor too forceful.

Word Choice

Note that word choice is an especially important aspect of style. In addition to checking the points noted on Checklist 12.3, review your paper to make sure your language is precise, conveys no unintended connotations, and is free of biases. Here are some of the points to check for:

- Vague or imprecise terms

- Repetition of the same phrases (“Smith states…, Jones states…”) to introduce quoted and paraphrased material (For a full list of strong verbs to use with in-text citations, see Chapter 13 “APA and MLA Documentation and Formatting” .)

- Exclusive use of masculine pronouns or awkward use of he or she

- Use of language with negative connotations, such as haughty or ridiculous

- Use of outdated or offensive terms to refer to specific ethnic, racial, or religious groups

Using plural nouns and pronouns or recasting a sentence can help you keep your language gender neutral while avoiding awkwardness. Consider the following examples.

- Gender-biased: When a writer cites a source in the body of his paper, he must list it on his references page.

- Awkward: When a writer cites a source in the body of his or her paper, he or she must list it on his or her references page.

- Improved: Writers must list any sources cited in the body of a paper on the references page.

Keeping Your Style Consistent

As you revise your paper, make sure your style is consistent throughout. Look for instances where a word, phrase, or sentence just does not seem to fit with the rest of the writing. It is best to reread for style after you have completed the other revisions so that you are not distracted by any larger content issues. Revising strategies you can use include the following:

- Read your paper aloud. Sometimes your ears catch inconsistencies that your eyes miss.

- Share your paper with another reader whom you trust to give you honest feedback. It is often difficult to evaluate one’s own style objectively—especially in the final phase of a challenging writing project. Another reader may be more likely to notice instances of wordiness, confusing language, or other issues that affect style and tone.

- Line-edit your paper slowly, sentence by sentence. You may even wish to use a sheet of paper to cover everything on the page except the paragraph you are editing—that forces you to read slowly and carefully. Mark any areas where you notice problems in style or tone, and then take time to rework those sections.

