Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

Content Analysis | A Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Amy Luo . Revised on 5 December 2022.

Content analysis is a research method used to identify patterns in recorded communication. To conduct content analysis, you systematically collect data from a set of texts, which can be written, oral, or visual:

- Books, newspapers, and magazines

- Speeches and interviews

- Web content and social media posts

- Photographs and films

Content analysis can be both quantitative (focused on counting and measuring) and qualitative (focused on interpreting and understanding). In both types, you categorise or ‘code’ words, themes, and concepts within the texts and then analyse the results.

Table of contents

What is content analysis used for, advantages of content analysis, disadvantages of content analysis, how to conduct content analysis.

Researchers use content analysis to find out about the purposes, messages, and effects of communication content. They can also make inferences about the producers and audience of the texts they analyse.

Content analysis can be used to quantify the occurrence of certain words, phrases, subjects, or concepts in a set of historical or contemporary texts.

In addition, content analysis can be used to make qualitative inferences by analysing the meaning and semantic relationship of words and concepts.

Because content analysis can be applied to a broad range of texts, it is used in a variety of fields, including marketing, media studies, anthropology, cognitive science, psychology, and many social science disciplines. It has various possible goals:

- Finding correlations and patterns in how concepts are communicated

- Understanding the intentions of an individual, group, or institution

- Identifying propaganda and bias in communication

- Revealing differences in communication in different contexts

- Analysing the consequences of communication content, such as the flow of information or audience responses

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

- Unobtrusive data collection

You can analyse communication and social interaction without the direct involvement of participants, so your presence as a researcher doesn’t influence the results.

- Transparent and replicable

When done well, content analysis follows a systematic procedure that can easily be replicated by other researchers, yielding results with high reliability .

- Highly flexible

You can conduct content analysis at any time, in any location, and at low cost. All you need is access to the appropriate sources.

Focusing on words or phrases in isolation can sometimes be overly reductive, disregarding context, nuance, and ambiguous meanings.

Content analysis almost always involves some level of subjective interpretation, which can affect the reliability and validity of the results and conclusions.

- Time intensive

Manually coding large volumes of text is extremely time-consuming, and it can be difficult to automate effectively.

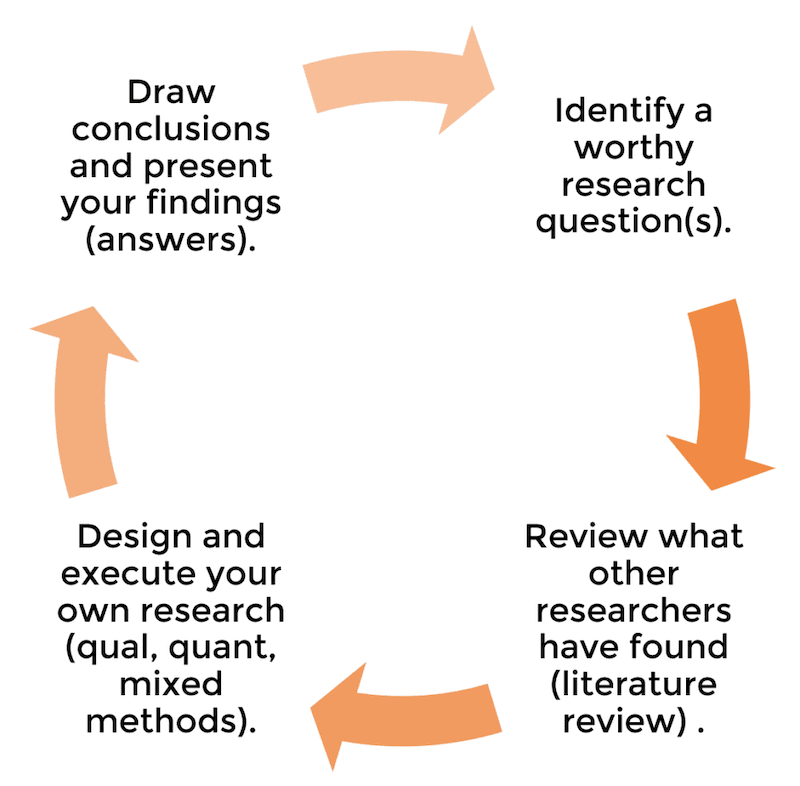

If you want to use content analysis in your research, you need to start with a clear, direct research question .

Next, you follow these five steps.

Step 1: Select the content you will analyse

Based on your research question, choose the texts that you will analyse. You need to decide:

- The medium (e.g., newspapers, speeches, or websites) and genre (e.g., opinion pieces, political campaign speeches, or marketing copy)

- The criteria for inclusion (e.g., newspaper articles that mention a particular event, speeches by a certain politician, or websites selling a specific type of product)

- The parameters in terms of date range, location, etc.

If there are only a small number of texts that meet your criteria, you might analyse all of them. If there is a large volume of texts, you can select a sample .

Step 2: Define the units and categories of analysis

Next, you need to determine the level at which you will analyse your chosen texts. This means defining:

- The unit(s) of meaning that will be coded. For example, are you going to record the frequency of individual words and phrases, the characteristics of people who produced or appear in the texts, the presence and positioning of images, or the treatment of themes and concepts?

- The set of categories that you will use for coding. Categories can be objective characteristics (e.g., aged 30–40, lawyer, parent) or more conceptual (e.g., trustworthy, corrupt, conservative, family-oriented).

Step 3: Develop a set of rules for coding

Coding involves organising the units of meaning into the previously defined categories. Especially with more conceptual categories, it’s important to clearly define the rules for what will and won’t be included to ensure that all texts are coded consistently.

Coding rules are especially important if multiple researchers are involved, but even if you’re coding all of the text by yourself, recording the rules makes your method more transparent and reliable.

Step 4: Code the text according to the rules

You go through each text and record all relevant data in the appropriate categories. This can be done manually or aided with computer programs, such as QSR NVivo , Atlas.ti , and Diction , which can help speed up the process of counting and categorising words and phrases.

Step 5: Analyse the results and draw conclusions

Once coding is complete, the collected data is examined to find patterns and draw conclusions in response to your research question. You might use statistical analysis to find correlations or trends, discuss your interpretations of what the results mean, and make inferences about the creators, context, and audience of the texts.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Luo, A. (2022, December 05). Content Analysis | A Step-by-Step Guide with Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 16 September 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/content-analysis-explained/

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked

How to do thematic analysis | guide & examples, data collection methods | step-by-step guide & examples, qualitative vs quantitative research | examples & methods.

Skip to content

Read the latest news stories about Mailman faculty, research, and events.

Departments

We integrate an innovative skills-based curriculum, research collaborations, and hands-on field experience to prepare students.

Learn more about our research centers, which focus on critical issues in public health.

Our Faculty

Meet the faculty of the Mailman School of Public Health.

Become a Student

Life and community, how to apply.

Learn how to apply to the Mailman School of Public Health.

Content Analysis

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Content analysis is a research tool used to determine the presence of certain words, themes, or concepts within some given qualitative data (i.e. text). Using content analysis, researchers can quantify and analyze the presence, meanings, and relationships of such certain words, themes, or concepts. As an example, researchers can evaluate language used within a news article to search for bias or partiality. Researchers can then make inferences about the messages within the texts, the writer(s), the audience, and even the culture and time of surrounding the text.

