Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

A systematic review of complementary and alternative medicine in oncology: Psychological and physical effects of manipulative and body-based practices

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Laboratoire EA 4136 / INSERM UMR 1219, Team: Handicap Activity Cognition Health (HACH), Bordeaux, France, Univ. Bordeaux, Bordeaux, France

Roles Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Univ. Bordeaux, Bordeaux, France

Roles Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing

- Nicolas Calcagni,

- Kamel Gana,

- Bruno Quintard

- Published: October 17, 2019

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223564

- Reader Comments

Complementary and Alternative Medicines (CAM) are widely used by cancer patients, despite limited evidence of efficacy. Manipulative and body-based practices are some of the most commonly used CAM. This systematic review evaluates their benefits in oncology.

A systematic literature review was carried out with no restriction of language, time, cancer location or type. PubMed, CENTRAL, PsycArticle, PsychInfo, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection and SOCindex were queried. Inclusion criteria were adult cancer patients and randomized controlled trials (RCT) assessing manipulative and body-based complementary practices on psychological and symptom outcomes. Effect size was calculated when applicable.

Of 1624 articles retrieved, 41 articles were included: massage (24), reflexology (11), acupressure (6). Overall, 25 studies showed positive and significant effects on symptom outcomes (versus 9 that did not), especially pain and fatigue. Mixed outcomes were found for quality of life (8 papers finding a significant effect vs. 10 which did not) and mood (14 papers vs. 13). In most studies, there was a high risk of bias with a mean Jadad score of 2, making interpretation of results difficult.

These results seem to indicate that manipulative CAM may be effective on symptom management in cancer. However, more robust methodologies are needed. The methodological requirements of randomized controlled trials are challenging, and more informative results may be provided by more pragmatic study design.

Citation: Calcagni N, Gana K, Quintard B (2019) A systematic review of complementary and alternative medicine in oncology: Psychological and physical effects of manipulative and body-based practices. PLoS ONE 14(10): e0223564. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223564

Editor: Erik Loeffen, Beatrix Children’s Hospital, University Medical Center Groningen, NETHERLANDS

Received: December 27, 2018; Accepted: September 24, 2019; Published: October 17, 2019

Copyright: © 2019 Calcagni et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: This research was funded by the French ‘Site de Recherche Intégrée sur le Cancer - Bordeaux Recherche Intégrée en Oncologie’ (SIRIC – BRIO, https://siric-brio.com ), which brings together multidisciplinary research teams working in synergy to produce new knowledge for the benefit of patients. NC received the funding. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Given the physical and psychological distress induced by cancer treatments, there is consensus on the importance of considering psychosocial features for cancer patients [ 1 – 4 ]. Non-medicated therapies, known as “Complementary and Alternative Medicine” (CAM) [ 5 ], are becoming a more popular supportive care option. Several commonly used therapies are reflexology, osteopathy, or chiropractic care, coming under the heading of ‘manipulative and body-based practices’ [ 6 ]. However, the scientific evidence of their efficacy is still unclear.

The first problem may lie in lack of clarity and evolving definitions of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM). An initial proposal by the World Health Organization defines: “a broad set of health care practices that are not part of that country’s own tradition and are not integrated into the dominant health care system” [ 5 ]. The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) and the Office of Cancer Complementary and Alternative Medicine (OCCAM) further categorize these practices that are not part of standard care into “complementary”: when the non-mainstream practice is used along with conventional medicine; “alternative”: when conventional medicine is replaced by the practice, and “integrative”: when conventional and complementary approaches are combined together in a coordinated way [ 7 – 10 ].

Another emerging term is given by the Collaborative university platform for Evaluating health Prevention and Supportive care Programs (CEPS), which suggests the term of Non-Pharmacological Intervention (NPI), defining NPIs as “non-invasive and non-pharmacological interventions on human health based on science” with an “observable impact on health, quality of life, behavioral and socioeconomic indicators” [ 8 ]. This definition differs from the earlier proposals in that it insists on the scientific approach needed to be labeled as NPI. Several dozen therapies can be gathered under these definitions, such as acupuncture, herbs, reiki, reflexology, homeopathy, meditation, diets, yet there is a lack of consensus on their classifications which vary in length and complexity across countries and authorities [ 7 , 9 – 11 ].

CAM is widely used, especially in the case of cancer, and prevalence is around 37.5% in France, 35.9% in Europe, or 40% in USA [ 12 – 15 ]. Patients hope that CAM may help them in curing the illness, improving their well-being, lessening side-effects of their treatments, improving their immune system to resist cancer and its treatments, or even prolonging their survival [ 11 , 16 , 17 ]. A number of systematic reviews have been conducted to assess the efficacy of CAM [ 15 , 18 – 22 ]. Results from these studies are often mixed; some trials show positive effects of the practices and others show negative results. The fact that most of the studies have low quality methodology with a high risk of bias adds to the uncertainty of their effects. Moreover, many of these systematic reviews incorporate several CAM without distinguishing between them, focus on only one kind of cancer limiting generalization of results, or are outdated. Thus, the efficacy of these CAM approaches has yet to be clearly demonstrated to provide evidence-based recommendations to patients and oncologists.

The primary aim of this review was to systematically identify and collate randomized controlled trials investigating the effects of manipulative and body-based practices in oncological settings, allowing a clearer assessment of their efficacy. The secondary objective was to identify which specific manipulative and body-based practices are used in oncology. We chose to focus on these techniques because as they are based on touch, they could stimulate a sense of wellness and pleasure on a body that is hurt by the illness and its invasive treatment [ 23 ].

Methods and materials

Eligibility criteria, population..

Studies including adult (≥ 18 years) patients with a diagnosis of cancer, with no limitations regarding time since diagnosis or cancer location were included.

Intervention.

CAM interventions in oncology were included if they were associated with manipulative and body-based practices such as massage, reflexology, chiropractic, osteopathy, naprapthy and shiatsu/tui na/acupressure [ 24 – 30 ].

Comparison group.

Randomized Controlled Trials (RCT) that featured any comparison control group (usual care, placebo, sham practice, visit by staff) were selected. Any trials involving self-administered and/or tool-assisted interventions only (use of acupressure bands without the intervention of a practitioner, for example) were excluded.

Studies featuring quality of life, psychosocial, symptoms and side-effect-related outcomes were included, based on the rationale that the main expectation of people using CAM was to improve well-being and to reduce/manage symptoms. Outcomes varied from quality of life to mood (anxiety, depression, stress) and symptom management (nausea, fatigue, pain).

Study design.

The search was restricted to RCTs because they represent the gold standard by which health care professionals make decisions about treatment effectiveness. All RCT designs were accepted (parallel, cross-over, cluster), to ensure full coverage.

Information sources

We queried the following electronic databases: PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), PsycArticle, Psychinfo, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection and SOCindex with no limitations for publication date nor language. The search was last updated on September 2018.

Search algorithm

Keywords included successively in all databases were: massag* AND cancer AND trial; reflexolog* OR foot massag* OR feet massag* AND cancer AND trial; chiropract* AND cancer AND trial; osteopath* AND cancer AND trial; naprapath* AND cancer AND trial; acupressure AND cancer AND trial. We subsequently withdrew the command “AND trial” for Cochrane CENTRAL, as we narrowed the results to “Trials”, excluding Cochrane reviews, Other reviews, Methods Studies, Technology Assessments, Economic Evaluations and Cochrane Groups. Shiatsu and Tui Na practices were not directly included in our search strategy because acupressure—which shares the same principles with these techniques—is more represented in the scientific literature [ 31 ]. The first author performed all databases searches.

Study selection

Articles were systematically screened on their title and abstract, which had to contain words linked to cancer or oncology, “trial”, and words linked to manipulative and body-based practices (such as reflexology, massage, acupressure, shiatsu…) to be included in the full review of the article. Studies were included in the final review when criteria of eligibility were confirmed after reading the whole article: RCT design, adequate population, relevant intervention and outcome. They were excluded if the participants were below the age of 18 (irrelevant population), the intervention was not linked to manipulative practice or was only self-administered or tool-assisted or mixed with other techniques (irrelevant intervention). PRISMA guidelines were followed throughout the present review [ 32 ].