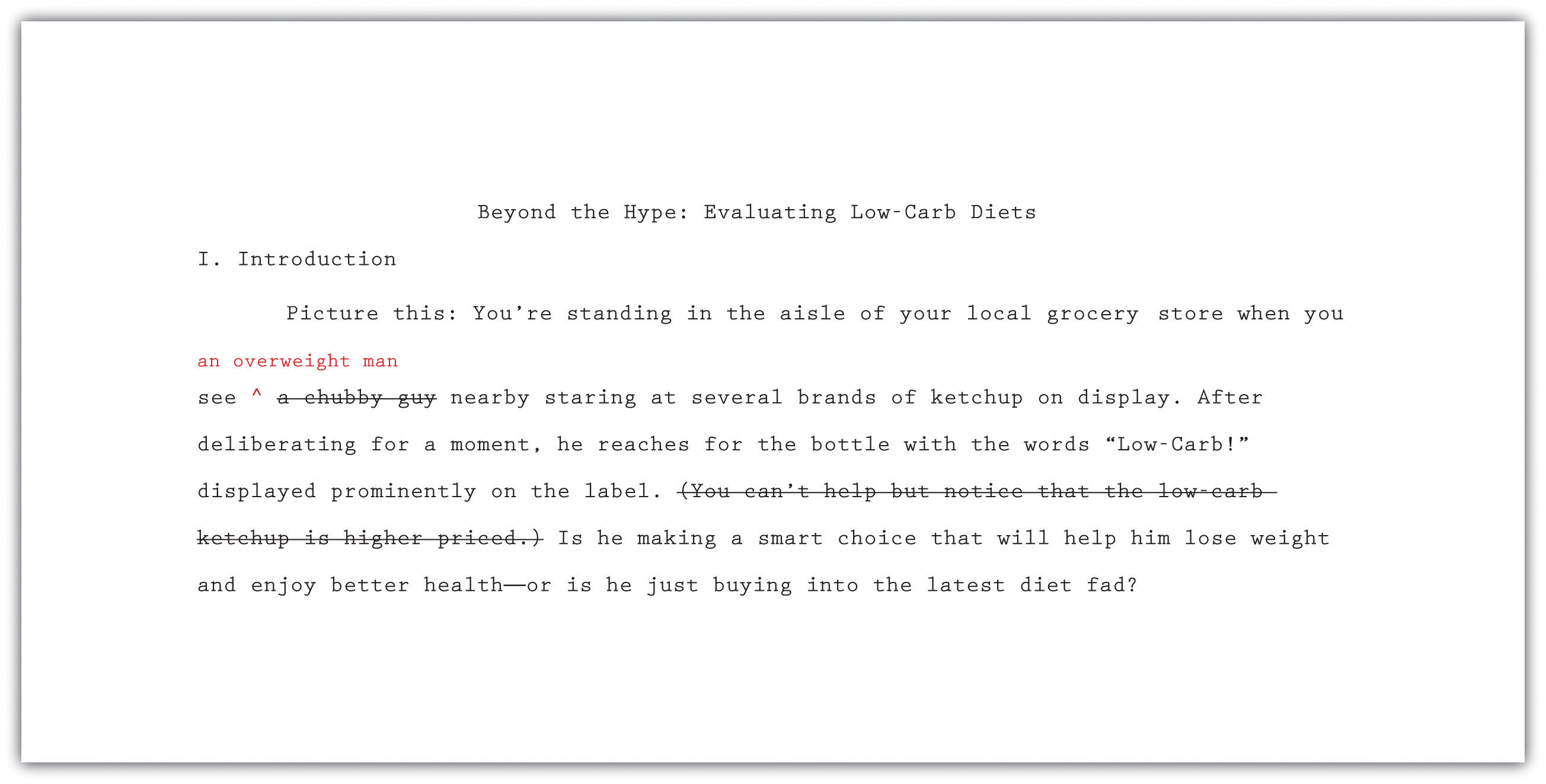

On reviewing his paper, Jorge found that he had generally used an appropriately academic style and tone. However, he noticed one glaring exception—his first paragraph. He realized there were places where his overly informal writing could come across as unserious or, worse, disparaging. Revising his word choice and omitting a humorous aside helped Jorge maintain a consistent tone. Read his revisions.

Using Checklist 12.3, line-edit your paper. You may use either of these techniques:

- Print out a hard copy of your paper, or work with your printout from Note 12.33 “Exercise 1” . Read it line by line. Check for the issues noted on Checklist 12.3, as well as any other aspects of your writing style you have previously identified as areas for improvement. Mark any areas where you notice problems in style or tone, and then take time to rework those sections.

- If you prefer to work with an electronic document, use the menu options in your word-processing program to enlarge the text to 150 or 200 percent of the original size. Make sure the type is large enough that you can focus on only one paragraph at a time. Read the paper line by line as described in step 1. Highlight any areas where you notice problems in style or tone, and then take time to rework those sections.

Please exchange papers with a classmate. On a separate piece of paper, note places where the essay does not seem to flow or you have questions about what was written. Return the essay and compare notes.

Editing Your Paper

After revising your paper to address problems in content or style, you will complete one final editorial review. Perhaps you already have caught and corrected minor mistakes during previous revisions. Nevertheless, give your draft a final edit to make sure it is error-free. Your final edit should focus on two broad areas:

- Errors in grammar, mechanics, usage, and spelling

- Errors in citing and formatting sources

For in-depth information on these two topics, see Chapter 2 “Writing Basics: What Makes a Good Sentence?” and Chapter 13 “APA and MLA Documentation and Formatting” .

Correcting Errors

Given how much work you have put into your research paper, you will want to check for any errors that could distract or confuse your readers. Using the spell-checking feature in your word-processing program can be helpful—but this should not replace a full, careful review of your document. Be sure to check for any errors that may have come up frequently for you in the past. Use Checklist 12.4 to help you as you edit:

Checklist 12.4

Grammar, Mechanics, Punctuation, Usage, and Spelling

- My paper is free of grammatical errors, such as errors in subject-verb agreement and sentence fragments. (For additional guidance on grammar, see Chapter 2 “Writing Basics: What Makes a Good Sentence?” .)

- My paper is free of errors in punctuation and mechanics, such as misplaced commas or incorrectly formatted source titles. (For additional guidance on punctuation and mechanics, see Chapter 3 “Punctuation” .)