Description

Sources of data could be from interviews, open-ended questions, field research notes, conversations, or literally any occurrence of communicative language (such as books, essays, discussions, newspaper headlines, speeches, media, historical documents). A single study may analyze various forms of text in its analysis. To analyze the text using content analysis, the text must be coded, or broken down, into manageable code categories for analysis (i.e. “codes”). Once the text is coded into code categories, the codes can then be further categorized into “code categories” to summarize data even further.

Three different definitions of content analysis are provided below.

Definition 1: “Any technique for making inferences by systematically and objectively identifying special characteristics of messages.” (from Holsti, 1968)

Definition 2: “An interpretive and naturalistic approach. It is both observational and narrative in nature and relies less on the experimental elements normally associated with scientific research (reliability, validity, and generalizability) (from Ethnography, Observational Research, and Narrative Inquiry, 1994-2012).

Definition 3: “A research technique for the objective, systematic and quantitative description of the manifest content of communication.” (from Berelson, 1952)

Uses of Content Analysis

Identify the intentions, focus or communication trends of an individual, group or institution

Describe attitudinal and behavioral responses to communications

Determine the psychological or emotional state of persons or groups

Reveal international differences in communication content

Reveal patterns in communication content

Pre-test and improve an intervention or survey prior to launch

Analyze focus group interviews and open-ended questions to complement quantitative data

Types of Content Analysis

There are two general types of content analysis: conceptual analysis and relational analysis. Conceptual analysis determines the existence and frequency of concepts in a text. Relational analysis develops the conceptual analysis further by examining the relationships among concepts in a text. Each type of analysis may lead to different results, conclusions, interpretations and meanings.

Conceptual Analysis

Typically people think of conceptual analysis when they think of content analysis. In conceptual analysis, a concept is chosen for examination and the analysis involves quantifying and counting its presence. The main goal is to examine the occurrence of selected terms in the data. Terms may be explicit or implicit. Explicit terms are easy to identify. Coding of implicit terms is more complicated: you need to decide the level of implication and base judgments on subjectivity (an issue for reliability and validity). Therefore, coding of implicit terms involves using a dictionary or contextual translation rules or both.

To begin a conceptual content analysis, first identify the research question and choose a sample or samples for analysis. Next, the text must be coded into manageable content categories. This is basically a process of selective reduction. By reducing the text to categories, the researcher can focus on and code for specific words or patterns that inform the research question.

General steps for conducting a conceptual content analysis:

1. Decide the level of analysis: word, word sense, phrase, sentence, themes

2. Decide how many concepts to code for: develop a pre-defined or interactive set of categories or concepts. Decide either: A. to allow flexibility to add categories through the coding process, or B. to stick with the pre-defined set of categories.

Option A allows for the introduction and analysis of new and important material that could have significant implications to one’s research question.

Option B allows the researcher to stay focused and examine the data for specific concepts.

3. Decide whether to code for existence or frequency of a concept. The decision changes the coding process.

When coding for the existence of a concept, the researcher would count a concept only once if it appeared at least once in the data and no matter how many times it appeared.

When coding for the frequency of a concept, the researcher would count the number of times a concept appears in a text.

4. Decide on how you will distinguish among concepts:

Should text be coded exactly as they appear or coded as the same when they appear in different forms? For example, “dangerous” vs. “dangerousness”. The point here is to create coding rules so that these word segments are transparently categorized in a logical fashion. The rules could make all of these word segments fall into the same category, or perhaps the rules can be formulated so that the researcher can distinguish these word segments into separate codes.

What level of implication is to be allowed? Words that imply the concept or words that explicitly state the concept? For example, “dangerous” vs. “the person is scary” vs. “that person could cause harm to me”. These word segments may not merit separate categories, due the implicit meaning of “dangerous”.

5. Develop rules for coding your texts. After decisions of steps 1-4 are complete, a researcher can begin developing rules for translation of text into codes. This will keep the coding process organized and consistent. The researcher can code for exactly what he/she wants to code. Validity of the coding process is ensured when the researcher is consistent and coherent in their codes, meaning that they follow their translation rules. In content analysis, obeying by the translation rules is equivalent to validity.

6. Decide what to do with irrelevant information: should this be ignored (e.g. common English words like “the” and “and”), or used to reexamine the coding scheme in the case that it would add to the outcome of coding?

7. Code the text: This can be done by hand or by using software. By using software, researchers can input categories and have coding done automatically, quickly and efficiently, by the software program. When coding is done by hand, a researcher can recognize errors far more easily (e.g. typos, misspelling). If using computer coding, text could be cleaned of errors to include all available data. This decision of hand vs. computer coding is most relevant for implicit information where category preparation is essential for accurate coding.

8. Analyze your results: Draw conclusions and generalizations where possible. Determine what to do with irrelevant, unwanted, or unused text: reexamine, ignore, or reassess the coding scheme. Interpret results carefully as conceptual content analysis can only quantify the information. Typically, general trends and patterns can be identified.

Relational Analysis

Relational analysis begins like conceptual analysis, where a concept is chosen for examination. However, the analysis involves exploring the relationships between concepts. Individual concepts are viewed as having no inherent meaning and rather the meaning is a product of the relationships among concepts.

To begin a relational content analysis, first identify a research question and choose a sample or samples for analysis. The research question must be focused so the concept types are not open to interpretation and can be summarized. Next, select text for analysis. Select text for analysis carefully by balancing having enough information for a thorough analysis so results are not limited with having information that is too extensive so that the coding process becomes too arduous and heavy to supply meaningful and worthwhile results.

There are three subcategories of relational analysis to choose from prior to going on to the general steps.

Affect extraction: an emotional evaluation of concepts explicit in a text. A challenge to this method is that emotions can vary across time, populations, and space. However, it could be effective at capturing the emotional and psychological state of the speaker or writer of the text.

Proximity analysis: an evaluation of the co-occurrence of explicit concepts in the text. Text is defined as a string of words called a “window” that is scanned for the co-occurrence of concepts. The result is the creation of a “concept matrix”, or a group of interrelated co-occurring concepts that would suggest an overall meaning.

Cognitive mapping: a visualization technique for either affect extraction or proximity analysis. Cognitive mapping attempts to create a model of the overall meaning of the text such as a graphic map that represents the relationships between concepts.

General steps for conducting a relational content analysis:

1. Determine the type of analysis: Once the sample has been selected, the researcher needs to determine what types of relationships to examine and the level of analysis: word, word sense, phrase, sentence, themes. 2. Reduce the text to categories and code for words or patterns. A researcher can code for existence of meanings or words. 3. Explore the relationship between concepts: once the words are coded, the text can be analyzed for the following:

Strength of relationship: degree to which two or more concepts are related.

Sign of relationship: are concepts positively or negatively related to each other?

Direction of relationship: the types of relationship that categories exhibit. For example, “X implies Y” or “X occurs before Y” or “if X then Y” or if X is the primary motivator of Y.

4. Code the relationships: a difference between conceptual and relational analysis is that the statements or relationships between concepts are coded. 5. Perform statistical analyses: explore differences or look for relationships among the identified variables during coding. 6. Map out representations: such as decision mapping and mental models.

Reliability and Validity

Reliability : Because of the human nature of researchers, coding errors can never be eliminated but only minimized. Generally, 80% is an acceptable margin for reliability. Three criteria comprise the reliability of a content analysis:

Stability: the tendency for coders to consistently re-code the same data in the same way over a period of time.

Reproducibility: tendency for a group of coders to classify categories membership in the same way.