Data items and collection process

Information collected from the selected studies was chosen according to the procedure initiated by McVicar et al. [ 20 ]. For each paper, information about setting of the studies (year of publication, country of publication, kind of cancer, intervention used, dose and duration of the sessions, percentage of female participant, sample size), method used (design of the RCT, degree of blinding, randomization method, control strategy) and results (significant outcome, non-significant outcomes, and where possible mean of each group before and after intervention) had to be systematically noted. These data were manually identified in each study and noted on an excel file that was used for calculations. Dual independent selection, inclusion, data extraction and comparison were performed by NC and BQ for the first 20 studies of each databases. KG was the referee in case of doubts or disagreement. If consensus was reached on these 20 studies, the rest of selection, exclusions and data extractions were shared between NC and BQ in a single fashion.

Summary measure

Simple descriptive statistics and qualitative content analysis were used. As our studies showed clinical heterogeneity in terms of outcomes, kind of cancer, interventions, design, control strategy, implementation and timing of evaluations, it was impractical to run quantitative analysis for a meta-review. As such, we strengthened our analysis by calculating, where possible, the effect size and the correlated 95% Confidence Interval (95% CI) [ 33 ]. Effect sizes (Standardized Mean Difference) were calculated based on means (M) and standard deviations (SD) of intervention and control groups only [ 34 ]. When a study measured the same variable more than two times, a pooled effect size was obtained using the mean of a “meta-analysis-like” method with random effects model using Exploratory Software for Confidence Intervals (ESCI) [ 35 ]. Effect size was calculated before intervention (to verify absence of group effect before intervention) and after intervention. NC and KG performed the qualitative and quantitative analyses of the study.

Risk of bias

The Jadad scale, which is a commonly used three-item five-point quality scale, was used to rate independently the quality of the trials and to allocate a score of between zero (very poor) and five (rigorous) [ 36 ]. Two points were given if the research used appropriate randomization (at least randomization by block with random variation). Two other points were allocated if the authors reported the use of double blinding. A last point was allocated if authors integrated description of the withdrawals in their study. To maximize study inclusions, we did not use a minimum cut-off score as an inclusion criterion.

A total of 1,624 citations were found by our search strategy, including 526 through PsycINFO, PsychArticle, Psychology and Behavorial Sciences Collection and Socindex databases, 695 through CENTRAL and 403 through PubMed ( Fig 1 ). After excluding duplicates (n = 88), 1536 records were screened (titles and abstracts), which led to the exclusion of 1371 studies. Thus, 165 full-text articles were assessed, of which 127 were excluded (see Fig 1 for explanations), leaving 38 studies. A further three were added after screening the references of the reviewed articles giving a total of 41 studies for final qualitative synthesis.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223564.g001

Overall summary

Over half of the studies related to massage ( Table 1 ). Included trials were mainly led in high income countries (European or North American countries, n = 24) and in low income countries (Asia, n = 17). A total of 3044 participants were included across all studies. The median Jadad score was 2 out of 5 (range from 0 to 5), implying inconstant quality of design and high risk of bias in methods across studies. Most studies failed to present double blinding and adequate randomization. As several studies showed both significant and non-significant results, or included several of the selected outcomes (symptoms, mood and QOL), numbers given below are naturally unbalanced. Significant symptom improvement (fatigue, pain, sleep, etc.) after intervention was observed in 25 of the 29 studies measuring symptom outcomes. Balanced results were observed for mood outcomes with 14 of the 24 studies showing significant improvements. Finally, 10 of the 15 studies about quality of life did not find any significant differences in quality of life after interventions ( Table 1 ). It was possible to calculate effect size for 18 studies. Of these papers, 16 studies showed “problematic” effect sizes before the intervention, supporting the reliability of the intervention evaluation by assessing the lack of between-group effects before intervention. After intervention, 15 out of 18 studies showed a significant non-problematic effect. Across all interventions, the largest effect sizes were found on symptoms. Indeed, 12 effect size indicators were available after calculation, and 8 of them were large (≥ 0.8), 3 were moderate (≥0.5) and 1 was small (≥ 0.2) (Tables 2 , 3 and 4 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223564.t001

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223564.t002

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223564.t003

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223564.t004

Massage therapy results (n = 24)

Massage studies have been mainly led in high-income countries (United States n = 8; Germany n = 3; United Kingdom n = 2; Sweden n = 2; Quebec n = 1; Spain n = 1), and fewer in Asian countries (Iran n = 3; Turkey, Japan, China and Taiwan n = 1 each one). Mean age of participants varied from 34.5 to 71.5 (M = 55.9, SD = 7.9). 70% of the studies included mostly female participants (50% female-only participants, 20% more than half participants). In these studies, only six used a control strategy which featured a “placebo” intervention (a simple massage or touch) or used more than two groups. Thirteen studies featured mainly a simple control group/ usual care (54%), and five an attention group “visit by staff” (23%). Interventions were delivered by a professional therapist in 58% of the studies, while 30% of the interventions were delivered by trained nurses or authors. Number of interventions ranged from 1 to 15 sessions (M = 7.1, SD = 4.5), and length varied from 10 to 60 minutes each session (M = 29.8, SD = 12.9). Details of these studies can be found in Table 2 .

Fifteen of the 24 studies showed an improvement in symptoms in the intervention group. Nevertheless, most of these studies had small samples and a Jadad score of 0 to 3. The most trustworthy trial, with a Jadad score of 5, showed improvements across time in pain levels, both clinically and statistically (F = 61.17, p = 0.000) [ 51 ].

Concerning mood outcomes, four studies showed a significant decrease in anger, anxiety, depression, stress and mood disturbance (anger, anxious depression) in people receiving massage compared to the control group [ 39 ; 48 , 50 , 55 ]. Nevertheless, these previous studies feature a high risk of bias. A robust study on patients with breast cancer showed that patients receiving massage therapy had a significant improvement in clinical anxiety and depression at six weeks post randomization [ 44 ].

Reflexology results (n = 11)

In reflexology studies (n = 11), the mean age of the participants ranged from 51 to 74 (M = 59.2, SD = 6.1). As for massage studies, they were mainly led in high-income countries (United Sates n = 4, United Kingdom n = 3 vs. Turkey n = 3 and Taiwan n = 1). 81% of the studies included mostly female participants (36% female-only participants, 45% more than half participants). Five studies featured at least a placebo intervention like sham reflexology or more than two groups (one “placebo” intervention and one control group/usual care). Six studies featured control group only. Interventions were delivered by reflexologists in 7 on11 studies, by trained authors in 2. Number of sessions ranged from 2 to 84 (M = 12.4, SD = 23.9) and length varied from 20–60 minutes (M = 32.5, SD = 11.4).

Seven studies showed improvement on symptoms, although most had a high risk of bias (Jadad score ranging from 1 to 2). Both studies of Wyatt et al. carried strong randomized controlled trials evaluating reflexology for breast cancer patients (large sample size, Jadad score of 4). The first one [ 66 ] focused on breast cancer (N = 243) comparing reflexology to lay foot manipulation and a control group with three waves of data collection (prior to intervention, 1 week after intervention and six weeks after the intervention). No differences were found on pain and nausea, but a significant reduction in dyspnea severity was found compared to lay foot manipulation group (p = .02) and control group (p < .01). The second one found a clearer and stronger significant decrease of symptom severity (p = .02) and symptom interference (p < .01) over the 11 weeks of the trials in the reflexology group compared to the control group (N = 180). These symptoms include pain, fatigue, nausea, disturbed sleep, distress, shortness of breath, difficulty remembering, decreased appetite, drowsiness, dry mouth, sadness, vomiting and numbness/tingling. A final study [ 65 ] with a Jadad score of 5 (N = 61) demonstrated that digestive cancer patients in the intervention group reported less pain over time and that their consumption of opioid analgesics decreased compared to the control group. The same authors also demonstrated a higher decrease in anxiety in the intervention group than in the control group (p < .05). This is one of the only studies that reported a benefit of reflexology on anxiety, with a previously cited study [ 64 ]. For more details, see Table 3 .