- My paper is free of common usage errors, such as alot and alright . (For additional guidance on correct usage, see Chapter 4 “Working with Words: Which Word Is Right?” .)

- My paper is free of spelling errors. I have proofread my paper for spelling in addition to using the spell-checking feature in my word-processing program.

- I have checked my paper for any editing errors that I know I tend to make frequently.

Checking Citations and Formatting

When editing a research paper, it is also important to check that you have cited sources properly and formatted your document according to the specified guidelines. There are two reasons for this. First and foremost, citing sources correctly ensures that you have given proper credit to other people for ideas and information that helped you in your work. Second, using correct formatting establishes your paper as one student’s contribution to the work developed by and for a larger academic community. Increasingly, American Psychological Association (APA) style guidelines are the standard for many academic fields. Modern Language Association (MLA) is also a standard style in many fields. Use Checklist 12.5 to help you check citations and formatting.

Checklist 12.5

Citations and Formatting

- Within the body of my paper, each fact or idea taken from a source is credited to the correct source.

- Each in-text citation includes the source author’s name (or, where applicable, the organization name or source title) and year of publication. I have used the correct format of in-text and parenthetical citations.

- Each source cited in the body of my paper has a corresponding entry in the references section of my paper.

- My references section includes a heading and double-spaced, alphabetized entries.

- Each entry in my references section is indented on the second line and all subsequent lines.

- Each entry in my references section includes all the necessary information for that source type, in the correct sequence and format.

- My paper includes a title page.

- My paper includes a running head.

- The margins of my paper are set at one inch. Text is double spaced and set in a standard 12-point font.

For detailed guidelines on APA and MLA citation and formatting, see Chapter 13 “APA and MLA Documentation and Formatting” .

Following APA or MLA citation and formatting guidelines may require time and effort. However, it is good practice for learning how to follow accepted conventions in any professional field. Many large corporations create a style manual with guidelines for editing and formatting documents produced by that corporation. Employees follow the style manual when creating internal documents and documents for publication.

During the process of revising and editing, Jorge made changes in the content and style of his paper. He also gave the paper a final review to check for overall correctness and, particularly, correct APA or MLA citations and formatting. Read the final draft of his paper.

Key Takeaways

- Organization in a research paper means that the argument proceeds logically from the introduction to the body to the conclusion. It flows logically from one point to the next. When revising a research paper, evaluate the organization of the paper as a whole and the organization of individual paragraphs.

- In a cohesive research paper, the elements of the paper work together smoothly and naturally. When revising a research paper, evaluate its cohesion. In particular, check that information from research is smoothly integrated with your ideas.

- An effective research paper uses a style and tone that are appropriately academic and serious. When revising a research paper, check that the style and tone are consistent throughout.

- Editing a research paper involves checking for errors in grammar, mechanics, punctuation, usage, spelling, citations, and formatting.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

How to Write a Rough Draft for a Research Paper

Before you begin to write your research paper rough draft, you have some decisions to make about format, or how your paper will look. As you write, you have to think about presenting your ideas in a way that makes sense and holds your readers’ interest. After you’ve completed your draft, make sure you’ve cited your sources completely and correctly. And the last thing you’ll need to do is decide on the very first thing readers see—the title.

Following a Research Paper Format

Punctuation.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code.

Many instructors tell their students exactly how their research papers should be formatted—for example, how wide the margins should be, where and how the sources should be listed, and so on. If your teacher has specified a format, be sure you have a list of the rules she or he has established—and follow them! If not, you need to decide on questions of format for yourself. Here are the main formatting issues to consider:

- Should your report be written by hand or typed in a word processing program?

- If you are handwriting, should you write on every line or every other line?

- If you are handwriting, should you use both sides or only one side of the paper?

- If you are typing, should you use single space or double space? For typing, double spacing is standard.

- If you are using a computer, what type style (font) and size should you use? (Twelve-point Times or Times New Roman is standard.)

- What size should the margins be? Margins of 1″ or 1.25″ on each side are standard.

- How long should your report be—how many pages or words?

- Should you include illustrations? Are illustrations optional?

- How should you position your heading (and should it include information other than name, class, and date)?

- Should you include a separate title page?