Accuracy: extent to which the classification of text corresponds to a standard or norm statistically.

Validity : Three criteria comprise the validity of a content analysis:

Closeness of categories: this can be achieved by utilizing multiple classifiers to arrive at an agreed upon definition of each specific category. Using multiple classifiers, a concept category that may be an explicit variable can be broadened to include synonyms or implicit variables.

Conclusions: What level of implication is allowable? Do conclusions correctly follow the data? Are results explainable by other phenomena? This becomes especially problematic when using computer software for analysis and distinguishing between synonyms. For example, the word “mine,” variously denotes a personal pronoun, an explosive device, and a deep hole in the ground from which ore is extracted. Software can obtain an accurate count of that word’s occurrence and frequency, but not be able to produce an accurate accounting of the meaning inherent in each particular usage. This problem could throw off one’s results and make any conclusion invalid.

Generalizability of the results to a theory: dependent on the clear definitions of concept categories, how they are determined and how reliable they are at measuring the idea one is seeking to measure. Generalizability parallels reliability as much of it depends on the three criteria for reliability.

Advantages of Content Analysis

Directly examines communication using text

Allows for both qualitative and quantitative analysis

Provides valuable historical and cultural insights over time

Allows a closeness to data

Coded form of the text can be statistically analyzed

Unobtrusive means of analyzing interactions

Provides insight into complex models of human thought and language use

When done well, is considered a relatively “exact” research method

Content analysis is a readily-understood and an inexpensive research method

A more powerful tool when combined with other research methods such as interviews, observation, and use of archival records. It is very useful for analyzing historical material, especially for documenting trends over time.

Disadvantages of Content Analysis

Can be extremely time consuming

Is subject to increased error, particularly when relational analysis is used to attain a higher level of interpretation

Is often devoid of theoretical base, or attempts too liberally to draw meaningful inferences about the relationships and impacts implied in a study

Is inherently reductive, particularly when dealing with complex texts

Tends too often to simply consist of word counts

Often disregards the context that produced the text, as well as the state of things after the text is produced

Can be difficult to automate or computerize

Textbooks & Chapters

Berelson, Bernard. Content Analysis in Communication Research.New York: Free Press, 1952.

Busha, Charles H. and Stephen P. Harter. Research Methods in Librarianship: Techniques and Interpretation.New York: Academic Press, 1980.

de Sola Pool, Ithiel. Trends in Content Analysis. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1959.

Krippendorff, Klaus. Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, 1980.

Fielding, NG & Lee, RM. Using Computers in Qualitative Research. SAGE Publications, 1991. (Refer to Chapter by Seidel, J. ‘Method and Madness in the Application of Computer Technology to Qualitative Data Analysis’.)

Methodological Articles

Hsieh HF & Shannon SE. (2005). Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis.Qualitative Health Research. 15(9): 1277-1288.

Elo S, Kaarianinen M, Kanste O, Polkki R, Utriainen K, & Kyngas H. (2014). Qualitative Content Analysis: A focus on trustworthiness. Sage Open. 4:1-10.

Application Articles

Abroms LC, Padmanabhan N, Thaweethai L, & Phillips T. (2011). iPhone Apps for Smoking Cessation: A content analysis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 40(3):279-285.

Ullstrom S. Sachs MA, Hansson J, Ovretveit J, & Brommels M. (2014). Suffering in Silence: a qualitative study of second victims of adverse events. British Medical Journal, Quality & Safety Issue. 23:325-331.

Owen P. (2012).Portrayals of Schizophrenia by Entertainment Media: A Content Analysis of Contemporary Movies. Psychiatric Services. 63:655-659.

Choosing whether to conduct a content analysis by hand or by using computer software can be difficult. Refer to ‘Method and Madness in the Application of Computer Technology to Qualitative Data Analysis’ listed above in “Textbooks and Chapters” for a discussion of the issue.

QSR NVivo: http://www.qsrinternational.com/products.aspx

Atlas.ti: http://www.atlasti.com/webinars.html

R- RQDA package: http://rqda.r-forge.r-project.org/

Rolly Constable, Marla Cowell, Sarita Zornek Crawford, David Golden, Jake Hartvigsen, Kathryn Morgan, Anne Mudgett, Kris Parrish, Laura Thomas, Erika Yolanda Thompson, Rosie Turner, and Mike Palmquist. (1994-2012). Ethnography, Observational Research, and Narrative Inquiry. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University. Available at: https://writing.colostate.edu/guides/guide.cfm?guideid=63 .

As an introduction to Content Analysis by Michael Palmquist, this is the main resource on Content Analysis on the Web. It is comprehensive, yet succinct. It includes examples and an annotated bibliography. The information contained in the narrative above draws heavily from and summarizes Michael Palmquist’s excellent resource on Content Analysis but was streamlined for the purpose of doctoral students and junior researchers in epidemiology.

At Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, more detailed training is available through the Department of Sociomedical Sciences- P8785 Qualitative Research Methods.

Join the Conversation

Have a question about methods? Join us on Facebook

Data & Finance for Work & Life

Qualitative Content Analysis: a Simple Guide with Examples

Content analysis is a type of qualitative research (as opposed to quantitative research) that focuses on analyzing content in various mediums, the most common of which is written words in documents.

It’s a very common technique used in academia, especially for students working on theses and dissertations, but here we’re going to talk about how companies can use qualitative content analysis to improve their processes and increase revenue.

Whether you’re new to content analysis or a seasoned professor, this article provides all you need to know about how data analysts use content analysis to improve their business. It will also help you understand the relationship between content analysis and natural language processing — what some even call natural language content analysis.

Don’t forget, you can get the free Intro to Data Analysis eBook , which will ensure you build the right practical skills for success in your analytical endeavors.

What is qualitative content analysis, and what is it used for?

Any content analysis definition must consist of at least these three things: qualitative language , themes , and quantification .

In short, content analysis is the process of examining preselected words in video, audio, or written mediums and their context to identify themes, then quantifying them for statistical analysis in order to draw conclusions. More simply, it’s counting how often you see two words close to each other.

For example, let’s say I place in front of you an audio bit, a old video with a static image, and a document with lots of text but no titles or descriptions. At the start, you would have no idea what any of it was about.

Let’s say you transpose the video and audio recordings on paper. Then you use a counting software to count the top ten most used words, excluding prepositions (of, over, to, by) and articles (the, a), conjunctions (and, but, or) and other common words like “very.”

Your results are that the top 5 words are “candy,” “snow,” “cold,” and “sled.” These 5 words appear at least 25 times each, and the next highest word appears only 4 times. You also find that the words “snow” and “sled” appear adjacent to each other 95% of the time that “snow” appears.

Well, now you have performed a very elementary qualitative content analysis .

This means that you’re probably dealing with a text in which snow sleds are important. Snow sleds, thus, become a theme in these documents, which goes to the heart of qualitative content analysis.

The goal of qualitative content analysis is to organize text into a series of themes . This is opposed to quantitative content analysis, which aims to organize the text into categories .

Types of qualitative content analysis

If you’ve heard about content analysis, it was most likely in an academic setting. The term itself is common among PhD students and Masters students writing their dissertations and theses. In that context, the most common type of content analysis is document analysis.

There are many types of content analysis , including:

- Short- and long-form survey questions

- Focus group transcripts

- Interview transcripts

- Legislature

- Public records

- Comments sections

- Messaging platforms

This list gives you an idea for the possibilities and industries in which qualitative content analysis can be applied.