Acupressure results (n = 6)

Acupressure studies were exclusively carried out in countries in Asia (Iran n = 3; Turkey n = 1; China n = 1; Taiwan n = 1). The mean age of participants varied from 34.5 to 71.5 (M = 51.7, SD = 6.5). Around 50% of the studies featured female participants mainly (1 study on 6 female only-participants, 2 studies on 6 more than half participants. 4 of 6 studies used a control strategy which featured a “sham acupressure” intervention. Interventions were delivered by a professional therapist in only two studies, while the rest of the interventions were led by researchers. Dose of the interventions ranged from 3 to 36 sessions (M = 13, SD = 13.4), and length varied from 8 to 30 minutes each session (M = 17, SD = 9.8).

Three studies argued in favor of a positive effect of acupressure on symptoms, of which one trial with a perfect Jadad score and high number of participants shows a strong effect on pain [ 76 ]. All three studies evaluating anxiety highlighted a beneficial effect of acupressure ( Table 4 ).

The aim of this study was to achieve a global understanding of the effects of manipulative and body-based therapies as alternative and integrative therapies in oncology. First of all, although chiropractic and osteopathy are widely used by cancer patients and their use is often recommended on cancer websites [ 13 , 78 ], our systematic review did not find any trials on chiropractic and osteopathy. This result is consistent with the findings of Alcantar et al. [ 78 ] who showed in their systematic review of chiropractics in oncology in 2012 that most papers were based on survey and case discussions only. Further studies are needed to evaluate these practices by randomized trials with cancer patients. Most of the participants in the 41 studies were women. This result is explained by the majority of studies focusing on breast cancer. A systematic review of CAM use in oncology highlights the fact that gender is one of the several dominant characteristics associated with CAM use, with women resorting more to CAM than men [ 79 ]. It has also been suggested that women suffer more from chronic illnesses and use healthcare more extensively than men [ 80 ]. In that respect, it would be advisable to promote manipulative and body-based practice studies alongside males to gain a more extensive knowledge.

Our review showed that manipulative and body-based practices tended to offer positive effects on cancer symptoms. All four studies with the highest quality methodology (Jadad score = 5) showed large effects on pain and/or anxiety after interventions in reflexology, massage or acupressure [ 51 , 65 , 72 , 76 ] but most of the calculated effect sizes above were pooled from different measures of time, denying arbitrarily the possibility of a delayed or cumulated effect over time. Pain and fatigue seemed to be the main symptoms positively affected by the interventions. Assumptions about the mechanisms underlying the efficacy of massage or reflexology range from biological explanation (increase of blood flow and lymph, influence of the autonomic nervous system, stimulation of release of endogenous opiates) to energy-based explanations (removing energy blockages, ensuring recirculation in the blocked areas, increase in the energy level) [ 31 , 39 , 65 , 69 ]. Nevertheless, as these practices are based on touch, it may be hard to determine whether the therapeutic effect is linked to the specificities of the practice or to the attention through human touch and massage-like manipulation [ 23 ].

Unfortunately, less than half of the studies used a placebo group to assess the interventions. This is most certainly due to the cost of implementing placebo versus intervention designs, as well as the difficulties in designing adequate and convincing placebo interventions of manual therapies. In addition, our findings show the lack of convincing method, as most of the studies fail to report adequate blinding and randomization. This is consistent with previous reviews of literature evaluating body-based practices [ 15 , 18 – 22 , 81 – 83 ], which suggested that even though most of the studies tend to find positive effects of massage or reflexology on symptoms in cancer, the heterogeneity of methods, the small sample sizes and the high risk of bias confound the reading of the results and prevent us from drawing a clear interpretation. As such, these previous reviews called for supplementary studies with stronger methods to reduce bias. Recent studies have flourished [ 55 – 60 , 68 – 71 , 74 – 77 ], and yet their methodologies are still affected by a high risk of bias, showing the difficulties involved in leading strong RCTs with non-pharmaceutical interventions. Further randomized controlled trials are still needed to clear remaining doubts, and these trials should be supplied with large samples, adequate randomization and appropriate blinding. Ideally, those trials should be multi-centric, and tested interventions should be administered by several different practitioners, which would be a more truthful representation of CAM.

On another hand, even though RCT is arguably the most powerful study design to assess the efficacy of an intervention, there is still some limits to their uses. Research on chronic diseases is already complex as participants are weakened, difficult to access, and have a high risk of attrition. The high cost of RCTs is well known too: a strict approach is necessary to respect the reproducibility of the results. The price is a high cost of time, funds, and severe criteria of inclusion/exclusion that sacrifice external validity for internal validity [ 84 ]. Thus, different methods of appraisal may be beneficial and complementary to RCTs. Price et al. suggest resorting to “real life” studies when RCTs show their limits [ 84 ]. Thus, observational studies (cross-sectional, cohort,) and pragmatic trials (real-life context of clinic) could prove complementary when assessing questions that are “unanswered or unanswerable” by RCT, especially in CAM [ 85 ]. Another interesting experimental design is the single-case research design. According to Smith’s literature review of the single-case design, this is one of the most cost-effective and efficient procedures to experimentally test the effect of an intervention [ 86 ]. Such design, with adequate replication across different participants and different locations, could prove to be a valuable asset in evaluating an intervention.

Finally, the result of this review must be discussed in the context of a recent observational cohort study that found that cancer patients who received CAM were more likely to refuse or delay conventional treatment and to have a two-fold higher risk of death, making use of CAM a mortality risk [ 87 ]. Although the authors mention several limitations (survival difference could be mediated by adherence to conventional therapies, inclusion of many different kind of CAM prevents the possibility to discuss of any specific type of CAM), their study highlights the importance of caution and robust methodology when researching or recommending CAM.

Clinical implications

We believe that this review provides a starting point for a specific and sound discussion about manipulative CAM on cancer patients, as it seems that they could be beneficial for symptoms management in cancer. This study could help physicians, oncologists and their patients make informed choices about their care. Nevertheless, no study evaluated differences in survival rates with patients using this specific kind of CAM and doubts persist. In that respect, we advise that patients with cancer who are interested in receiving this type of CAM should use them in a complementary way, discuss about it with their physicians and be warned of the lethal dangers of neglecting conventional treatments.

Study limitations

Our findings should be considered keeping in mind several limitations. Firstly, although we investigated the use of CAM in all cancers, most of the studies only included breast cancer. Secondly, we tried to discriminate results by practice. However, the subgroup of massage therapy studies had high heterogeneity, as it included different methods of massage therapy. Sagar, Dryden and Wong [ 31 ] discriminate massage technique by two main branches, including many kinds of massage (Swedish, Trigger point, Neuromuscular, Craniosacral therapy). In our work, we did not go to such lengths and included all massages in the same group. Another limitation is that we did not register our protocol on the database PROSPERO. Unfortunately, our data extraction process was already finished by the time we learnt about PROSPERO. Another limit lies in the tool we used to assess the quality of trials. Although the Jadad scale is one of the most used quality assessment scale, it is also a scale that is considered lacking (over-simplistic, too much emphasize on blinding, low agreement between raters, no assessment of allocation concealment) [ 88 , 89 ]. As such, future researches evaluating RCTs should rely on more solid, complete and recent assessment tool, as the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) [ 90 , 91 ]. Moreover, we did not carry out meta-analysis because of the high heterogeneity of included studies, and thus crucial information are missing, such as forest plot, publication bias, aggregated effect size, and more importantly subgroup analysis that could have given precious details on which intervention would work better on which outcome. Although no formal meta-analysis was possible, additional tools could have been used to strengthen our study, such as the albatross plot, which is designed for the report of diversely reported studies [ 92 ]. Unfortunately, this tool is relatively new and only accessible yet on the software STATA. No studies about osteopathy, chiropractic or naprapathy could be found, preventing us to draw an exhaustive conclusion on Manipulative and Body-Based Practice. On another note, the process of selection, inclusion/exclusion of papers, and data extraction/comparison was only semi-dual and independent, as it was performed on the first 20 studies of each databases. Even if consensus was easily reached between the two independent collectors, there are still risks that the selection of some studies and data extraction may have been biased, as the process was not fully independently verified by both collectors. Finally, this systematic review is incomplete, in that we could not access to the full text of 4 identified articles.