- Should your bibliography (a list of your sources) appear on a separate page at the end of your report? That is standard.

- Should your bibliography list your sources in alphabetical order by last name of author? That is standard.

- Where should your page numbers appear? The standard position for page numbering is the upper right corner of each page.

If you are using a computer, choose and set up your margin widths, type size and style, and spacing before writing.

Using a Proper Writing Style

Even if you haven’t finished all your research, when you have completed most of your note cards and your outline, it’s time to start writing. Drafting at this stage allows you to see what additional information you need so you can fill it in. As you begin to draft your paper, it’s time to consider your writing style.

A writer’s style is his or her distinctive way of writing. Style is a series of choices—words, sentence length and structure, figures of speech, punctuation, and so on. The style you select for your research paper depends on the following factors:

Before you begin, it is a good idea to again consider the members of your audience:Who are they? What do they know? What style of writing and language will they find most interesting or persuasive? Recognize that although members of your audience may all be of a similar background and educational level, they will not necessarily possess the same knowledge of the subject that you do. Ask yourself:

- How much of the information covered by your research is common knowledge? You want to provide sufficient explanation of unfamiliar concepts but, at the same time, not belabor the obvious.

- What questions will the reader have? Be sure you address all key questions that are essential to the reader’s understanding of your subject.

- How will your reader react to your thesis? This is especially important in a persuasive paper where your goal is to have your readers accept your thesis.

- What kind of information is needed to move your reader to a better understanding of the subject or to agree with your assessment of it? The answers to this question will provide the topics for the paragraphs in the body of your paper.

- What do you want the reader to remember most? This will be the focus of your conclusion.

The answers to these questions will give you a sense of how much background you will need to include about your subject as well as the language and tone of writing that you should use to present it.

Writers have four main purposes:

- to explain (exposition)

- to convince (persuasion)

- to describe (description)

- to tell a story (narration)

Your purpose in your research paper is to persuade or convince. As a result, you’ll select the supporting material (such as details, examples, and quotations) that will best accomplish this purpose. As you write, look for the most convincing examples, the most powerful statistics, the most compelling quotations to suit your purpose.

The tone of a piece of writing is the writer’s attitude toward his or her subject matter. For example, the tone can be angry, bitter, neutral, or formal. The tone depends on your audience and purpose. Since your research paper is being read by educated professionals and your purpose is to persuade, you will use a formal, unbiased tone. The writing won’t condescend to its audience, insult them, or lecture them.

The language used in most academic and professional writing is called “Standard Written English.” It’s the writing you find in magazines such as Newsweek, US News and World Report, and The New Yorker. Such language conforms to the widely established rules of grammar, sentence structure, usage, punctuation, and spelling. It has an objective, learned tone. It’s the language that you’ll use in your research paper.

The Basics of Research Paper Style

The following section covers the basics of research paper writing style: words, sentences, and punctuation.

Write simply and directly . Perhaps you were told to use as many multisyllabic words as possible since “big” words dazzle people. Most of the time, however, big words just set up barriers between you and your audience. Instead of using words for the sake of impressing your readers, write simply and directly.

Select your words carefully to convey your thoughts vividly and precisely. For example, blissful , blithe , cheerful , contented , ecstatic , joyful , and gladdened all mean “happy”—yet each one conveys a different shade of meaning.

Use words that are accurate , suitable , and familiar :

- Accurate words say what you mean.

- Suitable words convey your tone and fit with the other words in the document.

- Familiar words are easy to read and understand.

As you write your research paper, you want words that express the importance of the subject but aren’t stuffy or overblown. Refer to yourself as I if you are involved with the subject, but always keep the focus on the subject rather than on yourself. Remember, this is academic writing, not memoir.

Avoid slang , regional words , and nonstandard diction . Below is a brief list of words that are never correct in academic writing:

- irregardless

Avoid redundant , wordy phrases. Here are some examples:

- honest truth

- past history

- fatally killed

- revert back

- live and breathe

- null and void

- most unique

- cease and desist

- proceed ahead

Always use bias-free language . Use words and phrases that don’t discriminate on the basis of gender, physical condition, age, or race. For instance, avoid using he to refer to both men and women. Never use language that denigrates people or excludes one gender. Watch for phrases that suggest women and men behave in stereotypical ways, such as talkative women . In addition, always try to refer to a group by the term it prefers. Language changes, so stay on the cutting edge. For instance, today the term “Asian” is preferred to “Oriental.”

