- Study and research support

- Academic skills

Dissertation examples

Listed below are some of the best examples of research projects and dissertations from undergraduate and taught postgraduate students at the University of Leeds We have not been able to gather examples from all schools. The module requirements for research projects may have changed since these examples were written. Refer to your module guidelines to make sure that you address all of the current assessment criteria. Some of the examples below are only available to access on campus.

- Undergraduate examples

- Taught Masters examples

| These dissertations achieved a mark of 80 or higher:

|

| The following two examples have been annotated with academic comments. This is to help you understand why they achieved a good 2:1 mark but also, more importantly, how the marks could have been improved. Please read to help you make the most of the two examples. (Mark 68) (Mark 66) These final year projects achieved a mark of a high first:

For students undertaking a New Venture Creation (NVC) approach, please see the following Masters level examples:

|

|

|

|

|

| Projects which attained grades of over 70 or between 60 and 69 are indicated on the lists (accessible only by students and staff registered with School of Computer Science, when on campus).

|

| These are good quality reports but they are not perfect. You may be able to identify areas for improvement (for example, structure, content, clarity, standard of written English, referencing or presentation quality).

|

|

|

| The following examples have their marks and feedback included at the end of of each document.

The following examples have their feedback provided in a separate document.

|

|

|

| School of Media and Communication . |

|

|

| The following outstanding dissertation example PDFs have their marks denoted in brackets. (Mark 78) (Mark 91) (Mark 85) |

| This dissertation achieved a mark of 84: . |

| LUBS5530 Enterprise

|

| MSc Sustainability

|

|

|

|

|

|

. |

| The following outstanding dissertation example PDFs have their marks denoted in brackets. (Mark 70) (Mark 78) |

AUP Students' Union

A Third Year's Top Tips on Writing Your Dissertation

Going into your third and final year of University can be a very daunting prospect, especially thinking about the dreaded dissertation. Having just handed in my own, I have definitely learnt many valuable lessons that I think can help those feeling nervous about getting started on their own in September. Here are some tips if you would like some of my third-year wisdom to help you in your writing!

Start early

This is probably the most important tip to take away from this post, as starting to plan your ideas and research as early as you can sets you up with a brilliant foundation. The first ideas you come up with will most likely be very different from your final question, but going through all of the options for your topic can help you realise which one is the strongest and most relevant to you. If you start too close to your deadline, you won't have this chance to explore your options meaning your ideas won't be as developed as if you had started earlier.

It's okay to change your question

Many people, like myself, go into the start of the year confident that they know the exact research question they want to use, but I can wholeheartedly say that neither I nor anyone I know stuck with their first idea! Whilst you might be reluctant to change your topic, just know it is a vital part of the process. The more you research into your chosen topic, the clearer it becomes on what your final question will be. I changed mine around 9 times before I finally settled on my research question, so don’t feel scared about changing your topic for the better.

Choose a topic you enjoy

The main reason I enjoyed writing my dissertation was that it was looking into a topic that I am extremely passionate about. It's so important that whatever you choose to write about is important to you as a creative, as why would you feel motivated to write about something that doesn’t interest you? Make sure that you choose a topic that makes you excited to write about it and to share your ideas with the reader.

Talk to your tutors

You'll be assigned a dissertation advisor to help guide you through your research which will most likely be one of your course tutors. Make sure that you raise any and all questions you might have about your essay, even those that might sound unimportant or embarrassing to ask. It's much better to be completely clear on what you're expected to do so you won't have to worry about it later on in your writing. Remember they are here to help you with anything you might need!

Academic resources

The Library staff have been invaluable to me and my classmates during our time studying at the University, especially during the writing of our dissertations. Whether you need help with Harvard Referencing (like me especially), research or the overall writing process, the staff in the Library can help you with most areas of your essay. You can book sessions with the staff on SmartHub, which I would highly recommend if you would like any further help with writing your dissertation.

Look after yourself

Finally, as much as hard work and dedication are important in writing your research paper, making sure you aren’t neglecting your own wellbeing is just as vital. It can be easy to overlook taking care of yourself when you’re working on something so important but just ensure you have plenty of downtime. Taking regular breaks, catching up with friends and family and making time for yourself are just as essential in making sure you’re doing your best work.

I hope these tips will be helpful to students going into their third year in September or anyone who might be worrying about writing their own dissertation. Remember to look after yourself and don't feel afraid to ask for help with you're writing if you

Elisabeth Montague

BA (Hons) Painting, Drawing and Printmaking

Recent Posts

8 Bits of 'Tech' to Make Studying Easier

Saving Money and Reducing Food Waste

The Low down on Plymouth's Art Fairs

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- Dissertation & Thesis Outline | Example & Free Templates

Dissertation & Thesis Outline | Example & Free Templates

Published on June 7, 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on November 21, 2023.

A thesis or dissertation outline is one of the most critical early steps in your writing process . It helps you to lay out and organize your ideas and can provide you with a roadmap for deciding the specifics of your dissertation topic and showcasing its relevance to your field.

Generally, an outline contains information on the different sections included in your thesis or dissertation , such as:

- Your anticipated title

- Your abstract

- Your chapters (sometimes subdivided into further topics like literature review, research methods, avenues for future research, etc.)

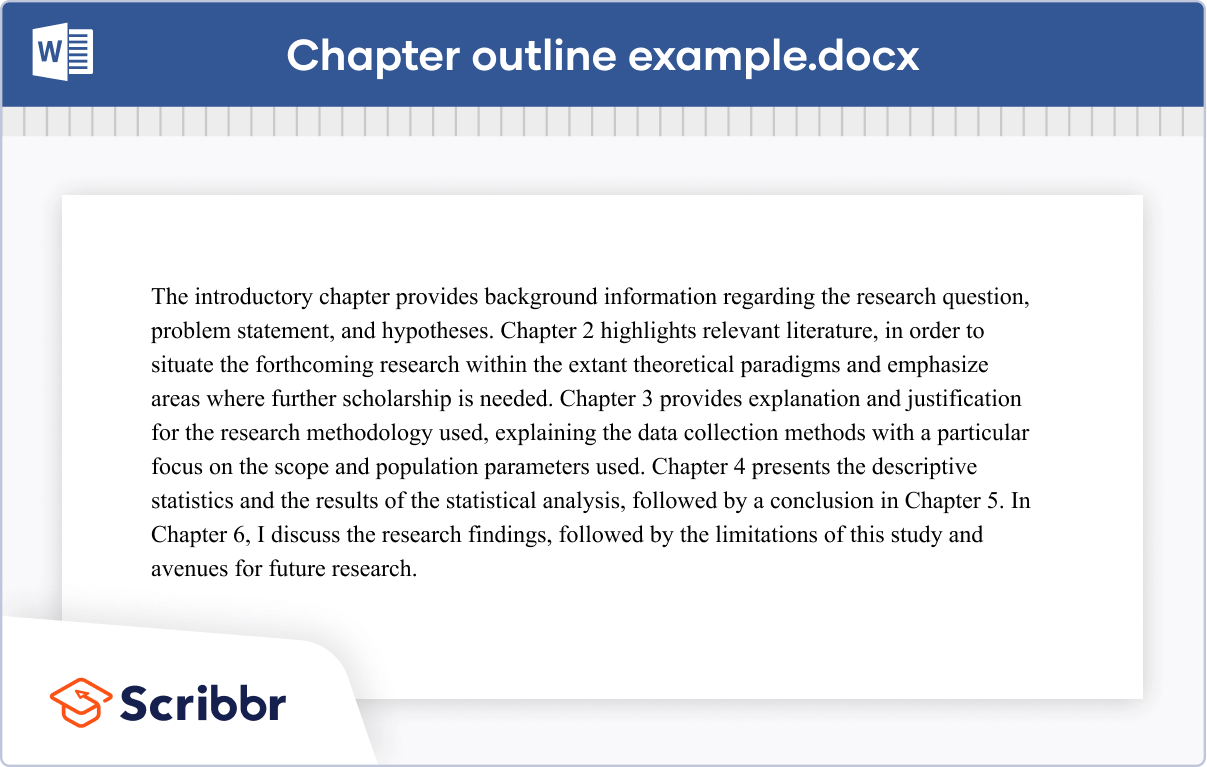

In the final product, you can also provide a chapter outline for your readers. This is a short paragraph at the end of your introduction to inform readers about the organizational structure of your thesis or dissertation. This chapter outline is also known as a reading guide or summary outline.

Table of contents

How to outline your thesis or dissertation, dissertation and thesis outline templates, chapter outline example, sample sentences for your chapter outline, sample verbs for variation in your chapter outline, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about thesis and dissertation outlines.

While there are some inter-institutional differences, many outlines proceed in a fairly similar fashion.

- Working Title

- “Elevator pitch” of your work (often written last).

- Introduce your area of study, sharing details about your research question, problem statement , and hypotheses . Situate your research within an existing paradigm or conceptual or theoretical framework .

- Subdivide as you see fit into main topics and sub-topics.

- Describe your research methods (e.g., your scope , population , and data collection ).

- Present your research findings and share about your data analysis methods.

- Answer the research question in a concise way.

- Interpret your findings, discuss potential limitations of your own research and speculate about future implications or related opportunities.

For a more detailed overview of chapters and other elements, be sure to check out our article on the structure of a dissertation or download our template .

To help you get started, we’ve created a full thesis or dissertation template in Word or Google Docs format. It’s easy adapt it to your own requirements.

Download Word template Download Google Docs template

It can be easy to fall into a pattern of overusing the same words or sentence constructions, which can make your work monotonous and repetitive for your readers. Consider utilizing some of the alternative constructions presented below.

Example 1: Passive construction

The passive voice is a common choice for outlines and overviews because the context makes it clear who is carrying out the action (e.g., you are conducting the research ). However, overuse of the passive voice can make your text vague and imprecise.

Example 2: IS-AV construction

You can also present your information using the “IS-AV” (inanimate subject with an active verb ) construction.

A chapter is an inanimate object, so it is not capable of taking an action itself (e.g., presenting or discussing). However, the meaning of the sentence is still easily understandable, so the IS-AV construction can be a good way to add variety to your text.

Example 3: The “I” construction

Another option is to use the “I” construction, which is often recommended by style manuals (e.g., APA Style and Chicago style ). However, depending on your field of study, this construction is not always considered professional or academic. Ask your supervisor if you’re not sure.

Example 4: Mix-and-match

To truly make the most of these options, consider mixing and matching the passive voice , IS-AV construction , and “I” construction .This can help the flow of your argument and improve the readability of your text.

As you draft the chapter outline, you may also find yourself frequently repeating the same words, such as “discuss,” “present,” “prove,” or “show.” Consider branching out to add richness and nuance to your writing. Here are some examples of synonyms you can use.

| Address | Describe | Imply | Refute |

| Argue | Determine | Indicate | Report |

| Claim | Emphasize | Mention | Reveal |

| Clarify | Examine | Point out | Speculate |

| Compare | Explain | Posit | Summarize |

| Concern | Formulate | Present | Target |

| Counter | Focus on | Propose | Treat |

| Define | Give | Provide insight into | Underpin |

| Demonstrate | Highlight | Recommend | Use |

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Research bias

- Anchoring bias

- Halo effect

- The Baader–Meinhof phenomenon

- The placebo effect

- Nonresponse bias

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

When you mention different chapters within your text, it’s considered best to use Roman numerals for most citation styles. However, the most important thing here is to remain consistent whenever using numbers in your dissertation .

The title page of your thesis or dissertation goes first, before all other content or lists that you may choose to include.

A thesis or dissertation outline is one of the most critical first steps in your writing process. It helps you to lay out and organize your ideas and can provide you with a roadmap for deciding what kind of research you’d like to undertake.

- Your chapters (sometimes subdivided into further topics like literature review , research methods , avenues for future research, etc.)

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, November 21). Dissertation & Thesis Outline | Example & Free Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved September 27, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/dissertation-thesis-outline/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, dissertation table of contents in word | instructions & examples, figure and table lists | word instructions, template & examples, thesis & dissertation acknowledgements | tips & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

Dissertation Structure & Layout 101: How to structure your dissertation, thesis or research project.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) Reviewed By: David Phair (PhD) | July 2019

So, you’ve got a decent understanding of what a dissertation is , you’ve chosen your topic and hopefully you’ve received approval for your research proposal . Awesome! Now its time to start the actual dissertation or thesis writing journey.

To craft a high-quality document, the very first thing you need to understand is dissertation structure . In this post, we’ll walk you through the generic dissertation structure and layout, step by step. We’ll start with the big picture, and then zoom into each chapter to briefly discuss the core contents. If you’re just starting out on your research journey, you should start with this post, which covers the big-picture process of how to write a dissertation or thesis .

*The Caveat *

In this post, we’ll be discussing a traditional dissertation/thesis structure and layout, which is generally used for social science research across universities, whether in the US, UK, Europe or Australia. However, some universities may have small variations on this structure (extra chapters, merged chapters, slightly different ordering, etc).

So, always check with your university if they have a prescribed structure or layout that they expect you to work with. If not, it’s safe to assume the structure we’ll discuss here is suitable. And even if they do have a prescribed structure, you’ll still get value from this post as we’ll explain the core contents of each section.

Overview: S tructuring a dissertation or thesis

- Acknowledgements page

- Abstract (or executive summary)

- Table of contents , list of figures and tables

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Literature review

- Chapter 3: Methodology

- Chapter 4: Results

- Chapter 5: Discussion

- Chapter 6: Conclusion

- Reference list

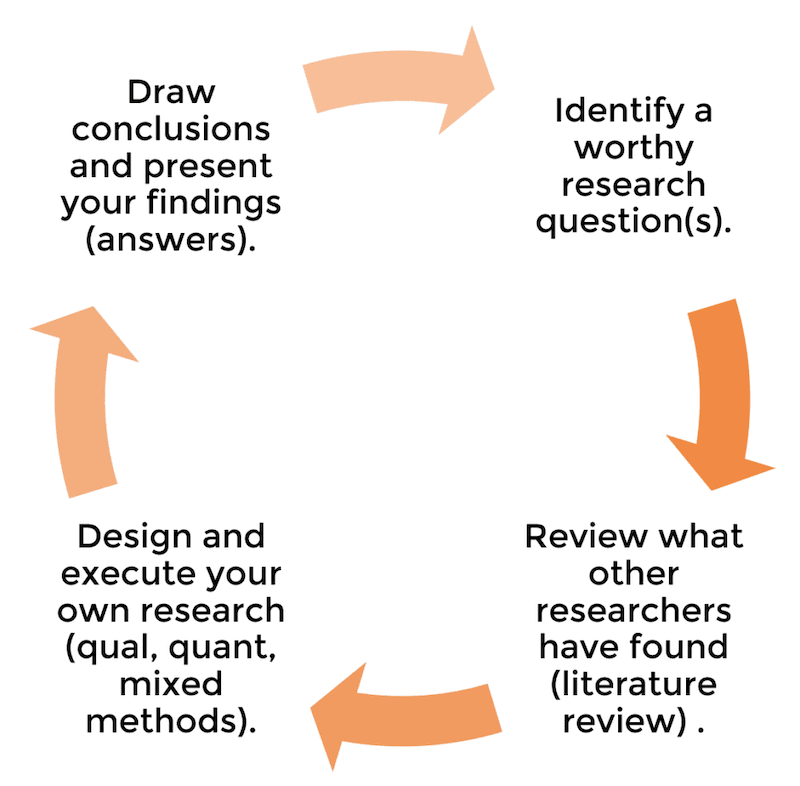

As I mentioned, some universities will have slight variations on this structure. For example, they want an additional “personal reflection chapter”, or they might prefer the results and discussion chapter to be merged into one. Regardless, the overarching flow will always be the same, as this flow reflects the research process , which we discussed here – i.e.:

- The introduction chapter presents the core research question and aims .

- The literature review chapter assesses what the current research says about this question.

- The methodology, results and discussion chapters go about undertaking new research about this question.

- The conclusion chapter (attempts to) answer the core research question .

In other words, the dissertation structure and layout reflect the research process of asking a well-defined question(s), investigating, and then answering the question – see below.

To restate that – the structure and layout of a dissertation reflect the flow of the overall research process . This is essential to understand, as each chapter will make a lot more sense if you “get” this concept. If you’re not familiar with the research process, read this post before going further.

Right. Now that we’ve covered the big picture, let’s dive a little deeper into the details of each section and chapter. Oh and by the way, you can also grab our free dissertation/thesis template here to help speed things up.

The title page of your dissertation is the very first impression the marker will get of your work, so it pays to invest some time thinking about your title. But what makes for a good title? A strong title needs to be 3 things:

- Succinct (not overly lengthy or verbose)

- Specific (not vague or ambiguous)

- Representative of the research you’re undertaking (clearly linked to your research questions)

Typically, a good title includes mention of the following:

- The broader area of the research (i.e. the overarching topic)

- The specific focus of your research (i.e. your specific context)

- Indication of research design (e.g. quantitative , qualitative , or mixed methods ).

For example:

A quantitative investigation [research design] into the antecedents of organisational trust [broader area] in the UK retail forex trading market [specific context/area of focus].

Again, some universities may have specific requirements regarding the format and structure of the title, so it’s worth double-checking expectations with your institution (if there’s no mention in the brief or study material).

Acknowledgements

This page provides you with an opportunity to say thank you to those who helped you along your research journey. Generally, it’s optional (and won’t count towards your marks), but it is academic best practice to include this.

So, who do you say thanks to? Well, there’s no prescribed requirements, but it’s common to mention the following people:

- Your dissertation supervisor or committee.

- Any professors, lecturers or academics that helped you understand the topic or methodologies.

- Any tutors, mentors or advisors.

- Your family and friends, especially spouse (for adult learners studying part-time).

There’s no need for lengthy rambling. Just state who you’re thankful to and for what (e.g. thank you to my supervisor, John Doe, for his endless patience and attentiveness) – be sincere. In terms of length, you should keep this to a page or less.

Abstract or executive summary

The dissertation abstract (or executive summary for some degrees) serves to provide the first-time reader (and marker or moderator) with a big-picture view of your research project. It should give them an understanding of the key insights and findings from the research, without them needing to read the rest of the report – in other words, it should be able to stand alone .

For it to stand alone, your abstract should cover the following key points (at a minimum):

- Your research questions and aims – what key question(s) did your research aim to answer?

- Your methodology – how did you go about investigating the topic and finding answers to your research question(s)?

- Your findings – following your own research, what did do you discover?

- Your conclusions – based on your findings, what conclusions did you draw? What answers did you find to your research question(s)?

So, in much the same way the dissertation structure mimics the research process, your abstract or executive summary should reflect the research process, from the initial stage of asking the original question to the final stage of answering that question.

In practical terms, it’s a good idea to write this section up last , once all your core chapters are complete. Otherwise, you’ll end up writing and rewriting this section multiple times (just wasting time). For a step by step guide on how to write a strong executive summary, check out this post .

Need a helping hand?

Table of contents

This section is straightforward. You’ll typically present your table of contents (TOC) first, followed by the two lists – figures and tables. I recommend that you use Microsoft Word’s automatic table of contents generator to generate your TOC. If you’re not familiar with this functionality, the video below explains it simply:

If you find that your table of contents is overly lengthy, consider removing one level of depth. Oftentimes, this can be done without detracting from the usefulness of the TOC.

Right, now that the “admin” sections are out of the way, its time to move on to your core chapters. These chapters are the heart of your dissertation and are where you’ll earn the marks. The first chapter is the introduction chapter – as you would expect, this is the time to introduce your research…

It’s important to understand that even though you’ve provided an overview of your research in your abstract, your introduction needs to be written as if the reader has not read that (remember, the abstract is essentially a standalone document). So, your introduction chapter needs to start from the very beginning, and should address the following questions:

- What will you be investigating (in plain-language, big picture-level)?

- Why is that worth investigating? How is it important to academia or business? How is it sufficiently original?

- What are your research aims and research question(s)? Note that the research questions can sometimes be presented at the end of the literature review (next chapter).

- What is the scope of your study? In other words, what will and won’t you cover ?

- How will you approach your research? In other words, what methodology will you adopt?

- How will you structure your dissertation? What are the core chapters and what will you do in each of them?

These are just the bare basic requirements for your intro chapter. Some universities will want additional bells and whistles in the intro chapter, so be sure to carefully read your brief or consult your research supervisor.

If done right, your introduction chapter will set a clear direction for the rest of your dissertation. Specifically, it will make it clear to the reader (and marker) exactly what you’ll be investigating, why that’s important, and how you’ll be going about the investigation. Conversely, if your introduction chapter leaves a first-time reader wondering what exactly you’ll be researching, you’ve still got some work to do.

Now that you’ve set a clear direction with your introduction chapter, the next step is the literature review . In this section, you will analyse the existing research (typically academic journal articles and high-quality industry publications), with a view to understanding the following questions:

- What does the literature currently say about the topic you’re investigating?

- Is the literature lacking or well established? Is it divided or in disagreement?

- How does your research fit into the bigger picture?

- How does your research contribute something original?

- How does the methodology of previous studies help you develop your own?

Depending on the nature of your study, you may also present a conceptual framework towards the end of your literature review, which you will then test in your actual research.

Again, some universities will want you to focus on some of these areas more than others, some will have additional or fewer requirements, and so on. Therefore, as always, its important to review your brief and/or discuss with your supervisor, so that you know exactly what’s expected of your literature review chapter.

Now that you’ve investigated the current state of knowledge in your literature review chapter and are familiar with the existing key theories, models and frameworks, its time to design your own research. Enter the methodology chapter – the most “science-ey” of the chapters…

In this chapter, you need to address two critical questions:

- Exactly HOW will you carry out your research (i.e. what is your intended research design)?

- Exactly WHY have you chosen to do things this way (i.e. how do you justify your design)?

Remember, the dissertation part of your degree is first and foremost about developing and demonstrating research skills . Therefore, the markers want to see that you know which methods to use, can clearly articulate why you’ve chosen then, and know how to deploy them effectively.

Importantly, this chapter requires detail – don’t hold back on the specifics. State exactly what you’ll be doing, with who, when, for how long, etc. Moreover, for every design choice you make, make sure you justify it.

In practice, you will likely end up coming back to this chapter once you’ve undertaken all your data collection and analysis, and revise it based on changes you made during the analysis phase. This is perfectly fine. Its natural for you to add an additional analysis technique, scrap an old one, etc based on where your data lead you. Of course, I’m talking about small changes here – not a fundamental switch from qualitative to quantitative, which will likely send your supervisor in a spin!

You’ve now collected your data and undertaken your analysis, whether qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods. In this chapter, you’ll present the raw results of your analysis . For example, in the case of a quant study, you’ll present the demographic data, descriptive statistics, inferential statistics , etc.

Typically, Chapter 4 is simply a presentation and description of the data, not a discussion of the meaning of the data. In other words, it’s descriptive, rather than analytical – the meaning is discussed in Chapter 5. However, some universities will want you to combine chapters 4 and 5, so that you both present and interpret the meaning of the data at the same time. Check with your institution what their preference is.

Now that you’ve presented the data analysis results, its time to interpret and analyse them. In other words, its time to discuss what they mean, especially in relation to your research question(s).

What you discuss here will depend largely on your chosen methodology. For example, if you’ve gone the quantitative route, you might discuss the relationships between variables . If you’ve gone the qualitative route, you might discuss key themes and the meanings thereof. It all depends on what your research design choices were.

Most importantly, you need to discuss your results in relation to your research questions and aims, as well as the existing literature. What do the results tell you about your research questions? Are they aligned with the existing research or at odds? If so, why might this be? Dig deep into your findings and explain what the findings suggest, in plain English.

The final chapter – you’ve made it! Now that you’ve discussed your interpretation of the results, its time to bring it back to the beginning with the conclusion chapter . In other words, its time to (attempt to) answer your original research question s (from way back in chapter 1). Clearly state what your conclusions are in terms of your research questions. This might feel a bit repetitive, as you would have touched on this in the previous chapter, but its important to bring the discussion full circle and explicitly state your answer(s) to the research question(s).

Next, you’ll typically discuss the implications of your findings . In other words, you’ve answered your research questions – but what does this mean for the real world (or even for academia)? What should now be done differently, given the new insight you’ve generated?

Lastly, you should discuss the limitations of your research, as well as what this means for future research in the area. No study is perfect, especially not a Masters-level. Discuss the shortcomings of your research. Perhaps your methodology was limited, perhaps your sample size was small or not representative, etc, etc. Don’t be afraid to critique your work – the markers want to see that you can identify the limitations of your work. This is a strength, not a weakness. Be brutal!

This marks the end of your core chapters – woohoo! From here on out, it’s pretty smooth sailing.

The reference list is straightforward. It should contain a list of all resources cited in your dissertation, in the required format, e.g. APA , Harvard, etc.

It’s essential that you use reference management software for your dissertation. Do NOT try handle your referencing manually – its far too error prone. On a reference list of multiple pages, you’re going to make mistake. To this end, I suggest considering either Mendeley or Zotero. Both are free and provide a very straightforward interface to ensure that your referencing is 100% on point. I’ve included a simple how-to video for the Mendeley software (my personal favourite) below:

Some universities may ask you to include a bibliography, as opposed to a reference list. These two things are not the same . A bibliography is similar to a reference list, except that it also includes resources which informed your thinking but were not directly cited in your dissertation. So, double-check your brief and make sure you use the right one.

The very last piece of the puzzle is the appendix or set of appendices. This is where you’ll include any supporting data and evidence. Importantly, supporting is the keyword here.

Your appendices should provide additional “nice to know”, depth-adding information, which is not critical to the core analysis. Appendices should not be used as a way to cut down word count (see this post which covers how to reduce word count ). In other words, don’t place content that is critical to the core analysis here, just to save word count. You will not earn marks on any content in the appendices, so don’t try to play the system!

Time to recap…

And there you have it – the traditional dissertation structure and layout, from A-Z. To recap, the core structure for a dissertation or thesis is (typically) as follows:

- Acknowledgments page

Most importantly, the core chapters should reflect the research process (asking, investigating and answering your research question). Moreover, the research question(s) should form the golden thread throughout your dissertation structure. Everything should revolve around the research questions, and as you’ve seen, they should form both the start point (i.e. introduction chapter) and the endpoint (i.e. conclusion chapter).

I hope this post has provided you with clarity about the traditional dissertation/thesis structure and layout. If you have any questions or comments, please leave a comment below, or feel free to get in touch with us. Also, be sure to check out the rest of the Grad Coach Blog .

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

36 Comments

many thanks i found it very useful

Glad to hear that, Arun. Good luck writing your dissertation.

Such clear practical logical advice. I very much needed to read this to keep me focused in stead of fretting.. Perfect now ready to start my research!

what about scientific fields like computer or engineering thesis what is the difference in the structure? thank you very much

Thanks so much this helped me a lot!

Very helpful and accessible. What I like most is how practical the advice is along with helpful tools/ links.

Thanks Ade!

Thank you so much sir.. It was really helpful..

You’re welcome!

Hi! How many words maximum should contain the abstract?

Thank you so much 😊 Find this at the right moment

You’re most welcome. Good luck with your dissertation.

best ever benefit i got on right time thank you

Many times Clarity and vision of destination of dissertation is what makes the difference between good ,average and great researchers the same way a great automobile driver is fast with clarity of address and Clear weather conditions .

I guess Great researcher = great ideas + knowledge + great and fast data collection and modeling + great writing + high clarity on all these

You have given immense clarity from start to end.

Morning. Where will I write the definitions of what I’m referring to in my report?

Thank you so much Derek, I was almost lost! Thanks a tonnnn! Have a great day!

Thanks ! so concise and valuable

This was very helpful. Clear and concise. I know exactly what to do now.

Thank you for allowing me to go through briefly. I hope to find time to continue.

Really useful to me. Thanks a thousand times

Very interesting! It will definitely set me and many more for success. highly recommended.

Thank you soo much sir, for the opportunity to express my skills

Usefull, thanks a lot. Really clear

Very nice and easy to understand. Thank you .

That was incredibly useful. Thanks Grad Coach Crew!

My stress level just dropped at least 15 points after watching this. Just starting my thesis for my grad program and I feel a lot more capable now! Thanks for such a clear and helpful video, Emma and the GradCoach team!

Do we need to mention the number of words the dissertation contains in the main document?

It depends on your university’s requirements, so it would be best to check with them 🙂

Such a helpful post to help me get started with structuring my masters dissertation, thank you!

Great video; I appreciate that helpful information

It is so necessary or avital course

This blog is very informative for my research. Thank you

Doctoral students are required to fill out the National Research Council’s Survey of Earned Doctorates

wow this is an amazing gain in my life

This is so good

How can i arrange my specific objectives in my dissertation?

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- What Is A Literature Review (In A Dissertation Or Thesis) - Grad Coach - […] is to write the actual literature review chapter (this is usually the second chapter in a typical dissertation or…

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- StudySkills@Sheffield

- Research skills

- Research methods

How to plan a dissertation or final year project

Information on how to plan and manage your dissertation project.

What is research?

Research sometimes just means finding out information about a topic. However, research in an academic context refers to a more rigorous process that, when undertaken effectively, will lead to new insights or perspectives.

The classic definition of academic research is that it leads to an original 'contribution to knowledge' in a particular field of inquiry by identifying an important question or problem and then answering or solving it in a systematic way.

The University of Sheffield prides itself on being a research-led university . Crucially, this means that teaching is informed by cutting-edge research in the academic field.

It also means that you are learning in an environment where you develop and use research skills as you progress. Your dissertation or final-year project is a chance to put all of this experience together and apply it to make your own contribution to knowledge in your own narrow and specific area of interest.

It also presents a number of new challenges relating to the scale, scope and structure of a piece of work that is likely to be more substantial than any you have undertaken before. These resources will help you to break the process down and explore ways to plan and structure your research and organise your written work.

Dissertation Planning Essentials workshop: book here

Defining your project

A good research project will be as narrowly defined and specific as possible to allow you to explore the area as fully as possible within the time and space constraints that you are facing. But how do you go from a general area of interest to a fully-formed research project?

This Project Design Template will help you to work through this process. Access the template and read more about how to use it below.

Access the Project Design Template (google doc)

Your dissertation or final-year research topic

You may have lots of ideas of things you would like to explore in your project; you may not be sure where to start. Either way, writing down some relevant key words is a good first step to help you to identify the area(s) of interest.

Once you have some key words in place, can you break them down further to identify any sub-topics of interest. For example if you are interested in sustainable building design, what is it about that topic that you would like to find out more about? The use of green walls? Natural light? Air circulation? Are you interested in civic buildings, schools or homes? Do you have a geographical area of focus in mind?

Once you have your key words and sub topics in place, you can have a go at formulating them into a mission statement for your project setting out exactly what it is you want to achieve. For example, ‘This project will compare the use of natural air circulation design features in Chinese and British school buildings.’

Don’t forget, your mission statement is something that you can keep coming back to and tweaking as your project takes shape.

Relevant literature

How much do you need to read to develop your literature review? There is no simple answer to this question and the answer will depend on your project and its scope. However, you can help to answer that question yourself by identifying the key themes from the literature that you will need to include in your review. Aim for somewhere between 3-5 themes to help create a structured and focused literature review.

Once you have your themes in place, you will need to identify the key texts that have informed your thinking. Try to aim for 3-5 sources per theme and make sure you have included the most influential and the most recent research within that list.

Book workshops on Dissertation Writing: Effective Paraphrasing, Summarising and Referencing, Writing Persuasive Introductions, Conclusions and Discussions, and Writing Effective Thesis Statements and Topic Sentences.

More information

Book a writing advisory service appointment for feedback on your work and advice on dissertation writing

make an appointment (student login required)

Your research

What is it that you want to find out, explore or test in your research? Most research projects will involve several research objectives that will allow you to fulfil your mission statement. Aim to begin with the broadest, most significant objective and try to keep the number of objectives manageable to maintain focus.

What data or information will you need to collect in order to meet each objective? Remember that the data that you use for your research will need to be valid, sufficient, reliable and feasible within the timeframe. You can find out more about how to develop your research methodology in order to collect this information on our How to identify your research methods page.

- How to identify your research methods

Project planning

The key to completing a research project successfully is to invest time in planning and organising your project.

A student research project, whether a dissertation or a research placement, will usually involve tight timescales and deadlines. Given the wealth of tasks involved in a typical dissertation project, this can seriously limit the time available for actual data collection or research.

As an early stage of the planning process, have a go at breaking your project down into its constituent parts: i.e. all of the tasks that you will need to complete between now and the deadline. How long will each of them take? For example:

|

|

|

|

| Background reading | 3 weeks | 2 May |

| Literature review | 2 weeks | 16 May |

| Design and write methodology | 1 week | 23 May |

| Ethics review | 3 weeks | 14 June |

| Data collection | 2 weeks | 28 June |

| Data analysis | 2 weeks | 11 july |

| Produce figures | 1 week | 18 July |

| Write discussion | 1 week | 25 July |

| Draft to supervisor | 1 week | 1 August |

| Act on feedback | 3 days | 20 August |

| Formatting and bibliography | 2 days | 28 August |

| Editing and proofreading | 2 days | 1 September |

Using Generative AI for planning

You may want to consider using a Generative AI tool to help with the planning process. The key things to consider in your approach to planning with GenAI are the following:

- Provide as much detail as possible about your schedule and requirements when you are designing your initial prompt.

- Be sure to build some contingency time into the plan to allow for unforeseen eventualities.

- You may need to use multiple prompts to refine and tweak the output to generate a plan that works for you.

- You will need to sense check the output to ensure that it is realistic and meets your needs.

Generative AI can help you to plan an overall schedule for your project and/or break down individual tasks. The following prompts may give you some inspiration for how to use GenAI to plan your dissertation project:

[PROMPT] I am a [final year undergraduate] student planning a dissertation project. I have an intermediate deadline for my literature review on [15th April 2025]. The word count for the literature review is [3000 words]. I will be on holiday from [1 April-11 April 2025]. I would like to spend [7] hours per week on this. Create a plan to help me meet this deadline.

[PROMPT] I am a [masters] student planning a dissertation project. My research will involve [a survey] with a goal of receiving [100 responses]. I need to have this data by [20 May]. What key stages do I need to include in my planning process?

Visit How to use Generative AI for productivity for further information.

Project management

Once you have an idea of the tasks involved in your project and the rough timescales that you intend to work towards, you will need to make sure that you have a strategy in place to monitor your progress and stay on track.

You might want to consider using one or more of the following strategies to manage your time on your dissertation project.

A simple timeline can be a clear visual way to keep track of tasks and organise them chronologically.

Try using a large sheet of paper with a timeline drawn across the middle horizontally. Add tasks and deadlines to post-it notes and arrange them along the timeline, overlapping where the tasks allow it.

Stick your timeline on the wall behind your desk and cross off tasks as you complete them, or move them around and add to them if your plans change or new tasks arise along the way.

Gantt charts

A Gantt chart provides a more structured visual representation of your project and its milestones.

Identify tasks in order down the left-hand side of the chart, identify deadlines and colour in the corresponding number of days or weeks that you anticipate the task will take.

A Gantt chart will allow you to identify high priority ‘blocker’ tasks that need to be completed before subsequent tasks can be ‘unlocked’. For example, your ethics review will need to be complete before you are able to move onto data collection.

You can access a free Gantt chart template via Google sheets.

Access a free Gantt chart template (Google Sheets)

Google Calendar

Google Calendar is a powerful tool to help manage your time on an independent research project. The following steps will help you to make the most of your calendar to organise the individual tasks relating to your project:

- Add the milestones that you have identified to the top bar of your calendar.

- Block out any existing or planned other commitments in your calendar to help you to keep track of how much time you have available to devote to your project.

- Plan ahead and identify blocks of time that you can spend working on your dissertation, aiming to keep this as protected project time.

- Using your task list and your milestones, identify what specifically you intend to use each block of time to work on and add it to the event in your calendar.

Planning ahead and committing this time to your dissertation will help you to sense check the time you have available and stick to your plan.

Trello is a simple and accessible online tool that allows you to identify and colour code tasks, set yourself deadlines and share your project plan with collaborators

You can use Trello to create a project ‘workflow’ with tasks allocated to the following sections:

- Low priority: the tasks that are coming up in the future but which you don’t need to worry about right now.

- High priority: the tasks that you will need to start working on soon or as a matter of urgency.

- In progress: the tasks that you are actively working on now. Try to keep the number of in-progress tasks to a minimum to maintain your focus.

- Under review: you may need to share progress with your supervisor or want to review things yourself. Keep tasks here until you feel they are complete.

- Complete: tasks that are now finished and will need no further attention.

Over the course of a project like a dissertation, you will hopefully see all of your tasks move from low priority through the workflow to the point of completion. You can see an example Dissertation Planning Trello board here and some guidance for students on using Trello (Linked In Learning).

View an example Trello board Access guidance on using Trello (LinkedIn Learning)

Working with your supervisor

Your supervisor will be your first point of contact for advice on your project and to help you to resolve issues arising.

Remember, your supervisor will have a busy schedule and may be supervising several students at once. Although they will do their best to support you, they may not be able to get back to you right away and may be limited in their availability to meet you.

There are a number of things that you can do to make the most out of the relationship. Some strategies to consider include:

- Share plans/ideas/work-in-progress with your supervisor early

- Plan for meetings, sketch out an informal agenda

- Write down your main questions before the meeting. Don’t leave without answers!

- Be receptive to feedback and criticism

- Take notes/record the meeting on a smartphone (with your supervisor’s permission!)

To find out more about how to get the most out of working with your supervisor, explore our interactive digital workshop.

Launch the Supervisor/Supervisee Relationships interactive workshop

- Read other dissertations from students in your department/discipline to get an idea of how similar projects are organised and presented.

- Break your project down into its constituent parts and treat each chapter as an essay in its own right.

- Choose a topic that interests you and will sustain your interest, not just for a few days, but for a few months!

- Write up as you go along - writing can and should be part of all stages of the dissertation planning and developing process.

- Keep good records – don’t throw anything out!

- If in doubt, talk to your supervisor.

- How to write a literature review

- How to gain ethical approval

Further resources

- University of Sheffield Library Research Skills for Dissertations Library Guide

Use your mySkills portfolio to discover your skillset, reflect on your development, and record your progress.

Writing the Dissertation - Guides for Success: Writing the Dissertation Homepage

- Writing the Dissertation Homepage

- Overview and Planning

- Research Question

- Literature Review

- Methodology

- Results and Discussion

An introduction to writing your dissertation

Dissertations are often included in third year undergraduate work, as well as forming an important part of any Masters level programme.

A dissertation provides you with an opportunity to work independently, at length, on a topic that particularly interests you. It is also an effective means of research training, which helps to develop advanced intellectual skills such as evaluation, analysis and synthesis, as well as management skills.

Our Writing the Dissertation guides provide advice about how to approach, undertake and evaluate your own dissertation, so that you can make the most of this challenge.

Note: The contents of the dissertation guides aren't tailored to specific academic subject areas, but writing conventions do vary across disciplines . Therefore, it is important that you adapt the guidance to meet the particular requirements of your discipline.

How to use our guides for success

Our dissertation writing guides begin with the Overview and Planning process, including developing a Research Question , then move through common sections of the writing: Literature Review , Methodology , Results and Discussion , and Conclusion. You can navigate the guides using the tabs above. You can also access the guides through our Dissertation Planner tool.

However, as you explore the guides, please keep in mind that the writing process is recursive and won't progress in a wholly linear fashion. Thus, whilst the guides are arranged 'chronologically', feel free to move between them and study their contents in whatever order best suits your approach and project.

We also host Academic Skills Drop-Ins, Maths/Stats Drop-Ins, Writing Cafes, and other events to support you. Check out our Here to Help page to see the weekly schedule of events .

- Next: Overview and Planning >>

- Last Updated: Sep 13, 2024 9:48 AM

- URL: https://library.soton.ac.uk/writing_the_dissertation

Dissertation tips from a third year

Ah, dissertations. The 10,000 word assignment that every student seems to dread. It certainly sounds terrifying, but once you get stuck in, it isn’t as bad as you’d think. My deadline is in a couple of weeks and, even as someone with a serious stress problem, I’m not too worried about it. If you follow a few of my tips then there’s no need to worry either.

Firstly, it’s worth noting that I’m writing a Creative Writing dissertation rather than a research dissertation for my English degree. The difference is, I have to write 8,000 words of prose or poetry and then a 2,000 word critique of my own work. The challenge appealed to me and I’d never turn down a chance to be creative. But, with all of its merits, there are still difficulties, which I have acquired some tips for!

Particularly with creative writing, it isn’t always best to go with the first idea you have. I must have come up with at least five different ideas before settling on the one I have now and to be honest, I’ve probably had better ideas since!

Lots of people don’t plan before they start writing but I feel like a dissertation isn’t something you can just wing. 10,000 words sounds like a lot but with a short story, it’s hard to fit a developed plot within that word count. I had to plan each chapter to make sure I didn’t miss anything out.

Writer’s block

So many times over the past few months, I’ve been struck with writer’s block. I stared at a blank page with no idea what to write next, but the main thing I’ve learnt is to do the exact opposite. When you can’t think of what to write, don’t! Go out for a walk, clean your room, do something menial that requires little brain power – subconsciously, you’ll be mulling over ideas and often, that’s when you’ll crack what to write next.

This is both the easiest and hardest thing to do but don’t be afraid to cut big chunks of writing out, as painful as it might be. Also, spelling, punctuation and grammar (as condescending as that sounds) are so important, you could easily lose marks for these not being perfect – I would definitely recommend getting someone else to read it as a second pair of eyes.

See your dissertation tutor!

This one probably sounds obvious too, but so many people skip the chance to get feedback throughout the writing process. Your tutor is there for a reason and will likely make your work a lot better if you submit it regularly for review. Remember that you can also go and see your Academic Subject Librarians for some support with referencing, research and other key areas of your dissertation.

I suppose in a weird way, the final thing would be to enjoy it. A lot of people have the choice and still opt to do a dissertation for that sense of pride of writing such a huge project. It’s a massive achievement and handing in a completed dissertation (that you’ve probably bled, sweat and cried over!) is a great way to end your time at university.

If you’re still struggling with your diss, check out Emily’s vlog over on the Student Life YouTube channel:

This article is featured on Learning at Lincoln .

Please note: This content was created prior to Coronavirus, and some things might be different due to current laws and restrictions. Please refer to the University of Lincoln for the latest information.

- Undergraduate

Meet the author

We use cookies to understand how visitors use our website and to improve the user experience. To find out more, see our Cookies Policy .

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Writing your third year psychology dissertation in the UK: A practical guide

Related Papers

Mohd Helmy Hakimie Mohd Rozlan

Md Amir Hossain

Md Ekram Hossain

Nguyen Phuoc Bao An

This is the first comprehensive guide to the range of research methods available to applied psychologists. Ideally suited to students and researchers alike, and covering both quantitative and qualitative techniques, the book takes readers on a journey from research design to final reporting. The book is divided into four sections, with chapters written by leading international researchers working in a range of applied settings: • Getting Started • Data Collection • Data Analysis • Research Dissemination With coverage of sampling and ethical issues, and chapters on everything from experimental and quasi-experimental designs to longitudinal data collection and focus groups, the book provides a concise overview not only of the options available for applied research but also of how to make sense of the data produced. It includes chapters on organisational interventions and the use of digital technologies and concludes with chapters on how to publish your research, whether it's a thesis, journal article or organisational report. This is a must-have book for anyone conducting psychological research in an applied setting. Paula Brough is Professor of Organisational Psychology in the School of Applied Psychology, Griffith University, Australia. Paula conducts research in organisational psychology with a specific focus on occupational health psychology. Paula's primary research areas include: occupational stress, employee health and well-being, work-life balance and the psychosocial work environment. Paula assesses how work environments can be improved via job redesign, supportive leadership practices and enhanced equity to improve employee health, work commitment and productivity. Paula is an editorial board member of the Journal of Organisational Behavior, Work and Stress and the International Journal of Stress Management.

Abigael Maan Escobar

Before, price and quality completely dominate the buying decision of consumers, but in this era, where consumers are mostly millennials who are more careful and cautious with what they buy, corporate social responsibility (CSR) is now considered as a purchase criterion. This study further examined the role of the five dimensions of CSR (economic, legal, ethical, philanthropic, and environmental) as a predictor of consumer buying behaviour of millennials in the Philippines. The relationship between CSR and consumer buying behaviour was measured in a cross-sectional study design. Both quantitative (online survey) and qualitative (in-depth interview) research methods were adopted by the researcher. For quantitative data, 150 respondents were chosen using non-probability sampling technique. The respondents answered an online questionnaire regarding their knowledge level on CSR, CSR and stakeholders’ expectations in businesses, and CSR and buying behaviour. For the qualitative data, six in-depth interview participants were randomly selected from the Business Administration (BA) students of Southville International School Affiliated with Foreign Universities (SISFU). The researcher used the semi-structured interview guide from Geokhaji’s (2015) study. Through multiple linear regression, significant relationship was found between philanthropic responsibility and consumer buying behaviour, showing that millennials in the Philippines would buy more from companies engaging in philanthropic activities. The qualitative results also showed that millennials consider philanthropic responsibility as the most important CSR dimension. However, huge regard on environmental responsibility was also demonstrated by the in-depth interview participants. Difference in methodology can shine light on this contradicting findings. It is hypothesized that the open-ended questions for in-depth interview, allowed the participants to specifically state their favoured environmental activities that are not given in the online survey. Nonetheless, consistency of quantitative and qualitative results that millennials in the Philippines consider philanthropic responsibility the most was evident.

Some women experience premenstrual syndrome (PMS), and its more severe presentation as premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), which seriously limits their coping ability in daily life, including their parenting ability. Social workers routinely assess parenting ability, giving rise to the question, “How does the premenstrual knowledge of social workers influence whether and what they ask in their assessment practices with mothers?” The heavily debated premenstrual literature rests on four approaches. After these perspectives, an enhanced biopsychosocial framework (BPS-E) is used to examine the premenstrual knowledge of social workers and their conversations about PMS/PMDD as they assess women’s parenting. This exploratory study used a triangulated convergence design, generating data from both quantitative and qualitative methodologies. In the first phase, 521 social workers completed a Premenstrual Experience Knowledge Questionnaire (PEKQ) created for this research. In the qualitative phase, inspired by an interpretative phenomenological approach, 16 social workers described in interviews their premenstrual knowledge and its impact, if any, on their assessment practices with mothers. Most social workers had limited knowledge of PMS/PMDD, most crucially a) the PMDD DSM-V classification, b) increased suicide attempts during the premenstruum, and c) the effectiveness of SSRI anti-depressants in moderating the symptoms of PMDD. Also, the greater the interference of social workers’ own premenstrual symptoms on their daily living and the more premenstrual training they had received, the higher their premenstrual knowledge scores. Very few social workers in this study (5.1%) addressed premenstrual symptoms with their female clients. However, a statistically significant relationship existed in this sample between asking female clients about PMS/PMDD and social workers’ (a) age, (b) premenstrual knowledge scores, (c) premenstrual training, and (d) the degree to which the premenstrual symptoms of female social workers interfered in their own daily living. These results can direct social work education and practice. Not asking about PMS/PMDD symptoms could have negative outcomes, particularly in child protection, where the safety needs of children could remain unaddressed. Conversely, women who tell uninformed or disapproving social workers about their premenstrual symptoms might be further subjected to mother-blame, stigmatization, or punitive interventions.

Lynn E Barry

Some women experience premenstrual syndrome (PMS), and its more severe presentation as premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), which seriously limits their coping ability in daily life, including their parenting ability. Social workers routinely assess parenting ability, giving rise to the question, “How does the premenstrual knowledge of social workers influence whether and what they ask in their assessment practices with mothers?” The heavily debated premenstrual literature rests on four approaches. After these perspectives, an enhanced biopsychosocial framework (BPS-E) is used to examine the premenstrual knowledge of social workers and their conversations about PMS/PMDD as they assess women’s parenting. This exploratory study used a triangulated convergence design, generating data from both quantitative and qualitative methodologies. In the first phase, 521 social workers completed a Premenstrual Experience Knowledge Questionnaire (PEKQ) created for this research. In the qualitative phase, inspired by an interpretative phenomenological approach, 16 social workers described in interviews their premenstrual knowledge and its impact, if any, on their assessment practices with mothers. Most social workers had limited knowledge of PMS/PMDD, most crucially a) the PMDD DSM-V classification, b) increased suicide attempts during the premenstruum, and c) the effectiveness of SSRI anti-depressants in moderating the symptoms of PMDD. Also, the greater the interference of social workers’ own premenstrual symptoms on their daily living and the more premenstrual training they had received, the higher their premenstrual knowledge scores. Very few social workers in this study (5.1%) addressed premenstrual symptoms with their female clients. However, a statistically significant relationship existed in this sample between asking female clients about PMS/PMDD and social workers’ (a) age, (b) premenstrual knowledge scores, (c) premenstrual training,and (d) the degree to which the premenstrual symptoms of female social workers interfered in their own daily living. These results can direct social work education and practice. Not asking about PMS/PMDD symptoms could have negative outcomes, particularly in child protection, where the safety needs of children could remain unaddressed. Conversely, women who tell uninformed or disapproving social workers about their premenstrual symptoms might be further subjected to mother-blame, stigmatization, or punitive interventions.

Marco Antonio Perez

research methodology

Musangamfura Vincent

Research Methods: The Basics is an accessible, user-friendly introduction to the different aspects of research theory, methods and practice. Structured in two parts, the first covering the nature of knowledge and the reasons for research, and the second the specific methods used to carry out effective research, this book covers: structuring and planning a research project the ethical issues involved in research different types of data and how they are measured collecting and analysing data in order to draw sound conclusions devising a research proposal and writing up the research. Complete with a glossary of key terms and guides to further reading, this book is an essential text for anyone coming to research for the first time, and is widely relevant across the social sciences and humanities. Nicholas Walliman is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Architecture at Oxford Brookes University, UK.

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Lindsy Richardson

Xinxing Jiang

Stephanie Brooks

Jiselle Denise Lim

Yasmin Yusuf

Daniel Woods

Christopher Ryan

ismail samad

dammam aldammam

Tsadiku Setegn

Silvia Cont

Pamela Orozco Márquez

Ashley Grosso

Dr. Fredrick Ssempala (Ph.D.) , James Lam Lagoro

kingsley Daraojimba

Tejaswini Kotian

Nguyễn Hoan

Journal of Medical Ethics

Sara Nora Ross

Sarada Dhakal

Journal for New Generation Sciences

Hermanus Moolman

Wafaa Almotawah

Training and Education in Professional Psychology

Nicholas Ladany

James M. Lashbrooke

Journal of Counseling …

Timothy B. Smith

Dessalegn Fufa

Cyril Jeusset

Kathryn Dekas

Daniel Parker

Transforming Research Methods in the Social Sciences: Case studies from South Africa

Prof Elizabeth (Liz) Archer

Faruk Zulkarnaini

Zain Ul Hussain

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Planning your PhD research: A 3-year PhD timeline example

Planning out a PhD trajectory can be overwhelming. Example PhD timelines can make the task easier and inspire. The following PhD timeline example describes the process and milestones of completing a PhD within 3 years.

Elements to include in a 3-year PhD timeline

What to include in a 3-year PhD timeline depends on the unique characteristics of a PhD project, specific university requirements, agreements with the supervisor/s and the PhD student’s career ambitions.

For instance, some PhD students write a monograph while others complete a PhD based on several journal publications. Both monographs and cumulative dissertations have advantages and disadvantages , and not all universities allow both formats. The thesis type influences the PhD timeline.

The most common elements included in a 3-year PhD timeline are the following:

The example scenario: Completing a PhD in 3 years

Many (starting) PhD students look for examples of how to plan a PhD in 3 years. Therefore, let’s look at an example scenario of a fictional PhD student. Let’s call her Maria.

In order to complete her PhD programme, Maria also needs to complete coursework and earn 15 credits, or ECTS in her case.

Example: planning year 1 of a 3-year PhD

Most PhD students start their first year with a rough idea, but not a well-worked out plan and timeline. Therefore, they usually begin with working on a more elaborate research proposal in the first months of their PhD. This is also the case for our example PhD student Maria.

Example: Planning year 2 of a 3-year PhD

Example: planning year 3 of a 3-year phd, example of a 3 year phd gantt chart timeline.

Combining the 3-year planning for our example PhD student Maria, it results in the following PhD timeline:

Final reflection

In fact, in real life, many PhD students spend four years full-time to complete a PhD based on four papers, instead of three. Some extend their studies even longer.

Master Academia

Get new content delivered directly to your inbox, 10 amazing benefits of getting a phd later in life, how to prepare your viva opening speech, related articles, ten reasons to pursue an academic career, finish a phd (in time) by choosing the right project, journal editors: what they do, and how to become one, the best answers to “why do you want to do a phd”.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

Prize-Winning Thesis and Dissertation Examples

Published on 9 September 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on 6 April 2023.

It can be difficult to know where to start when writing your thesis or dissertation . One way to come up with some ideas or maybe even combat writer’s block is to check out previous work done by other students.

This article collects a list of undergraduate, master’s, and PhD theses and dissertations that have won prizes for their high-quality research.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Award-winning undergraduate theses, award-winning master’s theses, award-winning ph.d. dissertations.

University : University of Pennsylvania Faculty : History Author : Suchait Kahlon Award : 2021 Hilary Conroy Prize for Best Honors Thesis in World History Title : “Abolition, Africans, and Abstraction: the Influence of the “Noble Savage” on British and French Antislavery Thought, 1787-1807”

University : Columbia University Faculty : History Author : Julien Saint Reiman Award : 2018 Charles A. Beard Senior Thesis Prize Title : “A Starving Man Helping Another Starving Man”: UNRRA, India, and the Genesis of Global Relief, 1943-1947

University: University College London Faculty: Geography Author: Anna Knowles-Smith Award: 2017 Royal Geographical Society Undergraduate Dissertation Prize Title: Refugees and theatre: an exploration of the basis of self-representation

University: University of Washington Faculty: Computer Science & Engineering Author: Nick J. Martindell Award: 2014 Best Senior Thesis Award Title: DCDN: Distributed content delivery for the modern web

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

University: University of Edinburgh Faculty: Informatics Author: Christopher Sipola Award: 2018 Social Responsibility & Sustainability Dissertation Prize Title: Summarizing electricity usage with a neural network

University: University of Ottawa Faculty: Education Author: Matthew Brillinger Award: 2017 Commission on Graduate Studies in the Humanities Prize Title: Educational Park Planning in Berkeley, California, 1965-1968

University: University of Ottawa Faculty: Social Sciences Author: Heather Martin Award: 2015 Joseph De Koninck Prize Title: An Analysis of Sexual Assault Support Services for Women who have a Developmental Disability

University : University of Ottawa Faculty : Physics Author : Guillaume Thekkadath Award : 2017 Commission on Graduate Studies in the Sciences Prize Title : Joint measurements of complementary properties of quantum systems

University: London School of Economics Faculty: International Development Author: Lajos Kossuth Award: 2016 Winner of the Prize for Best Overall Performance Title: Shiny Happy People: A study of the effects income relative to a reference group exerts on life satisfaction

University : Stanford University Faculty : English Author : Nathan Wainstein Award : 2021 Alden Prize Title : “Unformed Art: Bad Writing in the Modernist Novel”

University : University of Massachusetts at Amherst Faculty : Molecular and Cellular Biology Author : Nils Pilotte Award : 2021 Byron Prize for Best Ph.D. Dissertation Title : “Improved Molecular Diagnostics for Soil-Transmitted Molecular Diagnostics for Soil-Transmitted Helminths”

University: Utrecht University Faculty: Linguistics Author: Hans Rutger Bosker Award: 2014 AVT/Anéla Dissertation Prize Title: The processing and evaluation of fluency in native and non-native speech

University: California Institute of Technology Faculty: Physics Author: Michael P. Mendenhall Award: 2015 Dissertation Award in Nuclear Physics Title: Measurement of the neutron beta decay asymmetry using ultracold neutrons

University: Stanford University Faculty: Management Science and Engineering Author: Shayan O. Gharan Award: Doctoral Dissertation Award 2013 Title: New Rounding Techniques for the Design and Analysis of Approximation Algorithms

University: University of Minnesota Faculty: Chemical Engineering Author: Eric A. Vandre Award: 2014 Andreas Acrivos Dissertation Award in Fluid Dynamics Title: Onset of Dynamics Wetting Failure: The Mechanics of High-speed Fluid Displacement

University: Erasmus University Rotterdam Faculty: Marketing Author: Ezgi Akpinar Award: McKinsey Marketing Dissertation Award 2014 Title: Consumer Information Sharing: Understanding Psychological Drivers of Social Transmission

University: University of Washington Faculty: Computer Science & Engineering Author: Keith N. Snavely Award: 2009 Doctoral Dissertation Award Title: Scene Reconstruction and Visualization from Internet Photo Collections

University: University of Ottawa Faculty: Social Work Author: Susannah Taylor Award: 2018 Joseph De Koninck Prize Title: Effacing and Obscuring Autonomy: the Effects of Structural Violence on the Transition to Adulthood of Street Involved Youth

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

George, T. (2023, April 06). Prize-Winning Thesis and Dissertation Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 27 September 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/prize-winning-dissertations/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, how to choose a dissertation topic | 8 steps to follow, how to write a thesis or dissertation conclusion, dissertation & thesis outline | example & free templates.

- Faculty Intranet

DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS

- Degree Requirements & Goals

- Goals for Second and Third Year Graduate Students

Dissertation Prospectus

The prospectus signifies two things. The first is that the student has an acceptable thesis proposal, which is defended at an oral examination. The second is completion of all coursework which comprises the field course requirements including the history requirement, and two Economics 501 presentations.

The oral examination ascertains whether the student's dissertation topic is feasible. The student selects a prospective thesis advisor and a committee of examiners. The student works with the advisor and committee to write a thesis proposal, which is the basis of the oral examination. It is important that the student choose a thesis advisor several months before the proposed oral examination. The advisor's assistance is invaluable in developing a thesis topic.

The terms “advisor” and “committee chair” are used interchangeably.

Read some advice on committee formation .

Committee Composition

Rules on the composition of the committee are:

- The committee must have three or more individuals.

- At least two members of this committee, including the chair, must be members of the Northwestern University Graduate Faculty.

- The chair of the committee must hold a tenure-line appointment in the Economics Department or have a voted courtesy appointment in the Economics Department.

- If the committee chair holds a courtesy appointment, at least one other member of the committee must hold a tenure-line appointment in the Economics Department.

Exceptions to conditions 3 and 4 are only permissible with prior written approval of the Director of Graduate Studies. Faculty outside Economics holding courtesy appointments are:

- Dranove, David

- Guryan, Jonathan

- Hartline, Jason

- Hubbard, Thomas

- Jones, Benjamin

- Karlan, Dean

- Molavi, Pooya

- Persico, Nicola

- Qian, Nancy

- Rebelo, Sergio

- Schanzenbach, Diane

- Schwandt, Hannes

Time Limits

The department expects that students making good progress should have completed their coursework and successfully defended their dissertation prospectus by August 31 at the end of their third year. This is a requirement for fourth year funding.

If a student has not completed their coursework and successfully defended their dissertation prospectus by the end of the Fall Quarter in their fourth year of study, which falls on the last date of the 13th quarter of study, they are placed on departmental probation. A student who fails to resume satisfactory academic standing within two quarters, which is the last date of the Spring Quarter in their fourth year of study (last date of the 15th quarter of study) is excluded from the program and Northwestern University.

Administrative Procedures

After completing all course work, and scheduled the oral qualifying examination, initiate the process by submitting the Prospectus Committee form to TGS on-line using GSTS . Select the "TGS Forms" tab, and then select the prospectus from the pull-down menu.

TGS then asks the department to verify that the course work is complete, and a successful prospectus defense occurred. So that the department can do this, the candidate should complete the department's Certification of a Dissertation Prospectus form.

Complete sections 1 to 3 of this form before the oral examination. These sections ask for information on course work. Take the form to the oral examination, where committee members can sign their acceptance of the prospectus in section 4.

The completed form, along with a transcript (which can be downloaded from CAESAR), should be returned immediately to the Graduate Program Manager’s office. The Director of Graduate Studies reviews the form and authorizes TGS to accept the prospectus.

A Note on Human Subjects