Root out friction in every digital experience, super-charge conversion rates, and optimize digital self-service

Uncover insights from any interaction, deliver AI-powered agent coaching, and reduce cost to serve

Increase revenue and loyalty with real-time insights and recommendations delivered to teams on the ground

Know how your people feel and empower managers to improve employee engagement, productivity, and retention

Take action in the moments that matter most along the employee journey and drive bottom line growth

Whatever they’re saying, wherever they’re saying it, know exactly what’s going on with your people

Get faster, richer insights with qual and quant tools that make powerful market research available to everyone

Run concept tests, pricing studies, prototyping + more with fast, powerful studies designed by UX research experts

Track your brand performance 24/7 and act quickly to respond to opportunities and challenges in your market

Explore the platform powering Experience Management

- Free Account

- Product Demos

- For Digital

- For Customer Care

- For Human Resources

- For Researchers

- Financial Services

- All Industries

Popular Use Cases

- Customer Experience

- Employee Experience

- Net Promoter Score

- Voice of Customer

- Customer Success Hub

- Product Documentation

- Training & Certification

- XM Institute

- Popular Resources

- Customer Stories

- Artificial Intelligence

Market Research

- Partnerships

- Marketplace

The annual gathering of the experience leaders at the world’s iconic brands building breakthrough business results, live in Salt Lake City.

- English/AU & NZ

- Español/Europa

- Español/América Latina

- Português Brasileiro

- REQUEST DEMO

- Experience Management

- Business Research

Try Qualtrics for free

Business research: definition, types & methods.

10 min read What is business research and why does it matter? Here are some of the ways business research can be helpful to your company, whichever method you choose to carry it out.

What is business research?

Business research helps companies make better business decisions by gathering information. The scope of the term business research is quite broad – it acts as an umbrella that covers every aspect of business, from finances to advertising creative. It can include research methods which help a company better understand its target market. It could focus on customer experience and assess customer satisfaction levels. Or it could involve sizing up the competition through competitor research.

Often when carrying out business research, companies are looking at their own data, sourced from their employees, their customers and their business records. However, business researchers can go beyond their own company in order to collect relevant information and understand patterns that may help leaders make informed decisions. For example, a business may carry out ethnographic research where the participants are studied in the context of their everyday lives, rather than just in their role as consumer, or look at secondary data sources such as open access public records and empirical research carried out in academic studies.

There is also a body of knowledge about business in general that can be mined for business research purposes. For example organizational theory and general studies on consumer behavior.

Free eBook: This Year’s Global Market Research Trends Report

Why is business research important?

We live in a time of high speed technological progress and hyper-connectedness. Customers have an entire market at their fingertips and can easily switch brands if a competitor is offering something better than you are. At the same time, the world of business has evolved to the point of near-saturation. It’s hard to think of a need that hasn’t been addressed by someone’s innovative product or service.

The combination of ease of switching, high consumer awareness and a super-evolved marketplace crowded with companies and their offerings means that businesses must do whatever they can to find and maintain an edge. Business research is one of the most useful weapons in the fight against business obscurity, since it allows companies to gain a deep understanding of buyer behavior and stay up to date at all times with detailed information on their market.

Thanks to the standard of modern business research tools and methods, it’s now possible for business analysts to track the intricate relationships between competitors, financial markets, social trends, geopolitical changes, world events, and more.

Find out how to conduct your own market research and make use of existing market research data with our Ultimate guide to market research

Types of business research

Business research methods vary widely, but they can be grouped into two broad categories – qualitative research and quantitative research .

Qualitative research methods

Qualitative business research deals with non-numerical data such as people’s thoughts, feelings and opinions. It relies heavily on the observations of researchers, who collect data from a relatively small number of participants – often through direct interactions.

Qualitative research interviews take place one-on-one between a researcher and participant. In a business context, the participant might be a customer, a supplier, an employee or other stakeholder. Using open-ended questions , the researcher conducts the interview in either a structured or unstructured format. Structured interviews stick closely to a question list and scripted phrases, while unstructured interviews are more conversational and exploratory. As well as listening to the participant’s responses, the interviewer will observe non-verbal information such as posture, tone of voice and facial expression.

Focus groups

Like the qualitative interview, a focus group is a form of business research that uses direct interaction between the researcher and participants to collect data. In focus groups , a small number of participants (usually around 10) take part in a group discussion led by a researcher who acts as moderator. The researcher asks questions and takes note of the responses, as in a qualitative research interview. Sampling for focus groups is usually purposive rather than random, so that the group members represent varied points of view.

Observational studies

In an observational study, the researcher may not directly interact with participants at all, but will pay attention to practical situations, such as a busy sales floor full of potential customers, or a conference for some relevant business activity. They will hear people speak and watch their interactions , then record relevant data such as behavior patterns that relate to the subject they are interested in. Observational studies can be classified as a type of ethnographic research. They can be used to gain insight about a company’s target audience in their everyday lives, or study employee behaviors in actual business situations.

Ethnographic Research

Ethnographic research is an immersive design of research where one observes peoples’ behavior in their natural environment. Ethnography was most commonly found in the anthropology field and is now practices across a wide range of social sciences.

Ehnography is used to support a designer’s deeper understanding of the design problem – including the relevant domain, audience(s), processes, goals and context(s) of use.

The ethnographic research process is a popular methodology used in the software development lifecycle. It helps create better UI/UX flow based on the real needs of the end-users.

If you truly want to understand your customers’ needs, wants, desires, pain-points “walking a mile” in their shoes enables this. Ethnographic research is this deeply rooted part of research where you truly learn your targe audiences’ problem to craft the perfect solution.

Case study research

A case study is a detailed piece of research that provides in depth knowledge about a specific person, place or organization. In the context of business research, case study research might focus on organizational dynamics or company culture in an actual business setting, and case studies have been used to develop new theories about how businesses operate. Proponents of case study research feel that it adds significant value in making theoretical and empirical advances. However its detractors point out that it can be time consuming and expensive, requiring highly skilled researchers to carry it out.

Quantitative research methods

Quantitative research focuses on countable data that is objective in nature. It relies on finding the patterns and relationships that emerge from mass data – for example by analyzing the material posted on social media platforms, or via surveys of the target audience. Data collected through quantitative methods is empirical in nature and can be analyzed using statistical techniques. Unlike qualitative approaches, a quantitative research method is usually reliant on finding the right sample size, as this will determine whether the results are representative. These are just a few methods – there are many more.

Surveys are one of the most effective ways to conduct business research. They use a highly structured questionnaire which is distributed to participants, typically online (although in the past, face to face and telephone surveys were widely used). The questions are predominantly closed-ended, limiting the range of responses so that they can be grouped and analyzed at scale using statistical tools. However surveys can also be used to get a better understanding of the pain points customers face by providing open field responses where they can express themselves in their own words. Both types of data can be captured on the same questionnaire, which offers efficiency of time and cost to the researcher.

Correlational research

Correlational research looks at the relationship between two entities, neither of which are manipulated by the researcher. For example, this might be the in-store sales of a certain product line and the proportion of female customers subscribed to a mailing list. Using statistical analysis methods, researchers can determine the strength of the correlation and even discover intricate relationships between the two variables. Compared with simple observation and intuition, correlation may identify further information about business activity and its impact, pointing the way towards potential improvements and more revenue.

Experimental research

It may sound like something that is strictly for scientists, but experimental research is used by both businesses and scholars alike. When conducted as part of the business intelligence process, experimental research is used to test different tactics to see which ones are most successful – for example one marketing approach versus another. In the simplest form of experimental research, the researcher identifies a dependent variable and an independent variable. The hypothesis is that the independent variable has no effect on the dependent variable, and the researcher will change the independent one to test this assumption. In a business context, the hypothesis might be that price has no relationship to customer satisfaction. The researcher manipulates the price and observes the C-Sat scores to see if there’s an effect.

