It's Lit Teaching

Scaffolded High School English Resources

- Creative Writing

- Teachers Pay Teachers Tips

- Shop My Teaching Resources!

6 Ways You Should Be Scaffolding Student Writing

You’ve probably heard a million times that you should be using differentiated instruction in your classroom. If you’re in a stricter building, it may even be required that you document your differentiation strategies. But how, exactly, are we supposed to differentiate writing instruction for our advanced, gifted, special education, trauma-sensitive, and ELL learners in a single class period!? It seems impossible! At least it does until you consider scaffolding writing instruction.

Why Use A Scaffolding Technique in Teaching Writing?

I’ve written about scaffolding in the creative writing classroom specifically before. That post is great for an introduction to the idea of scaffolding if that’s a new term for you. But scaffolding is great for all writing instruction–not just creative writing.

Scaffolding refers to the tools we give students to help them take baby steps towards conquering a bigger task. Before they write that ten-page paper, they’re going to have to know how to write an introduction.

How can we set our students up for writing success? In this post, I hope to share some tricks and techniques that have helped students in my own classroom.

Scaffolding Writing for Struggling Students

Scaffolding, which basically involves breaking down large tasks into smaller steps, is helpful for all learners. Yes, even your gifted students will benefit from the same scaffolding techniques that your ELLs are leaning on.

While your struggling learners may be seemingly incapable of tackling that big essay without some scaffolding support, forcing your advanced students to try various scaffolds can help them too.

When they’re made to slow down and really examine every step, advanced students will be unable to rush through assignments and turn in work that meets the requirements but is below the student’s full ability.

Scaffolding Writing Assignments

Pretty much any writing assignment can be scaffolded for students. Creating scaffolding just means that you’re breaking down a task into smaller components or steps. Scaffolding can be anything that helps the students conceptualize what their final product should look like, put their ideas together, or even help them reflect on their work.

When I first started teaching, I looked at the curriculum and thought, “We just don’t have time for all of that!” I know better now.

Scaffolding in your writing instruction is necessary. Sometimes in life, we have to slow down, so we can speed up later. Writing instruction is no different.

When we take it slow in the beginning, we’re setting ourselves (and our students) up for faster, better work in the future!

Slow down to speed up. Scaffold for more structural integrity in writing.

Ok, sounds well and good, right? But how exactly do we do that without sacrificing our entire curriculum? How do we scaffold without spoon-feeding our students the answers?

Scaffolding Strategies with Writing Scaffolds Examples

Scaffolding Tip #1: Tap into Prior Knowledge

One way to make struggling students feel more comfortable doing the work is to show them how much they already know.

You’re probably already familiar with the variety of ways we teachers help students activate their prior knowledge: K-W-L charts, brainstorming, concept maps, etc. When students can see all that they already know, venturing into new territory seems less scary.

An Example of Activating Prior Knowledge

One of my favorite ways to activate prior knowledge is through anticipation guides. In my free Internment Anticipation Guide , students read through various statements deciding whether they agree or disagree with each.

Then, they discuss these statements with partners and groups, attempting to persuade others to see their side.

By the time we discuss each statement as a whole class, students are passionately debating. They’re not worrying about what they don’t know–they’re ready to dive deeper into the topics.

Scaffolding Tip #2: Give Students a Framework

Frameworks help all kinds of writers with all kinds of writing. Whether you’re writing a formal essay, a blog post, or even an Instagram post, if you’re doing it successfully, there’s probably a method to how you structure the content.

If even confident writers use frameworks, then our struggling students definitely need one!

The typical five-paragraph essay is a great example of a writing framework. In general, all five-paragraph essays follow the same framework: one introductory paragraph, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion paragraph.

There’s even a framework for each of those paragraphs. If we zoom in on the introduction paragraph, for example, we’ll see that it typically starts with a hook, leads with background information, and ends with a thesis.

Once students understand the framework and how it all works together, all they have to worry about is the content and their writing craft. The overwhelm is gone. The task no longer seems daunting or impossible.

An Example of a Scaffolding Framework

In my school, we use a C-E-R framework for all of our school’s academic writing–from English to gym class.

I break down the C-E-R framework in detail in this post , but basically all of our academic writing starts with a claim, which is supported by evidence, which in turn is explained through the students’ reasoning.

Once students learn the framework in freshman year, they understand the expectations. Throughout their four years, they’ll apply that framework to writing for all content areas, for writing of different length requirements, and to writing for different audiences.

Students no longer have to wonder about the expectations or how to get started. Instead, they can spend those four years working on skills: improving their transitions, citing evidence correctly, correcting their punctuation, etc.

Teaching a framework is a great example of slowing down to speed up. In freshman year, teachers hammer claim, evidence, and reasoning into the curriculum. That leaves students ready to tackle bigger, more complex writing in years to come.

It doesn’t have to be a four-year process, though. I review C-E-R over the course of a couple of weeks in my senior class. For students new to our school, it’s the first time they are exposed to it, but with the help of their peers they catch on quickly.