Effective writing uses sentences of different lengths and types to create variety and interest. Craft your sentences to express your ideas in the best possible way. Here are some guidelines:

- Mix simple, compound, complex, and compound-complex sentences for a more effective style. When your topic is complicated or full of numbers, use simple sentences to aid understanding. Use longer, more complex sentences to show how ideas are linked together and to avoid repetition.

- Select the subject of each sentence based on what you want to emphasize.

- Add adjectives and adverbs to a sentence (when suitable) for emphasis and variety.

- Repeat keywords or ideas for emphasis.

- Use the active voice, not the passive voice.

- Use transitions to link ideas.

Similarly, successful research papers are free of technical errors. Here are some guidelines to review:

- Remember that a period shows a full separation between ideas. For example: The car was in the shop for repair on Friday. I had no transportation to work.

- A comma and a coordinating conjunction (for, and, but, or, yet, so, nor) show the relationships of addition, choice, consequence, contrast, or cause. For example: 1) The car was in the shop for repair on Friday, so I had no transportation to work . 2) The car was in the shop for repair on Friday, but I still made it to work . 3) The car was in the shop for repair on Friday, yet I still made it to work .

- A semicolon shows the second sentence completes the content of the first sentence. The semicolon suggests a link but leaves to the reader to make the connection. For example: The car was in the shop for repair on Friday; I didn’t make it to work .

- A semicolon and a conjunctive adverb (such as nevertheless and however) show the relationship between ideas: addition, consequence, contrast, cause and effect, time, emphasis, or addition. For example: The car was in the shop for repair on Friday; however, I made it to work anyway .

- Using a period between sentences forces a pause and then stresses the conjunctive adverb. For example: The car was in the shop for repair on Friday. But I still made it to work .

Even if you do run a grammar check, be sure to check and double-check your punctuation and grammar as you draft your research paper.

Back to How To Write A Research Paper .

ORDER HIGH QUALITY CUSTOM PAPER

Understanding and solving intractable resource governance problems.

- Conferences and Talks

- Exploring models of electronic wastes governance in the United States and Mexico: Recycling, risk and environmental justice

- The Collaborative Resource Governance Lab (CoReGovLab)

- Water Conflicts in Mexico: A Multi-Method Approach

- Past projects

- Publications and scholarly output

- Research Interests

- Higher education and academia

- Public administration, public policy and public management research

- Research-oriented blog posts

- Stuff about research methods

- Research trajectory

- Publications

- Developing a Writing Practice

- Outlining Papers

- Publishing strategies

- Writing a book manuscript

- Writing a research paper, book chapter or dissertation/thesis chapter

- Everything Notebook

- Literature Reviews

- Note-Taking Techniques

- Organization and Time Management

- Planning Methods and Approaches

- Qualitative Methods, Qualitative Research, Qualitative Analysis

- Reading Notes of Books

- Reading Strategies

- Teaching Public Policy, Public Administration and Public Management

- My Reading Notes of Books on How to Write a Doctoral Dissertation/How to Conduct PhD Research

- Writing a Thesis (Undergraduate or Masters) or a Dissertation (PhD)

- Reading strategies for undergraduates

- Social Media in Academia

- Resources for Job Seekers in the Academic Market

- Writing Groups and Retreats

- Regional Development (Fall 2015)

- State and Local Government (Fall 2015)

- Public Policy Analysis (Fall 2016)

- Regional Development (Fall 2016)

- Public Policy Analysis (Fall 2018)

- Public Policy Analysis (Fall 2019)

- Public Policy Analysis (Spring 2016)

- POLI 351 Environmental Policy and Politics (Summer Session 2011)

- POLI 352 Comparative Politics of Public Policy (Term 2)

- POLI 375A Global Environmental Politics (Term 2)

- POLI 350A Public Policy (Term 2)

- POLI 351 Environmental Policy and Politics (Term 1)

- POLI 332 Latin American Environmental Politics (Term 2, Spring 2012)

- POLI 350A Public Policy (Term 1, Sep-Dec 2011)

- POLI 375A Global Environmental Politics (Term 1, Sep-Dec 2011)

8 sequential steps to write a first rough draft of a research paper from start to finish (relatively quick and easy)

I promised a few weeks ago that I would blog about how I write a paper from start to finish . I was hoping to have screenshots of every stage of my paper writing, but obviously doing my own research, fieldwork and travelling to academic conferences to present papers (and writing those papers in haste!) didn’t allow me to do this in a much more planned manner. So here are 8 tips I use to write a research paper from start to finish.

