An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Cyberbullying Among Adolescents and Children: A Comprehensive Review of the Global Situation, Risk Factors, and Preventive Measures

Chengyan zhu, shiqing huang, richard evans.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Edited by: Daniel Bressington, Charles Darwin University, Australia

Reviewed by: Alexandra Restrepo, University of Antioquia, Colombia; Si-Tong Chen, Victoria University, Australia

*Correspondence: Wei Zhang [email protected]

This article was submitted to Public Mental Health, a section of the journal Frontiers in Public Health

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Received 2020 Nov 29; Accepted 2021 Feb 10; Collection date 2021.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

Background: Cyberbullying is well-recognized as a severe public health issue which affects both adolescents and children. Most extant studies have focused on national and regional effects of cyberbullying, with few examining the global perspective of cyberbullying. This systematic review comprehensively examines the global situation, risk factors, and preventive measures taken worldwide to fight cyberbullying among adolescents and children.

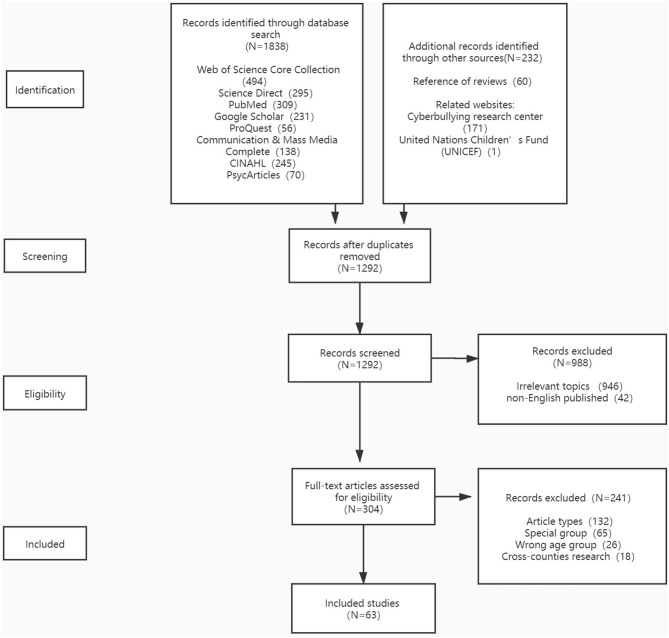

Methods: A systematic review of available literature was completed following PRISMA guidelines using the search themes “cyberbullying” and “adolescent or children”; the time frame was from January 1st, 2015 to December 31st, 2019. Eight academic databases pertaining to public health, and communication and psychology were consulted, namely: Web of Science, Science Direct, PubMed, Google Scholar, ProQuest, Communication & Mass Media Complete, CINAHL, and PsycArticles. Additional records identified through other sources included the references of reviews and two websites, Cyberbullying Research Center and United Nations Children's Fund. A total of 63 studies out of 2070 were included in our final review focusing on cyberbullying prevalence and risk factors.

Results: The prevalence rates of cyberbullying preparation ranged from 6.0 to 46.3%, while the rates of cyberbullying victimization ranged from 13.99 to 57.5%, based on 63 references. Verbal violence was the most common type of cyberbullying. Fourteen risk factors and three protective factors were revealed in this study. At the personal level, variables associated with cyberbullying including age, gender, online behavior, race, health condition, past experience of victimization, and impulsiveness were reviewed as risk factors. Likewise, at the situational level, parent-child relationship, interpersonal relationships, and geographical location were also reviewed in relation to cyberbullying. As for protective factors, empathy and emotional intelligence, parent-child relationship, and school climate were frequently mentioned.

Conclusion: The prevalence rate of cyberbullying has increased significantly in the observed 5-year period, and it is imperative that researchers from low and middle income countries focus sufficient attention on cyberbullying of children and adolescents. Despite a lack of scientific intervention research on cyberbullying, the review also identified several promising strategies for its prevention from the perspectives of youths, parents and schools. More research on cyberbullying is needed, especially on the issue of cross-national cyberbullying. International cooperation, multi-pronged and systematic approaches are highly encouraged to deal with cyberbullying.

Keywords: cyberbullying, children, adolescents, globalization, risk factors, preventive measures

Introduction

Childhood and adolescence are not only periods of growth, but also of emerging risk taking. Young people during these periods are particularly vulnerable and cannot fully understand the connection between behaviors and consequences ( 1 ). With peer pressures, the heat of passion, children and adolescents usually perform worse than adults when people are required to maintain self-discipline to achieve good results in unfamiliar situations. Impulsiveness, sensation seeking, thrill seeking, and other individual differences cause adolescents to risk rejecting standardized risk interventions ( 2 ).

About one-third of Internet users in the world are children and adolescents under the age of 18 ( 3 ). Digital technology provide a new form of interpersonal communication ( 4 ). However, surveys and news reports also show another picture in the Internet Age. The dark side of young people's internet usage is that they may bully or suffer from others' bullying in cyberspace. This behavior is also acknowledged as cyberbullying ( 5 ). Based on Olweus's definition, cyberbullying is usually regarded as bullying implemented through electronic media ( 6 , 7 ). Specifically, cyberbullying among children and adolescents can be summarized as the intentional and repeated harm from one or more peers that occurs in cyberspace caused by the use of computers, smartphones and other devices ( 4 , 8 – 12 ). In recent years, new forms of cyberbullying behaviors have emerged, such as cyberstalking and online dating abuse ( 13 – 15 ).

Although cyberbullying is still a relatively new field of research, cyberbullying among adolescents is considered to be a serious public health issue that is closely related to adolescents' behavior, mental health and development ( 16 , 17 ). The increasing rate of Internet adoption worldwide and the popularity of social media platforms among the young people have worsened this situation with most children and adolescents experiencing cyberbullying or online victimization during their lives. The confines of space and time are alleviated for bullies in virtual environments, creating new venues for cyberbullying with no geographical boundaries ( 6 ). Cyberbullying exerts negative effects on many aspects of young people's lives, including personal privacy invasion and psychological disorders. The influence of cyberbullying may be worse than traditional bullying as perpetrators can act anonymously and connect easily with children and adolescents at any time ( 18 ). In comparison with traditional victims, those bullied online show greater levels of depression, anxiety and loneliness ( 19 ). Self-esteem problems and school absenteeism have also proven to be related to cyberbullying ( 20 ).

Due to changes in use and behavioral patterns among the youth on social media, the manifestations and risk factors of cyberbullying have faced significant transformation. Further, as the boundaries of cyberbullying are not limited by geography, cyberbullying may not be a problem contained within a single country. In this sense, cyberbullying is a global problem and tackling it requires greater international collaboration. The adverse effects caused by cyberbullying, including reduced safety, lower educational attainment, poorer mental health and greater unhappiness, led UNICEF to state that “no child is absolutely safe in the digital world” ( 3 ).

Extant research has examined the prevalence and risk factors of cyberbullying to unravel the complexity of cyberbullying across different countries and their corresponding causes. However, due to variations in cyberbullying measurement and methodologies, no consistent conclusions have been drawn ( 21 ). Studies into inconsistencies in prevalence rates of cyberbullying, measured in the same country during the same time period, occur frequently. Selkie et al. systematically reviewed cyberbullying among American middle and high school students aged 10–19 years old in 2015, and revealed that the prevalence of cyberbullying victimization ranged from 3 to 72%, while perpetration ranged from 1 to 41% ( 22 ). Risk and protective factors have also been broadly studied, but confirmation is still needed of those factors which have more significant effects on cyberbullying among young people. Clarification of these issues would be useful to allow further research to recognize cyberbullying more accurately.

This review aims to extend prior contributions and provide a comprehensive review of cyberbullying of children and adolescents from a global perspective, with the focus being on prevalence, associated risk factors and protective factors across countries. It is necessary to provide a global panorama based on research syntheses to fill the gaps in knowledge on this topic.

Search Strategies

This study strictly employed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. We consulted eight academic databases pertaining to public health, and communication and psychology, namely: Web of Science, Science Direct, PubMed, Google Scholar, ProQuest, Communication & Mass Media Complete, CINAHL, and PsycArticles. Additional records identified through other sources included the references of reviews and two websites, Cyberbullying Research Center and United Nations Children's Fund. With regard to the duration of our review, since most studies on cyberbullying arose around 2015 ( 9 , 21 ), this study highlights the complementary aspects of the available information about cyberbullying during the recent 5 year period from January 1st, 2015 to December 31st, 2019.