Scaffolding Technique #3: Teaching the Writing Process

This one is probably the best-known version of scaffolding for any English teacher. The writing process is basically a framework for how to write . It consists of six steps: brainstorming, outlining, creating a rough draft, evaluating that work, then sculpting a final draft, before the optional step of publishing.

You’ve probably implemented the writing process before in regards to an essay, but the writing process is just that–a process. It can be applied to pretty much any writing task.

Except, I hear you say, we don’t really have time to apply the writing process to every single thing we do in class.

And we don’t! I wouldn’t have students complete the whole writing process for informal assignments or journal writing, for example.

An Example of Scaffolding the Writing Process

But we also don’t have to save it just for essay writing. In fact, exposing students to a variety of writing tasks and showing them that this process WORKS for any kind of writing is probably a better use of everyone’s time than hammering away at another five-paragraph essay.

For example, in my Social Justice Mini-Research Project , students create a pamphlet around a social justice issue of their choosing. This assignment is shorter and more creative than a traditional essay. Plus, it involves choice (point for differentiation!) which I always like to include where I can.

In this resource , I’ve broken down the writing process for the teacher and the student.

Students look at work from the historical activist group The White Rose for inspiration, before brainstorming and doing some research around their own social justice cause.

Then, they use the included graphic organizers (scaffolding in and of itself) to outline the pamphlet they create.

From there, students can create, edit, and publish in whatever ways work best for the student, class, or teacher (I do include some publishing suggestions in the teacher’s guide).

The resource breaks down the writing process–choosing a topic, doing research, analyzing a mentor text, outlining, etc.–to help students. Walking students through this process–and teaching the process–is a scaffolding technique that benefits any writing instruction.

Scaffolding Technique #4: Show Examples

Another common scaffolding strategy is to show examples. This sounds overly simple, but students just cannot see enough examples.

And they shouldn’t just see good examples! Showing students examples of bad or mediocre writing can be just as powerful–so long as you discuss why the examples are subpar.

Perhaps my favorite use of examples is through mentor texts. Mentor texts are expert examples of the type of writing you’d like to teach.

An Example of Using Mentor Texts to Scaffold

My Author Study Project is a deep-dive into this concept.

Students select an author to study. Then, over the duration of the project, students read and take notes on their chosen author’s style. They analyze the subject matter, the tone, and the imagery style of their mentor author.

Once they’ve reached an understanding of the author’s style, they try to mimic that style in their own original work!

Of course, using examples doesn’t have to turn into a full-blown author study or project.

Showing students examples of “ok” essays versus excellent essays can really encourage them to put forth the extra effort. Showing students several examples of how to apply a skill (say, citing evidence) can also be beneficial.

Using examples throughout your class is not only a great scaffolding technique but a great differentiation one as well. Showing an exemplar paper will encourage struggling students to get help, clarification, or use extra resources. Meanwhile, striving students will be pushed even further.

When do you show examples?

You should show examples as often as you can. When you assign the assignment, it’s good to have a few examples of what the final product should look like.

Then, as students have begun to grapple with the writing, it’s nice to have a few examples of techniques. Or even examples of how past students have managed the same struggles.

Then, at the end of the assignment, right before it’s due, it’s great to bust out some of those stellar examples again. (This might also be a good time to show some examples that did not make the cut.)

Scaffolding Technique #5: Graphic Organizers

I love me a good graphic organizer! I use them all the time for creative writing projects, but they can be created, used, and applied to pretty much any topic or project.

A graphic organizer is pretty much just what it sounds like: a way to organize ideas and thoughts visually.

When my students will be working on a writing assignment, I like to create graphic organizers that break down the writing into step-by-step processes . If possible, I’ll include tips or prompting questions on the worksheet as well.

If you’re using any kind of framework, I highly recommend turning it into a graphic organizer for students. Even if it’s just a checklist that students can use to make sure they’re covering the requirements.

I don’t know why, but even a few empty boxes seem much more accessible to struggling students than a blank notebook page.

An Example of Using Graphic Organizers Prior to Writing

With my Figurative Language Photo Writing Activity , students practice using figurative language techniques to describe various landscapes.

The resource includes graphic organizers for students to use to brainstorm sensory figurative language that they will be able to use in their final description.

Scaffolding Technique #6: Encourage Peer Discussion and Feedback

One more scaffolding strategy is maybe one of the most important: encourage students to discuss ideas.

We can teach our hearts out; we can teach until we have used every level of Bloom’s taxonomy twice. It won’t matter. Students will always learn best from their peers.

Kids learn from kids. Maybe it’s because their peers “speak their language”. Maybe it’s because their peers are less intimidating than educators? But when I’m stuck explaining a concept, having another student show or explain it can often do the trick.

During work time, I love hearing students help one another. While some other teachers would intervene to make sure students learn correctly, I love hearing student explanations of ideas.

This goes, of course, for open, opinion-based discussions as well. I love hearing students’ takes on literature that we read. Often, they’ll question or bounce ideas off of one another, and I even end up learning from them!