Of 41 studies, including 29 of which assess symptoms, a significant improvement of symptoms was found in 25 studies. The evidence for improvements in cancer symptom management was stronger than for improvements in mood or quality of life. Nevertheless, heterogeneity and weaknesses in the methods used prevents any firm conclusions and cancer patients interested in CAM should be advised to use them responsibly and avoid stopping conventional treatment for their own safety. Further trials are needed to gain a comprehensive knowledge of their effects. These studies will require robust methodology that is onerous and difficult to attain, requiring substantial financial support over time. More rigorous RCTs are needed, and other experimental designs that could prove to be complementary are available.

Supporting information

S1 file. data file of the study..

This table contains all the data used for the narrative review.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223564.s001

S2 File. PRISMA document.

This file contains the references of the pages according to PRISMA Statement.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223564.s002

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the French ‘Site de Recherche Intégrée sur le Cancer—Bordeaux Recherche Intégrée en Oncologie’ (SIRIC—BRIO), which brings together multidisciplinary research teams working in synergy to produce new knowledge for the benefit of patients.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- PubMed/NCBI

- 5. About us [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2018 [cited 5 April 2018]. http://www.who.int/traditional-complementary-integrative-medicine/about/en/2

- 7. Complementary, Alternative, or Integrative Health: What’s In a Name? [Internet]. NCCIH. 2018 [cited 5 April 2018]. https://nccih.nih.gov/health/integrative-health

- 8. Plateforme CEPS: Ontologie [Internet]. Plateformeceps.univ-montp3.fr. 2018 [cited 19 June 2018]. https://plateformeceps.www.univ-montp3.fr/fr/nos-services/ontologie

- 9. Haute Autorité de Santé. Développement de la prescription de thérapeutiques non médicamenteuses validées. Paris: HAS Edition; 2011

- 10. Health Information | OCCAM [Internet]. Cam.cancer.gov. 2018 [cited 5 April 2018]. https://cam.cancer.gov/health_information/about_cam.htm

- 24. reflexology [Internet]. TheFreeDictionary.com. 2018 [cited 6 March 2018]. https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/reflexology

- 25. chiropractic [Internet]. TheFreeDictionary.com. 2018 [Cited 6 March 2018]. https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/chiropractic

- 26. osteopathy [Internet]. TheFreeDictionary.com. 2018 [Cited 6 March 2018]. https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/osteopathy

- 27. naprapathy [Internet]. TheFreeDictionary.com. 2018 [Cited 6 March 2018]. https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/naprapathy

- 28. shiatsu [Internet]. TheFreeDictionary.com. 2018 [Cited 6 March 2018]. https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/shiatsu

- 29. tui na. [Internet]. TheFreeDictionary.com. 2018 [Cited 6 March 2018]. https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/tui+na

- 30. acupressure [Internet]. TheFreeDictionary.com. 2018 [Cited 6 March 2018]. https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/acupressure

- 33. Wilson D. Effect Size Calculator [Internet]. Campbellcollaboration.org. 2018 [cited 16 April 2018]. Available from: https://www.campbellcollaboration.org/escalc/html/EffectSizeCalculator-SMD-main.php

- 35. Cumming G, Calin-Jageman R. Introduction to the new statistics. New York: Routledge; 2017.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Complementary and alternative therapies in skin cancer: A literature review of biologically active compounds.

Leonel hidalgo , md, cristóbal saldías-fuentes , md, karina carrasco , rdn, allan c halpern , md, jun j mao , md, cristian navarrete-dechent , md..

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Authorship Contributions:

(1) Acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data.

(2) Drafting and revising the article.

(3) Final approval of the version to be published.

Corresponding author: Cristian Navarrete-Dechent, MD, Department of Dermatology, Escuela de Medicina, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Diagonal Paraguay 362, 6th floor, Santiago, Chile 8330077, Phone: +56-2-2435 3574, [email protected]

Issue date 2022 Nov.

Introduction:

Complementary and alternative medicine or therapies (CAM) are frequently used by skin cancers patients. Patient’s self-administration of CAM in melanoma can reach up to 40–50%. CAMs such as botanical agents, phytochemicals, herbal formulas (“black salve”) and cannabinoids, among others, have been described in skin cancer patients.

To acknowledge the different CAM for skin cancers through the current evidence, focusing on biologically active CAM rather than mind-body approaches.

We searched MEDLINE database for articles published through July 2022, regardless of study design.

Of all CAMs, phytochemicals have the best in vitro evidence supporting efficacy against skin cancer including melanoma; however, to date, none have proved efficacy on human patients. Of the phytochemicals, Curcumin is the most widely studied. Several findings support Curcumin efficacy in vitro through various molecular pathways, although most studies are in the preliminary phase. In addition, the use of alternative therapies is not exempt of risks: physicians should be aware of their adverse effects, interactions with standard treatments, and possible complications arising from CAM usage.

Conclusion:

There is emerging evidence for CAM use in skin cancer, but no human clinical trials support the effectiveness of any CAM in the treatment of skin cancer to date. Nevertheless, patients worldwide frequently use CAM, and physicians should educate themselves on currently available CAMs.

Keywords: skin cancer, melanoma, non-melanoma skin cancer, complementary therapy, complementary and alternative medicine

Skin cancer is the most frequent malignancy in humans. Both melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer (NSMC) have a growing incidence and relatively stable mortality. Dermatology patients are referring a growing interest in complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) therapies. 1 The National Institute of Health (NIH): National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health defines CAM as “a group of diverse medical and health care practices and products that are not presently considered to be part of conventional medicine”. 1 The use of CAM is a growing phenomenon, and even some (like ‘Kampo medicines’) are covered by health insurances. A survey of 400 directors of private clinics of Japan reported that dermatology was the third medical specialty that prescribed ‘Kampo medicines’ more frequently. 2 Dietary supplements (other than vitamins and minerals) are the most commonly used CAM, followed by mind-body approaches (e.g., deep-breathing exercises and acupuncture, among others). 1 , 3 It has been reported that up to 85% of dermatology patients use CAM at some point, more commonly older women. 1 CAM data use in skin cancer patients is scarce with most information coming from melanoma patients. It has been reported that ~20% of NMSC patients 4 and 40–50% of melanoma patients have used CAM at some point, especially on those with advanced disease. 5

Trust in conventional medicine and compliance to physician’s suggestions showed no difference between CAM users and non-users; however, the feeling of less emotional support from the medical team was significantly higher in the conventional medicine group. 5 In a study, the largest source of information reported by CAM users was print media, family and friends, physicians, and the internet. 3 However, there are reliable resources for finding information regarding complementary health approaches that could be useful to clinicians ( Table 1 ). Herein we performed a literature review on different CAMs for skin cancer. We focused solely on biologically active CAM rather than mind-body approaches. Our objective was to create a resource for dermatologists on different CAMs reported on skin cancer patients.

Recommended Internet resources for integrative oncology. Modified from Lopez, et al. 50

We searched MEDLINE database for articles published through July 2022, using the keywords: (“melanoma” or “nonmelanoma” or “non-melanoma” or “basal cell carcinoma” or “squamous cell carcinoma”) AND (“cutaneous” or “skin” or “skin cancer” AND “complementary therapy” or “complementary medicine” or “alternative therapy” or “alternative medicine” or “non-traditional medicine” or “non-classical medicine”). References within retrieved articles were also reviewed to identify potentially missed studies. We included all studies published to date, in English and/or Spanish, regardless of study design. Exclusion criteria were languages other than English or Spanish and unavailability of the full article. Duplicates were reviewed and excluded.

I. Complementary and alternative therapies in non-melanoma skin cancer:

Despite 18% of patients with NMSC reported any CAM use, only 1% used it as a primary treatment (alternative use). 4 Herein we discuss those with reported outcomes or clinical relevance. No studies on CAM use on systemic/metastatic NMSC were found. Table 2 summarizes the findings.

Summary of complementary and alternative therapies evaluated for non-melanoma skin cancer with most available evidence.