One researcher extracted keywords and two researchers proposed modifications. We used two sets of subject terms to review articles, “cyberbullying” and “child OR adolescent.” Some keywords that refer to cyberbullying behaviors and young people are also included, such as threat, harass, intimidate, abuse, insult, humiliate, condemn, isolate, embarrass, forgery, slander, flame, stalk, manhunt, as well as teen, youth, young people and student. The search formula is (cyberbullying OR cyber-bullying OR cyber-aggression OR ((cyber OR online OR electronic OR Internet) AND (bully * OR aggres * OR violence OR perpetrat * OR victim * OR threat * OR harass * OR intimidat * OR * OR insult * OR humiliate * OR condemn * OR isolate * OR embarrass * OR forgery OR slander * OR flame OR stalk * OR manhunt))) AND (adolescen * OR child OR children OR teen? OR teenager? OR youth? OR “young people” OR “elementary school student * ” OR “middle school student * ” OR “high school student * ”). The main search approach is title search. Search strategies varied according to the database consulted, and we did not limit the type of literature for inclusion. Journals, conference papers and dissertations are all available.

Specifically, the inclusion criteria for our study were as follows: (a). reported or evaluated the prevalence and possible risk factors associated with cyberbullying, (b). respondents were students under the age of 18 or in primary, junior or senior high schools, and (c). studies were written in English. Exclusion criteria were: (a). respondents came from specific groups, such as clinical samples, children with disabilities, sexual minorities, specific ethnic groups, specific faith groups or samples with cross-national background, (b). review studies, qualitative studies, conceptual studies, book reviews, news reports or abstracts of meetings, and (c). studies focused solely on preventive measures that were usually meta-analytic and qualitative in nature. Figure 1 presents the details of the employed screening process, showing that a total of 63 studies out of 2070 were included in our final review.

PRISMA flow chart diagram showing the process of study selection for inclusion in the systematic review on children and adolescents cyberbullying.

Meta-analysis was not conducted as the limited research published within the 5 years revealed little research which reported odds ratio. On the other hand, due to the inconsistency of concepts, measuring instruments and recall periods, considerable variation could be found in research quality ( 23 ). Meta-analysis is not a preferred method.

Coding Scheme

For coding, we created a comprehensive code scheme to include the characteristics. For cyberbullying, we coded five types proposed by Willard ( 24 – 26 ), which included verbal violence, group violence, visual violence, impersonating and account forgery, and other behaviors. Among them, verbal violence is considered one of the most common types of cyberbullying and refers to the behavior of offensive responses, insults, mocking, threats, slander, and harassment. Group violence is associated with preventing others from joining certain groups or isolating others, forcing others to leave the group. Visual violence relates to the release and sharing of embarrassing photos and information without the owners' consent. Impersonating and account forgery refers to identity theft, stealing passwords, violating accounts and the creation of fake accounts to fraudulently present the behavior of others. Other behaviors include disclosure of privacy, sexual harassment, and cyberstalking. To comprehensively examine cyberbullying, we coded cyberbullying behaviors from both the perspectives of cyberbullying perpetrators and victims, if mentioned in the studies.

In relation to risk factors, we drew insights from the general aggression model, which contributes to the understanding of personal and situational factors in the cyberbullying of children and adolescents. We chose the general aggression model because (a) it contains more situational factors than other models (e.g., social ecological models) - such as school climate ( 9 ), and (b) we believe that the general aggression model is more suitable for helping researchers conduct a systematic review of cyberbullying risk and protective factors. This model provides a comprehensive framework that integrates domain specific theories of aggression, and has been widely applied in cyberbullying research ( 27 ). For instance, Kowalski and colleagues proposed a cyberbullying encounter through the general aggression model to understand the formation and development process of youth cyberbullying related to both victimization and perpetration ( 9 ). Victims and perpetrators enter the cyberbullying encounter with various individual characteristics, experiences, attitudes, desires, personalities, and motives that intersect to determine the course of the interaction. Correspondingly, the antecedents pertaining to cyberbullying are divided into two broad categories, personal factors and situational factors. Personal factors refer to individual characteristics, such as gender, age, motivation, personality, psychological states, socioeconomic status and technology use, values and perceptions, and other maladaptive behaviors. Situational factors focus on the provocation/support, parental involvement, school climate, and perceived anonymity. Consequently, our coders related to risk factors consisting of personal factors and situational factors from the perspectives of both cyberbullying perpetrators and victims.

We extracted information relating to individual papers and sample characteristics, including authors, year of publication, country, article type, sampling procedures, sample characteristics, measures of cyberbullying, and prevalence and risk factors from both cyberbullying perpetration and victimization perspectives. The key words extraction and coding work were performed twice by two trained research assistants in health informatics. The consistency test results are as follows: the Kappa value with “personal factors” was 0.932, and the Kappa value with “situational factors” was 0.807. The result shows that the coding consistency was high enough and acceptable. Disagreements were resolved through discussion with other authors.

Quality Assessment of Studies

The quality assessment of the studies is based on the recommended tool for assessing risk of bias, Cochrane Collaboration. This quality assessment tool focused on seven items: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other sources of bias ( 28 ). We assessed each item as “low risk,” “high risk,” and “unclear” for included studies. A study is considered of “high quality” when it meets three or more “low risk” requirements. When one or more main flaw of a study may affect the research results, the study is considered as “low quality.” When a lack of information leads to a difficult judgement, the quality is considered to be “unclear.” Please refer to Appendix 1 for more details.

This comprehensive systematic review comprised a total of 63 studies. Appendices 2 , 3 show the descriptive information of the studies included. Among them, 58 (92%) studies measured two or more cyberbullying behavior types. The sample sizes of the youths range from several hundred to tens of thousands, with one thousand to five thousand being the most common. As for study distribution, the United States of America, Spain and China were most frequently mentioned. Table 1 presents the detail.

Descriptive information of studies included (2015–2019).

Prevalence of Global Cyberbullying

Prevalence across countries.

Among the 63 studies included, 22 studies reported on cyberbullying prevalence and 20 studies reported on prevalence from victimization and perpetration perspectives, respectively. Among the 20 studies, 11 national studies indicated that the prevalence of cyberbullying victimization and cyberbullying perpetration ranged from 14.6 to 52.2% and 6.3 to 32%, respectively. These studies were conducted in the United States of America ( N = 4) ( 29 – 32 ), South Korea ( N = 3) ( 33 – 35 ), Singapore ( N = 1) ( 36 ), Malaysia ( N = 1) ( 37 ), Israel ( N = 1) ( 38 ), and Canada ( N = 1) ( 39 ). Only one of these 11 national studies is from an upper middle income country, and the rest are from highincome countries identified by the World Bank ( 40 ). By combining regional and community-level studies, the prevalence of cyberbullying victimization and cyberbullying perpetration ranged from 13.99 to 57.5% and 6.0 to 46.3%, respectively. Spain reported the highest prevalence of cyberbullying victimization (57.5%) ( 41 ), followed by Malaysia (52.2%) ( 37 ), Israel (45%) ( 42 ), and China (44.5%) ( 43 ). The lowest reported victim rates were observed in Canada (13.99%) and South Korea (14.6%) ( 34 , 39 ). The reported prevalence of cyberbullying victimization in the United States of America ranged from 15.5 to 31.4% ( 29 , 44 ), while in Israel, rates ranged from 30 to 45% ( 26 , 42 ). In China, rates ranged from 6 to 46.3% with the country showing the highest prevalence of cyberbullying perpetration (46.30%) ( 15 , 43 , 45 , 46 ). Canadian and South Korean studies reported the lowest prevalence of cyberbullying perpetration at 7.99 and 6.3%, respectively ( 34 , 39 ).