An Example of Incorporating Class Discussions

One of my favorite activities of the year is my The Hate U Give Discussion Activity . During the round table discussion, students talk to one another about some really BIG life questions. They are required to use examples and quotes from the book to back up their thoughts, but students really shine during this activity.

Expecting students to show their perspective and respectfully challenge others’ is one of the greatest life lessons you could possibly teach. Students open up each other’s eyes more so than I will ever be able to do.

Slowly Remove Scaffolding

Scaffolding is a great tool for writing, but ultimately it is just that: a tool.

As students begin to master certain skills, it’s ok to take scaffolding away. In fact, you should to build student independence.

As a freshman, students might need a very structured framework for a five-paragraph essay. They’ll need to almost be told what to include in each and every sentence.

But by senior year, students should be able to choose different outline styles. They might be able to choose how they approach the writing process or structure the final draft. Capable students could even be given the choice about whether or not an essay is the best way for them to show what they know!

Like real-life scaffolding, it should be temporary . A building should not rely on its scaffolding to stand up forever–neither should students.

I hope that you’ve found these scaffolding techniques helpful. Scaffolding is an important tool for differentiation and is a must in any writing curriculum.

There are so many ways to help students craft their writing: showing them a framework or writing process, giving them graphic organizers, or even just showing some great examples.

You can also help their confidence by activating prior knowledge and encourage them to help one another.

Once you start thinking about incorporating different scaffolding techniques into writing instruction, it gets easier. You’ll see opportunities everywhere to help your students craft their next masterpiece!

Was this article helpful? Get updates on blog posts like this, useful high school English resources, and all kinds of teacher tips by signing up for the It’s Lit Teaching Newsletter!

Grab a FREE Copy of Must-Have Classroom Library Title!

Sign-up for a FREE copy of my must-have titles for your classroom library and regular updates to It’s Lit Teaching! Insiders get the scoop on new blog posts, teaching resources, and the occasional pep talk!

Marketing Permissions

I just want to make sure you’re cool with the things I may send you!

By clicking below to submit this form, you acknowledge that the information you provide will be processed in accordance with our Privacy Policy.

You have successfully joined our subscriber list.

Scaffolding the Writing Process: An Approach to Assignment Design in the SOSC Core

By Sarah Johnson, Assistant Senior Instructional Professor & Director of Undergraduate Studies in Laws, Letters, and Society and CCTL Associate Pedagogy Fellow

Every time I design a new course, I return to the most significant piece of advice that I received when I was getting ready to teach for the first time: that it is my job to prepare my students to succeed on the assignments I give them. When I first heard this, it struck me as an obvious responsibility but also one that I had hardly considered. I was a graduate student at the time who was about to teach a section of Classics of Social and Political Thought in the Social Sciences (SOSC) Core along with a political theory seminar of my own design. These were courses in which students would read books, talk about them, and then write about them. I realized, on reflection, that I had assumed that my students would simply learn by doing, or that with the opportunity to read, discuss, and write that I was giving them—and with some feedback from me along the way—they would leave my classes more adept at these tasks than they were when the classes began. I had thus intended to rely upon my students’ other teachers to shape them into the kinds of readers, interlocutors, and writers that I both needed and wanted them to be and had no concrete strategy for taking on that responsibility myself. What would effective teaching moments look like in the kinds of courses that I wanted to offer? I’ve spent the last fifteen years trying to answer this question, largely through experimentation in the classroom and by learning from my own teachers and colleagues.

Below I share an approach to designing writing assignments that came together when I was teaching full time in the SOSC Core as a Harper-Schmidt Fellow. It prepares students to succeed on their SOSC essays by breaking down the writing process into the essential steps that college-level writing demands and giving students time to attend to each one. The aim of scaffolding the writing process in this way is to help students not only to practice but also to learn the necessity and value of tasks such as exploratory writing, refining their ideas in conversation with others, and being mindful of their own development as writers (and thinkers). Using this assignment for the first essay of the quarter or year also helps me to clarify what I expect from my students each time they write a paper, even when some of the steps aren’t formally assigned. The ultimate goal of the assignment is to cultivate in my students a way of thinking about and approaching the writing process that will provide a foundation for further growth in other contexts.

Two Preparatory Assignments: Exploration and Framework

I give students their essay assignment about two and a half weeks before the deadline and structure this time to help them use it effectively. There are various ways of doing this. One approach that I learned from Kristen Brookes, a former colleague who teaches at the Amherst College Writing Center, is to give students an opportunity to use informal, exploratory writing to generate ideas for a paper immediately after receiving the assignment. Following Kristen’s model, I first ask my students to revisit the material they will be writing about and to copy down about five passages that they think can help them to answer the essay question. They bring these passages to our next class, where I give them time to hand-write in short bursts of three to five minutes in response to a series of prompts. After initially writing about their tentative argument for the paper, the students engage with each of their chosen passages in whatever way is most useful to them—for example, by explaining its meaning or why they think it will be useful, or by writing about any questions the passage inspires. As I learned from Kristen, what matters most in this exercise is that the students write constantly during their brief time with each prompt and resist the urge to criticize or edit what they have written. The point of an exercise like this is to get all their ideas onto the page without judgment. Once that is done, they can spend time reviewing what they have written to determine which ideas are more and less useful and revisit their plans for their paper.