The best tools for business research

You can make the business research process much quicker and more efficient by selecting the right tools. Business research methods like surveys and interviews demand tools and technologies that can store vast quantities of data while making them easy to access and navigate. If your system can also carry out statistical analysis, and provide predictive recommendations to help you with your business decisions, so much the better.

Free eBook: This Year's Global Market Research Trends Report

Related resources

Descriptive research 8 min read, mixed methods research 17 min read, market intelligence 10 min read, marketing insights 11 min read, ethnographic research 11 min read, qualitative vs quantitative research 13 min read, primary vs secondary research 14 min read, request demo.

Ready to learn more about Qualtrics?

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Business Education

- Business Law

- Business Policy and Strategy

- Entrepreneurship

- Human Resource Management

- Information Systems

- International Business

- Negotiations and Bargaining

- Operations Management

- Organization Theory

- Organizational Behavior

- Problem Solving and Creativity

- Research Methods

- Social Issues

- Technology and Innovation Management

- Share Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Business research process.

- James A. Muncy James A. Muncy Marketing, Bradley University

- , and Alice M. Muncy Alice M. Muncy Accounting, Baylor University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190224851.013.215

- Published online: 27 October 2020

Business research is conducted by both businesspeople, who have informational needs, and scholars, whose field of study is business. Though some of the specifics as to how research is conducted differs between scholarly research and applied research, the general process they follow is the same. Business research is conducted in five stages. The first stage is problem formation where the objectives of the research are established. The second stage is research design . In this stage, the researcher identifies the variables of interest and possible relationships among those variables, decides on the appropriate data source and measurement approach, and plans the sampling methodology. It is also within the research design stage that the role that time will play in the study is determined. The third stage is data collection . Researchers must decide whether to outsource the data collection process or collect the data themselves. Also, data quality issues must be addressed in the collection of the data. The fourth stage is data analysis . The data must be prepared and cleaned. Statistical packages or programs such as SAS, SPSS, STATA, and R are used to analyze quantitative data. In the cases of qualitative data, coding, artificial intelligence, and/or interpretive analysis is employed. The fifth stage is the presentation of results . In applied business research, the results are typically limited in their distribution and they must be addressed to the immediate problem at hand. In scholarly business research, the results are intended to be widely distributed through journals, books, and conferences. As a means of quality control, scholarly research usually goes through a double-blind review process before it is published.

- business research

- research design

- scholarly research

- applied research

- data collection

- data analysis

- data quality

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Business and Management. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 07 November 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|195.158.225.230]

- 195.158.225.230

Character limit 500 /500

A Roadmap to Business Research

- First Online: 15 March 2023

Cite this chapter

- Merwe Oberholzer ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7180-8865 3 &

- Pieter W. Buys ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5345-3594 3

719 Accesses

This chapter seeks to constitute a roadmap or framework to guide business researchers in contextualizing and planning their research efforts. A literature study was conducted to investigate the research concept, the boundary of research, and the research process’ conceptual framework. This chapter summarized research as a systematic investigation to reveal new knowledge. In guiding industry-orientated business research, it is acknowledged that management action may solve some business problems. In contrast, higher levels of organizational issues and critical reflection of business issues may require actual research .

The framework for business research is divided into four parts: the research problem, research design, empirical evidence, and conclusion. The central part of the map is the design section that organizes the philosophic approach (theoretical foundation, research philosophy, and assumptions) on the one side and the applied research methods and techniques on the other side, with the research methodology acting as a bridge between the sides. The framework constitutes a guide when embarking on the journey to solve industry-orientated business research.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Business Research Process

What is the Metaverse? Challenges, Opportunities, Definition, and Future Research Directions

Basic Research Methods

AS illustrated later, it must be noted not every business problem needs to be solved by scientific research.

Note that although conceptually four distinct elements, in actuality these ProDEC elements are highly integrated.

Note that the theoretical foundation may not be of equal importance in all paradigms, e.g., the pragmatist and design sciences paradigms where a pragmatic problem solution or artifact is the primary objective.

Abutabenjeh, S., & Jaradat, R. (2018). Clarification of research design, research methods, and research methodology: A guide for public administration researchers and practitioners. Teaching Public Administration, 36 (3), 237–258.

Article Google Scholar

Babbie, E. (2004). The practice of social research . Thomson/ Wadsworth.

Google Scholar

Brierley, J. A. (2017). The role of a pragmatist paradigm when adopting mixed methods in behavioural accounting research. International Journal of Behavioural Accounting and Finance, 6 (2), 140–154.

Collins. (2021). Definition of research . https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/research Date of access: 21 July 2021.

Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed method research . Sage.

Davis, C., & Fisher, M. (2018). Understanding Research Paradigms. JARNA, 21 (3), 21–25.

Delen, D., & Zolbanin, H. M. (2018). The analytics paradigm in business research. Journal of Business Research, 90 , 186–195.

Department of Education and Training, Western Sydney University. 2020. Research services. https://www.westernsydney.edu.au/research/researchers/preparing_a_grant_application/dest_definition_of_research . Date of access: 21 July 2021.

Elsayed, N., & Elbardan, H. (2018). Investigating the associations between executive compensation and firm performance: Agency theory or tournament theory. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 19 (2), 245–270.

FindAPhD.com. (2021). What are the criteria for a PhD? https://www.findaphd.com/advice/finding/criteria-for-phd.aspx Date of access: 18 August 2021.

Goldkuhl, G. (2011). Design research in search for a paradigm: Pragmatism is the answer. European Design Science Symposium (pp. 84–95). Springer.

Goldkuhl, G. (2020). Design Science Epistemology: A pragmatist inquiry. Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems, 32 (1), 39–79.

Hesse-Biber, S. N., & Leavy, P. (2011). The practice of qualitative research . Sage.

Henderson, K. A. (2011). Post-positivism and the pragmatics of leisure research. Leisure Sciences, 33 (4), 341–346.

Hevner, A.R., March, S.T., Park, J. & Ram, S. (2004). Design science in information systems research. MIS quarterly : 75–105.

Kessler, E. H. (Ed.). (2013). Encyclopedia of management theory . Sage.

Kankam, P. K. (2019). The use of paradigms in information research. Library & Information Science Research, 41 (2), 85–92.

Kekeya, J. (2019, November). The commonalities and differences between research paradigms. Contemporary PNG Studies: DWU Research Journal, 31 , 26–36.

Kivunja, C. (2018). Distinguishing between theory, theoretical framework, and conceptual framework: A systematic review of lessons from the field. International Journal of Higher Education, 7 (6), 44–53.

Kivunja, C., & Kuyini, A. B. (2017). Understanding and applying research paradigms in educational contexts. International Journal for Higher Education, 6 (5), 26–41.

Jansen, J. D. (2020a). What is a research question and why is it important? In: Maree, K., (ed.), First steps in research . Van Schaik. pp. 2–14.

Jansen, J. D. (2020b). Introduction to the language of research. In: Maree, K., (ed.), First steps in research . Van Schaik. pp. 16–24.

Lexico.com. (2021). Oxford English and Spanish dictionary, synonyms, and Spanish to English translator . https://www.lexico.com/definition/research Date of access: 22 July 2021.

Lincoln, Y. S., Lynham, S. A., & Guba, E. G. (2011). Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences, revisited. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 97–128). Sage.

Myers, M. D. (2020). Qualitative research in business & management . Sage.

Mouton, J. (1996). Understanding social research . Van Schaik.

Mouton, J. (2011). How to succeed in your master’s & doctoral studies: A South African guide and resource book. Van Schaik.

Nieuwenhuis, J. (2020). Introducing qualitative research. In: Maree, K., (ed.), First steps in research . Van Schaik. pp. 56–76.