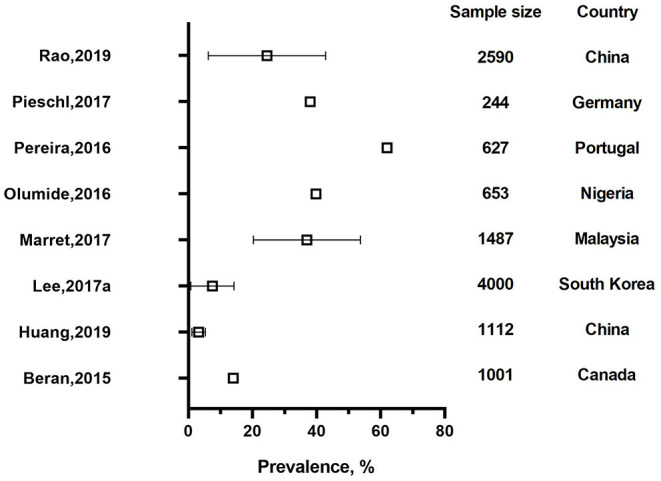

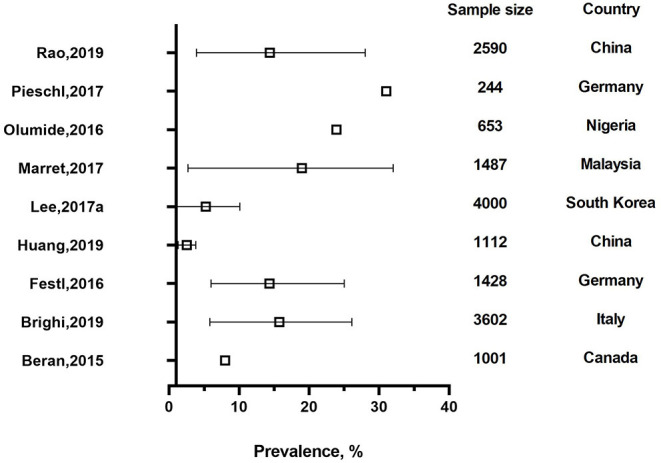

A total of 10 studies were assessed as high quality studies. Among them, six studies came from high income countries, including Canada, Germany, Italy, Portugal, and South Korea ( 13 , 34 , 39 , 46 – 48 ). Three studies were from upper middle income countries, including Malaysia and China ( 37 , 43 ) and one from a lower middle income country, Nigeria ( 49 ). Figures 2 , 3 describe the prevalence of cyberbullying victimization and perpetration respectively among high quality studies.

The prevalence of cyberbullying victimization of high quality studies.

The prevalence of cyberbullying perpetration of high quality studies.

Prevalence of Various Cyberbullying Behaviors

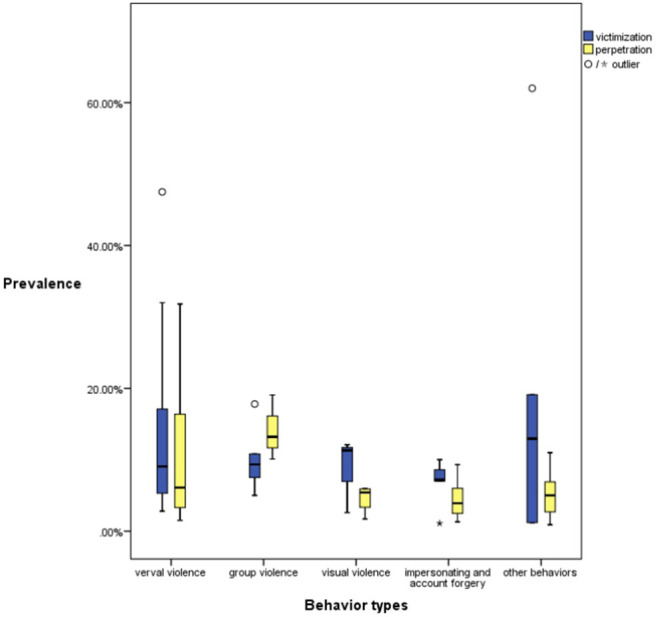

For the prevalence of cyberbullying victimization and perpetration, the data were reported in 18 and 14 studies, respectively. Figure 4 shows the distribution characteristics of the estimated value of prevalence of different cyberbullying behaviors with box plots. The longer the box, the greater the degree of variation of the numerical data and vice versa. The rate of victimization and crime of verbal violence, as well as the rate of victimization of other behaviors, such as cyberstalking and digital dating abuse, has a large degree of variation. Among the four specified types of cyberbullying behaviors, verbal violence was regarded as the most commonly reported behaviors in both perpetration and victimization rates, with a wide range of prevalence, ranging from 5 to 18%. Fewer studies reported the prevalence data for visual violence and group violence. Studies also showed that the prevalence of impersonation and account forgery were within a comparatively small scale. Specific results were as follows.

Cyberbullying prevalence across types (2015–2019).

Verbal Violence

A total of 13 studies reported verbal violence prevalence data ( 15 , 26 , 34 , 37 – 39 , 42 , 43 , 47 , 48 , 50 , 51 ). Ten studies reported the prevalence of verbal violence victimization ranging from 2.8 to 47.5%, while seven studies claimed perpetration prevalence ranging from 1.5 to 31.8%. Malaysia reported the highest prevalence of verbal violence victimization (47.5%) ( 37 ), followed by China (32%) ( 43 ). China reported that the prevalence of verbal violence victimization ranged from 5.1 to 32% ( 15 , 43 ). Israel reported that the prevalence of verbal violence victimization ranged from 3.4 to 18% ( 26 , 38 , 42 ). For perpetration rate, Malaysia reported the highest level at 31.8% ( 37 ), while a study for Spain reported the lowest, ranging from 3.2 to 6.4% ( 51 ).

Group Violence

The prevalence of group violence victimization was explored within 4 studies and ranged from 5 to 17.8% ( 26 , 34 , 42 , 43 ), while perpetration prevalence was reported in three studies, ranging from 10.1 to 19.07% ( 34 , 43 , 47 ). An Israeli study suggested that 9.8% of respondents had been excluded from the Internet, while 8.9% had been refused entry to a group or team ( 26 ). A study in South Korea argued that the perpetration prevalence of group violence was 10.1% ( 34 ), while a study in Italy reported that the rate of online group violence against others was 19.07% ( 47 ).

Visual Violence

The prevalence of visual violence victimization was explored within three studies and ranged from 2.6 to 12.1% ( 26 , 34 , 43 ), while the perpetration prevalence reported in four studies ranged from 1.7 to 6% ( 34 , 43 , 47 , 48 ). For victimization prevalence, a South Korean study found that 12.1% of respondents reported that their personal information was leaked online ( 34 ). An Israel study reported that the prevalence of outing the picture was 2.6% ( 26 ). For perpetration prevalence, a South Korean study found that 1.7% of respondents had reported that they had disclosed someone's personal information online ( 34 ). A German study reported that 6% of respondents had written a message (e.g., an email) to somebody using a fake identity ( 48 ).

Impersonating and Account Forgery

Four studies reported on the victimization prevalence of impersonating and account forgery, ranging from 1.1 to 10% ( 15 , 42 , 43 ), while five studies reported on perpetration prevalence, with the range being from 1.3 to 9.31% ( 15 , 43 , 47 , 48 , 51 ). In a Spanish study, 10% of respondents reported that their accounts had been infringed by others or that they could not access their account due to stolen passwords. In contrast, 4.5% of respondents reported that they had infringed other people's accounts or stolen passwords, with 2.5% stating that they had forged other people's accounts ( 51 ). An Israeli study reported that the prevalence of being impersonated was 7% ( 42 ), while in China, a study reported this to be 8.6% ( 43 ). Another study from China found that 1.1% of respondents had been impersonated to send dating-for-money messages ( 15 ).

Other Behaviors

The prevalence of disclosure of privacy, sexual harassment, and cyberstalking were also explored by scholars. Six studies reported the victimization prevalence of other cyberbullying behaviors ( 13 , 15 , 34 , 37 , 42 , 43 ), and four studies reported on perpetration prevalence ( 34 , 37 , 43 , 48 ). A study in China found that 1.2% of respondents reported that their privacy had been compromised without permission due to disputes ( 15 ). A study from China reported the prevalence of cyberstalking victimization was 11.9% ( 43 ), while a Portuguese study reported that this was 62% ( 13 ). In terms of perpetration prevalence, a Malaysian study reported 2.7% for sexual harassment ( 37 ).

Risk and Protective Factors of Cyberbullying

In terms of the risk factors associated with cyberbullying among children and adolescents, this comprehensive review highlighted both personal and situational factors. Personal factors referred to age, gender, online behavior, race, health conditions, past experiences of victimization, and impulsiveness, while situational factors consisted of parent-child relationship, interpersonal relationships, and geographical location. In addition, protective factors against cyberbullying included: empathy and emotional intelligence, parent-child relationship, and school climate. Table 2 shows the risk and protective factors for child and adolescent cyberbullying.

Risk and protective factors of cyberbullying among children and adolescents.