My students then take advantage of the momentum generated by this initial exercise as they complete a second preparatory assignment that is due roughly twelve days before the essay deadline. The students’ task here is to transform their initial ideas into a framework for their paper. This framework includes a draft thesis-statement followed by a point-based outline, in which they write out the point of each paragraph in a complete sentence. As a final component of the framework assignment, I ask the students to provide a few pieces of textual evidence that can be analyzed to substantiate each point along with a brief discussion of why each passage will be helpful.

I saw Kristen make great use of pairing exploratory writing and point-based outline assignments at Amherst, but it was while training to be a lector for the Academic and Professional Writing course here at Chicago in graduate school that I first learned the value of teaching students to think about paragraphs in terms of points as opposed to topics or topic sentences. Whereas a topic sentence need only announce in broad terms what each paragraph will discuss, a paragraph’s point announces to the reader the reason why that paragraph exists at all. It is the specific step in the paper’s overarching argument that a given paragraph will develop and defend in order to develop and defend that larger argument successfully. Within a paragraph, then, the point carries the authority of a thesis: it governs everything that is written in it and helps the writer to determine what they must accomplish before moving on to the next paragraph. The framework assignment thus allows students to begin considering the moves they will need to make in their paper, the order in which those moves must be made, and the kinds of evidence and analysis that they might provide to execute those moves effectively. The assignment requires much of the reading and thinking effort that a full draft would require, but by producing just its essential components a student can more easily see the relationships among their thesis and their paragraphs and where things may have gone wrong as they worked up their argument.

Required Meeting: Feedback and Refining Ideas

I use these two preparatory assignments as the basis for a twenty-minute conversation with each student one week to ten days before the essay is due. The purpose of requiring students to meet with me at this stage is not only to provide verbal feedback on their framework assignment and to address questions and concerns about their developing paper. Its purpose is also to help students make the most of their discoveries from the preparatory assignments and to demonstrate the role of conversation in the refinement and generation of ideas.

For instance, when reviewing the framework assignment, I might see that a student’s points develop a different and stronger argument than is found in the thesis statement at the top of the page. In this case, I would use our conversation to explain the misalignment between the existing thesis and points, to show the student the insight that they reached through the process of working on their paper, and to brainstorm with the student what a thesis statement might look like that would do justice to their insight. Another student might plan to discuss an important concept in their paper without doing so in sufficient detail. Here I would ask the student to explain their understanding of the concept in order to draw out the knowledge they have about it that does not yet appear in their framework. We could then discuss how to incorporate that information into their paper.

Reflection: Opening a Conversation about Writing

Just as the required meeting offers students a chance to step back from their ideas in the middle of the writing process to reflect on the shape their paper is taking, I give students a way to take stock of their entire experience of writing the paper after they finish it. I want them to keep in mind that the paper they have written for me is part of their larger process of development as writers, a process that began long before they entered my classroom and one that will continue long after they leave. This means that when they write for me, they are drawing upon habits and skills that they learned by writing in other contexts while also cultivating new habits and skills that they can rely upon in future papers. Before submitting their final drafts, my students therefore prepare a 300- to 500-word reflection that helps them to understand their own writing process and to become more self-conscious about their development as writers. These reflections discuss 1) what they found most challenging about writing the essay; 2) something that they learned while writing it; 3) something that their essay does well; and 4) something that they could do to improve the essay. When they write their final paper of the quarter, I also ask them to discuss 5) how they have improved as a writer during the quarter; and 6) in what ways they would like to improve as a writer in future quarters.

Final Paper Comments: A Focus on Writing Development

The students’ reflections on their papers open a conversation about writing that I enter through my feedback. I typically begin my comments at the end of a paper by engaging with one of their own observations about their writing process. For example, students often report that their argument underwent significant changes between the time they began outlining and drafting their paper and when they submitted it. Some will take from this experience the insight that they need to try to give themselves more time than they typically do to write their papers as these transformations, although frustrating, ultimately made their final draft much better than it would have otherwise been. In response to an observation like this, I might explain that this is indeed an indispensable part of the writing process and that building in more time for these discoveries and revisions will help them to write at an even higher level. But some students will draw a different conclusion from the same experience, namely that they did something wrong because they did not begin writing with the best possible argument in mind. Their goal in future essays is usually to develop a better plan for their papers in advance so that they can avoid friction and uncertainty in the drafting process. In these cases, I would caution them against this aspiration by explaining that we typically only find the best arguments we can make through the process of writing itself, and that the evolution of their own argument demonstrates that they did exactly what they were supposed to do during the writing process.