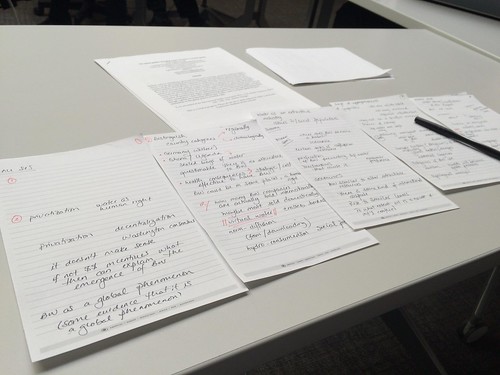

1. Create an outline This tip would be kind of obvious, but I am far from being the first one to suggest that writing an outline allows you to put complex ideas on paper in a sequential, articulate, cohererent form . If you’ve already started writing the paper, then Professor Rachael Cayley’s approach is the best – e.g. create a reverse outline . At any rate, you should have a skeleton of what your paper is going to look like. One way in which I do this is I break down my abstract into the sections that I need to fill out and/or the questions I need to answer to have my paper actually show my full argument. So, the outline comes directly from the paper abstract. What I have found is that often times, my outline doesn’t show the same thing that the paper does at the end of it. That’s fine. At least you answered the questions and/or filled the sections you needed to and refined your abstract and paper on the basis of these responses.

The one sure way in which I know I am going to make progress on a paper is writing the abstract and the introduction. Normally what I do is I expand the abstract and write the introduction from the abstract. I also make sure that I develop the structure of the paper as I write the introduction. Often times, this will change and I will have to come back and redraft this section, but at least I have a basic structure for the paper.

2. Break down the paper into separate documents. I am someone who doesn’t react well to word counts. In fact, I loved a recent blog post by Tseen Khoo entitled “ Your Word Count Means Nothing to Me “. I am disciplined about writing every day for two hours , but I don’t really like the idea of “I write 3,500 words every 1.5 hours”. Some days I write a lot, some days I write much less. And some days, I just simply can’t write ( though I summarize papers and reflect on them during my #AcWri period those days to keep generating text that I might use at some point, particularly research and reading memoranda ).

So what I do instead is, I break the paper down into sections for which I then create separate documents. For example, for my recent paper on environmental mobilizations against Nestlé in British Columbia and in California, I created a separate document for the story around Nestlé in British Columbia and another one for the story on Nestlé in California. To avoid getting frustrated, I just focus on writing on one of the sections at a time.

As I was trying to finish my MPSA 2016 remunicipalizations paper (with a comparative table of 6 cases – Paris, Grenoble, Berlin, Atlanta, Hamilton and Buenos Aires), I got frustrated that I had assembled the paper too early for my liking and therefore I was not sure if I had completely told all the stories. For me, a story is fully told when there is at least 4-6 paragraphs that outline the overall issue and provide some analysis. That’s why at least 4-6 paragraphs would be necessary (history, the issue at hand, why is this issue relevant, what does my theoretical framework say about this particular issue) to fully outline and sketch the story. So, while I recognize that I had assembled the paper early, I used a summary table to ensure that I had already completely told all the stories. This table also helped me finish the paper because I could use the insights gained from this exercise for the analysis section and the conclusions section (see tip 4).

7. Don’t write beyond your physical limits Recently, I finished a book chapter by inserting 3,500 words that I wrote in the first 1.5 hours of the day into a draft that had 3,400 words. So I finished an 8,000 word paper in about 2 or 3 days. Obviously this only works if you’ve already simmered and thought about the paper for a very long time. I had been spinning my wheels for the past few days when I knew that I had made no progress on this paper in the past 4.75 months. This week, I just decided that I needed sleep and I stopped trying to write (yes, I too try to push my limits and do some “spree-writing”) so I went to sleep early. I woke up on Wednesday at 5 am, and by 6:30pm, I had finished the book chapter.