In terms of the risk factors associated with cyberbullying victimization at the personal level, many studies evidenced that females were more likely to be cyberbullied than males ( 13 , 26 , 29 , 38 , 43 , 52 , 54 , 55 , 58 ). Meanwhile, adolescents with mental health problems ( 61 ), such as depression ( 33 , 62 ), borderline personality disorder ( 63 ), eating disorders ( 41 ), sleep deprivation ( 56 ), and suicidal thoughts and suicide plans ( 64 ), were more likely to be associated with cyberbullying victimization. As for Internet usage, researchers agreed that youth victims were probably those that spent more time online than their counterparts ( 32 , 36 , 43 , 45 , 48 , 49 , 60 ). For situational risk factors, some studies have proven the relationship between cyberbullying victims and parental abuse, parental neglect, family dysfunction, inadequate monitoring, and parents' inconsistency in mediation, as well as communication issues ( 33 , 64 , 68 , 73 ). In terms of geographical location, some studies have reported that youths residing in city locations are more likely to be victims of cyberbullying than their peers from suburban areas ( 61 ).

Regarding the risk factors of cyberbullying perpetration at the personal level, it is generally believed that older teenagers, especially those aged over 15 years, are at greater risk of becoming cyberbullying perpetrators ( 55 , 67 ). When considering prior cyberbullying experiences, evidence showed that individuals who had experienced cyberbullying or face-to-face bullying tended to be aggressors in cyberbullying ( 35 , 42 , 49 , 51 , 55 ); in addition, the relationship between impulsiveness and cyberbullying perpetration was also explored by several pioneering scholars ( 55 , 72 , 80 ). The situational factors highlight the role of parents and teachers in cyberbullying experiences. For example, over-control and authoritarian parenting styles, as well as inharmonious teacher-student relationships ( 61 ) are perceived to lead to cyberbullying behaviors ( 74 , 75 ). In terms of differences in geographical locations, students residing in cities have a higher rate of online harassment than students living in more rural locations ( 49 ).

In terms of the protective factors in child and adolescent cyberbullying, scholars have focused on youths who have limited experiences of cyberbullying. At the personal level, high emotional intelligence, an ability for emotional self-control and empathy, such as cognitive empathy ability ( 44 , 55 ), were associated with lower rates of cyberbullying ( 57 ). At the situational level, a parent's role is seen as critical. For example, intimate parent-child relationships ( 46 ) and open active communication ( 19 ) were demonstrated to be related to lower experiences of cyberbullying and perpetration. Some scholars argued that parental supervision and monitoring of children's online activities can reduce their tendency to participate in some negative activities associated with cyberbullying ( 31 , 46 , 73 ). They further claimed that an authoritative parental style protects youths against cyberbullying ( 43 ). Conversely, another string of studies evidenced that parents' supervision of Internet usage was meaningless ( 45 ). In addition to conflicting roles of parental supervision, researchers have also looked into the role of schools, and posited that positive school climates contribute to less cyberbullying experiences ( 61 , 79 ).

Some risk factors may be protective factors under another condition. Some studies suggest that parental aggressive communication is related to severe cyberbullying victims, while open communication is a potential protective factor ( 19 ). Parental neglect, parental abuse, parental inconsistency in supervision of adolescents' online behavior, and family dysfunction are related to the direct or indirect harm of cyberbullying ( 33 , 68 ). Parental participation, a good parental-children relationship, communication and dialogue can enhance children's school adaptability and prevent cyberbullying behaviors ( 31 , 74 ). When parental monitoring reaches a balance between control and openness, it could become a protective factor against cyberbullying, and it could be a risk factor, if parental monitoring is too low or over-controlled ( 47 ).

Despite frequent discussion about the risk factors associated with cyberbullying among children and adolescents, some are still deemed controversial factors, such as age, race, gender, and the frequency of suffering on the internet. For cyberbullying victims, some studies claim that older teenagers are more vulnerable to cyberbullying ( 15 , 38 , 52 , 53 ), while other studies found conflicting results ( 26 , 33 ). As for student race, Alhajji et al. argued that non-white students were less likely to report cyberbullying ( 29 ), while Morin et al. observed no significant correlation between race and cyberbullying ( 52 ). For cyberbullying perpetration, Alvarez-Garcia found that gender differences may have indirect effects on cyberbullying perpetration ( 55 ), while others disagreed ( 42 , 61 , 68 – 70 ). Specifically, some studies revealed that males were more likely to become cyberbullying perpetrators ( 34 , 39 , 56 ), while Khurana et al. presented an opposite point of view, proposing that females were more likely to attack others ( 71 ). In terms of time spent on the Internet, some claimed that students who frequently surf the Internet had a higher chance of becoming perpetrators ( 49 ), while others stated that there was no clear and direct association between Internet usage and cyberbullying perpetration ( 55 ).

In addition to personal and situational factors, scholars have also explored other specific factors pertaining to cyberbullying risk and protection. For instance, mindfulness and depression were found to be significantly related to cyber perpetration ( 76 ), while eating disorder psychopathology in adolescents was associated with cyber victimization ( 41 ). For males who were familiar with their victims, such as family members, friends and acquaintances, they were more likely to be cyberstalking perpetrators than females or strangers, while pursuing desired closer relationships ( 13 ). In the school context, a lower social likability in class was identified as an indirect factor for cyberbullying ( 48 ).

This comprehensive review has established that the prevalence of global childhood and adolescent victimization from cyberbullying ranges from 13.99 to 57.5%, and that the perpetration prevalence ranges from 6.0 to 46.3%. Across the studies included in our research, verbal violence is observed as one of the most common acts of cyberbullying, including verbal offensive responses, insults, mocking, threats, slander, and harassment. The victimization prevalence of verbal violence is reported to be between 5 and 47.5%, and the perpetration prevalence is between 3.2 and 26.1%. Personal factors, such as gender, frequent use of social media platforms, depression, borderline personality disorder, eating disorders, sleep deprivation, and suicidal tendencies, were generally considered to be related to becoming a cyberbullying victim. Personal factors, such as high school students, past experiences, impulse, improperly controlled family education, poor teacher-student relationships, and the urban environment, were considered risk factors for cyberbullying perpetration. Situational factors, including parental abuse and neglect, improper monitoring, communication barriers between parents and children, as well as the urban environment, were also seen to potentially contribute to higher risks of both cyberbullying victimization and perpetration.

Increasing Prevalence of Global Cyberbullying With Changing Social Media Landscape and Measurement Alterations

This comprehensive review suggests that global cyberbullying rates, in terms of victimization and perpetration, were on the rise during the 5 year period, from 2015 to 2019. For example, in an earlier study conducted by Modecki et al. the average cyberbullying involvement rate was 15% ( 81 ). Similar observations were made by Hamm et al. who found that the median rates of youth having experienced bullying or who had bullied others online, was 23 and 15.2%, respectively ( 82 ). However, our systematic review summarized global children and adolescents cyberbullying in the last 5 years and revealed an average cyberbullying perpetration rate of 25.03%, ranging from 6.0 to 46.3%, while the average victimization was 33.08%, ranging from 13.99 to 57.5%. The underlying reason for increases may be attributed to the rapid changing landscape of social media and, in recent years, the drastic increase in Internet penetration rates. With the rise in Internet access, youths have greater opportunities to participate in online activities, provided by emerging social media platforms.

Although our review aims to provide a broader picture of cyberbullying, it is well-noted in extant research that difficulties exist in accurately estimating variations in prevalence in different countries ( 23 , 83 ). Many reasons exist to explain this. The first largely relates poor or unclear definition of the term cyberbullying; this hinders the determination of cyberbullying victimization and perpetration ( 84 ). Although traditional bullying behavior is well-defined, the definition cannot directly be applied to the virtual environment due to the complexity in changing online interactions. Without consensus on definitions, measurement and cyberbullying types may vary noticeably ( 83 , 85 ). Secondly, the estimation of prevalence of cyberbullying is heavily affected by research methods, such as recall period (lifetime, last year, last 6 months, last month, or last week etc.), demographic characteristics of the survey sample (age, gender, race, etc.), perspectives of cyberbullying experiences (victims, perpetrators, or both victim and perpetrator), and instruments (scales, study-specific questions) ( 23 , 84 , 86 ). The variety in research tools and instruments used to assess the prevalence of cyberbullying can cause confusion on this issue ( 84 ). Thirdly, variations in economic development, cultural backgrounds, human values, internet penetration rates, and frequency of using social media may lead to different conclusions across countries ( 87 ).