In the rest of my comments, I discuss two or three writing issues that I want the student to try to address in their next paper. I number these discussions and place corresponding numbers in the margins of the essay to show the student where each problem occurred. Over the years, these numbers have become the only margin notes I make on essays, an approach that I remember one of my own professors, Aryeh Kosman, using when I was in college. I have discovered that providing feedback in this way allows me to focus the student’s attention on making the improvements that I think will have the greatest impact on the next paper they write, whether that paper is written for me or another instructor. And by addressing these at the end of the paper, I give myself the space both to explain why the issues I identified are indeed problems and to provide concrete suggestions for how to avoid them in the future. In doing so, I often draw upon my training for Academic and Professional Writing, where I was taught to rewrite sentences for my students in order to show them how the feedback I was offering could be put to use and the difference that it would make to their writing.

Although this kind of feedback necessarily emphasizes problems at the level of writing over problems at the level of textual interpretation, this does not mean that I ignore the claims my students make about the texts we are studying. Rather, it means that what I say about a student’s interpretation will be in the service of helping them to do a better job on their next paper, which is unlikely to be on the same text and will often be in another course altogether. For example, students often attribute ideas to an author that I don’t think can be supported by the text at all, and certainly not by the parts of it that they quoted or cited as evidence. When this happens, I might explain why I don’t think they can use a particular passage as evidence for their claim, offer a few examples of claims that the passage could in fact support, and explain the difference between these claims and the student’s. My aim in doing this would be to help the student to become a more careful reader by giving them tools that can help them to scrutinize their textual evidence during the drafting process.

Final Thoughts

While this specific approach to scaffolding writing assignments can help students to succeed on their SOSC essays, the principle that underlies it—breaking down a writing process into its essential components—can also guide the design of writing assignments in upper-level undergraduate courses. It has helped me, for example, when designing research assignments for my courses in the Law, Letters, and Society program. I ask myself what students would have to accomplish throughout the quarter to succeed on their projects and turn these expected milestones into guided assignments that provide an opportunity for feedback. No matter the level of the course, then, I aim to avoid assuming that my students already know the motions that I expect them to go through to complete an assignment and instead build those into the course itself.

Sarah Johnson is Assistant Senior Instructional Professor and Director of Undergraduate Studies in the Law, Letters, and Society (LLSO) Program. Her current research focuses on the coevolution of Karl Marx’s ideas about history, critique, and political economy in the 1840s. In addition to teaching courses on political economy in LLSO, she regularly teaches in the Classics of Social and Political Thought Core sequence.

Select a year to see courses

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

- OC Test Preparation

- Selective School Test Preparation

- Maths Acceleration

- English Advanced

- Maths Standard

- Maths Advanced

- Maths Extension 1

- English Standard

- Maths Extension 2

Get HSC exam ready in just a week

- UCAT Exam Preparation

Select a year to see available courses

- English Units 1/2

- Maths Methods Units 1/2

- Biology Units 1/2

- Chemistry Units 1/2

- Physics Units 1/2

- English Units 3/4

- Maths Methods Units 3/4

- Biology Unit 3/4

- Chemistry Unit 3/4

- Physics Unit 3/4

- UCAT Preparation Course

- Matrix Learning Methods

- Matrix Term Courses

- Matrix Holiday Courses

- Matrix+ Online Courses

- Campus overview

- Castle Hill

- Strathfield

- Sydney City

- Year 3 NAPLAN Guide

- OC Test Guide

- Selective Schools Guide

- NSW Primary School Rankings

- NSW High School Rankings

- NSW High Schools Guide

- ATAR & Scaling Guide

- HSC Study Planning Kit

- Student Success Secrets

- Reading List

- Year 6 English

- Year 7 & 8 English

Year 9 English

- Year 10 English

- Year 11 English Standard

- Year 11 English Advanced

- Year 12 English Standard

- Year 12 English Advanced

- HSC English Skills

- How To Write An Essay

- How to Analyse Poetry

- English Techniques Toolkit

- Year 7 Maths

- Year 8 Maths

- Year 9 Maths

- Year 10 Maths

- Year 11 Maths Advanced

- Year 11 Maths Extension 1

- Year 12 Maths Standard 2

- Year 12 Maths Advanced

- Year 12 Maths Extension 1

- Year 12 Maths Extension 2

Science guides to help you get ahead

- Year 11 Biology

- Year 11 Chemistry

- Year 11 Physics

- Year 12 Biology

- Year 12 Chemistry

- Year 12 Physics

- Physics Practical Skills

- Periodic Table

- VIC School Rankings

- VCE English Study Guide

- Set Location

- 1300 008 008

- 1300 634 117

Welcome to Matrix Education

To ensure we are showing you the most relevant content, please select your location below.

How To Do Essay Scaffolding Drills And Boost Your Essay Marks

Get free study tips and resources delivered to your inbox.

Join 75,893 students who already have a head start.

" * " indicates required fields

You might also like

- How to Write a Scientific Report | Step-by-Step Guide

- Top Study Tips From Matrix Tutors

- 2021 HSC Maths Standard 2 Exam Paper Solutions

- Mary’s Hacks: How I Topped the State in HSC Mathematics

- Rachel’s Hacks: My Gap Year Experience

Related courses

Year 7 english, year 8 english.