Level of evidence based on www.ebmconsult.com/articles/levels-of-evidence-and-recommendations

1. Botanical agents (herbs):

Botanical agents or “herbs” is used to refer to the whole plant without extraction of the active substances. The active substances of botanical agents are named “Phytochemicals”. The biologic effect of a botanical agent mainly comes from its “phytochemicals”, but it is not limited to it as other components might have relevant effects. Botanical agents have some biological activity in NSMC, mostly in murine models. Botanical agents with proven biological effect on skin tumors include: Goldenseal ( Hydrastis canadensis ), 6 pond apple ( Annona glabra ), 7 bitter melon ( Momordica charantia ), 8 ginger ( Zingiber officinale ), 6 frankincense ( Boswellia serrata ), 9 and willow-tree bark ( Salix caprea) . 6 The glycoalkaloids from Sodom apple plant ( Solanum sodomaeum ) have shown efficacy on basal cell carcinoma (BCC), squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), keratoacanthomas, and actinic keratoses when used topically (cream) in humans. 6 Plants of the genus Gelsemium showed growth reduction of topical carcinogens induced papilloma and skin cancer in mice. 10 Polypodium leucotomos has been shown to increase the efficacy of photodynamic therapy in the treatment of actinic keratosis in humans. 11 Some botanical agents showed photoprotective effects against ultraviolet radiation (UVR), such as red clover flowers ( Trifolium pretense ), 6 flower of Orpheus ( Haberlea rhodopensis ), grape seed extract, 12 green tea, 12 golden polypody ( Polypodium leucotomos) , 11 and ground pine ( Lycopodium clavatum) . 13

1.1. Phytochemicals:

Phytochemicals can modulate multiple biochemical pathways involved in carcinogenesis and can protect cells from damage from free radicals and ultraviolet radiation (UVR). The most relevant type of phytochemicals with anticancer activity are polyphenols, particularly flavonoids, mainly from parsley and celery.

Those with activity in skin tumors and NMSC are resveratrol, 14 cryptolepine, apigenin, 13 and curcumin (Diferuloylmethane). 15 Curcumin was particularly evaluated for SCC. A phase I trial in humans demonstrated that 8000 mg/day curcumin were non-toxic when taken orally for 3 months, and suggested biologic effect in premalignant lesions, including arsenical Bowen’s disease and oral leukoplakia. 16 Phytochemicals with photoprotective activity include silibinin 12 and curcumin.

Curcuminoids:

Curcuminoids are a spice with a yellow color extracted from the roots of the Curcuma longa herb (Turmeric), which belongs to the ginger family. Curcumin is also known as ‘Golden spice’ because of its yellow color found in curry powder. 15 Curcuminoids consist of diferuloylmethane (curcumin), desmethoxycurcumin, and bisdemethoxycurcumin. 15 A study in human oral squamous cell carcinoma (HNO97 cell line) showed inhibition in proliferation, morphological changes (apoptosis-like), alterations in cell cycle distribution, and DNA damage. 15 Also investigators found apoptosis induction and suppression of colony-forming ability in a time-dependent manner. 15

Silymarin/Silibinin

Silymarin is isolated from the seed of milk thistle ( Silybum marianum , Astteraceae family), which is an annual or biennial Mediterranean native herb. 12 Silibinin is a constituent of silymarin. Investigators found protective effect of silbinin against UVB induced-photocarcinogenesis. Silbinin accelerated the removal of UVB-induced DNA damage products and reduction of tumor number, multiplicity, and volume in p53+/+ mice. 12 They also reported a silbinin effect against UVB-induced genomic instability; inhibitory effect against skin SCC/BCC growth and proliferation; induction of apoptotic cell death of skin epidermal cells after UVB exposure; inhibitory effect on molecular expression and activation of inflammatory molecules and oxidative pathways (essential in tumorigenesis); and a inhibitory effect against drug-resistant BCC cells (via targetin EGFR/AKT and Hedghog pathway). 12

Cannabinoids:

Cannabinoid receptors are expressed in both NMSC and melanoma. 17 Studies have shown in vivo and in vitro effects on NMSC. 17 In mice, local administration of cannabinoids prevented growth and vascularization of malignant epidermal tumor cells. 17 Anandamide, an endocannabinoid, may be elevated in skin tumor cells, leading to endocannabinoid-induced apoptosis and tumor cells death. 17 No study has been performed in humans, yet. Furthermore, cannabinoids may have immunosuppressive potential and tumor promoting effects. 18

2. Herbal formulas:

Most of the preparations found on the internet are herbal ‘formulas’ of mixed compounds, including zinc chloride, urea, apricot pits, bloodroot and goldenseal. 6 Of these, escharotic agents are the most notorious, with corrosive properties that produce eschars and scarring. The most frequently used escharotic agent is “black salve”. 19

2.1. “Black salve”:

“Black salve” paste has been widely promoted for its supposed ability to eradicate BCC through topical application on social media and online forums. 19 The composition of “black salve” varies, but it usually includes zinc chloride, and powdered bloodroot from Sanguinaria canadensis . Bloodroot probably inhibits nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-kB), inducing selective apoptosis of cancer cells in in vitro . 19 Histopathological analysis showed scarring, granulomatous responses, extensive necrosis, and suppurative inflammation. 20 “Black salve” treatment efficacy for BCC varies, from complete remission with no residual tumor on biopsy to residual infiltrating BCC. 20 The latter is found more frequently, and moreover, the resulting ulcer from escharotics can last up to 6 months. 20 As escharotics appear to work on the base of direct tissue destruction, the efficacy of “black salve” depends on the extent of the tumor relative to the amount applied.

II. Complementary and alternative therapies in melanoma:

The most frequent CAM reported among melanoma patients are dietary supplements. 3 Reported satisfaction is less than 50% in melanoma patients; mind-body alternatives have shown higher satisfaction rates. 3 Interestingly, some research has evaluated its potential role on systemic/metastatic disease. Table 3 summarizes the findings.

Summary of complementary and alternative therapies evaluated for melanoma skin cancer with most available evidence.

Melanoma models have shown anticancer effect of multiple botanical agents through diverse molecular pathways: Tea tree oil ( Melaleuca alternifolia ), 6 slippery elm ( Ulmus pumila) , chaparral ( Larrea tridentata ), 21 Alpinia galanga , 22 flower buds of Henna ( Lawsonia inermis ), 23 young green barley ( Hordeum vulgare L .), 24 the desert plant Anastatica hierochuntica , 25 homeopathic mother tincture ( Phytolacca decandra) , 26 gurmar or woody climber tree ( Gymnema sylvestre) , 27 Hibiscus rosa-sinensis flower extract, 28 Lingzhi ( Ganoderma lucidum) , 29 and yellow jessamine ( Gelsemium sempervirens) . 10 Ferula species mixed with derivatives of curcumin showed no cytotoxic effect on SK-MEL-28 melanoma cells. 30 Finally, the water extracts of Solanum nigrum , a herb in traditional Chinese medicine, has cytotoxic effect against human melanoma cell lines and inhibited the metastasis of mouse melanoma cells. 31