Acknowledging the Conflicting Role of the Identified Risk Factors With More Research Needed to Establish the Causality

Although this review has identified many personal and situational factors associated with cyberbullying, the majority of studies adopted a cross-sectional design and failed to reveal the causality ( 21 ). Nevertheless, knowledge on these correlational relationships provide valuable insights for understanding and preventing cyberbullying incidents. In terms of gender differences, females are believed to be at a higher risk of cyberbullying victimization compared to males. Two reasons may help to explain this. First, the preferred violence behaviors between two genders. females prefer indirect harassment, such as the spreading of rumors, while males tend toward direct bullying (e.g., assault) ( 29 ) and second, the cultural factors. From the traditional gender perspective, females tended to perceive a greater risk of communicating with others on the Internet, while males were more reluctant to express fear, vulnerability and insecurity when asked about their cyberbullying experiences ( 46 ). Females were more intolerant when experiencing cyberstalking and were more likely to report victimization experiences than males ( 13 ). Meanwhile, many researchers suggested that females are frequent users of emerging digital communication platforms, which increases their risk of unpleasant interpersonal contact and violence. From the perspective of cultural norms and masculinity, the reporting of cyberbullying is also widely acknowledged ( 37 ). For example, in addition, engaging in online activities is also regarded as a critical predictor for cyberbullying victimization. Enabled by the Internet, youths can easily find potential victims and start harassment at any time ( 49 ). Participating in online activities directly increases the chance of experiencing cyberbullying victimization and the possibility of becoming a victim ( 36 , 45 ). As for age, earlier involvement on social media and instant messaging tools may increase the chances of experiencing cyberbullying. For example, in Spain, these tools cannot be used without parental permission before the age of 14 ( 55 ). Besides, senior students were more likely to be more impulsive and less sympathetic. They may portray more aggressive and anti-social behaviors ( 55 , 72 ); hence senior students and students with higher impulsivity were usually more likely to become cyberbullying perpetrators.

Past experiences of victimization and family-related factors are another risk for cyberbullying crime. As for past experiences, one possible explanation is that young people who had experienced online or traditional school bullying may commit cyberbullying using e-mails, instant messages, and text messages for revenge, self-protection, or improving their social status ( 35 , 42 , 49 , 55 ). In becoming a cyberbullying perpetrator, the student may feel more powerful and superior, externalizing angry feelings and relieving the feelings of helplessness and sadness produced by past victimization experiences ( 51 ). As for family related factors, parenting styles are proven to be highly correlated to cyberbullying. In authoritative families, parents focus on rational behavioral control with clear rules and a high component of supervision and parental warmth, which have beneficial effects on children's lifestyles ( 43 ). Conversely, in indulgent families, children's behaviors are not heavily restricted and parents guide and encourage their children to adapt to society. The characteristics of this indulgent style, including parental support, positive communication, low imposition, and emotional expressiveness, possibly contribute to more parent-child trust and less misunderstanding ( 75 ). The protective role of warmth/affection and appropriate supervision, which are common features of authoritative or indulgent parenting styles, mitigate youth engagement in cyberbullying. On the contrary, authoritarian and neglectful styles, whether with excessive or insufficient control, are both proven to be risk factors for being a target of cyberbullying ( 33 , 76 ). In terms of geographical location, although several studies found that children residing in urban areas were more likely to be cyberbullying victims than those living in rural or suburban areas, we cannot draw a quick conclusion here, since whether this difference attributes to macro-level differences, such as community safety or socioeconomic status, or micro-level differences, such as teacher intervention in the classroom, courses provided, teacher-student ratio, is unclear across studies ( 61 ). An alternative explanation for this is the higher internet usage rate in urban areas ( 49 ).

Regarding health conditions, especially mental health, some scholars believe that young people with health problems are more likely to be identified as victims than people without health problems. They perceive health condition as a risk factor for cyberbullying ( 61 , 63 ). On the other hand, another group of scholars believe that cyberbullying has an important impact on the mental health of adolescents which can cause psychological distress consequences, such as post-traumatic stress mental disorder, depression, suicidal ideation, and drug abuse ( 70 , 87 ). It is highly possible that mental health could be risk factors, consequences of cyberbullying or both. Mental health cannot be used as standards, requirements, or decisive responses in cyberbullying research ( 13 ).

The Joint Effort Between Youth, Parents, Schools, and Communities to Form a Cyberbullying-Free Environment

This comprehensive review suggests that protecting children and adolescents from cyberbullying requires joint efforts between individuals, parents, schools, and communities, to form a cyberbullying-free environment. For individuals, young people are expected to improve their digital technology capabilities, especially in the use of social media platforms and instant messaging tools ( 55 ). To reduce the number of cyberbullying perpetrators, it is necessary to cultivate emotional self-regulation ability through appropriate emotional management training. Moreover, teachers, counselors, and parents are required to be armed with sufficient knowledge of emotional management and to develop emotional management capabilities and skills. In this way, they can be alert to the aggressive or angry emotions expressed by young people, and help them mediate any negative emotions ( 45 ), and avoid further anti-social behaviors ( 57 ).

For parents, styles of parenting involving a high level of parental involvement, care and support, are desirable in reducing the possibility of children's engagement in cyberbullying ( 74 , 75 ). If difficulties are encountered, open communication can contribute to enhancing the sense of security ( 73 ). In this vein, parents should be aware of the importance of caring, communicating and supervising their children, and participate actively in their children's lives ( 71 ). In order to keep a balance between control and openness ( 47 ), parents can engage in unbiased open communication with their children, and reach an agreement on the usage of computers and smart phones ( 34 , 35 , 55 ). Similarly, it is of vital importance to establish a positive communication channel with children ( 19 ).

For schools, a higher priority is needed to create a safe and positive campus environment, providing students with learning opportunities and ensuring that every student is treated equally. With a youth-friendly environment, students are able to focus more on their academic performance and develop a strong sense of belonging to the school ( 79 ). For countries recognizing collectivist cultural values, such as China and India, emphasizing peer attachment and a sense of collectivism can reduce the risk of cyberbullying perpetration and victimization ( 78 ). Besides, schools can cooperate with mental health agencies and neighboring communities to develop preventive programs, such as extracurricular activities and training ( 44 , 53 , 62 ). Specifically, school-based preventive measures against cyberbullying are expected to be sensitive to the characteristics of young people at different ages, and the intersection of race and school diversity ( 29 , 76 ). It is recommended that school policies that aim to embrace diversity and embody mutual respect among students are created ( 26 ). Considering the high prevalence of cyberbullying and a series of serious consequences, it is suggested that intervention against cyberbullying starts from an early stage, at about 10 years old ( 54 ). Schools can organize seminars to strengthen communication between teachers and students so that they can better understand the needs of students ( 61 ). In addition, schools should encourage cyberbullying victims to seek help and provide students with opportunities to report cyberbullying behaviors, such as creating online anonymous calls.

Conclusions and Limitations

The comprehensive study has reviewed related research on children and adolescents cyberbullying across different countries and regions, providing a positive understanding of the current situation of cyberbullying. The number of studies on cyberbullying has surged in the last 5 years, especially those related to risk factors and protective factors of cyberbullying. However, research on effective prevention is insufficient and evaluation of policy tools for cyberbullying intervention is a nascent research field. Our comprehensive review concludes with possible strategies for cyberbullying prevention, including personal emotion management, digital ability training, policy applicability, and interpersonal skills. We highlight the important role of parental control in cyberbullying prevention. As for the role of parental control, it depends on whether children believe their parents are capable of adequately supporting them, rather than simply interfering in their lives, restricting their online behavior, and controlling or removing their devices ( 50 ). In general, cyberbullying is on the rise, with the effectiveness of interventions to meet this problem still requiring further development and exploration ( 83 ).

Considering the overlaps between cyberbullying and traditional offline bullying, future research can explore the unique risk and protective factors that are distinguishable from traditional bullying ( 86 ). To further reveal the variations, researchers can compare the outcomes of interventions conducted in cyberbullying and traditional bullying preventions simultaneously, and the same interventions only targeting cyberbullying ( 88 ). In addition, cyberbullying also reflects a series of other social issues, such as personal privacy and security, public opinion monitoring, multinational perpetration and group crimes. To address this problem, efforts from multiple disciplines and novel analytical methods in the digital era are required. As the Internet provides enormous opportunities to connect young people from all over the world, cyberbullying perpetrators may come from transnational networks. Hence, cyberbullying of children and adolescents, involving multiple countries, is worth further attention.