Pandey, P. & Pandey, M. M. (2015). Research methodology: Tools and techniques . Bridge Center: Buzau.

Pietersen, J. & Maree, K. (2020). Statistical analysis II: Inferential statistics. In: Maree, K., (ed.), First steps in research . Van Schaik. pp. 242–258.

Rahi, S. (2017). Research design and methods: A systematic review of research paradigms, sampling issues and instrument development. International Journal of Economics & Management Sciences, 6 (2), 1000403.

Rehman, A. A., & Alharthi, K. (2016). An introduction to research paradigms. International Journal of Educational Investigations, 3 (8), 51–59.

Saunders, M. N. K., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2019). Research methods for business students . Pearson.

Sein, M. K., Henfridsson, O., Purao, S., Rossi, M., & Lindgren, R. (2011). Action Design Research. MIS Quarterly, 35 (1), 37–56.

Tubey, R. J., Rotich, J. K., & Bengat, J. K. (2015). Research paradigms: Theory and practice. Research on Humanities and Social Sciences, 5 (5), 224–228.

Vom Brocke J., Hevner A., Maedche A. (2020). Introduction to Design Science Research. In: Vom Brocke J., Hevner A., Maedche A. (eds.), Design Science Research. Cases. Progress in IS. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-46781-4_1 Date of access: 21 October 2021.

Voxco. (2022). Business research: Definition, types, and methods. https://www.voxco.com/blog/business-research-definition-types-and-methods/ Date of access: 23 May 2022.

Wilson, J. (2013). Essentials of business research: A guide to doing your research project. Sage. https://www.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/upm-binaries/59838_Wilson_ch1.pdf Date of access: 3 June 2021.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Management Cybernetics Research Entity, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa

Merwe Oberholzer & Pieter W. Buys

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Pieter W. Buys .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Pieter W. Buys

Merwe Oberholzer

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Oberholzer, M., Buys, P.W. (2023). A Roadmap to Business Research. In: Buys, P.W., Oberholzer, M. (eds) Business Research . Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-9479-1_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-9479-1_2

Published : 15 March 2023

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-19-9478-4

Online ISBN : 978-981-19-9479-1

eBook Packages : Business and Management Business and Management (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

No internet connection.

All search filters on the page have been cleared., your search has been saved..

- Sign in to my profile My Profile

How to Understand the Language of Business Research Methods

- By: Melissa Mesek Edited by: Sonya Campbell-Perry

- Product: Sage Research Methods: Business

- Publisher: SAGE Publications Ltd

- Publication year: 2023

- Online pub date: March 21, 2023

- Discipline: Business and Management

- Methods: Case study research , Data collection , Quantitative data collection

- DOI: https:// doi. org/10.4135/9781529668476

- Keywords: knowledge , language , philosophy , publications Show all Show less

- Academic Level: Advanced Undergraduate Online ISBN: 9781529668476 More information Less information

This how-to guide identifies the key concepts behind the terminology that is used within business research methods and considers the importance of these key concepts to the overall research. It also outlines one qualitative and one quantitative research example to increase the understanding of these concepts for practical application. Moreover, search engines and library interfaces’ search possibilities are discussed to build on the reader’s research skills to find contemporary and relevant sources to understand the concepts highlighted in more depth. The third section reviews the ethical implications of doing research, which helps to understand the importance of the link between the individual researcher, the key concepts and the terminology utilised. This how-to guide finishes with some tips for problem-solving to become an independent researcher and recaps on the two strands of methodological inquiry with a graphical illustration.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this guide, readers should be able to:

- Identify the key concepts behind the language used to generate research methods, and their importance to the overall process of research.

- Use appropriate research skills to find useful and relevant sources to explore and increase understanding of these concepts.

- Understand the importance of the personal link between the language, the key concepts and the researcher.

- Increase theirability to identify the practical applications that sit behind the language in order to develop problem-solving skills.

Introduction

This how-to guide is meant to help you understand the terminology used in research methods better and consequently serve as an entry point for you to be diving into the key concepts, which sit behind this language. This guide also discusses good practice of researching to find core textbooks, journals, and other media sources to deepen your knowledge on research methods on your own. We also review practical applications of these concepts and hope to increase your skills to identify methods and then apply those in your own project. It is crucial to note that in this how-to guide, dichotomies are used in order to make the logical progressions that traditionally take place easier to understand; however, there can certainly be an overlap between the choices from both strands in some research methodologies ( Wilson, 2014 ). There is an ever-ranging debate between these two dichotomies (e.g., Beck, 1949 ), which concerns itself with the question whether the natural sciences, and consequently, the objective measuring with large data sets, is superior to social sciences that favours complex, in-depth and small data sets, often comprised of the written or spoken word instead of numericals.

This how-to guide starts with an introduction to the key concepts that sit behind the terminology in business methods research and utilises Saunders et al. (2019) 's Research Onion as a guiding tool. In the second part of this how-to guide, search engines and library interfaces’ search possibilities are discussed to show you how to find contemporary and relevant publications for your own research. In the third section, we review ethical considerations and the importance of the link between yourself as the researcher, the concepts and the terminology utilised. In the last section, we discuss the soft skills that are vital in order to learn more about business research methods and reveal some strategies on how to find more information on research methods beyond this how-to guide. Finally, there are some graphs on the strands of inquiry to help you understand the logical progression that takes place within research methods.

An Introduction to the Key Concepts in Business Research Methods

It is important that you grasp the key concepts in research methods behind the language used so that you can utilise this terminology effectively in your own research project. Having to make sense of these complex concepts behind the language can easily create a barrier for diving into research methods and can consequently make it harder to find the entry point for decoding and effectively using the terminology in your own research. At the beginning, it can likely feel like research methods are made up of jargon. However, this jargon is a very efficient way of explaining complex concepts in one term. Moreover, your research methods chapter informs your data collection tools, the robustness, reliability and novelty of your findings and your consequent analysis. All of these factors have a direct impact on the outcome of your research methods and analysis chapter, which form a significant part of your research project. This is why understanding the key concepts in research methods that sit behind the language that is used is vital for your research project’s success. In the following paragraphs, we will dissect the key concepts behind the language, which is meant to help you to start exploring the key concepts in more depth and to being able to utilise the terminology in your own research.

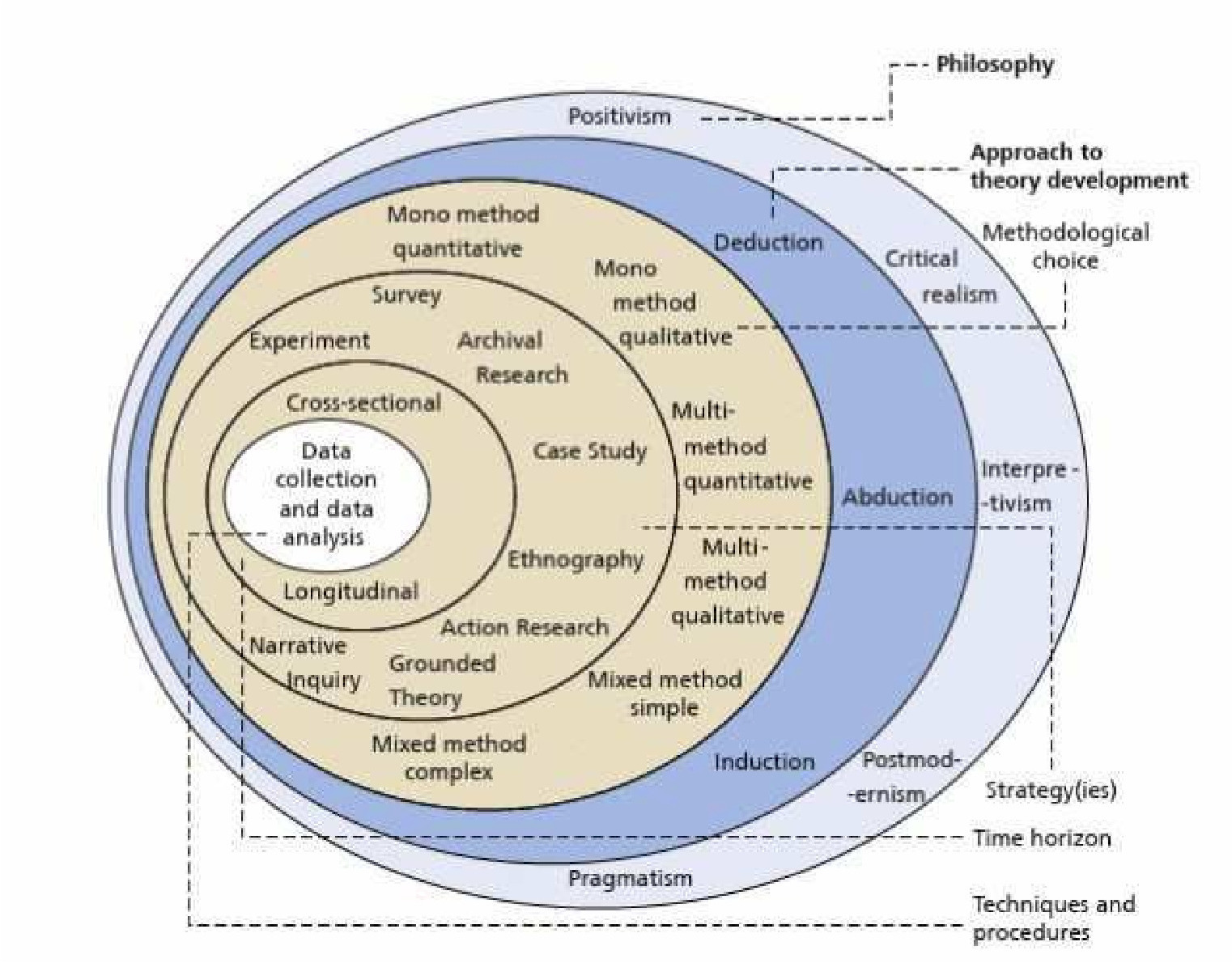

A framework that is widely used within the research community in order to depict the complexity of research methods is the Research Onion by Saunders et al. (2019) see Figure 1 . In this framework, the most important concepts are listed within layers and are meant to be explored one after the other, like peeling away layers from an onion.

The illustration houses six oval structures. The details depicted are as follows. From inside out, in clockwise directions the various components labeled within the oval structures reads as follows. The first oval structure at the center reads data collection and data analysis. A dotted arrow from data collection and data analysis is indicated toward techniques and procedures. The second oval structure reads cross-sectional and longitudinal. A dotted arrow from the second oval structure is indicated toward time horizon. The third oval structure reads experiment, survey, archival research, case study, ethnography, action research, grounded theory, inquiry, and narrative. A dotted arrow from the third oval structure is indicted toward strategy(ies). The fourth oval structure reads mono method quantitative, mono-method qualitative, multi-method quantitative, multi-method qualitative, mixed-method simple, and mixed-method complex. A dotted arrow from the fourth oval structure is indicated toward methodological choice. The fifth oval structure reads deduction, abduction, and induction respectively. A dotted arrow from the fifth oval structure is indicated toward approach to theory development. The sixth oval structure reads positivism, critical realism, interpretivism, postmodernism, and pragmatism. A dotted arrow from the sixth oval structure is indicated toward philosophy. The second, third and fourth oval structures from inside out and shaded in the same color.

Figure 1. Saunders et al. (2019)`s Research Onion

Source : Saunders et al., 2019

Philosophies is the first layer of the onion in the Saunders Onion ( Saunders et al., 2019 ). Philosophies serves as an umbrella term for two distinct concepts: the first is the Philosophy and the second is the Philosophical Prism . The Philosophy of your research determines what constitutes knowledge with three major ones to pick from: Epistemology, Axiology and Ontology ( Wilson, 2014 ). It is important to spend time with these concepts, as the choices made here have a direct impact on your consequent research design, e.g., methods and approaches. The first type, Epistemology, is a branch of philosophy that concerns itself with the nature of knowledge ( Alharahsheh & Pius, 2020 ; Antwi & Hamza, 2015 ). As part of this strand of philosophy, you can ask yourself questions such as ‘What constitutes knowledge?’ and ‘How do we know what we know?’ ( Antwi & Hamza, 2015, p. 219 ).

On the other hand, Ontology refers to our reality, the way individuals perceive the social world ( Wilson, 2014 ). The term ‘Ontology’ involves a branch of philosophy that focuses on the nature of the knowable or reality ( Wand & Weber, 1993 ; cited in Antwi & Hamza, 2015 ). This philosophy determines the structure and essence of reality and what we understand about reality ( Alharahsheh & Pius, 2020 ; Antwi & Hamza, 2015 ). And lastly, Axiology is rooted in the nature of value, with ethical problems as well as our own perceptions forming a notable part of this strand of philosophy( Alharahsheh & Pius, 2020 ; Antwi & Hamza, 2015 ).

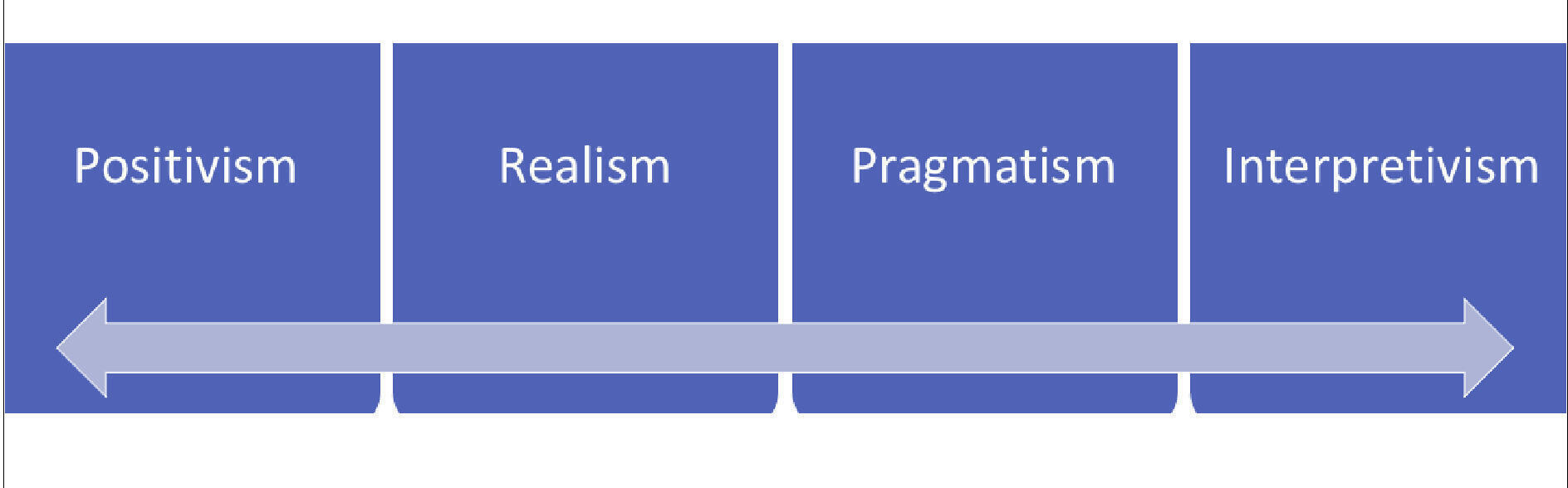

The second part of Philosophies within Saunders et al. (2019) is the Philosophical Prisms ( see Figure 2 ). This is the angle from or the lens through which you look at your research. There are a number of these possible lenses, and we would like to encourage you to do your own research after having read about the most used ones below. Positivism and Interpretivism sit on the opposite ends on the prism scale. In between, we can find Pragmatism and Realism. You would be utilising a positivist approach if you believe that there are no personal biases that can play a part in your research and that your research is fully objective ( Wilson, 2014 ). Positivists further believe that research must be fully scientific, which usually favours Ontology as a philosophy. Interpretivism is the right prism if your research question concerns itself with the complexities of the social aspects within the business environment that cannot be measured in the same way as the natural sciences ( Wilson, 2014 ). This research is often paired with Epistemology as a philosophy because it considers different types of knowledge and how knowledge is created particularly in our social settings ( Alharahsheh & Pius, 2020 ; Wilson, 2014 ). If none of these two angles suit your research question, you might fall more into the middle where we can find Pragmatism and Realism ( Alharahsheh & Pius, 2020 ; Antwi & Hamza, 2015 ). Pragmatism combines both social and physical world while focusing on questions surrounding the ‘how’ or the ‘what’ (cited in Creswell & Creswell, 2003 ; Wilson, 2014 ). This philosophical prism is most often chosen when the researcher utilises mixed methods, both quantitative and qualitative data collection tools (cited in Greene, 2007 ; Wilson, 2014 ). Realism (including critical realism) concerns itself with the reality that we understand through our senses as actors within this reality ( Scott, 2005 ).

The prism scale comprises series four square boxes. A bidirectional is spread across the four boxes. From left to right the boxes are labeled as follows.

Positivism, realism, pragmatism, interpretivism respectively.

Figure 2. Scale of Philosophical Prisms

Source : Created by Author (2022).

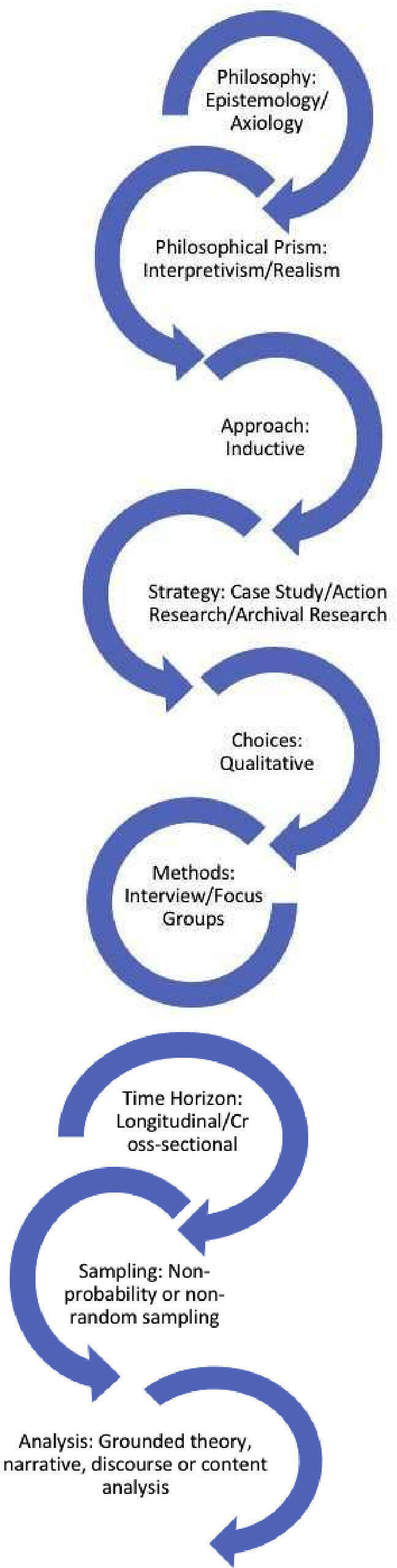

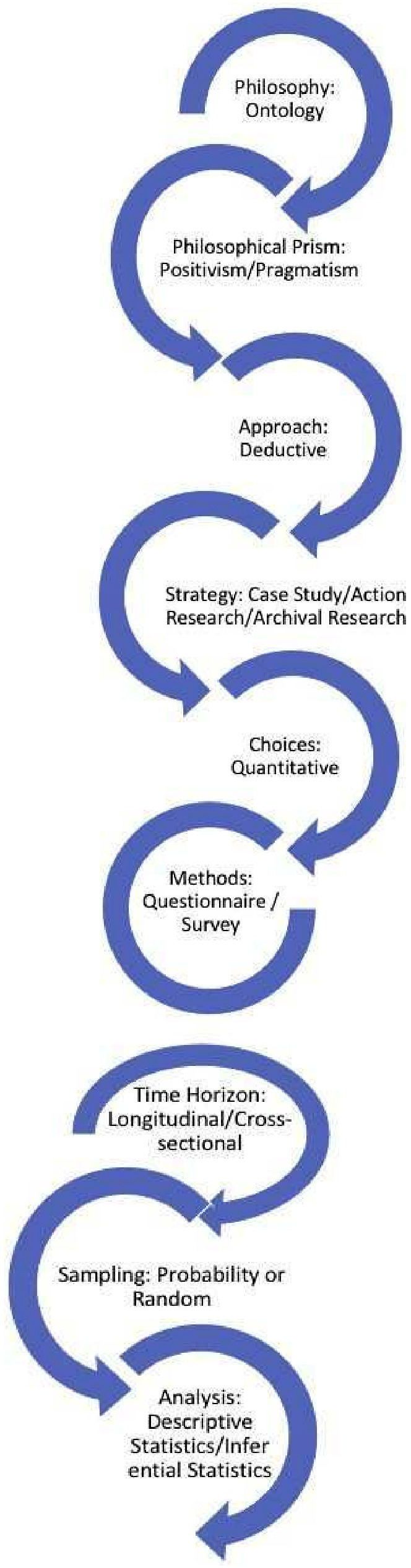

The second layer in the onion is Approaches ; two of these exist: deductive and inductive. Deductive is a theory-testing approach, whereas inductive is characterised by its theory-building capacity ( Wilson, 2014 ). By doing so, deductive utilises theory to test assumptions grounded in already existing literature ( Wilson, 2014 ). On the other end of the spectrum lies inductive that starts at the data collection to produce insights from which theory is built ( Wilson, 2014 ). As there are logical progressions within the methodology chapter, it is crucial to note that the approach taken has a direct influence on the next two layers, Strategies and Choices . For a high-level overview, please see Figure 4 and Figure 5 below.

The illustration two vertical rows of intertwined semi-cyclic arrow connecting the different components. The framework depicted on the left side reads as follows. A semi-cyclic arrow labeled philosophy: epistemology / axiology is indicated toward philosophical prism: interpretivism / realism which in turn is indicated toward approach: inductive. A semi-cyclic arrow from strategy: case study / action research / archival research is indicated toward choices: qualitative which in turn is indicated toward methods: interview / focus groups. A semi-cyclic arrow labeled time horizon: longitudinal / cross-sectional is indicated toward sampling: Non-probability or non-random sampling which in turn is indicated toward analysis: grounded theory, narrative, discourse or content analysis.

The framework depicted on the right side reads as follows. A semi-cyclic arrow labeled philosophy: ontology is indicated toward philosophical prism: positivism/ pragmatism which in turn is indicated toward approach: deductive. A semi-cyclic arrow from strategy: case study / action research / archival research is indicated toward choices: quantitative which in turn is indicated toward methods: questionnaire / survey. A semi-cyclic arrow labeled time horizon: longitudinal / cross-sectional is indicated toward sampling: Probability or random which in turn is indicated toward analysis: descriptive, statistics / inferential statistics.

Figure 4. Two strands of methodological inquiry

Source : Created by Author (2022)

The illustration two vertical rows of intertwined semi-cyclic arrow connecting the different components. The framework depicted on the left side reads as follows. A semi-cyclic arrow labeled philosophy: epistemology / axiology is indicated toward philosophical prism: interpretivism / realism which in turn is indicated toward approach: inductive. A semi-cyclic arrow from strategy: case study / action research / archival research is indicated toward choices: qualitative which in turn is indicated toward methods: interview / focus groups. A semi-cyclic arrow labeled time horizon: longitudinal / cross-sectional is indicated toward sampling: Non-probability or non-random sampling which in turn is indicated toward analysis: grounded theory, narrative, discourse or content analysis. The framework depicted on the right side reads as follows. A semi-cyclic arrow labeled philosophy: ontology is indicated toward philosophical prism: positivism/ pragmatism which in turn is indicated toward approach: deductive. A semi-cyclic arrow from strategy: case study / action research / archival research is indicated toward choices: quantitative which in turn is indicated toward methods: questionnaire / survey. A semi-cyclic arrow labeled time horizon: longitudinal / cross-sectional is indicated toward sampling: Probability or random which in turn is indicated toward analysis: descriptive, statistics / inferential statistics

Figure 5. Two strands of methodological inquiry

Within Strategies, you can choose from a pool of data collection tools, which are used for either qualitative data or for quantitative data collection. As part of the Strategies , you would also ask yourself whether you would like to use a case study approach or undertake archival research amongst other possibilities (for more information see Saunders et al., 2019 ). Once this strategy is chosen, you can go further to Choices . The Choices that you make are synonymous to the research methods used: mono-method, multi-method or mixed method. Deciding for a mono-method choice, you will use one data collection tool from either the qualitative or quantitative methods. For example, a questionnaire is a quantitative data collection tool, whereas an interview or a focus group is qualitative data collection tool. If you wanted to use more than one method, it is likely that you will either choose a multi-method, utilising multiple data collection tools within either qualitative or quantitative methods or a mixed-method approach, as part of which you would want to use a mix of both qualitative and quantitative data collection tools in your research.

Peeling away another layer, we get to Time Horizons . We distinguish between longitudinal research and cross-sectional research. Longitudinal research is characterised by the long-time span that the research has been undertaken for – this is often used with commissioned research projects where large funding pots are available. Cross-sectional research projects, on the other hand, are characterised by looking at a phenomenon within only a snapshot of time ( Saunders et al., 2019 ). Most dissertations are cross-sectional research projects as they have a previously defined deadline attached to them.

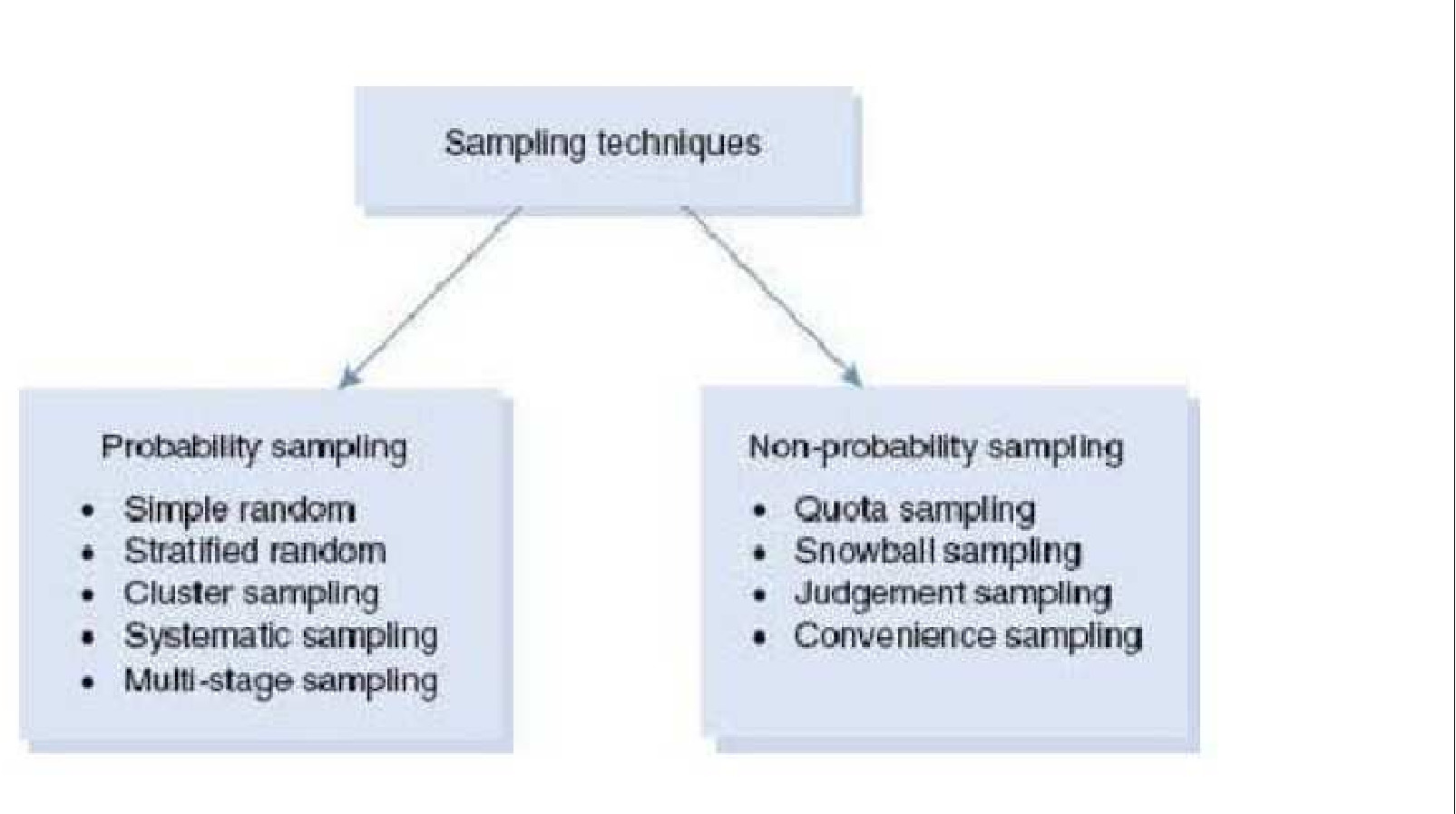

The centre of the onion is made up of Data Collection and Analysis . Before the data are collected, we need to have a look at Sampling . Your sampling directly depends upon the choices that you have made – your methods that you use in your research. Why do we use sampling? As it is unlikely to undertake research on the whole population, we utilise a smaller population ( Wilson, 2014 ). In some cases, you will find that your population is small enough to include them all ( Wilson, 2014 ). There are different sampling categories used depending on the type of method that you chose – quantitative or qualitative. Before you choose your sampling technique, you need to clearly define your target population ( Wilson, 2014 ). Who is it that you would like to ask and what are their characteristics? Think of gender, age, employment status, expertise or location to name a few possibilities. In quantitative sampling, we can choose between probability or random sampling. On the other hand, we choose from non-probability sampling when using qualitative methods ( Wilson, 2014 ; see Figure 5 ).

Two down arrows from sampling techniques is indicated toward probability and non-probability sampling techniques respectively. Probability sampling techniques comprises simple random, stratified random, cluster sampling, systematic sampling, and multi-stage sampling respectively. The non-probability sampling techniques comprises quota sampling, snowball sampling, judgement sampling, and convenience sampling respectively.

Figure. 3 Categories of sampling techniques

Source : Wilson (2014)

Once your data are collected, it has to be analysed in order to draw meaning from it. The first step should be organising your data ( Wilson, 2014 ). Some researchers also use specific software for this to add further rigour to their approach and receive a more detailed analysis. For example, the software SPSS is widely used for quantitative analysis, while NVivo and CAQDAS are widely used for qualitative analysis. It is also important that you know whether you are going to use deductive or inductive as your approach, as this depends on how you are going to present your data ( Wilson, 2014 ). With a deductive approach, you are going to follow the underlying theory, while with an inductive approach, you will need to analyse your data in a way so that you can receive new insights and potentially form or extend a framework.

Once these decisions are made, it is wise to choose from a number of different analysis types, depending on your method(s) chosen. In quantitative analysis, the statistical process to analyse your data has two different strands: descriptive statistics and inferential statistics ( Wilson, 2014 ). Descriptive analysis is used when you would like to describe your data, while the latter is appropriate when you would like draw conclusions from your data for the wider population ( Wilson, 2014 ). In a qualitative data analysis, you can choose from utilising a grounded theory analysis, a narrative analysis, a discourse analysis or a content analysis ( Wilson, 2014 ). A grounded theory analysis is defined by ( Glaser, 1992, p. 2 ; cited in Wilson, 2014 ) as ‘the systematic generating of theory from data, that itself is systematically obtained from social research’. So here, the theory is created from the data that was collected in your research and therefore follows an inductive approach ( Wilson, 2014 ). A narrative analysis is most appropriate when the researcher collected data that are sequential, such as stories or events across a certain timeline ( Wilson, 2014 ). Discourse analysis is best used when being presented with spoken or written data and the overarching focus here is the way in which language is being used within that data set ( Wilson, 2014 ). And lastly, content analysis is used to examine patterns in your data, such as how often a specific word was used or not used ( Wilson, 2014 ).

Qualitative Research Example

My research aim could be to investigate the barriers experienced by female entrepreneurs in the Scottish entrepreneurial ecosystem. I would likely choose Epistemology as my philosophy as it is concerned with how knowledge is created in the social realm and then choose Interpretivism as Philosophical Prism, because I want to acknowledge in my research that our reality is socially constructed and complex with multiple viewpoints to it. As my research concerns itself with shining light on new barriers and can therefore be called exploratory, it concerns itself with finding new data and developing theory afterwards. Hence, I would be using an inductive approach. My choice could be a case study or action research and would likely involve a single, qualitative method, such as focus groups or interviews. My sampling then is dependent on my choices – I am likely going to choose a convenient or purposive sampling technique and could even pair this with snowball sampling. I would use Nvivo for my analysis and I would likely choose between a discourse or content analysis.

Quantitative Research Example

My research aim could be to investigate the likelihood of women to be appointed as board members in social enterprises in Scotland, between 2018 and 2022. I would likely choose Ontology as my philosophy, because my research is about the reality that we live in. I would then go on to either choose Positivism or Pragmatism as philosophical prism, as my research is objective and is free of bias. I am likely be using deductive in my research making hypotheses as I go along in my literature review, which I want to test through my data collection tools. I might also have previous statistics/numerical data sets to inform my research. My strategy could be individual case studies, which are set out for each year between 2018 and 2022. I would likely utilise a single, quantitative method such as a questionnaire, which is then disseminated online through social media channels to test my hypotheses. My sampling is likely to be random or stratified sampling. I would use SPSS as software to analyse my data and then choose descriptive statistics if I wanted to display my data for each year; however, it might be useful to utilise inferential statistics to draw conclusions on the broader population.

Section Summary

- Understanding the language sitting behind the key concepts in business research methods is so important, as this informs your data collection tools, the robustness, reliability and novelty of your findings and your consequent analysis.

- The frequently used tool to showcase the complexity of research methods is Saunders et al., 2019 's Research Onion. You should be able to utilise this tool with each layer being peeled away, much like an onion.

- Two practical examples of a business research methods were outlined, which is meant to help the reader with the practical application of these concepts in their own research.

Mastering the Art of Research – Search Engines and Library Interfaces

In order for you to generate more than surface-level understanding of the terms touched upon earlier, you need to use your research skills. You need to utilise core textbooks that are outlined in the resource list in your research methods module to deepen your knowledge. It is recommended that you also review the recommended further reading for each section in this how-to guide. Once you have done this and you have more specific questions, it is advisable to consult your module tutor or your dissertation supervisor who can point you into the right direction.

Another key tool to master is the way of searching for something in a library interface as well as Google Scholar. Your university library will have search guides for your library search engine. Alternatively, you can consult a librarian to show you how to navigate the library interfaces for a meaningful search. Below, you can find two different approaches on how to search for relevant and contemporary publications.

In both interfaces, it is possible to search with keywords. Oftentimes, you are presented with keywords after the abstract of a journal article. These keywords are located at the beginning of the journal article. Once you have found or were presented with articles that contain keywords as part of your module, this is a great place to start. Alternatively, you can think about what you are looking for and then make up keywords by yourself. Keep in mind that you are likely looking for concepts that carry terminology, which is explained above. So, you will need to utilise this terminology in order for your search to bear fruit. You can also combine keywords in your search with AND as well as OR. Furthermore, you can search for a specific keyword phrase by including quotation marks before and after. There are some useful other parameters that can be included, such as relevance, date, language and type of publication.

Let us try this with an example: I am going to search for ‘ Business Research Methods ’ (with quotation marks) in Google Scholar and will use the filter on the date parameter, clicking on since 2021 . On the first page, I can find a number of widely cited, contemporary core textbooks on Business Research Methods. Utilising our other search possibilities, I am going to look for quantitative OR qualitative research methods in Google Scholar and sure enough, it shows me publications for both kinds of research methods. This should also work in your library interface, let us try it out!

Another method is the snowball technique whereby you search in publications that you have already found for other suitable publications, just like you might have done with the keyword search from the journal articles. In academic publishing, you always find a reference list at the end of the publication. Some core textbooks even include a recommended reading list per chapter. You again need some keywords that you are looking for, so you will need to take some time to consider what you are looking for and which terminology is likely used for these in the publications. You can then go through the reference list of your journal article/book or the recommended reading in the core textbook, scanning these for the keywords that you identified, either by title or by publisher/journal.

- You should now know why it is important to be able to search on your own for the publications that you are looking for.

- This section detailed that you could reach out to your librarian and dissertation supervisor for more information in order to learn more about search parameters to increase your ability to utilise the software that is available to you.

- You have been introduced to keyword searches, the parameters to consider during searches and how to create your own keywords. Furthermore, two approaches that can help you were outlined with an example for practical use.

The Importance of the Personal Link Between Language, Key Concepts and Researcher

The researcher can only uphold one’s responsibility to conduct rigorous, reliable, robust and ethically sound research once the language and key concepts are understood and can be applied accordingly. Furthermore, there are a number of procedures that need to be adhered to when collecting your primary data. These are set out in the Ethics Form that you have to complete before you can start your data collection. The Ethics Form is a crucial part in your research, as it seeks answers to questions about the reliability, robustness, ethicality, data storage and GDPR concerns of your research at this stage. Part of the ‘package’ is not only the Ethics Form, but also the consent form and drafts of your data collection tools. With qualitative data to be collected, you will include a separate consent form (orally or in written form) and that is shared with your participants. With quantitative data, the consent is obtained at the beginning of the data tool that is used, for example, a questionnaire. The drafts mentioned earlier could be an interview guide or a questionnaire draft. Your dissertation supervisor can support you further to help you make the right choices to conduct your research ethically.

On another note, I would like to go into more depth about the data collection drafts that are mentioned in the previous paragraph. It is crucial to think about the questions that you are going to include, as they determine the kind of data that you are going to receive. There are two types of questions that can be included: (1) descriptive questions and (2) exploratory or inferential questions ( Creswell, 2009 ). For example, you might want to conduct research on the evaluation measures of sustainability in Scottish SMEs in the clothing retail sector. You will want to find out what is important to the companies regarding sustainability and how they measure their impact in their sustainability report, potentially on the triple bottom line. A descriptive question usually warrants a Yes/No answer with little potential for deeper analysis, in this instance – ‘Do you know what the bottom line is? Yes/No’. Descriptive questions usually ask for definitions or facts and focus on a control variable ( Creswell, 2009 ). On the other hand, an exploratory or inferential question is used to find out more about the subject area by correlating independent and dependent variables ( Creswell, 2009 ). In this case, this could be ‘Which factors in your day-to-day operations have you considered that relate to your sustainability evaluation with the triple bottom line?’ Your language in your question has to change depending on what kind of data output you are looking for ( Creswell, 2009 ). With inferential or exploratory questions, correlations and/or comparisons can be established, while descriptive questions, as the name suggests, will have a descriptive data output ( Creswell, 2009 ). This is often the case when you have an underlying framework to your research question ( Creswell, 2009 ).

The other more commonly known types of questions are open, closed and static questions when designing your data collection tools ( Bell et al., 2022 ; Moser & Korstjens, 2018 ). Open questions are defined by the possibility for a range of potential answers, like the exploratory question above. While closed questions are characterised by an either-or answer, like our descriptive question, which can also include already predetermined answers for the participant who has to choose at least one of them.

The most important factor in asking questions, as well as the interplay between you, the research design and data collection, is bias. It is vital to consider your positionality within your research ( Peake et al., 2017 ; Sultana, 2007 ), particularly because bias cannot be fully eradicated in some research cases. This happens when the researcher becomes a part of the data collection process, for example during interviews, or is an insider to the phenomenon under study, which means that the researcher shares similar experiences to the participants. Here, it is then most important that you reflect on your position and your assumptions, experiences and prior knowledge before starting your data collection. By doing so, you can make sure that your assumptions and experiences do not interfere with your primary data.

The second point on bias is about asking questions without leading to a predisposed answer that you would like to hear. These are also called leading questions. These will likely sneak into your data collection draft if you are not aware of them. Let us stick with the research example from above on sustainability evaluation measures. You might choose a deductive approach with the triple bottom line as your underlying theory and have written up some hypotheses that you would like to test as part of the primary data collection. However, you realised that this might not get you the depth in data that you require, so you opted for mixed methods and incorporated a small sample of interviews as well. In the interview guide draft, you note ‘ I would like to inform you that it is good practice to consider the triple bottom line ’. Then you ask accordingly ‘ Do you measure or are you considering measuring your sustainability impact on the triple bottom line?’ – The likely answer that you will get from the participant is Yes. In this case, you have led your participant to believe that this is the right thing to do, so they will conform accordingly. If the participant had not received a qualifying sentence on the correctness of the triple bottom line, their answers might have been different. It is vital that you check your questions before you start your data collection. Your dissertation supervisor can also help you in understanding when a leading question is asked and how to reframe it.

- The researcher can only make ethically sound choices and fulfil his/her responsibility to conduct reliable, rigorous and robust research when the language and key concepts are fully understood.

- The types of questions that can be included and the data that you are going to receive from utilising these questions was discussed in this section.

- We have also reviewed the complexities that happen between you, the research design and the data collection tool as well as the considerations for eradicating bias in your research.

Becoming an Effective Researcher

In order to become an effective researcher yourself, I would like to manage your expectations of what lies ahead of you. This is by no means an easy journey to go on and you will need some resilience and grit to stick with your research. Now that you have made it this far, I am confident that you understand the key concepts and have some tools at your disposal to find the answers that you are looking for by yourself. Do not give up!

Additionally, you will not become an independent researcher overnight. It takes time to understand those concepts and incorporate them into your own research accordingly. Structuring your approach to understanding these key concepts is vital. I would like to recommend to you that you create a research time management plan for your knowledge increase. By doing so, you can divide each concept into smaller chunks and note down questions that you have as you go along.

Two strands of possible inquiry within research methods have emerged with a quick recap in Figure 3 and Figure 4 . These can help you to apply the key concepts in your own research and understand the bigger picture of the dichotomies that exist within business research methods. It is vital to note that in this how-to guide, dichotomies are used in order to make the logical progressions that traditionally takes place easier to understand; however, it is key that you understand that there can certainly be an overlap between these choices in some research designs ( Wilson, 2014 ).

- We discussed the soft skills needed in order to learn more about business research methods.

- Furthermore, some strategies on how to tackle your knowledge increase beyond this how-to guide were included in this section.

- You were given an overview of the two strands of inquiry that traditionally take place, which is meant to help you understand the bigger picture of business research methods and help you in your problem-solving abilities to keep on researching these concepts in order for you to be able to practically apply them yourself.

Includes a round-up of the methodological issues discussed in your guide . What can readers learn from this guide and apply to their own research?

In this how-to guide, the key concepts behind the language used to generate research methods as well as their importance to the overall process of research were identified, and Saunders et al., 2019 were utilised to break down the key concepts as well as their language that is used. Furthermore, you were able to see a qualitative and quantitative research example with the terminology included in these. In the second section, we explored how you can find useful and relevant sources to explore and increase your understanding of these concepts. In the third section, we discussed the importance of the personal link between the language, the key concepts and the researcher while shining light on the procedures that need following for ethically conducting research. In the last section, we gave you some tools to help you develop your problem-solving skills. In this section, you can also find an overview of the dichotomies present in business research methods, which is meant to help you to increase your ability to identify the practical applications that sit behind the language.

Multiple-Choice Quiz Questions

1. Which philosophical prisms are covered in this how-to guide?

Incorrect Answer

Feedback: This is not the correct answer. The correct answer is B.

Correct Answer

Feedback: Well done, correct answer

2. What are two types of sampling?

3. What are ‘leading questions’?

Feedback: This is not the correct answer. The correct answer is C.

Further Reading

Sign in to access this content, get a 30 day free trial, more like this, sage recommends.

We found other relevant content for you on other Sage platforms.

Have you created a personal profile? Login or create a profile so that you can save clips, playlists and searches

- Sign in/register

Navigating away from this page will delete your results

Please save your results to "My Self-Assessments" in your profile before navigating away from this page.

Sign in to my profile

Please sign into your institution before accessing your profile

Sign up for a free trial and experience all Sage Learning Resources have to offer.

You must have a valid academic email address to sign up.

Get off-campus access

- View or download all content my institution has access to.

Sign up for a free trial and experience all Sage Learning Resources has to offer.

- view my profile

- view my lists

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The purpose of this paper is to provide new researchers with a comprehensive overview of the main elements of research methodology, particularly in the business domain.

Research Methods in Business Studies. This accessible guide provides clear and practical explanations of key research methods in business studies, presenting a step-by-step approach to data collection, analysis, and problem solving.

What is business research? Business research helps companies make better business decisions by gathering information. The scope of the term business research is quite broad – it acts as an umbrella that covers every aspect of business, from finances to advertising creative.

Business Research. The purpose of business research is to gather information in order to aid business-related decision-making. Business research is defined as ‘the systematic and objective process of collecting, recording, analyzing and interpreting data for aid in solving managerial problems’.

The major research methods include risk assessment, statistics, sampling, hypothesis testing, surveys, and comparative analysis. It helps students develop solid knowledge and practical skills sufficient for conducting a research project from its initiation, through completion, and delivery.

Business research is conducted in five stages. The first stage is problem formation where the objectives of the research are established. The second stage is research design.

The framework for business research is divided into four parts: the research problem, research design, empirical evidence, and conclusion.

Research methodology determines how such investigation will take place and has been defined as “a way to systematically solve the research problem” (Kothari, 2004).

Explore the essential steps for data collection, reporting, and analysis in business research. Understanding Business Research offers a comprehensive introduction to the entire process of designing, conducting, interpreting, and reporting findings in the business environment.

This how-to guide identifies the key concepts behind the terminology that is used within business research methods and considers the importance of these key concepts to the overall research.