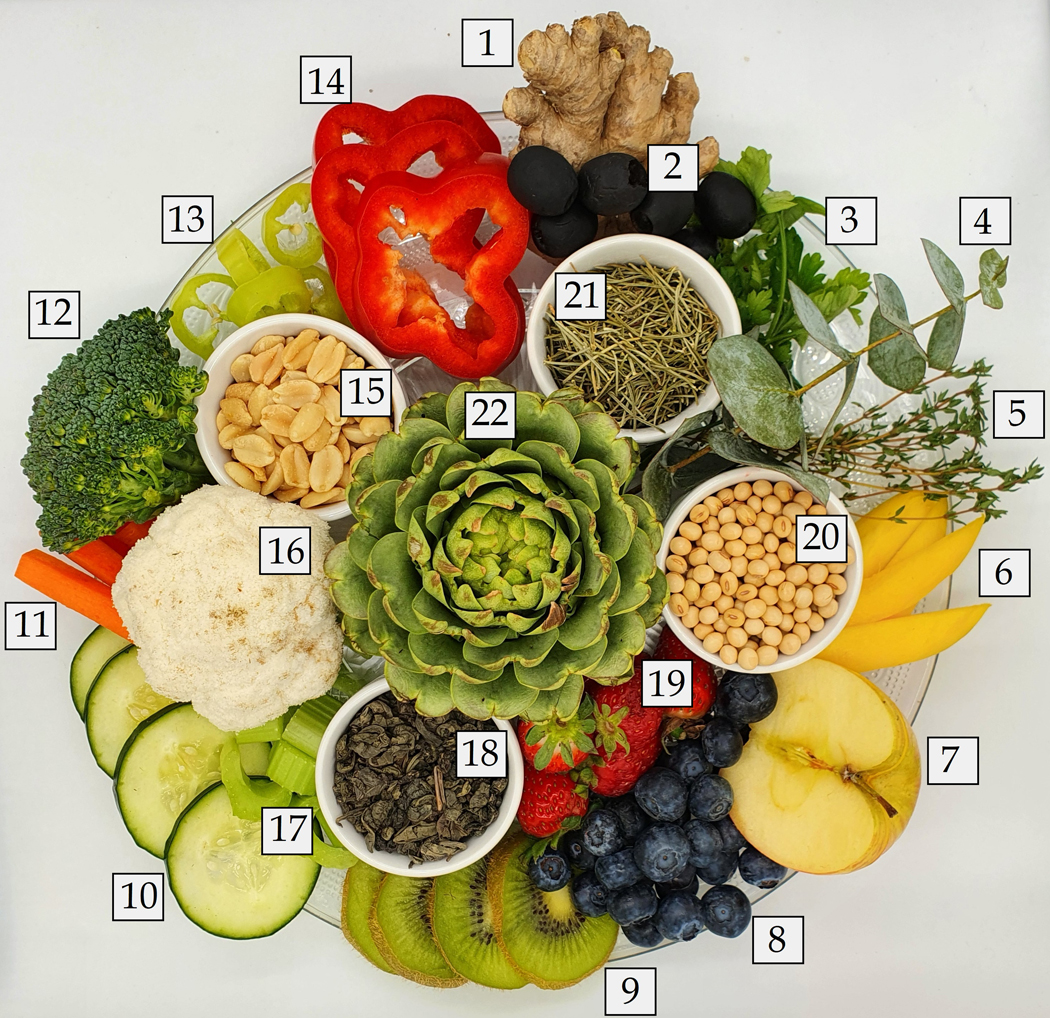

Phytochemicals with proven in vitro activity in melanoma models are: Capsaicin, found in chili peppers; 32 genistein, found in soybeans; 33 indole-3-carbinol, found in vegetables including broccoli, cauliflower, and brussels sprouts; 34 proanthocyanidins, found in cocoa, grapes, apple, tea and red wine; 35 resveratrol, found in grapes, peanuts, mulberries, cranberries, and eucalyptus; 14 fisetin, found in strawberries; mangoes, kiwis, apples, grapes, persimmons, cucumbers and onions; 36 luteolin found in carrots, peppers, celery, olives, peppermint, thyme, rosemary, and oregano; 37 apigenin, found in as parsley, celery, artichokes and chamomile; 13 betulinic acid, found in the birch bark; 38 quercetin, found in apples, berries, and onions; Berberine, found in roots of plants from the genus Berberis ; 39 Pancratistatin, obtained from the beach spider lily ( Hymencallis littoralis ); 39 Paradise tree extract, isolated from the Lakshmi Taru ( Simarouba glauca ); 39 and silymarin ( Silybum marianum ). 12 Some of the propolis compounds have shown biological activity, such as chrysin, which has been shown to stimulate IL-2 and IL-10 expression in murine melanoma cells, and galangin, which downregulates ERK 1/2 and activates p38 MAP kinases in human melanoma cells. Chitosan nanoparticles containing limonene and limonene-rich essential oils ( Citrus sinensis and Citrus limon ) showed viability reduction on melanoma cell line A375, but the mechanism is unknown. 40

Of note, some phytochemicals have shown potential benefit on metastatic disease. For instance, catechins (present in green tea extract) have been shown to modulate cancer cell growth, metastasis, angiogenesis, and other aspects of cancer progression by affecting different mechanisms. 41 Epidemiological studies suggest that regular consumption of green tea and ginseng attenuates the risk of many cancers. The main catechin with anticancer activity in green tea is epigallocatechin-3-gallate, with evidence showing promising effects in melanoma models. 41

Curcumin anti-neoplastic and anti-angiogenic effects have been reported widely. Multiple studies have used curcumin or its analogues, 42 because of its known potent anti-angiogenic, antiproliferative and proapoptotic effects in melanoma cells. 43 In contrast to NMSC, no human studies on melanoma patients have been reported to date.

How curcumin exerts its antitumoral effects in cutaneous melanoma is yet to be completely elucidated, but it involves anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative pathways which allow it to selectively target melanoma cells. 39 It has been described to interact with NF-kB, 44 caspases, miRNA, Bcl-2 protein expression, 44 inducible nitric oxide synthase inhibition, 45 downregulation of DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit; and upregulation of p53, p21, p27, checkpoint kinase 2. 45 Also by activation of mammalian sterile 20-like kinase 1, downregulation of phosphatase of regenerating liver-3 expression, lowering levels of STAT3 and JAK-2 protein phosphorylation, 44 pore opening of mitochondrial permeability transition with activation of cell death pathway, inhibition of matrixmetalloproteinase-2 activity, and downregulation of AKT/mTOR, among other effects. 43 Non-selective inhibition of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase 1–5 has also been described. 43 Curcuminoids have also shown anti-cancer activity, such as EF24, which inhibits the NF- kB; DM-1, modulating iNOS and COX-2 gene expression; and D6, inducing overexpression of heat shock proteins, among others. 42

Because of the limited oral bioavailability of curcumin, different mechanisms have been tested to improve delivery: micelles; transdermal presentations; chitosan-coated nanoparticles; among others. When cooked, curcumin decomposition products include deketene curcumin, with proven toxicity on melanoma cells. Visible light and combined red and blue light irradiation could synergize with curcumin enhancing apoptosis in human melanoma cells. 42 However, stimulation of natural killer cells with curcumin reduced the level of IL-12- induced IFN-γ secretion and production of granzyme-B or IFN-γ. 42 These latter immunologic effects imply that curcumin might also adversely affect the responsiveness of immune effector cells to clinically relevant cytokines that possess anti-tumor properties. When evaluating effects on metastatic disease, oral administration of curcumin alone or through chitosan-coated nanoparticles in melanoma-tumor-bearing mice, inhibits the lung metastasis of melanoma by as much as 80%, increasing survival by 144%. 42

Berberine is a natural isoquinolone alkaloid which can be extracted through the roots of plants from the genus Berberis . 39 It increases melanoma cell levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) which causes AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activation, altering the activity of several signaling pathways. 39 Signaling molecules such as ERK and p38 MAPK are downregulated preventing invasive effects on cancer cells. A reduction in COX-2, PGE2 and PGE2 receptors prevents cancer cell migration, decreasing metastatic potential for melanoma cells. 39 Berberine has been tested on the B16F10 melanoma cell lines through in vitro and in vivo tests in combination with doxorubicin. Berberine and doxorubicin combination caused tumor volume (85%) decrease and weight (78%) loss when compared to control mice. 39

Pancratistatin:

Pancratistatin is obtained from the beach spider lily (Hemanocallis littoralis). It is thought that targets mitochondrial vulnerabilities which are unique to cancer cells. It induces apoptosis in melanoma cells in vitro. 39 When combined with tamoxifen, it was more effective that either agent alone both in the A375 and G361 human melanoma cell lines. 39

Although endocannabinoid system apparently does not influence melanoma growth and progression, a study showed that cannabinoid type 1 receptor might serve as a tumor-promoting signal in human melanoma cells. 18 Moreover, activation of cannabinoid receptors in melanoma cells showed a decrease in angiogenesis, proliferation, and metastasis, by altering Akt protein and pRb phosphorylation. 17 Anandamide, 2- arachidonoylglycerol, and palmitoylethanolamide have proven anti-melanoma effects in murine models. Additionally, mice treated with Tetrahydrocannabinol have shown inhibition of tumor growth and decreased melanoma viability and proliferation. 17

“Black salve” ( Sanguinaria canadensis) has shown to induce melanoma-cells death through caspase signaling pathway and oxidative stress. We found 2 cases of melanoma treated with topical “black salve” by patient’s initiative. In both cases, the site of the application presented ulceration and evolved with local recurrence and metastatic disease. 20 Furthermore, eschars formed by this formulation can mimic melanoma and obscure clinical evaluation.