Our study has several limitations. First, national representative studies are scarce, while few studies from middle and low income countries were included in our research due to language restrictions. Many of the studies included were conducted in schools, communities, provinces, and cities in high income countries. Meanwhile, our review only focused on victimization and perpetration. Future studies should consider more perspectives, such as bystanders and those with the dual identity of victim/perpetrator, to comprehensively analyze the risk and protective factors of cyberbullying.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material , further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

SH, CZ, RE, and WZ conceived the study and developed the design. WZ analyzed the result and supervised the study. CZ and SH wrote the first draft. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2021.634909/full#supplementary-material

- 1. Ang RP. Adolescent cyberbullying: a review of characteristics, prevention and intervention strategies. Aggress Violent Behav. (2015) 25:35–42. 10.1016/j.avb.2015.07.011 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Reyna VF, Farley F. Risk and rationality in adolescent decision making: implications for theory, practice, and public policy. Psychol Sci Public Interest. (2006) 7:1–44. 10.1111/j.1529-1006.2006.00026.x [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. UNICEF ed . Children in a Digital World. New York, NY: UNICEF; (2017). [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Thomas HJ, Connor JP, Scott JG. Integrating traditional bullying and cyberbullying: challenges of definition and measurement in adolescents - a review. Educ Psychol Rev. (2015) 27:135–52. 10.1007/s10648-014-9261-7 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Baldry AC, Farrington DP, Sorrentino A. Am I at risk of cyberbullying? A narrative review and conceptual framework for research on risk of cyberbullying and cybervictimization: the risk and needs assessment approach. Aggress Violent Behav. (2015) 23:36–51. 10.1016/j.avb.2015.05.014 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Olweus D. Bullying at School: What We Know and What We Can Do. Oxford; Cambridge, MA: Blackwell; (1993). [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Dooley JJ, Pyzalski J, Cross D. Cyberbullying versus face-to-face bullying: a theoretical and conceptual review. J Psychol. (2009) 217:182–8. 10.1027/0044-3409.217.4.182 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Smith PK, Mahdavi J, Carvalho M, Fisher S, Russell S, Tippett N. Cyberbullying: its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2008) 49:376–85. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01846.x [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Kowalski RM, Giumetti GW, Schroeder AN, Lattanner MR. Bullying in the digital age: a critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychol Bull. (2014) 140:1073–137. 10.1037/a0035618 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. León Vicente I. Cybervictimization by cyberbullying: children at risk and children as risk (dissertation). University of the Basque Country, Leioa, Spain: (2016). [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Identification, Prevention, and Response. (2020). [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Jadambaa A, Thomas HJ, Scott JG, Graves N, Brain D, Pacella R. Prevalence of traditional bullying and cyberbullying among children and adolescents in Australia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2019) 53:878–88. 10.1177/0004867419846393 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Pereira F, Matos M. Cyber-stalking victimization: what predicts fear among Portuguese adolescents? Eur J Crim Policy Res. (2016) 22:253–70. 10.1007/s10610-015-9285-7 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Reed LA, Ward LM, Tolman RM, Lippman JR, Seabrook RC. The association between stereotypical gender and dating beliefs and digital dating abuse perpetration in adolescent dating relationships. J Interpers Violence. (2018). 10.1177/0886260518801933 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Huang CL, Yang SC, Hsieh LS. The cyberbullying behavior of Taiwanese adolescents in an online gaming environment. Children Youth Serv Rev. (2019) 106:104461. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104461 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Raskauskas J, Huynh A. The process of coping with cyberbullying: a systematic review. Aggress Violent Behav. (2015) 23:118–25. 10.1016/j.avb.2015.05.019 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Bradshaw J, Crous G, Rees G, Turner N. Comparing children's experiences of schools-based bullying across countries. Children Youth Serv Rev. (2017) 80:171–80. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.06.060 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Hutson E, Kelly S, Militello LK. Systematic review of cyberbullying interventions for youth and parents with implications for evidence-based practice. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. (2018) 15:72–9. 10.1111/wvn.12257 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Larranaga E, Yubero S, Ovejero A, Navarro R. Loneliness, parent-child communication and cyberbullying victimization among Spanish youths. Comp Hum Behav. (2016) 65:1–8. 10.1016/j.chb.2016.08.015 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. van Geel M, Vedder P, Tanilon J. Relationship between peer victimization, cyberbullying, and suicide in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. (2014) 168:435–42. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4143 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Zych I, Ortega-Ruiz R, Del Rey R. Systematic review of theoretical studies on bullying and cyberbullying: facts, knowledge, prevention, and intervention. Aggress Violent Behav. (2015) 23:1–21. 10.1016/j.avb.2015.10.001 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Selkie EM, Kota R, Chan Y-F, Moreno M. Cyberbullying, depression, and problem alcohol use in female college students: a multisite study. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. (2015) 18:79–86. 10.1089/cyber.2014.0371 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Brochado S, Soares S, Fraga S. A scoping review on studies of cyberbullying prevalence among adolescents. Trauma Violence Abus. (2017) 18:523–31. 10.1177/1524838016641668 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Nocentini A, Calmaestra J, Schultze-Krumbholz A, Scheithauer H, Ortega R, Menesini E. Cyberbullying: labels, behaviours and definition in three European Countries. Aust J Guid Couns. (2010) 20:129–42. 10.1375/ajgc.20.2.129 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Willard NE. Cyberbullying and Cyberthreats: Responding to the Challenge of Online Social Aggression, Threats, and Distress. Champaign: Research Press; (2007). [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Aizenkot D, Kashy-Rosenbaum G. Cyberbullying victimization in whatsapp classmate groups among Israeli Elementary, Middle, and High School Students. J Interpers Violence. (2019). 10.1177/0886260519842860 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Anderson CA, Bushman BJ. Human aggression. Ann Rev Psychol. (2002) 53:27–51. 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135231 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. (2011). Available online at: http://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/ (accessed January 17, 2021).

- 29. Alhajji M, Bass S, Dai T. Cyberbullying, mental health, and violence in adolescents and associations with sex and race: data from the 2015 youth risk behavior survey. Global Pediatr Health. (2019) 6:2333794X19868887. 10.1177/2333794X19868887 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Grinshteyn E, Yang YT. The association between electronic bullying and school absenteeism among high school students in the United States. J School Health. (2017) 87:142–9. 10.1111/josh.12476 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Mesch GS. Parent-child connections on social networking sites and cyberbullying. Youth Soc. (2018) 50:1145–62. 10.1177/0044118X16659685 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Sam J, Wisniewski P, Xu H, Rosson MB, Carroll JM. How are social capital and parental mediation associated with cyberbullying and cybervictimization among youth in the United States? In: Stephanidis C, editor. HCI International 2017 – Posters' Extended Abstracts Communications in Computer Information Science Cham: Springer International Publishing. p. 638–644. [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Hong JS, Kim DH, Thornberg R, Kang JH, Morgan JT. Correlates of direct and indirect forms of cyberbullying victimization involving South Korean adolescents: an ecological perspective. Comput Hum Behav. (2018) 87:327–36. 10.1016/j.chb.2018.06.010 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Lee C, Shin N. Prevalence of cyberbullying and predictors of cyberbullying perpetration among Korean adolescents. Comp Hum Behav. (2017) 68:352–8. 10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.047 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. You S, Lim SA. Longitudinal predictors of cyberbullying perpetration: evidence from Korean middle school students. Person Ind Differ. (2016) 89:172–6. 10.1016/j.paid.2015.10.019 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Holt TJ, Fitzgerald S, Bossler AM, Chee G, Ng E. Assessing the risk factors of cyber and mobile phone bullying victimization in a nationally representative sample of Singapore Youth. Int J Offend Ther Comp Criminol. (2016) 60:598–615. 10.1177/0306624X14554852 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Marret MJ, Choo WY. Factors associated with online victimisation among Malaysian adolescents who use social networking sites: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. (2017) 7:e014959. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014959 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Tesler R, Nissanholtz-Gannot R, Zigdon A, Harel-Fisch Y. The association of cyber-bullying and adolescents in religious and secular schools in Israel. J Relig Health. (2019) 58:2095–109. 10.1007/s10943-019-00938-z [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Beran T, Mishna F, McInroy LB, Shariff S. Children's experiences of cyberbullying: a Canadian National Study. Child School. (2015) 37:207–14. 10.1093/cs/cdv024 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. World Bank Country and Lending Groups – World Bank Data Help Desk . Available online at: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups [accessed January 25, 2021).