FIVE MONTHS. I was stuck with this stupid chapter for 4.75 of those. This week, my brain woke up and BAM, 3,454 words #GetYourManuscriptOut — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) April 14, 2016

The reality is that academia has this toxic culture of overworking as though it were a badge of honor. But I can’t do that anymore. I used to work 24 hours in a row, sometimes even 36. Right now I can’t push my physical limits and I will not endorse overwork. So I know for a fact that I improved my writing since I started sleeping at a decent hour and at least 6 hours a day. And that’s exactly why I never write beyond my physical limits even if I am not done with the paper and I have a deadline. I prefer to ask for an extension or simply say “No, I can’t write your book chapter/paper/article” because I will no longer push myself beyond my physical limits.

“Being tired isn’t a badge of honor” by @jasonfried – applies to academics and everyone https://t.co/Ld8JcHmps3 pic.twitter.com/RYJ7EIen8n — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) April 14, 2016

8. Assemble the paper 80%-90% into the process When I assemble a paper too early into the process, I end up seeing all the gaps in the paper and this demoralizes me. So now what I do, is I assemble the paper about 80-90% into the process. I assemble the introduction, conclusion, body of the paper and I collect my handwritten notes of what needs to be improved and corrected. And then I go over the paper and figure out if I am missing something. That way, whenever I sit down and work on this paper again, I feel that I am about to be done.

Applying this process helped me complete 3 draft papers (2 for MPSA, 1 book chapter, and two I’m working on) in about 5 weeks, all the while travelling every week and teaching one class every week. This is not to brag, but it’s just to show that if I follow a systematic process, I can move forward even under conditions of relative duress (e.g. when I am travelling). So, every single day I was able to work on research and write for a few hours because I was working every day on a different, single component of my paper and research project. As I have often said, I follow Aunty Acid’s advice: I take life one panic attack at a time .

This is my approach to academic life, my dear friends #AuntieAcid pic.twitter.com/p32UcYehGK — Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) March 6, 2016

You can share this blog post on the following social networks by clicking on their icon.

Posted in academia .

Tagged with academic writing , AcWri , research paper , writing .

By Raul Pacheco-Vega – April 16, 2016

2 Responses

Stay in touch with the conversation, subscribe to the RSS feed for comments on this post .

Thank you for sharing!! Really insightful look into your process – and inspiring to boot. Love point #4 and just learning about #7 the hard way this year….

Continuing the Discussion

[…] that I am transcribing in this blog post. My advice is very similar to what I suggested when I described my process to generate a full first draft of a paper or article in 8 steps. Basically, I write in bits and pieces (memorandums) and then I assemble the entire manuscript once […]

Leave a Reply Cancel Some HTML is OK

Name (required)

Email (required, but never shared)

or, reply to this post via trackback .

About Raul Pacheco-Vega, PhD

Find me online.

My Research Output

- Google Scholar Profile

- Academia.Edu

- ResearchGate

My Social Networks

- Polycentricity Network

Recent Posts

- The value and importance of the pre-writing stage of writing

- My experience teaching residential academic writing workshops

- “State-Sponsored Activism: Bureaucrats and Social Movements in Brazil” – Jessica Rich – my reading notes

- Reading Like a Writer – Francine Prose – my reading notes

- Using the Pacheco-Vega workflows and frameworks to write and/or revise a scholarly book

Recent Comments

- Raul Pacheco-Vega on Online resources to help students summarize journal articles and write critical reviews

- Muhaimin Abdullah on Writing journal articles from a doctoral dissertation

- Muhaimin Abdullah on Writing theoretical frameworks, analytical frameworks and conceptual frameworks

- Joseph G on Using the rhetorical precis for literature reviews and conceptual syntheses

- Alma Rangel on Improving your academic writing: My top 10 tips

Follow me on Twitter:

Proudly powered by WordPress and Carrington .

Carrington Theme by Crowd Favorite

IMAGES

VIDEO