Are you not getting the essay marks you want or need? Do you not have the time to write a whole practice essay but need to improve your essay writing skills? Well, essay scaffolding drills are the solution for you!!!

How to do essay scaffolding drills and boost your essay marks

It doesn’t matter if you’re in year 7 facing down your yearly exams or are in Year 12 and are days away from Paper 1, you still need to practise essay writing if you want to improve. But that means investing time, a precious and limited resource.

But, if you want to boost your essay marks, practise you must!

But what should you do if you don’t have an hour or more spare to write that practice essay? Do essay scaffolding drills!

In this how-to, we’re going to discuss

- What a scaffolding drill is

- What’s in scaffolding drills

- Unpack the question

- Thesis statement

- Thematic framework

- Module or Linking statement

- Topic sentences

- What to do next!

What is a scaffolding drill?

A scaffolding drill is where you plan out your entire essay and write an introduction under timed condition – 10 minutes !

This practice trains you to gather your thoughts, formulate ideas quickly, and get them on to paper – just as you must in an exam!

Scaffolding drills are the equivalent of a movie montage, they help you prepare for exam day in short chunks!

Scaffolding drills aren’t a substitute for writing practice essays, but they are an excellent supplement! You should aim complete scaffold drills throughout the term. Ideally, you should be doing them at least once a week, and slowly ramping up when you are nearing your exam period.

A good schedule might be to do 2 per session, to different questions, 2-3 times a week. This way, you work on developing a sustained argument and putting together a good introduction consistently a couple of times a week in less time than a round of Fortnite.

What’s in a scaffolding drill:

To do a scaffold drill, you must:

- Write your thesis statement

- Write your thematic framework

- Write a linking/module statement

- Write your topic sentences for your body paragraphs

- And, if you’ve time left on the clock) list some evidence for each body paragraph

As you can see, this a challenging amount to get done in a small amount of time – an introduction and essay plan! But this is a great way to simulate exam conditions and help you get used to thriving under exam pressure!

What we’ll do now is break down how to do a scaffolding drill, step-by-step and show you how to do them.

How to do scaffolding drills, step-by-step

Okay, let’s break down these steps in greater detail and guide you through an example. This will help you understand the process in a practical and detailed manner. Depending on what you prefer, you can either watch our video, or read the guide below!

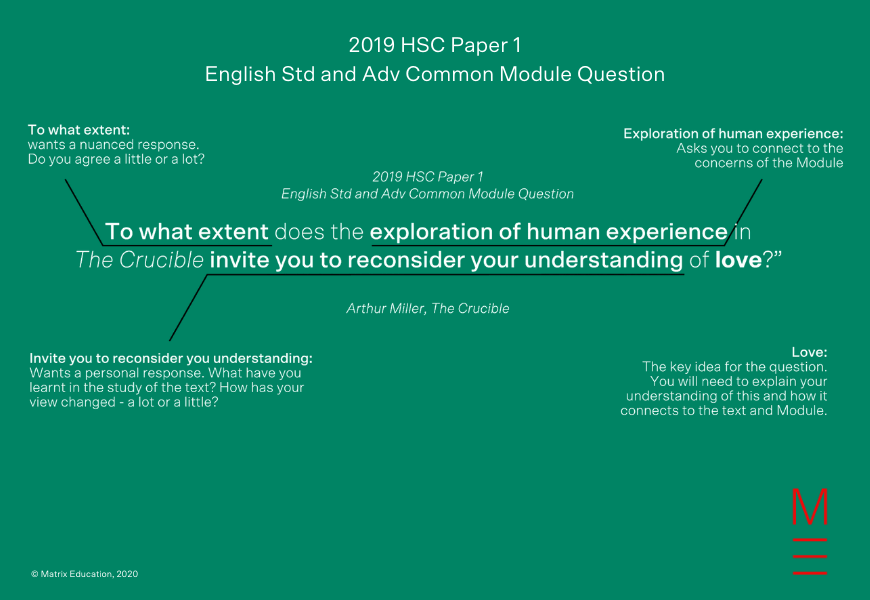

First, let’s pick an example question. For this demo, we’ll use the 2019 HSC Paper 1 Common Module Essay Question:

Step 1 – Unpack the question

The first step is to unpack the question and make sure you know what you’re answering!

The most common problems students have with writing essays, especially during exams, is not answering the question that’s been asked! Why? Students don’t answer the question because they’re regurgitating a memorised essay.

It is crucial that you are reading your questions and anwering it properly.

The only way of ensuring that you understand what the question requires you to do is to unpack it.

This is the first step of your scaffolding drills.

To do this, you need to identify the following components of the question:

- Key verbs : What are the instructional words in the question? What are they asking you to do?

- Keywords : What are the central nouns? What are you being asked to investigate?

- Themes and ideas : What ideas or themes from the text are you being asked to investigate?

Note: If you want to learn how to properly answer different NESA key verbs, then take a read of our How to Respond to NESA Key Words to Ace Your HSC .

So our question was:

To what extent does the exploration of human experience in The Crucible invite you to reconsider your understanding of love?