3. Vitamin C:

At millimolar concentrations vitamin C reduced cell viability, invasiveness, and induced apoptosis in vitro. At micromolar concentrations promoted cell growth, migration, and cell cycle progression, and protected against mitochondrial stress, with higher tumor volume in mice compared to control group. Furthermore, vitamin C displayed synergistic cytotoxicity with Vemurafenib. 46

Discussion:

In this article, we have reviewed the published data on CAM on skin cancers. It is undeniable that many patients look for and use CAM therapies, so clinicians must be informed regarding the different compounds ( Figure 1 ). The attitude and perception of CAM is improving among physicians, as show in an Italian study where 42% believed that CAM could have an integrative role. 47 It is important to highlight that many ‘conventional’ dermatologic treatments widely used nowadays, have derived from ‘natural’ compounds (e.g., tacrolimus, 8-methoxypsoralen, podophyllin, and salicylates, among others). 1 We believe that a comprehensive knowledge of the role of CAM ( Table 1 ) can strengthen the patient-physician relationship, potentially improving patient care. 1

Examples of herbs with compounds studied on skin cancer.

Figure 1A : celery (red arrow), grape seeds (green arrow), ground turmeric (curcuma, on orange arrow), and parsley (blue arrow). Photographs by Karina Carrasco and Leonel Hidalgo.

There are several CAM therapies used on patients with skin cancer, and while most studies are in an experimental phase and have never been formally tested in humans, some have proven biological plausibility with potential clinical utility in the future. Clinicians should keep in mind that patient satisfaction from CAM ranges from 20% to 86% and specifically ask their patients about concurrent or past CAM use. 48 Asking patients regarding CAM use is important given there are inherent risks associated to CAM usage, including (1) avoidance and/or delay of assessment of conventional treatments, (2) potential side effects as a direct result of the CAM itself or from the (3) interaction with concurrent or future conventional therapies. For instance, turmeric has been found to decrease CYP450 activity and to inhibit cyclophosphamide-induced apoptosis and tumor regression. For specific side effects and interactions with specific agents see weblinks in Table 1 . Of CAM users, 37% have found to be at risk of interaction with their conventional therapies; and for Chinese herbs, this can reach up to 88%. 49 This has special relevance when treating patients with comorbidities that use anticoagulants/antiplatelets or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, where the risk of interaction is as high as 50%. Other drugs that may harm in combination with CAM are statins and hypoglycemic drugs. 49 Particular consequences should be considered when treating metastatic disease with systemic drugs, where the risk of interaction is even greater. In patients with systemic melanoma who receive systemic therapy (including interferon, chemotherapy, BRAF-inhibitors, and ipilimumab) and concurrent CAM use, the risk of interaction was as high as 85%. 49 Clinicians should also consider that CAMs have the potential of severe medical side effects (e.g. Ginkgo leaf extract has been linked to intracerebral hemorrhage) and not overlook these compounds. Furthermore, use of alternative therapies instead of conventional therapies was associated with worse survival rates for cancer patients. 47

Even though there is growing evidence for a role of CAM in skin cancer, most therapies currently used by patients have no formal medical indications and bear possible severe complications. Physicians should educate themselves on CAMs to further educate their patients and lower the risk of interactions or the risk of omission of traditional, evidence-based therapies. We encourage clinicians to specifically ask patients for CAM use, to evaluate and avoid potential side effects. Despite emerging studies on animals, to date, there is no evidence from human clinical trials supporting the effectiveness of any CAM in the treatment of skin cancer, and future research must be done to elucidate their role in this field.

1. Ginger; 2. Olives; 3. Parsley; 4. Eucalyptus; 5. Thyme; 6. Mangoes; 7. Apple; 8. Blueberries (one of the many kinds of berries); 9. Kiwis; 10. Cucumbers; 11. Carrots; 12. Broccoli; 13. Chili peppers; 14. Pepper; 15. Peanuts; 16. Cauliflower; 17. Celery; 18. Green tea; 19. Strawberries; 20. Soybeans; 21. Rosemary; 22. Artichokes. Photographs by Karina Carrasco and Leonel Hidalgo.

Founding source:

This research is funded in part by grant from the National Cancer Institute / National Institutes of Health (P30-CA008748) made to the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Abbreviations used:

B-cell lymphoma 2

Extracelular signal regulated kinase 1 and 2

squamous cell carcinoma

Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen

matrixmetalloproteinase-2

matrixmetalloproteinase-9

Ataxia-telangiectasia-mutated

Ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related

breast cancer 1

Checkpoint kinase 1

Checkpoint kinase 2

Tumor necrosis factor receptor

nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

mammalian Target of Rapamycin

Cannabinod receptor type 1

Cannabinod receptor type 2

Non-melanoma skin cancer

B-cell lymphoma-extra large

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

Tyrosinase related protein 1

Tyrosinase related protein 2

Messenger RNA

Interleukin 8

Protein kinase C alpha

Nitric oxide

Interleukin 6

phosphatidylinositide 3-kinases

mitogen-activated protein kinase

c-Jun N-terminal kinases

Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor

Cyclin- dependent kinase 2

Cyclin- dependent kinase 4

thrombospondin-1

Activator protein 1

α-Melanocyte-stimulating hormone

reactive oxygen species

Interleukin 1 beta

Inducible nitric oxide synthase

Cyclooxygenase-2

matrixmetalloproteinases

Interleukin 12

Tumor necrosis factor alpha

Nuclear localization leucine-rich-repeat protein 1

Interleukin 2

Interleukin 10

DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit expression

Phosphatase of regenerating liver-3

Mammalian Sterile 20-like kinase 1

Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1

Interferon gamma

Mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening

Heat shock proteins

Cannabinoid receptoy type 1

Cannabinoid receptoy type 2

Palmitoylethanolamide

Tetrahydrocannabinol

Conflict of interest: The authors have not conflict of interest to declare.

Consent for publication: The authors consent the publication of this submission (manuscript and figures).

Prior presentation: none.

IRB status: N/A.

References:

- 1. Pourang A, Hendricks AJ, Shi VY. Managing dermatology patients who prefer “all natural” treatments. Clin Dermatol 2020;38:348–53. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Motoo Y, Yukawa K, Hisamura K, Tsutani K, Arai I. Internet survey on the provision of complementary and alternative medicine in Japanese private clinics: a cross-sectional study. J Integr Med 2019;17:8–13. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Loquai C, Dechent D, Garzarolli M, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine: A multicenter cross-sectional study in 1089 melanoma patients. Eur J Cancer 2017;71:70–9. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Dinehart SM, Alstadt K. Use of alternative therapies by patients undergoing surgery for nonmelanoma skin cancer. Dermatol Surg 2002;28:443–6. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Söllner W, Zingg-Schir M, Rumpold G, Fritsch P. Attitude toward alternative therapy, compliance with standard treatment, and need for emotional support in patients with melanoma. Arch Dermatol 1997;133:316–21. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Jellinek N, Maloney ME. Escharotic and other botanical agents for the treatment of skin cancer: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005;53:487–95. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Zhang YH, Peng HY, Xia GH, Wang MY, Han Y. Anticancer effect of two diterpenoid compounds isolated from Annona glabra Linn. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2004;25:937–42. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Takasaki M, Konoshima T, Murata Y, et al. Anticarcinogenic activity of natural sweeteners, cucurbitane glycosides, from Momordica grosvenori. Cancer Lett 2003;198:37–42. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Hostanska K, Daum G, Saller R. Cytostatic and apoptosis-inducing activity of boswellic acids toward malignant cell lines in vitro. Anticancer Res 2002;22:2853–62. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Khuda-Bukhsh AR, Bhattacharyya SS, Paul S, Boujedaini N. Polymeric nanoparticle encapsulation of a naturally occurring plant scopoletin and its effects on human melanoma cell A375. Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Xue Bao 2010;8:853–62. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Auriemma M, Di Nicola M, Gonzalez S, Piaserico S, Capo A, Amerio P. Polypodium leucotomos supplementation in the treatment of scalp actinic keratosis: could it improve the efficacy of photodynamic therapy? Dermatol Surg 2015;41:898–902. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Prasad RR, Paudel S, Raina K, Agarwal R. Silibinin and non-melanoma skin cancers. J Tradit Complement Med 2020;10:236–44. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Zhao G, Han X, Cheng W, et al. Apigenin inhibits proliferation and invasion, and induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in human melanoma cells. Oncol Rep 2017;37:2277–85. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Carletto B, Berton J, Ferreira TN, et al. Resveratrol-loaded nanocapsules inhibit murine melanoma tumor growth. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2016;144:65–72. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Almalki Z, Algregri M, Alhosin M, Alkhaled M, Damiati S, Zamzami MA. In vitro cytotoxicity of curcuminoids against head and neck cancer HNO97 cell line. Braz J Biol 2021;83:e248708. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Cheng AL, Hsu CH, Lin JK, et al. Phase I clinical trial of curcumin, a chemopreventive agent, in patients with high-risk or pre-malignant lesions. Anticancer Res 2001;21:2895–900. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Ladin DA, Soliman E, Griffin L, Van Dross R. Preclinical and Clinical Assessment of Cannabinoids as Anti-Cancer Agents. Front Pharmacol 2016;7:361. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Carpi S, Fogli S, Polini B, et al. Tumor-promoting effects of cannabinoid receptor type 1 in human melanoma cells. Toxicol In Vitro 2017;40:272–9. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Lim A Black salve treatment of skin cancer: a review. J Dermatolog Treat 2018;29:388–92. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Leecy TN, Beer TW, Harvey NT, et al. Histopathological features associated with application of black salve to cutaneous lesions: a series of 16 cases and review of the literature. Pathology 2013;45:670–4. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Lambert JD, Sang S, Dougherty A, et al. Cytotoxic lignans from Larrea tridentata. Phytochemistry 2005;66:811–5. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Lo CY, Liu PL, Lin LC, et al. Antimelanoma and antityrosinase from Alpinia galangal constituents. ScientificWorldJournal 2013;2013:186505. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Nakashima S, Oda Y, Nakamura S, et al. Inhibitors of melanogenesis in B16 melanoma 4A5 cells from flower buds of Lawsonia inermis (Henna). Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2015;25:2702–6. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Meng TX, Irino N, Kondo R. Melanin biosynthesis inhibitory activity of a compound isolated from young green barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) in B16 melanoma cells. J Nat Med 2015;69:427–31. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Nakashima S, Matsuda H, Oda Y, Nakamura S, Xu F, Yoshikawa M. Melanogenesis inhibitors from the desert plant Anastatica hierochuntica in B16 melanoma cells. Bioorg Med Chem 2010;18:2337–45. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Ghosh S, Bishayee K, Paul A, et al. Homeopathic mother tincture of Phytolacca decandra induces apoptosis in skin melanoma cells by activating caspase-mediated signaling via reactive oxygen species elevation. J Integr Med 2013;11:116–24. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Chakraborty D, Ghosh S, Bishayee K, Mukherjee A, Sikdar S, Khuda-Bukhsh AR. Antihyperglycemic drug Gymnema sylvestre also shows anticancer potentials in human melanoma A375 cells via reactive oxygen species generation and mitochondria-dependent caspase pathway. Integr Cancer Ther 2013;12:433–41. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Goldberg KH, Yin AC, Mupparapu A, Retzbach EP, Goldberg GS, Yang CF. Components in aqueous Hibiscus rosa-sinensis flower extract inhibit in vitro melanoma cell growth. J Tradit Complement Med 2017;7:45–9. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Barbieri A, Quagliariello V, Del Vecchio V, et al. Anticancer and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Ganoderma lucidum Extract Effects on Melanoma and Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Treatment. Nutrients 2017;9. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Valiahdi SM, Iranshahi M, Sahebkar A. Cytotoxic activities of phytochemicals from Ferula species. Daru 2013;21:39. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Ling B, Michel D, Sakharkar MK, Yang J. Evaluating the cytotoxic effects of the water extracts of four anticancer herbs against human malignant melanoma cells. Drug Des Devel Ther 2016;10:3563–72. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Shin DH, Kim OH, Jun HS, Kang MK. Inhibitory effect of capsaicin on B16-F10 melanoma cell migration via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt/Rac1 signal pathway. Exp Mol Med 2008;40:486–94. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Danciu C, Borcan F, Bojin F, Zupko I, Dehelean C. Effect of the isoflavone genistein on tumor size, metastasis potential and melanization in a B16 mouse model of murine melanoma. Nat Prod Commun 2013;8:343–6. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Aronchik I, Kundu A, Quirit JG, Firestone GL. The antiproliferative response of indole-3-carbinol in human melanoma cells is triggered by an interaction with NEDD4–1 and disruption of wild-type PTEN degradation. Mol Cancer Res 2014;12:1621–34. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Vaid M, Singh T, Prasad R, Katiyar SK. Bioactive proanthocyanidins inhibit growth and induce apoptosis in human melanoma cells by decreasing the accumulation of β-catenin. Int J Oncol 2016;48:624–34. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Pal HC, Baxter RD, Hunt KM, et al. Fisetin, a phytochemical, potentiates sorafenib-induced apoptosis and abrogates tumor growth in athymic nude mice implanted with BRAF-mutated melanoma cells. Oncotarget 2015;6:28296–311. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Kwak JY, Seok JK, Suh HJ, et al. Antimelanogenic effects of luteolin 7-sulfate isolated from Phyllospadix iwatensis Makino. Br J Dermatol 2016;175:501–11. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Ju EM, Lee SE, Hwang HJ, Kim JH. Antioxidant and anticancer activity of extract from Betula platyphylla var. japonica. Life Sci 2004;74:1013–26. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Sood S, Jayachandiran R, Pandey S. Current Advancements and Novel Strategies in the Treatment of Metastatic Melanoma. Integr Cancer Ther 2021;20:1534735421990078. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Alipanah H, Farjam M, Zarenezhad E, Roozitalab G, Osanloo M. Chitosan nanoparticles containing limonene and limonene-rich essential oils: potential phytotherapy agents for the treatment of melanoma and breast cancers. BMC Complement Med Ther 2021;21:186. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Zhang J, Lei Z, Huang Z, et al. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate(EGCG) suppresses melanoma cell growth and metastasis by targeting TRAF6 activity. Oncotarget 2016;7:79557–71. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Mirzaei H, Naseri G, Rezaee R, et al. Curcumin: A new candidate for melanoma therapy? Int J Cancer 2016;139:1683–95. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. Zhao G, Han X, Zheng S, et al. Curcumin induces autophagy, inhibits proliferation and invasion by downregulating AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in human melanoma cells. Oncol Rep 2016;35:1065–74. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. Zhang YP, Li YQ, Lv YT, Wang JM. Effect of curcumin on the proliferation, apoptosis, migration, and invasion of human melanoma A375 cells. Genet Mol Res 2015;14:1056–67. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. Zheng M, Ekmekcioglu S, Walch ET, Tang CH, Grimm EA. Inhibition of nuclear factor-kappaB and nitric oxide by curcumin induces G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human melanoma cells. Melanoma Res 2004;14:165–71. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 46. Yang G, Yan Y, Ma Y, Yang Y. Vitamin C at high concentrations induces cytotoxicity in malignant melanoma but promotes tumor growth at low concentrations. Mol Carcinog 2017;56:1965–76. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 47. Berretta M, Rinaldi L, Taibi R, et al. Physician Attitudes and Perceptions of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM): A Multicentre Italian Study. Front Oncol 2020;10:594. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 48. Vapiwala N, Mick R, Hampshire MK, Metz JM, DeNittis AS. Patient initiation of complementary and alternative medical therapies (CAM) following cancer diagnosis. Cancer J 2006;12:467–74. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 49. Loquai C, Schmidtmann I, Garzarolli M, et al. Interactions from complementary and alternative medicine in patients with melanoma. Melanoma Res 2017;27:238–42. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 50. Lopez G, Mao JJ, Cohen L. Integrative Oncology. Med Clin North Am 2017;101:977–85. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (983.1 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections