- DSpace@MIT Home

- MIT Libraries

- Graduate Theses

ChatGPT and the Future of Management Consulting: Opportunities and Challenges Ahead

Terms of use

Date issued, collections.

Suggestions or feedback?

MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Machine learning

- Sustainability

- Black holes

- Classes and programs

Departments

- Aeronautics and Astronautics

- Brain and Cognitive Sciences

- Architecture

- Political Science

- Mechanical Engineering

Centers, Labs, & Programs

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL)

- Picower Institute for Learning and Memory

- Lincoln Laboratory

- School of Architecture + Planning

- School of Engineering

- School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

- Sloan School of Management

- School of Science

- MIT Schwarzman College of Computing

Study finds ChatGPT boosts worker productivity for some writing tasks

Press contact :, media download.

*Terms of Use:

Images for download on the MIT News office website are made available to non-commercial entities, press and the general public under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives license . You may not alter the images provided, other than to crop them to size. A credit line must be used when reproducing images; if one is not provided below, credit the images to "MIT."

Previous image Next image

Amid a huge amount of hype around generative AI, a new study from researchers at MIT sheds light on the technology’s impact on work, finding that it increased productivity for workers assigned tasks like writing cover letters, delicate emails, and cost-benefit analyses.

The tasks in the study weren’t quite replicas of real work: They didn’t require precise factual accuracy or context about things like a company’s goals or a customer’s preferences. Still, a number of the study’s participants said the assignments were similar to things they’d written in their real jobs — and the benefits were substantial. Access to the assistive chatbot ChatGPT decreased the time it took workers to complete the tasks by 40 percent, and output quality, as measured by independent evaluators, rose by 18 percent.

The researchers hope the study , which appears today in open-access form in the journal Science , helps people understand the impact that AI tools like ChatGPT can have on the workforce.

“ What we can say for sure is generative AI is going to have a big effect on white collar work,” says Shakked Noy, a PhD student in MIT’s Department of Economics, who co-authored the paper with fellow PhD student Whitney Zhang ’21. “I think what our study shows is that this kind of technology has important applications in white collar work. It’s a useful technology. But it’s still too early to tell if it will be good or bad, or how exactly it’s going to cause society to adjust.”

Simulating work for chatbots

For centuries, people have worried that new technological advancements would lead to mass automation and job loss. But new technologies also create new jobs, and when they increase worker productivity, they can have a net positive effect on the economy.

“Productivity is front of mind for economists when thinking of new technological developments,” Noy says. “The classical view in economics is that the most important thing that technological advancement does is raise productivity, in the sense of letting us produce economic output more efficiently.”

To study generative AI’s effect on worker productivity, the researchers gave 453 college-educated marketers, grant writers, consultants, data analysts, human resource professionals, and managers two writing tasks specific to their occupation. The 20- to 30-minute tasks included writing cover letters for grant applications, emails about organizational restructuring, and plans for analyses helping a company decide which customers to send push notifications to based on given customer data. Experienced professionals in the same occupations as each participant evaluated each submission as if they were encountering it in a work setting. Evaluators did not know which submissions were created with the help of ChatGPT.

Half of participants were given access to the chatbot ChatGPT-3.5, developed by the company OpenAI, for the second assignment. Those users finished tasks 11 minutes faster than the control group, while their average quality evaluations increased by 18 percent.

The data also showed that performance inequality between workers decreased, meaning workers who received a lower grade in the first task benefitted more from using ChatGPT for the second task.

The researchers say the tasks were broadly representative of assignments such professionals see in their real jobs, but they noted a number of limitations. Because they were using anonymous participants, the researchers couldn’t require contextual knowledge about a specific company or customer. They also had to give explicit instructions for each assignment, whereas real-world tasks may be more open-ended. Additionally, the researchers didn’t think it was feasible to hire fact-checkers to evaluate the accuracy of the outputs. Accuracy is a major problem for today’s generative AI technologies.

The researchers said those limitations could lessen ChatGPT’s productivity-boosting potential in the real world. Still, they believe the results show the technology’s promise — an idea supported by another of the study’s findings: Workers exposed to ChatGPT during the experiment were twice as likely to report using it in their real job two weeks after the experiment.

“The experiment demonstrates that it does bring significant speed benefits, even if those speed benefits are lesser in the real world because you need to spend time fact-checking and writing the prompts,” Noy says.

Taking the macro view

The study offered a close-up look at the impact that tools like ChatGPT can have on certain writing tasks. But extrapolating that impact out to understand generative AI’s effect on the economy is more difficult. That’s what the researchers hope to work on next.

“There are so many other factors that are going to affect wages, employment, and shifts across sectors that would require pieces of evidence that aren’t in our paper,” Zhang says. “But the magnitude of time saved and quality increases are very large in our paper, so it does seem like this is pretty revolutionary, at least for certain types of work.”

Both researchers agree that, even if it’s accepted that ChatGPT will increase many workers’ productivity, much work remains to be done to figure out how society should respond to generative AI’s proliferation.

“The policy needed to adjust to these technologies can be very different depending on what future research finds,” Zhang says. “If we think this will boost wages for lower-paid workers, that’s a very different implication than if it’s going to increase wage inequality by boosting the wages of already high earners. I think there’s a lot of downstream economic and political effects that are important to pin down.”

The study was supported by an Emergent Ventures grant, the Mercatus Center, George Mason University, a George and Obie Shultz Fund grant, the MIT Department of Economics, and a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Grant.

Share this news article on:

Press mentions.

The Hill reporter Tobias Burns spotlights the efforts of a number of MIT researchers to better understand the impact of generative AI on productivity in the workforce. One research study “looked as cases where AI helped improved productivity and worker experience specifically in outsourced settings, such as call centers,” explains Burns. Another research study explored the impact of AI programs, such as ChatGPT, among employees.

Researchers from MIT have found that using generative AI chatbots can improve the speed and quality of simple writing tasks, but often lack factual accuracy, reports Richard Nieva for Forbes . “When we first started playing with ChatGPT, it was clear that it was a new breakthrough unlike anything we've seen before,” says graduate student Shakked Noy. “And it was pretty clear that it was going to have some kind of labor market impact.”

Previous item Next item

Related Links

- Department of Economics

Related Topics

- Graduate, postdoctoral

- Artificial intelligence

- Human-computer interaction

- Technology and society

- School of Humanities Arts and Social Sciences

- Labor and jobs

Related Articles

Researchers teach an AI to write better chart captions

If art is how we express our humanity, where does AI fit in?

3 Questions: Jacob Andreas on large language models

More mit news.

A faster, better way to train general-purpose robots

Read full story →

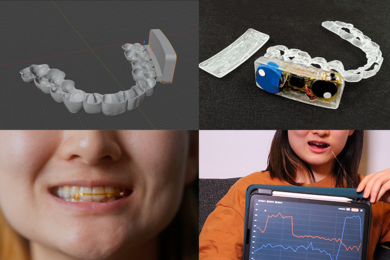

Interactive mouthpiece opens new opportunities for health data, assistive technology, and hands-free interactions

Study: Hospice care provides major Medicare savings

Scientists discover molecules that store much of the carbon in space

Study: Fusion energy could play a major role in the global response to climate change

SMART researchers develop a method to enhance effectiveness of cartilage repair therapy

- More news on MIT News homepage →

Massachusetts Institute of Technology 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA, USA

- Map (opens in new window)

- Events (opens in new window)

- People (opens in new window)

- Careers (opens in new window)

- Accessibility

- Social Media Hub

- MIT on Facebook

- MIT on YouTube

- MIT on Instagram

- Mailing List

- Search Search

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

Advice and responses from faculty on ChatGPT and A.I.-assisted writing

Because instructors at MIT and elsewhere have expressed some urgency in better understanding what the effects and ethics of ChatGPT may be, two pairs of our faculty have provided an advisory memo and a response.

Several faculty members in CMS/W have expertise, both technological and pedagogical, in what the use of ChatGPT and other A.I. tools may mean for the instruction of academic writing. Because instructors at MIT and elsewhere have expressed some urgency in better understanding what the effects and ethics of ChatGPT may be, two pairs of our faculty have provided an advisory memo and a response.

It should be noted that with tools like ChatGPT being both so new and so quickly evolving, these pieces are the faculty’s take and don’t yet represent official guidance from CMS/W or MIT.

First is an excerpt from “Advice Concerning the Increase in AI-Assisted Writing” , a memo from Edward Schiappa , Professor of Rhetoric, and Nick Montfort , Professor of Digital Media. The full document is available at Montfort’s website . (January 26 update: Professor Montfort discussed this topic with NPR’s All Things Considered .)

It may be that the use of a system like ChatGPT is not only acceptable to you but is integrated into the subject, and should be required. One of us taught a course dealing with digital media and writing last semester in which students were assigned to computer-generate a paper using such a freely-available LLM. Students were also assigned to reflect on their experience afterwards, briefly, in their own writing. The group discussed its process and insights in class, learning about the abilities and limitations of these models. The assignment also prompted students to think about human writing in new ways. There are, however, reasons to question the practice of AI and LLM text generation in college writing courses. First, if the use of such systems is not agreed upon and acknowledged, the practice is analogous to plagiarism. Students will be presenting writing as their own that they did not produce. To be sure, there are practices of ghost writing and of appropriation writing (including parody) which, despite their similarity to plagiarism, are considered acceptable in particular contexts. But in an educational context, when writing of this sort is not authorized or acknowledged, it does not advance learning goals and makes the evaluation of student achievement difficult or impossible. Second, and relatedly, current AI and LLM technologies provide assistance that is opaque. Even a grammar checker will explain the grammatical principle that is being violated. A writing instructor should offer much better explanatory help to a student. But current AI systems just provide a continuation of a prompt. Third, the Institute’s Communication Requirement was created (in part) in response to alumni reporting that writing and speaking skills were essential for their professional success, and that they did not feel their undergraduate education adequately prepared them to be effective communicators.[1] It may be, in the fullness of time, that learning how to use AI/LLM technologies to assist writing will be an important or even essential skill. But we are not at this juncture yet, and the core rhetorical skills involving in written and oral communication—invention, style, grammar, reasoning and argument construction, and research—are ones every MIT undergraduate still needs to learn.

And next is a response co-authored by Professor Eric Klopfer , head of CMS/W and Literature and director of the Scheller Teacher Education Program , and Associate Professor Justin Reich , director of the Teaching Systems Lab .

“Calculating the Future of Writing in the Face of AI”

When the AI text generation platform ChatGPT was released, it made a lot of people take notice of the potential impact of the coming wave of Large Language Models (and even proclaim the end of the college essay ). The uproar over ChatGPT prompted mathematics educators to declare, “Ha, writing people, now it’s your turn!” Or, as math teacher Michael Pershan framed the issue, in an effort to capture the mood of ChatGPT headline writers, “I FED CASIO-FX1239x MY MATH TEST AND WAS ASTONISHED BY THE RESULTS.”

There now exists a computing device which, when given open-ended queries similar to those typically offered by instructors, responds instantly and automatically with a range of plausibly correct results. A reliance on this device could deprive students of the opportunities to develop for themselves the foundational skills necessary for the human resolution of said queries. Or it could usher in a new era of human inquiry and expression assisted by technology. Or both. The humble calculator has been the perfect rehearsal for the challenges we face today.

As calculators became cheap and ubiquitous, they threatened the teaching of rote mathematics ( Per Urlaub and Eva Dessein draw a similar comparison to the related issue of automated language translation). At that inflection point, teachers typically pursued any of three choices: 1) they could allow calculators and risk trivializing existing learning experiences, 2) ban calculators in the hopes of preserving the pre-Casio status quo, or 3) adapt and create some learning environments where students could not use calculators (prominent today in the memorization of math facts like times tables) but in most places shift instruction to challenge students to think about what they need to enter into the calculators.

The first two tactics were largely unsuccessful, though they persist to some extent. Our challenge is to figure out where to preserve the best of older habits, while shifting to embrace new technologies for how, like calculators, they can augment human capacity in our disciplines.

Writing instructors already have much experience with these challenges. Spellcheck software was banned in many classrooms because of its potential negative effects on student spelling. Today, a student who didn’t spellcheck their paper is labeled as careless. Wikipedia, research sources on the internet, and automated translation services (for our colleagues teaching writing in second languages) have all bedeviled writing instructors in recent years.

We should be cautious about technological determinism; we should be cautious about the creeping belief that we simply have to accept and adapt to ChatGPT. Maybe ChatGPT is terrible in ways we don’t yet understand, and bans will prove to be a viable and important option. But the history of these recent aids to human cognitive and communication suggests that they are pretty helpful; the best of their contributions can be integrated into our writing practices, and the worst of their shortcuts can be mitigated by walling them off from targeted areas of our curriculum–by teaching bits and pieces here and there where ChatGPT and future tools are banned, like calculators are banned when students memorize math facts. If ChatGPT proves to be an outlier from this historical trend, by all means let’s ban it, but until then let’s proceed cautiously but open to possibilities. The proclamations of the end of the essay have come alongside both popular press such as in The New York Times and TIME and scholarly work (such as “New Modes of Learning Enabled by AI Chatbots: Three Methods and Assignments” by Ethan R. Mollick and Lilach Mollick) with a more hopeful outlook – one that both sees short term benefits and positive long term shifts.

In terms of practical advice for instructors who rely on written papers as a form of assessment, the most important advice is to try some of these tools out yourself to see what they can and cannot do. After doing so you may decide that as they stand now, you should prohibit their use entirely. But you might instead choose to limit use to certain cases that would need to be documented. For example, you might allow students to generate ideas for an initial draft but not allow any prose generated by the models. There are several ways in which these tools could be used right away:

- They can be used to help struggling writers who don’t know where to begin with their assignments.

- They can be used as a thought partner by students as they bounce around ideas that can be further developed.

- They can help students revise their ideas through reframing or restating their prose.

The presence of disruptive technologies like ChatGPT should cause us to reflect on our learning goals, outcomes, and assessments, and determine whether we should change them in response, wall off the technology, or change the technology itself to better support our intended outcomes. We should not let our existing approaches remain simply because this is the way we have always done them. We should also not ruin what is great about writing in the name of preventing cheating. We could make students hand-write papers in class and lose the opportunity to think creatively and edit for clarity. Instead, we should double down on our goal of making sure that students become effective written and oral communicators both here at MIT and beyond. For better or worse, these technologies are part of the future of our world. We need to teach our students if it is appropriate to use them, and, if so, how and when to work alongside them effectively.

In the 19th century, a group of secondary school educators believed urgently and fervently that sentence diagramming was an essential part of writing education. They fought tooth and nail in education journals, meetings, and curriculum materials to preserve their beloved practice. They were wrong. We’re fine without them. Maybe we will be fine without the short answer questions that call for the recounting of factual information, the sorts of homework questions where ChatGPT currently seems to do pretty well (though, just like our students, it sometimes makes up incorrect but plausible-sounding responses).

Assuredly, we will need to think deeply about the new affordances of ChatGPT, and the kinds of thinking and writing we want students to do in the age of AI and change our teaching and assessment to serve them better. We will have to have the kinds of conversations and negotiations with students that we had upon the arrival of Wikipedia, other Internet research sources, grammar and spell checkers, and other aids to research and writing. They took up a good bit of class time upon their arrival, and then we settled into more efficient and productive stances.

We will also need to think about whether these technologies cause us to define new outcomes and skills that we will need to find new ways to teach. At MIT, an institution which is at the forefront of AI and one that prides itself in both its teaching in the humanities and consideration of the human implications of technology, we should lead the way in studying and defining this path forward.

Ultimately, Michael Pershan from his math classroom sends us writing teachers his good wishes: “If the lives of math teachers — who have a head start on this calculator business — are any example, it’ll change things slightly and give everyone something fun to fight about.” We look forward to the ensuing debates.

Related articles

Landman Report Card highlighted in Good Clean Tech, PC Magazine

Colloquium Examines Podcasting, Television’s Future

Podcast: “gaming the iron curtain”.

Anthropologist Stefan Helmreich studies researchers studying ocean microbes

ChatGPT, Graduate School, & Me

By eliza price, a grad student’s guide to ai in research and science communication..

The rise of ChatGPT and other AI tools has forced educators to respond with updated teaching and assessment strategies at MIT and across the globe [1, 2, 3]. As a graduate student and AI novice, my response to these tools was more curiosity than panic. These new tools seem to promise more efficient paper drafting, literature searches, and problem-solving, but the more time I spent querying ChatGPT, the less confident I felt in determining how and if AI should have a place in my research workflow. So, I set out to learn about these tools, understand their limitations, and test them for several research tasks.

Here I’ll share my journey and zoom in on the two tools I found to be most useful, ChatGPT and Elicit. Like any dutiful researcher considering a new experiment, I will focus on the key questions: Is this effective? and is this ethical? Whether you are an AI novice like me or keep a dedicated browser open for ChatGPT, I encourage you to join me in wrestling with these questions as you consider how to use AI tools responsibly in your research.

Is this effective?

ChatGPT is a language processing tool powered by a machine-learning-based large language model (LLM). In other words, ChatGPT creates human-sounding responses to the prompts posed to it by essentially performing language regression, predicting which words are most likely to be associated with each other [4]. In practice, this means that ChatGPT can write a grammatically coherent essay, but through the quirks of probability, it might hallucinate the facts that make up the content.

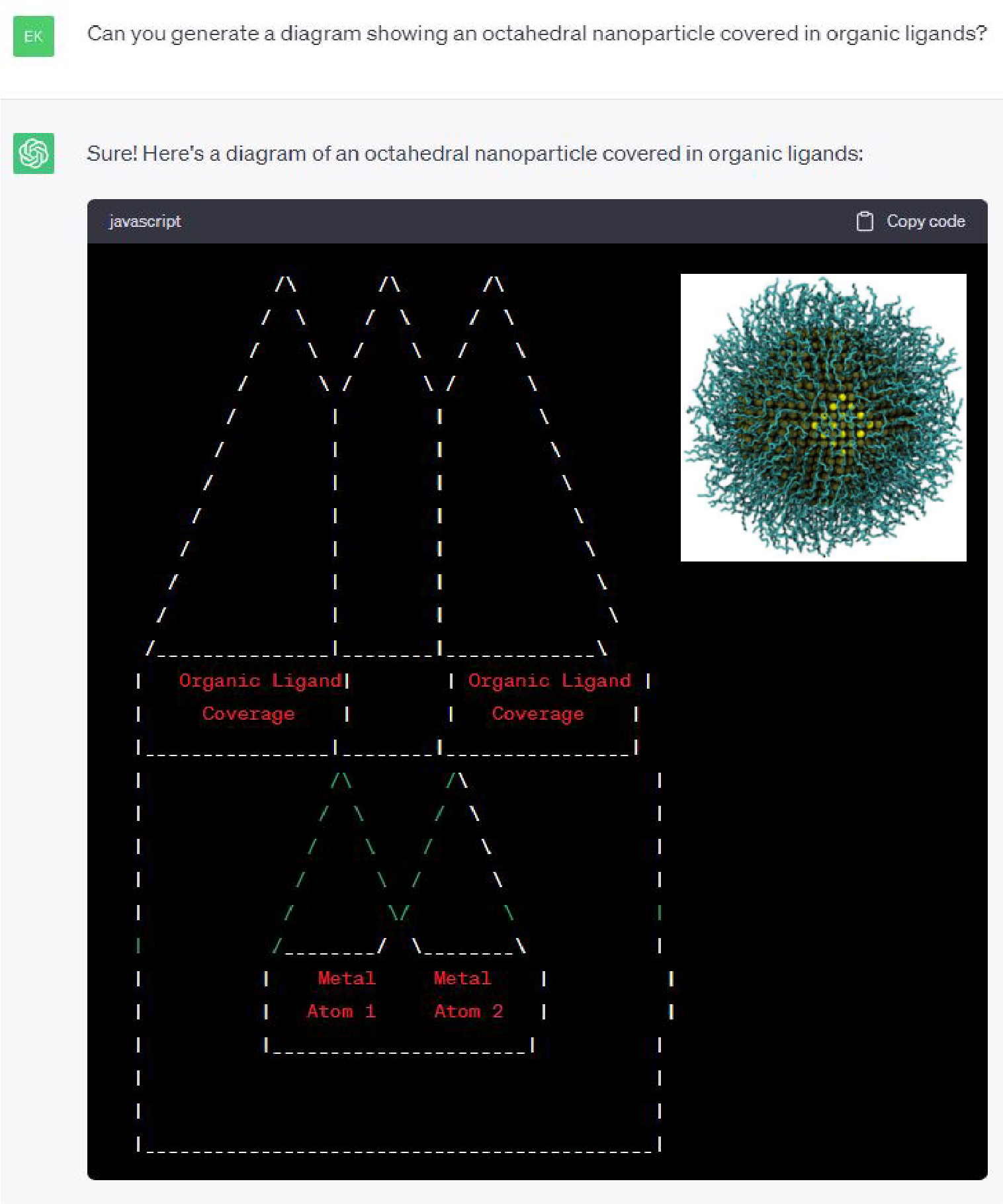

This hallucination appeared early on in my experimentation with ChatGPT. When I asked how ChatGPT can help me communicate science, one suggestion it gave was generating “visual aids such as graphs, diagrams, and infographics.” A follow-up query asking for a visual aid related to my research resulted in the JavaScript beauty shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. ChatGPT claimed that it could generate scientific diagrams. The main figure shows its take on a nanoparticle covered in ligands. The inset (top right) shows a published figure for reference. [5]

Although I certainly won’t be using ChatGPT to make figures anytime soon, I found it much more effective for other research tasks. Table 1 summarizes my experience using ChatGPT to brainstorm analogies, simplify language, write an email, translate code, and write a paper introduction.

Table 1. Summary of ChatGPT’s strengths and weaknesses for various research tasks

My early experimentation showed that ChatGPT cannot be trusted to give factual information, even about its own capabilities. Instead, I found that ChatGPT performs best on tasks where you provide the content up front or heavily revise the AI response. In my opinion, ChatGPT is most effective as a tool for writing synthesis and organization, but however you choose to use ChatGPT, the key is validation. Any claim that you want to make in a piece of writing should come from you.

Elicit is an “AI research assistant” with the primary functions of literature review and brainstorming research questions. It interprets and summarizes scientific literature using LLMs, including GPT-3, but unlike ChatGPT, Elicit is customized to stay true to the content in papers. Even still, the company FAQs estimate its accuracy as 80-90% [6].

Since Elicit is a more targeted tool than ChatGPT, using it effectively requires an organized workflow. My typical method to perform a literature search with Elicit is

- Ask a research question.

- Star relevant papers and hone results with the “show more like starred” option.

- Customize paper information beyond the default “paper title” and “abstract summary” options. My favorite headings to add were “main findings” and “outcomes measured.”

- Export search results as a CSV file.

Table 2 shows a summary of my experiments using Elicit to perform a literature review and explain my paper .

Table 2. Summary of Elicit’s strengths and weaknesses for various research tasks

Unlike ChatGPT, most information that Elicit serves up is true to the cited sources. However, its results still need validation since the information it pulls can be incomplete or misinterpreted. For this reason, I am most comfortable using Elicit as an initial screening tool, and I definitely recommend reading the papers before citing them in your own work.

Is this ethical?

There is no easy answer to the question of the ethics of AI, as evidenced by the tons of academic papers and op-eds already published on the topic [7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12]. In my own thinking about AI and scientific research, the ethical facets which stood out to me the most are privacy, plagiarism, bias, and accountability.

Privacy and plagiarism

Did you know that the prompts you enter in ChatGPT are fair game to use in training the LLM? Even though OpenAI now provides a form allowing you to opt out of model training, many have flagged this as a serious privacy issue [13].

Imagine using ChatGPT to revise an initial paper draft. Should you worry that parts of your unpublished work may be served up to another user who asks about the same topic? On the other hand, imagine you ask ChatGPT to write part of your paper and, in doing so, unknowingly plagiarize other papers in the field.

The root issue of both scenarios is a lack of transparency in the LLM powering ChatGPT. Unlike emerging open-source language models, OpenAI does not provide public access to the GPT training data [14]. Yet even if it did, understanding the origin of model-generated content is not straightforward. If ChatGPT trains on your unpublished paper, that simply translates to a change in the numeric parameters of the LLM producing its responses. According to OpenAI, the model does not actually “store or copy the sentences that it read[s].” [4]

This seems to make explicit plagiarism less likely, but when it comes to the inner workings of these models, there is a lot we as users don’t know. Is it still possible for ChatGPT to plagiarize its training sources through a coincidence of its algorithm? Does this become more likely when you are in a niche field with less training data, such as a research topic for a Ph.D. thesis?

Bias in many forms

If you peel back the layers of ChatGPT, you’ll find a hierarchy of well-documented bias [15, 16]. As a researcher, the categories I worry about the most are sample, automation, and authority bias.

Sample bias is inherited from the counterfactual, harmful, or limited content in the training data of LLMs (e.g. the internet). For research applications, sample bias is most apparent in ChatGPT’s limited knowledge of the research literature. For example, when asked to summarize the work of several researchers, ChatGPT was only able to give accounts for some scientists, failing to produce any information about even highly renowned researchers [7]. Elicit may do a better job of this, but its content is still limited to the Semantic Scholar Academic Graph dataset [6, 17].

On the other hand, automation bias comes from how we choose to use AI tools and, specifically, when we over-rely on automation. Completely removing the human element from our research workflows can result in a worse outcome. Relying too much on automated AI tools for research tasks might lead us to reference hallucinated citations from ChatGPT, skip over key literature missing from Elicit’s dataset, or forgo human creativity in communication in favor of ChatGPT’s accessible but formulaic prose.

A closely related concept is authority bias , when we cede intellectual authority to AI, even against our best interests and intuition. Both my experiments and others highlight the weak points of AI’s knowledge and capabilities. As it stands today, AI isn’t actually that smart and does not deserve our intellectual deference [18].

These layers of bias highlight the need for clear guidelines on personal and professional accountability when using AI tools in research and scientific communication.

Accountability

In response to the growing use of AI tools, many journals have released statements on how AI may be used for drafting papers. The Nature guidelines are: 1) ChatGPT cannot be listed as an author on a paper and 2) how and if you use ChatGPT should be documented in the methods or acknowledgment sections of your paper [19]. Ultimately, you and the other human authors bear the full weight of accountability for the content of your paper.

In my opinion, both the weight of accountability and the inherent black-box nature of ChatGPT should make us cautious about how we use AI in scientific communication. The best way to protect against plagiarized, biased, and hallucinated content is to avoid relying on AI for content generation.

How do we move forward?

So what is an effective, ethical way to use AI to help with research tasks? Personally, I err on the side of caution, limiting my use of ChatGPT to the synthesis and revision of human-provided content and my use of Elicit to the beginning stages of a literature review. My methods aren’t right for everyone, though. How you choose to use AI should be determined by your ethical compass as well as the guidelines of your PI and research community.

No matter your comfort level, the best advice I can give for using AI tools in your research is to be transparent in how you use AI and validate AI content wherever possible . Ultimately, the best way to build AI into your research workflow is to experiment with it yourself, keeping in mind these core questions of effectiveness and ethics as you go.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to EECS Communication Lab Manager, Deanna Montgomery for sharing her framework on evaluating ethics and efficacy in AI.

[1] K. Huang, “Alarmed by A.I. Chatbots, Universities Start Revamping How They Teach,” The New York Times, 16 January 2023. [Online].

[2] D. Nocivelli, “Teaching & Learning with ChatGPT: Opportunity or Quagmire? Part I,” MIT Teaching + Learning Lab, 12 January 2023. [Online].

[3] D. Bruff, “Teaching in the Artificial Intelligence Age of ChatGPT,” MIT Teaching + Learning Lab, 22 March 2023. [Online].

[4] Y. Markovski, “How ChatGPT and Our Language Models Are Developed,” OpenAI, [Online]. Available: https://help.openai.com/en/articles/7842364-how-chatgpt-and-our-language-models-are-developed#h_93286961be . [Accessed 7 June 2023].

[5] S. W. Winslow, W. A. Tisdale and J. W. Swan, “Prediction of PbS Nanocrystal Superlattice Structure with Large-Scale Patchy Particle Simulations,” The Journal of Physical Chemistry C , vol. 126, pp. 14264-14274, 2022.

[6] “Frequently Asked Questions,” Elicit, [Online]. Available: https://elicit.org/faq#what-are-the-limitations-of-elicit . [Accessed 7 June 2023].

[7] E. A. M. v. Dis, J. Bollen, W. Zuidema, R. v. Rooij and C. L. Bockting, “ChatGPT: five priorities for research,” Nature , 3 February 2023. [Online].

[8] E. L. Hill-Yardin, M. R. Hutchinson, R. Laycock and S. J. Spencer, “A Chat(GPT) about the future of scientific publishing,” Brain, Behavior, and Immunity , vol. 110, pp. 152-154, 2023.

[9] D. O. Eke, “ChatGPT and the rise of generative AI: Threat to academic integrity?,” Journal of Responsible Technology , vol. 13, p. 100060, 2023.

[10] B. Lung, T. Wang, N. R. Mannuru, B. Nie, S. Shimray and Z. Wang, “ChatGPT and a new academic reality: Artificial Intelligence-written research papers and the ethics of the large language models in scholarly publishing,” Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology , vol. 74, no. 5, pp. 570-581, 2023.

[11] R. Gruetzemacher, “The Power of Natural Language Processing,” Harvard Business Review, 19 April 2022. [Online]. Available: https://hbr.org/2022/04/the-power-of-natural-language-processing .

[12] M. Hutson, “Could AI help you to write your next paper?,” Nature , 31 October 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-03479-w .

[13] “User Content Opt Out Request,” OpenAI, [Online]. Available: https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLScrnC-_A7JFs4LbIuzevQ_78hVERlNqqCPCt3d8XqnKOfdRdQ/viewform . [Accessed 7 June 2023].

[14] E. Gibney, “Open-source language AI challenges big tech’s models,” Nature , 22 June 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-01705-z .

[15] B. Cousins, “Uncovering The Different Types of ChatGPT Bias,” Forbes, 31 March 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2023/03/31/uncovering-the-different-types-of-chatgpt-bias/?sh=4dcf52fc571b .

[16] H. Getahun, “ChatGPT could be used for good, but like many other AI models, it’s rife with racist and discriminatory bias,” Insider, 16 January 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.insider.com/chatgpt-is-like-many-other-ai-models-rife-with-bias-2023-1 .

[17] “Semantic Scholar API – Overview,” Semantic Scholar, [Online]. Available: https://www.semanticscholar.org/product/api . [Accessed 7 June 2023].

[18] I. Bogost, “ChatGPT Is Dumber Than You Think,” The Atlantic, 7 December 2022. [Online].

[19] “Tools such as ChatGPT threaten transparent science; here are our ground rules for their use,” Nature , 24 January 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-023-00191-1 .

Eliza Price is a graduate student in the Tisdale Lab and a ChemE Communication Fellow.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER COLUMN

- 08 April 2024

Three ways ChatGPT helps me in my academic writing

- Dritjon Gruda 0

Dritjon Gruda is an invited associate professor of organizational behavior at the Universidade Católica Portuguesa in Lisbon, the Católica Porto Business School and the Research Centre in Management and Economics.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Confession time: I use generative artificial intelligence (AI). Despite the debate over whether chatbots are positive or negative forces in academia, I use these tools almost daily to refine the phrasing in papers that I’ve written, and to seek an alternative assessment of work I’ve been asked to evaluate, as either a reviewer or an editor. AI even helped me to refine this article.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-01042-3

This is an article from the Nature Careers Community, a place for Nature readers to share their professional experiences and advice. Guest posts are encouraged .

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Related Articles

- Machine learning

- Peer review

From industry to stay-at-home father to non-profit leadership

Career Q&A 24 OCT 24

How I’m learning to navigate academia as someone with ADHD

Career Column 24 OCT 24

How to run a successful internship programme

Career Feature 23 OCT 24

Will AI’s huge energy demands spur a nuclear renaissance?

News Explainer 25 OCT 24

AI watermarking must be watertight to be effective

Editorial 23 OCT 24

AI-designed DNA sequences regulate cell-type-specific gene expression

News & Views 23 OCT 24

Exposing predatory journals: anonymous sleuthing account goes public

Nature Index 22 OCT 24

How to win a Nobel prize: what kind of scientist scoops medals?

News Feature 03 OCT 24

‘Substandard and unworthy’: why it’s time to banish bad-mannered reviews

Career Q&A 23 SEP 24

Assistant Professor of Molecular Genetics and Microbiology

The Department of Molecular Genetics and Microbiology at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine (http://mgm.unm.edu/index.html) is seeking...

University of New Mexico, Albuquerque

Assistant/Associate/Professor of Pediatrics (Neonatology)

Join the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Illinois College of Medicine Peoria as a full-time Neonatologist.

Peoria, Illinois

University of Illinois College of Medicine Peoria

Professor / Assistant Professor (Tenure Track) of Quantum Correlated Condensed and Synthetic Matter

The Department of Physics (www.phys.ethz.ch) at ETH Zurich invites applications for the above-mentioned position.

Zurich city

Associate or Senior Editor, Nature Communications (Structural Biology, Biochemistry, or Biophysics)

Job Title: Associate or Senior Editor, Nature Communications (Structural Biology, Biochemistry, or Biophysics) Locations: New York, Philadelphia, S...

New York City, New York (US)

Springer Nature Ltd

Faculty (Open Rank) - Bioengineering and Immunoengineering

The Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (PME) at the University of Chicago invites applications for multiple faculty positions (open rank) in ...

Chicago, Illinois

University of Chicago, Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

ChatGPT is essentially a probabilistic statistical model for generating texts that satisfy the statistical consistency with the hints, so the output may sometimes look logically correct but completely deviated from the facts in human's view.

This paper investigates the capabilities of ChatGPT as an automated assistant in diverse domains, including scientific writing, mathematics, education, programming, and healthcare. We explore the potential of ChatGPT to enhance productivity, streamline problem-solving processes, and improve writing style.

This thesis explores the implications of ChatGPT, a cutting-edge artificial intelligence (AI) language model, on the management consulting industry, focusing on opportunities and challenges it presents.

This illustrates a significant change in GPT-4’s behavior in responding (or not responding) to subjective questions. ChatGPT’s behavior shifts on sensitive and subjective queries impose several implications in practice.

ChatGPT is a powerful language model from OpenAI that is arguably able to comprehend and generate text. ChatGPT is expected to greatly impact society, research, and education.

Amid a huge amount of hype around generative AI, a new study from researchers at MIT sheds light on the technology’s impact on work, finding that it increased productivity for workers assigned tasks like writing cover letters, delicate emails, and cost-benefit analyses.

The presence of disruptive technologies like ChatGPT should cause us to reflect on our learning goals, outcomes, and assessments, and determine whether we should change them in response, wall off the technology, or change the technology itself to better support our intended outcomes.

ChatGPT is a language processing tool powered by a machine-learning-based large language model (LLM). In other words, ChatGPT creates human-sounding responses to the prompts posed to it by essentially performing language regression, predicting which words are most likely to be associated with each other [4].

ChatGPT is a large language model (LLM), a machine-learning system that autonomously learns from data and can produce sophisti-cated and seemingly intelligent writing after

ChatGPT has become indispensable in this process, helping me to craft precise, empathetic and actionable feedback without replacing human editorial decisions.