Let’s unpack this:

In short, unpacking the key terms gives us –

- To what extent – wants a nuanced response. Do you agree a little or a lot?

- Exploration of human experience – Asks you to connect to the concerns of the Module.

- Invite you to reconsider your understanding – Wants a personal response. What have you learnt in the study of the text? How has your view changed – a lot or a little?

- Love – The key idea for the question. You will need to explain your understanding of this and how it connects to the text and Module.

Now we’re done with unpacking the question, let’s see how to craft an introduction:

- Thesis – Answer to the question

- Thematic framework – Supporting arguments to your thesis

- Module/linking statement – summation of intro and connection to Module or mode of study.

Step 2 – Introduction: Thesis statement

Now, you need to figure out a thesis statement. Your thesis is, first and foremost, your answer to the question!

A thesis statement should be 1-2 sentences. A 2 sentence thesis statement is good as it allows you to make a broad conceptual argument before drilling down into something more detailed.

Let’s see what that looks like.

Love is a multifaceted and universal emotion sought after by all of us. Arthur Miller’s tragedy The Crucible is a powerful depiction of a town turning against itself that compels us to evaluate love and what we will do in pursuit of it or driven by it.

This is a “double-barrelled” thesis statement as it gives a detailed answer in two parts.

- The 1st sentence focuses on the Module -Common Module: Texts and Human Experiences – key ideas and responds to the question

- The 2nd sentence drills into the question. it introduces the text and digs into the key ideas from the text.

This approach enables you to give a sophisticated and detailed thesis that is also direct and clear. It both frames and elaborates on your argument.

Step 3 – Introduction: Thematic framework

The thematic framework is where you introduce the supporting argument for your thesis. here, you outline themes and ideas you will use in support of your argument.

This needs to be between 2-3 sentences, but, ideally, no more than 1 sentence each.

This is an essential part of a sustained argument as it introduces the signposting the reader needs to make sense of your argument as it develops throughout your essay.

Let’s see what this looks like in response to the question we’re considering.

In our thematic framework, we need to discuss 3 different ways Miller has represented love in The Crucible :

- Miller illustrates the paradox of how good intentions driven by love can lead to tragedy as Elizabeth and Hale’s actions cause harm, not good

- In contrast, Miller explores how hypocritical actions pursued under the veneer of love are often driven by anger or avarice as Abigail and Parris’ actions divide and devastated the town

- Ultimately, the way the remains of the community tries to rally around the individuals facing down Danforth’s corrupt court reveals how love is a powerful unifying force

As you can see, these ideas develop on our thesis and lay a clear framework for the argument that will follow. We will echo these directly in our topic sentences. This will signpost to the reader where they are in the argument.

Remember, most readers aren’t as good as remembering information as they think, signposting is essential to help them orientate themselves in your argument.

Now we’ve laid the foundations for our essay, let’s connect it back to the mode of study, in this case, the Common Module.

Step 4 – Introduction: Linking/Module statement

The linking or Module statement will connect your thesis and supporting arguments to the Module or focus of your study in class.

This will begin to demonstrate your mastery of the topic you’ve been studying at school!

The Common Module: Texts and Human Experiences is concerned with exploring the emotions and relationships key to being human. Our statement needs to reflect these concerns and respond to the question.

Let’s take a gander at an example.

Viewing and engaging with powerful literary works forces us to reflect on what makes us human and reevaluate what we know about key human emotions, such as love.

As you can see, this final statement connects everything we’ve discussed. It links our unpacking of love, summarises our approach to the question, and begins developing a personal response with the first person plural pronouns – “us” and “we.”

Whenever you craft a linking statement, aim to summarise the argument concisely and clearly.

Now, we’ve put together our sophisticated introduction, we need to draft the topic sentences to accompany it.

Step 5 – Body: Draft topic sentences

Whenever writing time starts in an exam, it will be to your benefit if you plan your essay AND draft your topic sentences. This means that when you begin writing your body, you can refine what you’ve already developed – ensuring that you’ll get better marks.

Topic sentences an essential part of a sustained argument.

Topic sentences connect directly to the ideas introduced in the introduction!

In essence, they say to the reader: “Hey, remember that thing I said I was going to talk about? This is where I am going to talk about it!” This will help inculcate your argument and persuade the reader.

Topic sentences need to be concise and reflect both your thesis and the ideas that you introduced in the thematic framework.

Let’s take a look at ours:

- Topic sentence 1: Good intentions motivated by love can have paradoxically negative outcomes.

- Topic sentence 2: Individuals will act under the charade of love, but their true emotional motivations have divisive consequences.

- Topic sentence 3: Love is strongest as a unifying emotion as individuals and communities rally behind and support one another.

As you can see, these reintroduce the ideas from our thematic framework and signal how we will use them to support our argument. This means that we’ve developed the scaffold for a sustained argument in our essay!

Now, you’ve got the framework for an essay. But, how are you going for time? Do you have a few minutes left? Yes? Great, don’t stop now, think about some examples!