For example, marketing departments or public relations groups in major corporations might collect survey, focus groups, and interviews, then hand off the information to a data analyst who performs the content analysis.

A political analysis institution or Think Tank might look at legislature over time to identify potential emerging themes based on their slow introduction into policy margins. Perhaps it’s possible to identify certain beliefs in the senate and house of representatives before they enter the public discourse.

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) might perform an analysis on public records to see how to better serve their constituents. If they have access to public records, it would be possible to identify citizen characteristics that align with their goal.

Analysis logic: inductive vs deductive

There are two types of logic we can apply to qualitative content analysis: inductive and deductive. Inductive content analysis is more of an exploratory approach. We don’t know what patterns or ideas we’ll discover, so we go in with an open mind.

On the other hand, deductive content analysis involves starting with an idea and identifying how it appears in the text. For example, we may approach legislation on wildlife by looking for rules on hunting. Perhaps we think hunting with a knife is too dangerous, and we want to identify trends in the text.

Neither one is better per se, and they each have carry value in different contexts. For example, inductive content analysis is advantageous in situations where we want to identify author intent. Going in with a hypothesis can bias the way we look at the data, so the inductive method is better

Deductive content analysis is better when we want to target a term. For example, if we want to see how important knife hunting is in the legislation, we’re doing deductive content analysis.

Measurements: idea coding vs word frequency

Two main methodologies exist for analyzing the text itself: coding and word frequency. Idea coding is the manual process of reading through a text and “coding” ideas in a column on the right. The reason we call this coding is because we take ideas and themes expressed in many words, and turn them into one common phrase. This allows researchers to better understand how those ideas evolve. We will look at how to do this in word below.

In short, coding in the context qualitative content analysis follows 2 steps:

- Reading through the text one time

- Adding 2-5 word summaries each time a significant theme or idea appears

Word frequency is simply counting the number of times a word appears in a text, as well as its proximity to other words. In our “snow sled” example above, we counted the number of times a word appeared, as well as how often it appeared next to other words. There’s are online tool for this we’ll look at below.

In short, word frequency in the context of content analysis follows 2 steps:

- Decide whether you want to find a word, or just look at the most common words

- Use word’s Replace function for the first, or an online tool such as Text Analyzer for the second (we’ll look at these in more detail below).

Many data scientists consider coding as the only qualitative content analysis, since word frequency turns to counting the number of times a word appears, making is quantitative.

While there is merit to this claim, I personally do not consider word frequency a part of quantitative content analysis. The fact that we count the frequency of a word does not mean we can draw direct conclusions from it. In fact, without a researcher to provide context on the number of time a word appears, word frequency is useless. True quantitative research carries conclusive value on its own.

Measurements AND analysis logic

There are four ways to approach qualitative content analysis given our two measurement types and inductive/deductive logical approaches. You could do inductive coding, inductive word frequency, deductive coding, and deductive word frequency.

The two best are inductive coding and deductive word frequency. If you would like to discover a document, trying to search for specific words will not inform you about its contents, so inductive word frequency is un-insightful.

Likewise, if you’re looking for the presence of a specific idea, you do not want to go through the whole document to code just to find it, so deductive coding is not insightful. Here’s simple matrix to illustrate:

| Inductive (discovery) | Deductive (locating) | |

|---|---|---|

| (summarizing ideas) | GOOD. (Example: discovering author intent in a passage.) | BAD. (Example: coding an entire document to locate one idea.) |

| (counting word occurrences) | OK. (Example: trying to understand author intent by pulling to 10% of words.) | GOOD. (Example: locating and comparing a specific term in a text.) |

Qualitative content analysis example

We looked at a small example above, but let’s play out all of the above information in a real world example. I will post the link to the text source at the bottom of the article, but don’t look at it yet . Let’s jump in with a discovery mentality , meaning let’s use an inductive approach and code our way through each paragraph.

Qualitative Content Analysis Example Download

*Click the “1” superscript to the right for a link to the source text. 1

How to do qualitative content analysis

We could use word frequency analysis to find out which are the most common x% of words in the text (deductive word frequency), but this takes some time because we need to build a formula that excludes words that are common but that don’t have any value (a, the, but, and, etc).

As a shortcut, you can use online tools such as Text Analyzer and WordCounter , which will give you breakdowns by phrase length (6 words, 5 words, 4 words, etc), without excluding common terms. Here are a few insightful example using our text with 7 words:

Perhaps more insightfully, here is a list of 5 word combinations, which are much more common:

The downside to these tools is that you cannot find 2- and 1-word strings without excluding common words. This is a limitation, but it’s unlikely that the work required to get there is worth the value it brings.

OK. Now that we’ve seen how to go about coding our text into quantifiable data, let’s look at the deductive approach and try to figure out if the text contains a single word we’re looking for. (This is my favorite.)

Deductive word frequency

We know the text now because we’ve already looked through it. It’s about the process of becoming literate, namely, the elements that impact our ability to learn to read. But we only looked at the first four sections of the article, so there’s more to explore.

Let’s say we want to know how a household situation might impact a student’s ability to read . Instead of coding the entire article, we can simply look for this term and it’s synonyms. The process for deductive word frequency is the following:

- Identify your term

- Think of all the possible synonyms

- Use the word find function to see how many times they appear

- If you suspect that this word often comes in connection with others, try searching for both of them

In my example, the process would be:

- Parents, parent, home, house, household situation, household influence, parental, parental situation, at home, home situation

- Go to “Edit>Find>Replace…” This will enable you to locate the number of instances in which your word or combinations appear. We use the Replace window instead of the simply Find bar because it allows us to visualize the information.

- Accounted for in possible synonyms

The results: 0! None of these words appeared in the text, so we can conclude that this text has nothing to do with a child’s home life and its impact on his/her ability to learn to read. Here’s a picture:

Don’t Be Afraid of Content Analysis

Content analysis can be intimidating because it uses data analysis to quantify words. This article provides a starting point for your analysis, but to ensure you get 90% reliability in word coding, sign up to receive our eBook Beginner Content Analysis . I went from philosophy student to a data-heavy finance career, and I created it to cater to research and dissertation use cases.

Content analysis vs natural language processing

While similar, content analysis, even the deductive word frequency approach, and natural language processing (NLP) are not the same. The relationship is hierarchical. Natural language processing is a field of linguistics and data science that’s concerned with understanding the meaning behind language.

On the other hand, content analysis is a branch of natural language processing that focuses on the methodologies we discussed above: discovery-style coding (sometimes called “tokenization”) and word frequency (sometimes called the “bag of words” technique)

For example, we would use natural language processing to quantify huge amounts of linguistic information, turn it into row-and-column data, and run tests on it. NLP is incredibly complex in the details, which is why it’s nearly impossible to provide a synopsis or example technique here (we’ll provide them in coursework on AnalystAnswers.com ). However, content analysis only focuses on a few manual techniques.

Content analysis in marketing

Content analysis in marketing is the use of content analysis to improve marketing reach and conversions. has grown in importance over the past ten years. As digital platforms become more central to our understanding and interaction with others, we use them more.

We write out ideas, small texts. We post our thoughts on Facebook and Twitter, and we write blog posts like this one. But we also post videos on youtube and express ourselves in podcasts.

All of these mediums contain valuable information about who we are and what we might want to buy . A good marketer aims to leverage this information in three ways:

- Collect the data

- Analyze the data

- Modify his/her marketing messaging to better serve the consumer

- Pretend, with bots or employees, to be a consumer and craft messages that influence potential buyers

The challenge for marketers doing this is getting the rights to access this data. Indeed, data privacy laws have gone into play in the European Union (General Data Protection Regulation, or GDPR) as well as in Brazil (General Data Protection Law, or GDPL).

Content analysis vs narrative analysis

Content analysis is concerned with themes and ideas, whereas narrative analysis is concerned with the stories people express about themselves or others. Narrative analysis uses the same tools as content analysis, namely coding (or tokenization) and word frequency, but its focus is on narrative relationship rather than themes. This is easier to understand with an example. Let’s look at how we might code the following paragraph from the two perspectives:

I do not like green eggs and ham. I do not like them, Sam-I-Am. I do not like them here or there. I do not like them anywhere!

Content analysis : the ideas expressed include green eggs and ham. the narrator does not like them

Narrative analysis : the narrator speaks from first person. He has a relationship with Sam-I-Am. He orients himself with regards to time and space. he does not like green eggs and ham, and may be willing to act on that feeling.

Content analysis vs document analysis

Content analysis and document analysis are very similar, which explains why many people use them interchangeably. The core difference is that content analysis examines all mediums in which words appear , whereas document analysis only examines written documents .

For example, if I want to carry out content analysis on a master’s thesis in education, I would consult documents, videos, and audio files. I may transcribe the video and audio files into a document, but I wouldn’t exclude them form the beginning.

On the other hand, if I want to carry out document analysis on a master’s thesis, I would only use documents, excluding the other mediums from the start. The methodology is the same, but the scope is different. This dichotomy also explains why most academic researchers performing qualitative content analysis refer to the process as “document analysis.” They rarely look at other mediums.

Content Gap Analysis

Content gap analysis is a term common in the field of content marketing, but it applies to the analytical fields as well. In a sentence, content gap analysis is the process of examining a document or text and identifying the missing pieces, or “gap,” that it needs to be completed.

As you can imagine, a content marketer uses gap analysis to determine how to improve blog content. An analyst uses it for other reasons. For example, he/she may have a standard for documents that merit analysis. If a document does not meet the criteria, it must be rejected until it’s improved.

The key message here is that content gap analysis is not content analysis. It’s a way of measuring the distance an underperforming document is from an acceptable document. It is sometimes, but not always, used in a qualitative content analysis context.

- Link to Source Text [ ↩ ]

About the Author

Noah is the founder & Editor-in-Chief at AnalystAnswers. He is a transatlantic professional and entrepreneur with 5+ years of corporate finance and data analytics experience, as well as 3+ years in consumer financial products and business software. He started AnalystAnswers to provide aspiring professionals with accessible explanations of otherwise dense finance and data concepts. Noah believes everyone can benefit from an analytical mindset in growing digital world. When he's not busy at work, Noah likes to explore new European cities, exercise, and spend time with friends and family.

File available immediately.

Notice: JavaScript is required for this content.

Using Content Analysis

This guide provides an introduction to content analysis, a research methodology that examines words or phrases within a wide range of texts.

- Introduction to Content Analysis : Read about the history and uses of content analysis.

- Conceptual Analysis : Read an overview of conceptual analysis and its associated methodology.

- Relational Analysis : Read an overview of relational analysis and its associated methodology.

- Commentary : Read about issues of reliability and validity with regard to content analysis as well as the advantages and disadvantages of using content analysis as a research methodology.

- Examples : View examples of real and hypothetical studies that use content analysis.

- Annotated Bibliography : Complete list of resources used in this guide and beyond.

An Introduction to Content Analysis

Content analysis is a research tool used to determine the presence of certain words or concepts within texts or sets of texts. Researchers quantify and analyze the presence, meanings and relationships of such words and concepts, then make inferences about the messages within the texts, the writer(s), the audience, and even the culture and time of which these are a part. Texts can be defined broadly as books, book chapters, essays, interviews, discussions, newspaper headlines and articles, historical documents, speeches, conversations, advertising, theater, informal conversation, or really any occurrence of communicative language. Texts in a single study may also represent a variety of different types of occurrences, such as Palmquist's 1990 study of two composition classes, in which he analyzed student and teacher interviews, writing journals, classroom discussions and lectures, and out-of-class interaction sheets. To conduct a content analysis on any such text, the text is coded, or broken down, into manageable categories on a variety of levels--word, word sense, phrase, sentence, or theme--and then examined using one of content analysis' basic methods: conceptual analysis or relational analysis.

A Brief History of Content Analysis

Historically, content analysis was a time consuming process. Analysis was done manually, or slow mainframe computers were used to analyze punch cards containing data punched in by human coders. Single studies could employ thousands of these cards. Human error and time constraints made this method impractical for large texts. However, despite its impracticality, content analysis was already an often utilized research method by the 1940's. Although initially limited to studies that examined texts for the frequency of the occurrence of identified terms (word counts), by the mid-1950's researchers were already starting to consider the need for more sophisticated methods of analysis, focusing on concepts rather than simply words, and on semantic relationships rather than just presence (de Sola Pool 1959). While both traditions still continue today, content analysis now is also utilized to explore mental models, and their linguistic, affective, cognitive, social, cultural and historical significance.

Uses of Content Analysis

Perhaps due to the fact that it can be applied to examine any piece of writing or occurrence of recorded communication, content analysis is currently used in a dizzying array of fields, ranging from marketing and media studies, to literature and rhetoric, ethnography and cultural studies, gender and age issues, sociology and political science, psychology and cognitive science, and many other fields of inquiry. Additionally, content analysis reflects a close relationship with socio- and psycholinguistics, and is playing an integral role in the development of artificial intelligence. The following list (adapted from Berelson, 1952) offers more possibilities for the uses of content analysis:

- Reveal international differences in communication content

- Detect the existence of propaganda

- Identify the intentions, focus or communication trends of an individual, group or institution

- Describe attitudinal and behavioral responses to communications

- Determine psychological or emotional state of persons or groups

Types of Content Analysis

In this guide, we discuss two general categories of content analysis: conceptual analysis and relational analysis. Conceptual analysis can be thought of as establishing the existence and frequency of concepts most often represented by words of phrases in a text. For instance, say you have a hunch that your favorite poet often writes about hunger. With conceptual analysis you can determine how many times words such as hunger, hungry, famished, or starving appear in a volume of poems. In contrast, relational analysis goes one step further by examining the relationships among concepts in a text. Returning to the hunger example, with relational analysis, you could identify what other words or phrases hunger or famished appear next to and then determine what different meanings emerge as a result of these groupings.

Conceptual Analysis

Traditionally, content analysis has most often been thought of in terms of conceptual analysis. In conceptual analysis, a concept is chosen for examination, and the analysis involves quantifying and tallying its presence. Also known as thematic analysis [although this term is somewhat problematic, given its varied definitions in current literature--see Palmquist, Carley, & Dale (1997) vis-a-vis Smith (1992)], the focus here is on looking at the occurrence of selected terms within a text or texts, although the terms may be implicit as well as explicit. While explicit terms obviously are easy to identify, coding for implicit terms and deciding their level of implication is complicated by the need to base judgments on a somewhat subjective system. To attempt to limit the subjectivity, then (as well as to limit problems of reliability and validity ), coding such implicit terms usually involves the use of either a specialized dictionary or contextual translation rules. And sometimes, both tools are used--a trend reflected in recent versions of the Harvard and Lasswell dictionaries.

Methods of Conceptual Analysis

Conceptual analysis begins with identifying research questions and choosing a sample or samples. Once chosen, the text must be coded into manageable content categories. The process of coding is basically one of selective reduction . By reducing the text to categories consisting of a word, set of words or phrases, the researcher can focus on, and code for, specific words or patterns that are indicative of the research question.

An example of a conceptual analysis would be to examine several Clinton speeches on health care, made during the 1992 presidential campaign, and code them for the existence of certain words. In looking at these speeches, the research question might involve examining the number of positive words used to describe Clinton's proposed plan, and the number of negative words used to describe the current status of health care in America. The researcher would be interested only in quantifying these words, not in examining how they are related, which is a function of relational analysis. In conceptual analysis, the researcher simply wants to examine presence with respect to his/her research question, i.e. is there a stronger presence of positive or negative words used with respect to proposed or current health care plans, respectively.

Once the research question has been established, the researcher must make his/her coding choices with respect to the eight category coding steps indicated by Carley (1992).

Steps for Conducting Conceptual Analysis

The following discussion of steps that can be followed to code a text or set of texts during conceptual analysis use campaign speeches made by Bill Clinton during the 1992 presidential campaign as an example. To read about each step, click on the items in the list below:

- Decide the level of analysis.

First, the researcher must decide upon the level of analysis . With the health care speeches, to continue the example, the researcher must decide whether to code for a single word, such as "inexpensive," or for sets of words or phrases, such as "coverage for everyone."

- Decide how many concepts to code for.

The researcher must now decide how many different concepts to code for. This involves developing a pre-defined or interactive set of concepts and categories. The researcher must decide whether or not to code for every single positive or negative word that appears, or only certain ones that the researcher determines are most relevant to health care. Then, with this pre-defined number set, the researcher has to determine how much flexibility he/she allows him/herself when coding. The question of whether the researcher codes only from this pre-defined set, or allows him/herself to add relevant categories not included in the set as he/she finds them in the text, must be answered. Determining a certain number and set of concepts allows a researcher to examine a text for very specific things, keeping him/her on task. But introducing a level of coding flexibility allows new, important material to be incorporated into the coding process that could have significant bearings on one's results.

- Decide whether to code for existence or frequency of a concept.

After a certain number and set of concepts are chosen for coding , the researcher must answer a key question: is he/she going to code for existence or frequency ? This is important, because it changes the coding process. When coding for existence, "inexpensive" would only be counted once, no matter how many times it appeared. This would be a very basic coding process and would give the researcher a very limited perspective of the text. However, the number of times "inexpensive" appears in a text might be more indicative of importance. Knowing that "inexpensive" appeared 50 times, for example, compared to 15 appearances of "coverage for everyone," might lead a researcher to interpret that Clinton is trying to sell his health care plan based more on economic benefits, not comprehensive coverage. Knowing that "inexpensive" appeared, but not that it appeared 50 times, would not allow the researcher to make this interpretation, regardless of whether it is valid or not.

- Decide on how you will distinguish among concepts.

The researcher must next decide on the , i.e. whether concepts are to be coded exactly as they appear, or if they can be recorded as the same even when they appear in different forms. For example, "expensive" might also appear as "expensiveness." The research needs to determine if the two words mean radically different things to him/her, or if they are similar enough that they can be coded as being the same thing, i.e. "expensive words." In line with this, is the need to determine the level of implication one is going to allow. This entails more than subtle differences in tense or spelling, as with "expensive" and "expensiveness." Determining the level of implication would allow the researcher to code not only for the word "expensive," but also for words that imply "expensive." This could perhaps include technical words, jargon, or political euphemism, such as "economically challenging," that the researcher decides does not merit a separate category, but is better represented under the category "expensive," due to its implicit meaning of "expensive."

- Develop rules for coding your texts.

After taking the generalization of concepts into consideration, a researcher will want to create translation rules that will allow him/her to streamline and organize the coding process so that he/she is coding for exactly what he/she wants to code for. Developing a set of rules helps the researcher insure that he/she is coding things consistently throughout the text, in the same way every time. If a researcher coded "economically challenging" as a separate category from "expensive" in one paragraph, then coded it under the umbrella of "expensive" when it occurred in the next paragraph, his/her data would be invalid. The interpretations drawn from that data will subsequently be invalid as well. Translation rules protect against this and give the coding process a crucial level of consistency and coherence.

- Decide what to do with "irrelevant" information.

The next choice a researcher must make involves irrelevant information . The researcher must decide whether irrelevant information should be ignored (as Weber, 1990, suggests), or used to reexamine and/or alter the coding scheme. In the case of this example, words like "and" and "the," as they appear by themselves, would be ignored. They add nothing to the quantification of words like "inexpensive" and "expensive" and can be disregarded without impacting the outcome of the coding.

- Code the texts.

Once these choices about irrelevant information are made, the next step is to code the text. This is done either by hand, i.e. reading through the text and manually writing down concept occurrences, or through the use of various computer programs. Coding with a computer is one of contemporary conceptual analysis' greatest assets. By inputting one's categories, content analysis programs can easily automate the coding process and examine huge amounts of data, and a wider range of texts, quickly and efficiently. But automation is very dependent on the researcher's preparation and category construction. When coding is done manually, a researcher can recognize errors far more easily. A computer is only a tool and can only code based on the information it is given. This problem is most apparent when coding for implicit information, where category preparation is essential for accurate coding.

- Analyze your results.

Once the coding is done, the researcher examines the data and attempts to draw whatever conclusions and generalizations are possible. Of course, before these can be drawn, the researcher must decide what to do with the information in the text that is not coded. One's options include either deleting or skipping over unwanted material, or viewing all information as relevant and important and using it to reexamine, reassess and perhaps even alter one's coding scheme. Furthermore, given that the conceptual analyst is dealing only with quantitative data, the levels of interpretation and generalizability are very limited. The researcher can only extrapolate as far as the data will allow. But it is possible to see trends, for example, that are indicative of much larger ideas. Using the example from step three, if the concept "inexpensive" appears 50 times, compared to 15 appearances of "coverage for everyone," then the researcher can pretty safely extrapolate that there does appear to be a greater emphasis on the economics of the health care plan, as opposed to its universal coverage for all Americans. It must be kept in mind that conceptual analysis, while extremely useful and effective for providing this type of information when done right, is limited by its focus and the quantitative nature of its examination. To more fully explore the relationships that exist between these concepts, one must turn to relational analysis.

Relational Analysis

Relational analysis, like conceptual analysis, begins with the act of identifying concepts present in a given text or set of texts. However, relational analysis seeks to go beyond presence by exploring the relationships between the concepts identified. Relational analysis has also been termed semantic analysis (Palmquist, Carley, & Dale, 1997). In other words, the focus of relational analysis is to look for semantic, or meaningful, relationships. Individual concepts, in and of themselves, are viewed as having no inherent meaning. Rather, meaning is a product of the relationships among concepts in a text. Carley (1992) asserts that concepts are "ideational kernels;" these kernels can be thought of as symbols which acquire meaning through their connections to other symbols.

Theoretical Influences on Relational Analysis

The kind of analysis that researchers employ will vary significantly according to their theoretical approach. Key theoretical approaches that inform content analysis include linguistics and cognitive science.

Linguistic approaches to content analysis focus analysis of texts on the level of a linguistic unit, typically single clause units. One example of this type of research is Gottschalk (1975), who developed an automated procedure which analyzes each clause in a text and assigns it a numerical score based on several emotional/psychological scales. Another technique is to code a text grammatically into clauses and parts of speech to establish a matrix representation (Carley, 1990).

Approaches that derive from cognitive science include the creation of decision maps and mental models. Decision maps attempt to represent the relationship(s) between ideas, beliefs, attitudes, and information available to an author when making a decision within a text. These relationships can be represented as logical, inferential, causal, sequential, and mathematical relationships. Typically, two of these links are compared in a single study, and are analyzed as networks. For example, Heise (1987) used logical and sequential links to examine symbolic interaction. This methodology is thought of as a more generalized cognitive mapping technique, rather than the more specific mental models approach.

Mental models are groups or networks of interrelated concepts that are thought to reflect conscious or subconscious perceptions of reality. According to cognitive scientists, internal mental structures are created as people draw inferences and gather information about the world. Mental models are a more specific approach to mapping because beyond extraction and comparison because they can be numerically and graphically analyzed. Such models rely heavily on the use of computers to help analyze and construct mapping representations. Typically, studies based on this approach follow five general steps:

- Identifing concepts

- Defining relationship types

- Coding the text on the basis of 1 and 2

- Coding the statements

- Graphically displaying and numerically analyzing the resulting maps

To create the model, a researcher converts a text into a map of concepts and relations; the map is then analyzed on the level of concepts and statements, where a statement consists of two concepts and their relationship. Carley (1990) asserts that this makes possible the comparison of a wide variety of maps, representing multiple sources, implicit and explicit information, as well as socially shared cognitions.

Relational Analysis: Overview of Methods

As with other sorts of inquiry, initial choices with regard to what is being studied and/or coded for often determine the possibilities of that particular study. For relational analysis, it is important to first decide which concept type(s) will be explored in the analysis. Studies have been conducted with as few as one and as many as 500 concept categories. Obviously, too many categories may obscure your results and too few can lead to unreliable and potentially invalid conclusions. Therefore, it is important to allow the context and necessities of your research to guide your coding procedures.

The steps to relational analysis that we consider in this guide suggest some of the possible avenues available to a researcher doing content analysis. We provide an example to make the process easier to grasp. However, the choices made within the context of the example are but only a few of many possibilities. The diversity of techniques available suggests that there is quite a bit of enthusiasm for this mode of research. Once a procedure is rigorously tested, it can be applied and compared across populations over time. The process of relational analysis has achieved a high degree of computer automation but still is, like most forms of research, time consuming. Perhaps the strongest claim that can be made is that it maintains a high degree of statistical rigor without losing the richness of detail apparent in even more qualitative methods.

Three Subcategories of Relational Analysis

Affect extraction: This approach provides an emotional evaluation of concepts explicit in a text. It is problematic because emotion may vary across time and populations. Nevertheless, when extended it can be a potent means of exploring the emotional/psychological state of the speaker and/or writer. Gottschalk (1995) provides an example of this type of analysis. By assigning concepts identified a numeric value on corresponding emotional/psychological scales that can then be statistically examined, Gottschalk claims that the emotional/psychological state of the speaker or writer can be ascertained via their verbal behavior.

Proximity analysis: This approach, on the other hand, is concerned with the co-occurrence of explicit concepts in the text. In this procedure, the text is defined as a string of words. A given length of words, called a window , is determined. The window is then scanned across a text to check for the co-occurrence of concepts. The result is the creation of a concept determined by the concept matrix . In other words, a matrix, or a group of interrelated, co-occurring concepts, might suggest a certain overall meaning. The technique is problematic because the window records only explicit concepts and treats meaning as proximal co-occurrence. Other techniques such as clustering, grouping, and scaling are also useful in proximity analysis.

Cognitive mapping: This approach is one that allows for further analysis of the results from the two previous approaches. It attempts to take the above processes one step further by representing these relationships visually for comparison. Whereas affective and proximal analysis function primarily within the preserved order of the text, cognitive mapping attempts to create a model of the overall meaning of the text. This can be represented as a graphic map that represents the relationships between concepts.

In this manner, cognitive mapping lends itself to the comparison of semantic connections across texts. This is known as map analysis which allows for comparisons to explore "how meanings and definitions shift across people and time" (Palmquist, Carley, & Dale, 1997). Maps can depict a variety of different mental models (such as that of the text, the writer/speaker, or the social group/period), according to the focus of the researcher. This variety is indicative of the theoretical assumptions that support mapping: mental models are representations of interrelated concepts that reflect conscious or subconscious perceptions of reality; language is the key to understanding these models; and these models can be represented as networks (Carley, 1990). Given these assumptions, it's not surprising to see how closely this technique reflects the cognitive concerns of socio-and psycholinguistics, and lends itself to the development of artificial intelligence models.

Steps for Conducting Relational Analysis

The following discussion of the steps (or, perhaps more accurately, strategies) that can be followed to code a text or set of texts during relational analysis. These explanations are accompanied by examples of relational analysis possibilities for statements made by Bill Clinton during the 1998 hearings.

- Identify the Question.

The question is important because it indicates where you are headed and why. Without a focused question, the concept types and options open to interpretation are limitless and therefore the analysis difficult to complete. Possibilities for the Hairy Hearings of 1998 might be:

What did Bill Clinton say in the speech? OR What concrete information did he present to the public?

- Choose a sample or samples for analysis.

Once the question has been identified, the researcher must select sections of text/speech from the hearings in which Bill Clinton may have not told the entire truth or is obviously holding back information. For relational content analysis, the primary consideration is how much information to preserve for analysis. One must be careful not to limit the results by doing so, but the researcher must also take special care not to take on so much that the coding process becomes too heavy and extensive to supply worthwhile results.

- Determine the type of analysis.

Once the sample has been chosen for analysis, it is necessary to determine what type or types of relationships you would like to examine. There are different subcategories of relational analysis that can be used to examine the relationships in texts.

In this example, we will use proximity analysis because it is concerned with the co-occurrence of explicit concepts in the text. In this instance, we are not particularly interested in affect extraction because we are trying to get to the hard facts of what exactly was said rather than determining the emotional considerations of speaker and receivers surrounding the speech which may be unrecoverable.

Once the subcategory of analysis is chosen, the selected text must be reviewed to determine the level of analysis. The researcher must decide whether to code for a single word, such as "perhaps," or for sets of words or phrases like "I may have forgotten."

- Reduce the text to categories and code for words or patterns.

At the simplest level, a researcher can code merely for existence. This is not to say that simplicity of procedure leads to simplistic results. Many studies have successfully employed this strategy. For example, Palmquist (1990) did not attempt to establish the relationships among concept terms in the classrooms he studied; his study did, however, look at the change in the presence of concepts over the course of the semester, comparing a map analysis from the beginning of the semester to one constructed at the end. On the other hand, the requirement of one's specific research question may necessitate deeper levels of coding to preserve greater detail for analysis.

In relation to our extended example, the researcher might code for how often Bill Clinton used words that were ambiguous, held double meanings, or left an opening for change or "re-evaluation." The researcher might also choose to code for what words he used that have such an ambiguous nature in relation to the importance of the information directly related to those words.

- Explore the relationships between concepts (Strength, Sign & Direction).

Once words are coded, the text can be analyzed for the relationships among the concepts set forth. There are three concepts which play a central role in exploring the relations among concepts in content analysis.