- 41. Marco JH, Tormo-Irun P. Cyber victimization is associated with eating disorder psychopathology in adolescents. Front Psychol. (2018) 9:987. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00987 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Olenik-Shemesh D, Heiman T. Cyberbullying victimization in adolescents as related to body esteem, social support, and social self-efficacy. J Genet Psychol. (2017) 178:28–43. 10.1080/00221325.2016.1195331 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. Rao J, Wang H, Pang M, Yang J, Zhang J, Ye Y, et al. Cyberbullying perpetration and victimisation among junior and senior high school students in Guangzhou, China. Inj Prev. (2019) 25:13–9. 10.1136/injuryprev-2016-042210 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. Lee C. Weak Commitment to School, Deviant Peers, and Cyberbullying Victimization-Strain in Adolescent Cyberbullying. (2017). Available online at: https://search.proquest.com/pqdtglobal/docview/1937915933/abstract/9D85437600564444PQ/30 (accessed June 17, 2020).

- 45. Lin MT. Risk factors associated with cyberbullying victimization and perpetration among Taiwan children (dissertation). The University of Texas, Austin, TX, United States: (2019). [ Google Scholar ]

- 46. Pieschl S, Porsch T. The complex relationship between cyberbullying and trust. Int J Dev Sci. (2017) 11:9–17. 10.3233/DEV-160208 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 47. Brighi A, Menin D, Skrzypiec G, Guarini A. Young, bullying, and connected. Common pathways to cyberbullying and problematic internet use in adolescence. Front Psychol. (2019) 10:1467. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01467 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 48. Festl R. Perpetrators on the internet: analyzing individual and structural explanation factors of cyberbullying in school context. Comp Hum Behav. (2016) 59:237–48. 10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.017 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 49. Olumide AO, Adams P, Amodu OK. Prevalence and correlates of the perpetration of cyberbullying among in-school adolescents in Oyo State, Nigeria. Int J Adolesc Med Health. (2016) 28:183–91. 10.1515/ijamh-2015-0009 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 50. Baldry AC, Sorrentino A, Farrington DP. Cyberbullying and cybervictimization versus parental supervision, monitoring and control of adolescents' online activities. Child Youth Serv Rev. (2019) 96:302–7. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.11.058 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 51. Garaigordobil M. Cyberbullying in adolescents and youth in the Basque Country: prevalence of cybervictims, cyberaggressors, and cyberobservers. J Youth Stud. (2015) 18:569–82. 10.1080/13676261.2014.992324 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 52. Morin HK, Bradshaw CP, Kush JM. Adjustment outcomes of victims of cyberbullying: the role of personal and contextual factors. J School Psychol. (2018) 70:74–88. 10.1016/j.jsp.2018.07.002 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 53. Baraldsnes D. The prevalence of cyberbullying and the views of 5-12 grade pupils and teachers on cyberbullying prevention in Lithuanian Schools. Uinv J Educ Res. (2015) 3:949–59. 10.13189/ujer.2015.031201 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 54. Razjouyan K, Mobarake AH, Sadr SS, Ardestani SMS, Yaseri M. The relationship between emotional intelligence and the different roles in cyberbullying among high school students in Tehran. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. (2018) 12:UNSP e11560. 10.5812/ijpbs.11560 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 55. Alvarez-Garcia D, Carlos Nunez J, Garcia T, Barreiro-Collazo A. Individual, family, and community predictors of cyber-aggression among adolescents. Eur J Psychol Appl Legal Context. (2018) 10:79–88. 10.5093/ejpalc2018a8 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 56. Horzum MB, Ayas T, Randler C, Dusunceli B. The effects of empathy and circadian preference on cyberbullying of adolescents in Turkey. Biol Rhythm Res. (2019). 10.1080/09291016.2019.1603839 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 57. Carmen Martinez-Monteagudo M, Delgado B, Manuel Garcia-Fernandez J, Rubio E. Cyberbullying, aggressiveness, and emotional intelligence in adolescence. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:5079. 10.3390/ijerph16245079 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 58. Sasson H, Mesch G. The role of parental mediation and peer norms on the likelihood of cyberbullying. J Genet Psychol. (2017) 178:15–27. 10.1080/00221325.2016.1195330 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 59. Wang X, Lei L, Liu D, Hu H. Moderating effects of moral reasoning and gender on the relation between moral disengagement and cyberbullying in adolescents. Person Ind Differ. (2016) 98:244–9. 10.1016/j.paid.2016.04.056 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 60. Simsek N, Sahin D, Evli M. Internet addiction, cyberbullying, and victimization relationship in adolescents a sample from Turkey. J Addict Nurs. (2019) 30:201–10. 10.1097/JAN.0000000000000296 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 61. McQuillan BE. Ecological Factors Associated with Middle School Students' Experiences of Cyberbullying. (2016). Available online at: https://search.proquest.com/pqdtglobal/docview/1794167537/abstract/9D85437600564444PQ/4 (accessed June 17, 2020).

- 62. Rose CA, Tynes BM. Longitudinal associations between cybervictimization and mental health among U.S. adolescents. J Adolesc Health. (2015) 57:305–12. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.05.002 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 63. Stockdale LA, Coyne SM, Nelson DA, Erickson DH. Borderline personality disorder features, jealousy, and cyberbullying in adolescence. Pers Individ Differ. (2015) 83:148–53. 10.1016/j.paid.2015.04.003 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 64. Chen Q, Lo Camilla KM, Yuhong Z, Anne C, Ling CK, Patrick I. Family poly-victimization and cyberbullying among adolescents in a Chinese school sample. Child Abuse Negl. (2018) 77:180–7. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.01.015 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 65. Landoll RR, La Greca AM, Lai BS, Chan SF, Herge WM. Cyber victimization by peers: prospective associations with adolescent social anxiety and depressive symptoms. J Adolesc. (2015) 42:77–86. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.04.002 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 66. Iranzo B, Buelga S, Cava M-J, Ortega-Baron J. Cyberbullying, psychosocial adjustment, and suicidal ideation in adolescence. Psychosoc Interv. (2019) 28:75–81. 10.5093/pi2019a5 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 67. Buelga S, Cava MJ, Musitu G, Torralba E. Cyberbullying aggressors among Spanish secondary education students: an exploratory study. Interact Tech Smart Ed. (2015) 12:100–15. 10.1108/ITSE-08-2014-0025 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 68. Katz I, Lemish D, Cohen R, Arden A. When parents are inconsistent: parenting style and adolescents' involvement in cyberbullying. J Adolesc. (2019) 74:1–2. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.04.006 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 69. Cénat JM, Blais M, Lavoie F, Caron P-O, Hébert M. Cyberbullying victimization and substance use among Quebec high schools students: the mediating role of psychological distress. Comp Hum Behav. (2018) 89:207–12. 10.1016/j.chb.2018.08.014 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 70. Hoareau N, Bages C, Allaire M, Guerrien A. The role of psychopathic traits and moral disengagement in cyberbullying among adolescents. Crim Behav Ment Health. (2019) 29:321–31. 10.1002/cbm.2135 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 71. Khurana A, Bleakley A, Jordan A, Romer D. The protective effects of parental monitoring and internet restriction on adolescents' risk of online harassment. J Youth Adolesc. (2015) 44:1039–47. 10.1007/s10964-014-0242-4 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 72. Martínez I, Murgui S, Garcia OF, Garcia F. Parenting in the digital era: protective and risk parenting styles for traditional bullying and cyberbullying victimization. Comp Hum Behav. (2019) 90:84–92. 10.1016/j.chb.2018.08.036 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 73. Yusuf S, Salleh H, Bahaman A, Shamsul M, Ramli N, Ramli AN, et al. Parental attachment and cyberbullying experiences among Malaysian children. Pertanika J Scholarly Res Rev. (2018) 4:67–80. [ Google Scholar ]