Step 6 – Body: Pick your Evidence (Optional)

This is where you see how good you are working against the clock! If you have one or two minutes left, take the opportunity to identify the quotations or examples that might best support your argument.

You don’t need to write out the whole quotation, that would be completely unfeasible given the time constraints. Buuuut, you can shorthand them to help YOU recall them.

For example, to return to the Crucible Question we could shorthand three examples for the first paragraph by jotting down:

- Elizabeth lies – “(A plea.) My husband… is a goodly man, sir… (She starts to glance at Proctor.)”

- Hale regret newlywed – “I came into this village like a bridegroom to his beloved, bearing gifts of high religion; the very crowns of holy law I brought, and what I touched with my bright confidence, it died; and where I turned the eye of my great faith, blood flowed up.”

- Hale guilt – “I would save your husband‘s life, for if he is taken I count myself his murderer.”

These short-hand prompts will help you remember and recall examples. This is a very important skill for you to develop!

What next? Practise to the clock!

Okay, so now you’ve seen how to do scaffolding drills and what they entail, you will be able to go forth and boost your exam marks.

So, what do you need to do, now? Find yourself some essay questions, grab your pen and paper, and set yourself that 10-minute timer. Go!!

Looking for some HSC practice questions, try ours:

- 20 Common Module Practice Essay Questions

- 25 Module A Textual Conversation Practice Essay Questions

- 31 Module B Practice Questions to save your HSC

Want to see how Matrix English will drill skills into you?

At Matrix+, we provide engaging Theory lessons with HSC English experts to help you consolidate your knowledge and refine your writing skills!

Get ahead with Matrix+ Online

Expert teachers, detailed feedback and one-to-one help. Learn at your own pace, wherever you are.

Written by Matrix English Team

© Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au, 2023. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Year 7 English tutoring at Matrix will help your child improve their reading and writing skills.

Learning methods available

Level 7 English tutoring program that targets analytical and writing skills.

Year 8 English tutoring at Matrix is known for helping students build strong reading and writing skills.

Year 9 English tutoring at Matrix is known for helping students build strong reading and writing skills.

Related articles

10 Calculation Questions for your Physics VCE Exam Study

Here are 10 fundamental Physics questions you need to practice before your VCE exams!

The Ultimate Guide to NESA’s Maths Reference Sheet | Overview

Did you know that you can use the NESA Maths Reference Sheet during all your Maths HSC exams? Learn how to make the most of it and test your maths skills with these sample questions and explanations!

The Top 5 Persuasive Techniques for Speeches

In this article, we will show you the top 5 techniques you must use in your speeches to wow your audience.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

This one is probably the best-known version of scaffolding for any English teacher. The writing process is basically a framework for how to write. It consists of six steps: brainstorming, outlining, creating a rough draft, evaluating that work, then sculpting a final draft, before the optional step of publishing.

Before You Start: Consider the "direction word" in the question, and what it is asking you to do. Consider the "scope" of the question, and how it will guide your research and response. Highlight the "content" words of the question, so your plan doesn't go off topic. Rewrite the question in your own words to help you understand ...

6. Quick Writes. Not every piece of writing students do has to be lengthy. In fact, quick, daily writing is an effective way for English learners to practice writing in a low-stress setting. Long essays and pages of writing can be intimidating for students who are learning the structures of the English language.

does not have to be. Scaffolding is one process that allows teachers to organize a writing activity systematically to meet the needs of all students. This Considerations Packet introduces a scaffolding approach for a typical six-step writing process that can be modified for almost all grade and ability levels. Additionally, a sample outline for ...

Scaffolding is the process of breaking down a larger writing assignment into smaller assignments that focus on the skills or types of knowledge students require to successfully complete the larger assignment. Sequencing is the process of arranging the scaffolded assignments into an order that builds towards the larger writing assignment.

Explanation - Discusses the technique used. Link - Summarises the argument the evidence is supporting and connects it to the thesis statement or topic sentence. Linking Statement - This summarises your paragraph and connects it to the rest of your essay. 3. Conclusion - A summary of your argument.

Here's a short excerpt from "They Say, I Say" (see a link earlier in this post) that Lara Hoekstra gives to students so they can use it as the "Back it Up With A Quotation" part of the ABC writing frame (or as the "Q" in the "PQC" - Make a Point, use a Quotation to back it up, and make a Comment): Nicole Simsonsen shared a ...

These reflections discuss 1) what they found most challenging about writing the essay; 2) something that they learned while writing it; 3) something that their essay does well; and 4) something that they could do to improve the essay. When they write their final paper of the quarter, I also ask them to discuss 5) how they have improved as a ...

To do a scaffold drill, you must: Unpack the question. Write your thesis statement. Write your thematic framework. Write a linking/module statement. Write your topic sentences for your body paragraphs. And, if you've time left on the clock) list some evidence for each body paragraph.

Harvard College Writing Center 5 Asking Analytical Questions When you write an essay for a course you are taking, you are being asked not only to create a product (the essay) but, more importantly, to go through a process of thinking more deeply about a question or problem related to the course. By writing about a