- Strength of Relationship: Refers to the degree to which two or more concepts are related. These relationships are easiest to analyze, compare, and graph when all relationships between concepts are considered to be equal. However, assigning strength to relationships retains a greater degree of the detail found in the original text. Identifying strength of a relationship is key when determining whether or not words like unless, perhaps, or maybe are related to a particular section of text, phrase, or idea.

- Sign of a Relationship: Refers to whether or not the concepts are positively or negatively related. To illustrate, the concept "bear" is negatively related to the concept "stock market" in the same sense as the concept "bull" is positively related. Thus "it's a bear market" could be coded to show a negative relationship between "bear" and "market". Another approach to coding for strength entails the creation of separate categories for binary oppositions. The above example emphasizes "bull" as the negation of "bear," but could be coded as being two separate categories, one positive and one negative. There has been little research to determine the benefits and liabilities of these differing strategies. Use of Sign coding for relationships in regard to the hearings my be to find out whether or not the words under observation or in question were used adversely or in favor of the concepts (this is tricky, but important to establishing meaning).

- Direction of the Relationship: Refers to the type of relationship categories exhibit. Coding for this sort of information can be useful in establishing, for example, the impact of new information in a decision making process. Various types of directional relationships include, "X implies Y," "X occurs before Y" and "if X then Y," or quite simply the decision whether concept X is the "prime mover" of Y or vice versa. In the case of the 1998 hearings, the researcher might note that, "maybe implies doubt," "perhaps occurs before statements of clarification," and "if possibly exists, then there is room for Clinton to change his stance." In some cases, concepts can be said to be bi-directional, or having equal influence. This is equivalent to ignoring directionality. Both approaches are useful, but differ in focus. Coding all categories as bi-directional is most useful for exploratory studies where pre-coding may influence results, and is also most easily automated, or computer coded.

- Code the relationships.

One of the main differences between conceptual analysis and relational analysis is that the statements or relationships between concepts are coded. At this point, to continue our extended example, it is important to take special care with assigning value to the relationships in an effort to determine whether the ambiguous words in Bill Clinton's speech are just fillers, or hold information about the statements he is making.

- Perform Statisical Analyses.

This step involves conducting statistical analyses of the data you've coded during your relational analysis. This may involve exploring for differences or looking for relationships among the variables you've identified in your study.

- Map out the Representations.

In addition to statistical analysis, relational analysis often leads to viewing the representations of the concepts and their associations in a text (or across texts) in a graphical -- or map -- form. Relational analysis is also informed by a variety of different theoretical approaches: linguistic content analysis, decision mapping, and mental models.

The authors of this guide have created the following commentaries on content analysis.

Issues of Reliability & Validity

The issues of reliability and validity are concurrent with those addressed in other research methods. The reliability of a content analysis study refers to its stability , or the tendency for coders to consistently re-code the same data in the same way over a period of time; reproducibility , or the tendency for a group of coders to classify categories membership in the same way; and accuracy , or the extent to which the classification of a text corresponds to a standard or norm statistically. Gottschalk (1995) points out that the issue of reliability may be further complicated by the inescapably human nature of researchers. For this reason, he suggests that coding errors can only be minimized, and not eliminated (he shoots for 80% as an acceptable margin for reliability).

On the other hand, the validity of a content analysis study refers to the correspondence of the categories to the conclusions , and the generalizability of results to a theory.

The validity of categories in implicit concept analysis, in particular, is achieved by utilizing multiple classifiers to arrive at an agreed upon definition of the category. For example, a content analysis study might measure the occurrence of the concept category "communist" in presidential inaugural speeches. Using multiple classifiers, the concept category can be broadened to include synonyms such as "red," "Soviet threat," "pinkos," "godless infidels" and "Marxist sympathizers." "Communist" is held to be the explicit variable, while "red," etc. are the implicit variables.

The overarching problem of concept analysis research is the challenge-able nature of conclusions reached by its inferential procedures. The question lies in what level of implication is allowable, i.e. do the conclusions follow from the data or are they explainable due to some other phenomenon? For occurrence-specific studies, for example, can the second occurrence of a word carry equal weight as the ninety-ninth? Reasonable conclusions can be drawn from substantive amounts of quantitative data, but the question of proof may still remain unanswered.

This problem is again best illustrated when one uses computer programs to conduct word counts. The problem of distinguishing between synonyms and homonyms can completely throw off one's results, invalidating any conclusions one infers from the results. The word "mine," for example, variously denotes a personal pronoun, an explosive device, and a deep hole in the ground from which ore is extracted. One may obtain an accurate count of that word's occurrence and frequency, but not have an accurate accounting of the meaning inherent in each particular usage. For example, one may find 50 occurrences of the word "mine." But, if one is only looking specifically for "mine" as an explosive device, and 17 of the occurrences are actually personal pronouns, the resulting 50 is an inaccurate result. Any conclusions drawn as a result of that number would render that conclusion invalid.

The generalizability of one's conclusions, then, is very dependent on how one determines concept categories, as well as on how reliable those categories are. It is imperative that one defines categories that accurately measure the idea and/or items one is seeking to measure. Akin to this is the construction of rules. Developing rules that allow one, and others, to categorize and code the same data in the same way over a period of time, referred to as stability , is essential to the success of a conceptual analysis. Reproducibility , not only of specific categories, but of general methods applied to establishing all sets of categories, makes a study, and its subsequent conclusions and results, more sound. A study which does this, i.e. in which the classification of a text corresponds to a standard or norm, is said to have accuracy .

Advantages of Content Analysis

Content analysis offers several advantages to researchers who consider using it. In particular, content analysis:

- looks directly at communication via texts or transcripts, and hence gets at the central aspect of social interaction

- can allow for both quantitative and qualitative operations

- can provides valuable historical/cultural insights over time through analysis of texts

- allows a closeness to text which can alternate between specific categories and relationships and also statistically analyzes the coded form of the text

- can be used to interpret texts for purposes such as the development of expert systems (since knowledge and rules can both be coded in terms of explicit statements about the relationships among concepts)

- is an unobtrusive means of analyzing interactions

- provides insight into complex models of human thought and language use

Disadvantages of Content Analysis

Content analysis suffers from several disadvantages, both theoretical and procedural. In particular, content analysis:

- can be extremely time consuming

- is subject to increased error, particularly when relational analysis is used to attain a higher level of interpretation

- is often devoid of theoretical base, or attempts too liberally to draw meaningful inferences about the relationships and impacts implied in a study

- is inherently reductive, particularly when dealing with complex texts

- tends too often to simply consist of word counts

- often disregards the context that produced the text, as well as the state of things after the text is produced

- can be difficult to automate or computerize

The Palmquist, Carley and Dale study, a summary of "Applications of Computer-Aided Text Analysis: Analyzing Literary and Non-Literary Texts" (1997) is an example of two studies that have been conducted using both conceptual and relational analysis. The Problematic Text for Content Analysis shows the differences in results obtained by a conceptual and a relational approach to a study.

Related Information: Example of a Problematic Text for Content Analysis

In this example, both students observed a scientist and were asked to write about the experience.

Student A: I found that scientists engage in research in order to make discoveries and generate new ideas. Such research by scientists is hard work and often involves collaboration with other scientists which leads to discoveries which make the scientists famous. Such collaboration may be informal, such as when they share new ideas over lunch, or formal, such as when they are co-authors of a paper.