- 74. Martinez-Ferrer B, Leon-Moreno C, Musitu-Ferrer D, Romero-Abrio A, Callejas-Jeronimo JE, Musitu-Ochoa G. Parental socialization, school adjustment and cyber-aggression among adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:4005. 10.3390/ijerph16204005 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 75. Moreno–Ruiz D, Martínez–Ferrer B, García–Bacete F. Parenting styles, cyberaggression, and cybervictimization among adolescents. Comp Hum Behav. (2019) 93:252–9. 10.1016/j.chb.2018.12.031 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 76. Ho SS, Chen L, Ng APY. Comparing cyberbullying perpetration on social media between primary and secondary school students. Comp Educ. (2017) 109:74–84. 10.1016/j.compedu.2017.02.004 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 77. Gómez-Ortiz O, Romera EM, Ortega-Ruiz R, Del Rey R. Parenting practices as risk or preventive factors for adolescent involvement in cyberbullying: contribution of children and parent gender. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2018) 15:2664. 10.3390/ijerph15122664 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 78. Wright MF, Kamble SV, Soudi SP. Indian adolescents' cyber aggression involvement and cultural values: the moderation of peer attachment. Sch Psychol Int. (2015) 36:410–27. 10.1177/0143034315584696 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 79. Holfeld B, Leadbeater BJ. Concurrent and longitudinal associations between early adolescents' experiences of school climate and cyber victimization. Comput Hum Behav. (2017) 76:321–8. 10.1016/j.chb.2017.07.037 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 80. Álvarez-García D, Núñez JC, González-Castro P, Rodríguez C, Cerezo R. The effect of parental control on cyber-victimization in adolescence: the mediating role of impulsivity and high-risk behaviors. Front Psychol. (2019) 10:1159. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01159 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 81. Modecki KL, Minchin J, Harbaugh AG, Guerra NG, Runions KC. Bullying prevalence across contexts: a meta-analysis measuring cyber and traditional bullying. J Adolesc Health. (2014) 55:602–11. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.06.007 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 82. Hamm MP, Newton AS, Chisholm A, Shulhan J, Milne A, Sundar P, et al. Prevalence and effect of cyberbullying on children and young people: a scoping review of social media studies. JAMA Pediatr. (2015) 169:770. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0944 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 83. Gaffney H, Farrington DP, Espelage DL, Ttofi MM. Are cyberbullying intervention and prevention programs effective? A systematic and meta-analytical review. Aggress Violent Behav. (2019) 45:134–53. 10.1016/j.avb.2018.07.002 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 84. Selkie EM, Fales JL, Moreno MA. Cyberbullying prevalence among US middle and high school-aged adolescents: a systematic review and quality assessment. J Adolesc Health. (2016) 58:125–33. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.09.026 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 85. Ybarra ML, Boyd D, Korchmaros JD, Oppenheim J. Defining and measuring cyberbullying within the larger context of bullying victimization. J Adolesc Health. (2012) 51:53–8. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.031 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 86. Kowalski RM, Limber SP, McCord A. A developmental approach to cyberbullying: prevalence and protective factors. Aggress Violent Behav. (2019) 45:20–32. 10.1016/j.avb.2018.02.009 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 87. Dilmac B, Yurt E, Aydin M, Kasarci I. Predictive relationship between humane values of adolescents cyberbullying and cyberbullying sensibility. Electron J Res Educ Psychol. (2016) 14:3–22. 10.14204/ejrep.38.14123 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 88. Reed KP, Cooper RL, Nugent WR, Russell K. Cyberbullying: a literature review of its relationship to adolescent depression and current intervention strategies. J Hum Behav Soc Environ. (2016) 26:37–45. 10.1080/10911359.2015.1059165 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

- View on publisher site

- PDF (890.5 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Cyberbullying: A Systematic Literature Review to Identify the Factors Impelling University Students Towards Cyberbullying

Ieee account.

- Change Username/Password

- Update Address

Purchase Details

- Payment Options

- Order History

- View Purchased Documents

Profile Information

- Communications Preferences

- Profession and Education

- Technical Interests

- US & Canada: +1 800 678 4333

- Worldwide: +1 732 981 0060

- Contact & Support

- About IEEE Xplore

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Nondiscrimination Policy

- Privacy & Opting Out of Cookies

A not-for-profit organization, IEEE is the world's largest technical professional organization dedicated to advancing technology for the benefit of humanity. © Copyright 2024 IEEE - All rights reserved. Use of this web site signifies your agreement to the terms and conditions.

Cyberbullying in adolescents: a literature review

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Health Education and Behavioral Sciences, Faculty of Public Health, Mahidol University, Bangkok 10400, Thailand.

- PMID: 35245420

- DOI: 10.1515/ijamh-2021-0133

Cyberbullying is a universal public health concern that affects adolescents. The growing usage of electronic gadgets and the Internet has been connected to a rise in cyberbullying. The increasing use of the Internet, along with the negative outcomes of cyberbullying on adolescents, has required the study of cyberbullying. In this paper author reviews existing literature on cyberbullying among adolescents. The concept of cyberbullying is explained, including definitions, types of cyberbullying, characteristics or features of victims and cyberbullies, risk factors or causes underlying cyberbullying, and the harmful consequences of cyberbullying to adolescents. Furthermore, examples of programs or intervention to prevent cyberbullying and recommendations for further studies are presented.

Keywords: adolescents; cyberbullying; literature review.

© 2022 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston.

Publication types

- Adolescent Behavior*

- Bullying* / prevention & control

- Crime Victims*

- Cyberbullying*

- Risk Factors

Official websites use .gov

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Frequent Social Media Use and Experiences with Bullying Victimization, Persistent Feelings of Sadness or Hopelessness, and Suicide Risk Among High School Students — Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2023

Supplements / October 10, 2024 / 73(4);23–30

Please note: This report has been corrected.

Emily Young, MSEd, MPH 1 ; Jessica L. McCain, PhD 2 ; Melissa C. Mercado, PhD 2 ; Michael F. Ballesteros, PhD 3 ; Shamia Moore, MPH 3 ; Laima Licitis, MPH 1 ,4 ; Joi Stinson, MPH 1 ,4 ; Sherry Everett Jones, PhD 1 ; Natalie J. Wilkins, PhD 1 ( View author affiliations )

Introduction

Limitations, future directions, acknowledgments.

- Article PDF

- Full Issue PDF

Social media has become a pervasive presence in everyday life, including among youths. In 2023, for the first time, CDC’s nationally representative Youth Risk Behavior Survey included an item assessing U.S. high school students’ frequency of social media use. Data from this survey were used to estimate the prevalence of frequent social media use (i.e., used social media at least several times a day) among high school students and associations between frequent social media use and experiences with bullying victimization, persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness, and suicide risk. All prevalence estimates and measures of association used Taylor series linearization. Prevalence ratios were calculated using logistic regression with predicted marginals. Overall, 77.0% of students reported frequent social media use, with observed differences by sex, sexual identity, and racial and ethnic identity. Frequent social media use was associated with a higher prevalence of bullying victimization at school and electronically, persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness, and some suicide risk among students (considering attempting suicide and having made a suicide plan), both overall and in stratified models. This analysis characterizes the potential harms of frequent social media use for adolescent health among a nationally representative sample of U.S. high school students. Findings might support multisectoral efforts to create safer digital environments for youths, including decision-making about social media policies, practices, and protections.

Social media, defined as “Internet-based channels that allow users to opportunistically interact and selectively self-present, either in real-time or asynchronously, with both broad and narrow audiences who derive value from user-generated content and the perception of interaction with others , ” has become a pervasive presence in everyday life, including among youths ( 1 ). Recent data indicate that approximately 95% of high school–aged youths use a social media platform, with approximately one fifth reporting “almost constant” social media use ( 2 ). Associations between frequent social media use and poor mental health outcomes among adolescents, including depression ( 3 ) and suicide risk ( 4 ), are being increasingly documented. Social media use might also increase risk for electronic victimization and perpetration ( 5 ), which can be antecedents of poor mental health. Evidence suggests that certain youth populations might be more vulnerable than others to potential harms of social media use, such as female and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning adolescents, who are more likely to experience electronic victimization than male or heterosexual peers ( 5 – 7 ). However, youths might also benefit from social support and connection found online ( 4 , 8 ). Understanding potential risks and benefits of social media use is critical for preparing youths to safely engage in an increasingly digitalized world.

This report uses 2023 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) data to build on extant literature by examining associations between frequent social media use and U.S. high school students’ experiences of bullying victimization, persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness, and suicide risk. Understanding such patterns and relations might guide public health practitioners’ efforts to prevent violence and injury and promote mental health, in line with Healthy People 2030 objectives ( https://health.gov/healthypeople ). Findings from this report might also support multilevel decision-making about social media use and cross-sectoral initiatives (e.g., education, technology, and policy) to create safer digital environments for youths.

Data Source

This report includes data from the 2023 YRBS (N = 20,103), a cross-sectional, school-based survey conducted biennially since 1991. Each survey year, CDC collects data from a nationally representative sample of public and private school students in grades 9–12 in the 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia. Additional information about YRBS sampling, data collection, response rates, and processing is available in the overview report of this supplement ( 9 ). The prevalence estimates for frequent social media use for the study population overall and stratified by sex, race and ethnicity, grade, and sexual identity are available at https://nccd.cdc.gov/youthonline/App/Default.aspx . The full YRBS questionnaire, data sets, and documentation are available at https://www.cdc.gov/yrbs/index.html . Institutional reviews boards at CDC and ICF, the survey contractor, approved the protocol for YRBS. Data collection was conducted consistent with applicable Federal law and CDC policy.*