STUDENT ESSAY The Disproportional Impact of COVID-19 on African Americans

Volume 22/2, December 2020, pp 299-307

Maritza Vasquez Reyes

Introduction

We all have been affected by the current COVID-19 pandemic. However, the impact of the pandemic and its consequences are felt differently depending on our status as individuals and as members of society. While some try to adapt to working online, homeschooling their children and ordering food via Instacart, others have no choice but to be exposed to the virus while keeping society functioning. Our different social identities and the social groups we belong to determine our inclusion within society and, by extension, our vulnerability to epidemics.

COVID-19 is killing people on a large scale. As of October 10, 2020, more than 7.7 million people across every state in the United States and its four territories had tested positive for COVID-19. According to the New York Times database, at least 213,876 people with the virus have died in the United States. [1] However, these alarming numbers give us only half of the picture; a closer look at data by different social identities (such as class, gender, age, race, and medical history) shows that minorities have been disproportionally affected by the pandemic. These minorities in the United States are not having their right to health fulfilled.

According to the World Health Organization’s report Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health , “poor and unequal living conditions are the consequences of deeper structural conditions that together fashion the way societies are organized—poor social policies and programs, unfair economic arrangements, and bad politics.” [2] This toxic combination of factors as they play out during this time of crisis, and as early news on the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic pointed out, is disproportionately affecting African American communities in the United States. I recognize that the pandemic has had and is having devastating effects on other minorities as well, but space does not permit this essay to explore the impact on other minority groups.

Employing a human rights lens in this analysis helps us translate needs and social problems into rights, focusing our attention on the broader sociopolitical structural context as the cause of the social problems. Human rights highlight the inherent dignity and worth of all people, who are the primary rights-holders. [3] Governments (and other social actors, such as corporations) are the duty-bearers, and as such have the obligation to respect, protect, and fulfill human rights. [4] Human rights cannot be separated from the societal contexts in which they are recognized, claimed, enforced, and fulfilled. Specifically, social rights, which include the right to health, can become important tools for advancing people’s citizenship and enhancing their ability to participate as active members of society. [5] Such an understanding of social rights calls our attention to the concept of equality, which requires that we place a greater emphasis on “solidarity” and the “collective.” [6] Furthermore, in order to generate equality, solidarity, and social integration, the fulfillment of social rights is not optional. [7] In order to fulfill social integration, social policies need to reflect a commitment to respect and protect the most vulnerable individuals and to create the conditions for the fulfillment of economic and social rights for all.

Disproportional impact of COVID-19 on African Americans

As noted by Samuel Dickman et al.:

economic inequality in the US has been increasing for decades and is now among the highest in developed countries … As economic inequality in the US has deepened, so too has inequality in health. Both overall and government health spending are higher in the US than in other countries, yet inadequate insurance coverage, high-cost sharing by patients, and geographical barriers restrict access to care for many. [8]

For instance, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation, in 2018, 11.7% of African Americans in the United States had no health insurance, compared to 7.5% of whites. [9]

Prior to the Affordable Care Act—enacted into law in 2010—about 20% of African Americans were uninsured. This act helped lower the uninsured rate among nonelderly African Americans by more than one-third between 2013 and 2016, from 18.9% to 11.7%. However, even after the law’s passage, African Americans have higher uninsured rates than whites (7.5%) and Asian Americans (6.3%). [10] The uninsured are far more likely than the insured to forgo needed medical visits, tests, treatments, and medications because of cost.

As the COVID-19 virus made its way throughout the United States, testing kits were distributed equally among labs across the 50 states, without consideration of population density or actual needs for testing in those states. An opportunity to stop the spread of the virus during its early stages was missed, with serious consequences for many Americans. Although there is a dearth of race-disaggregated data on the number of people tested, the data that are available highlight African Americans’ overall lack of access to testing. For example, in Kansas, as of June 27, according to the COVID Racial Data Tracker, out of 94,780 tests, only 4,854 were from black Americans and 50,070 were from whites. However, blacks make up almost a third of the state’s COVID-19 deaths (59 of 208). And while in Illinois the total numbers of confirmed cases among blacks and whites were almost even, the test numbers show a different picture: 220,968 whites were tested, compared to only 78,650 blacks. [11]

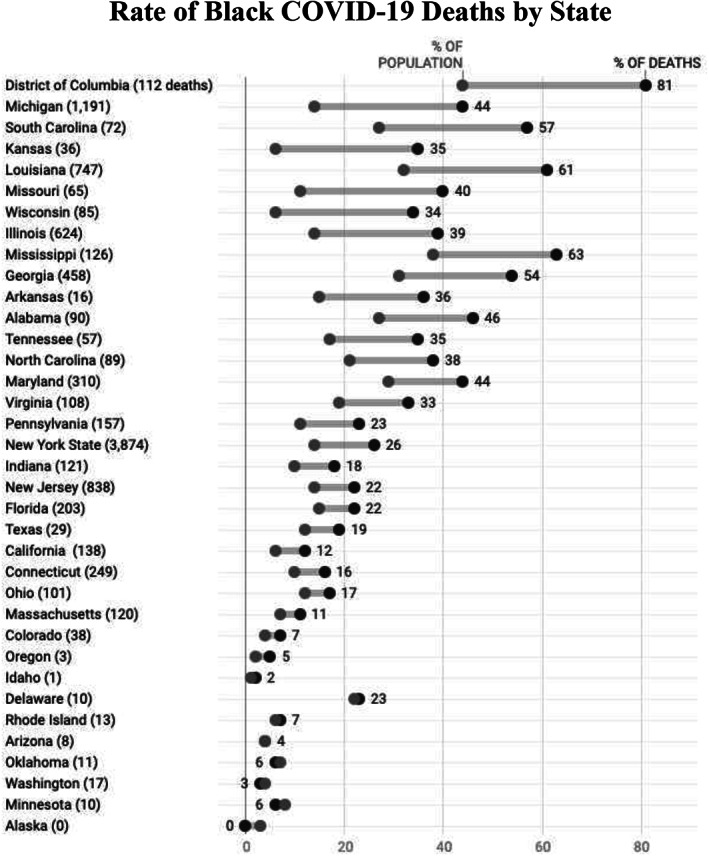

Similarly, American Public Media reported on the COVID-19 mortality rate by race/ethnicity through July 21, 2020, including Washington, DC, and 45 states (see figure 1). These data, while showing an alarming death rate for all races, demonstrate how minorities are hit harder and how, among minority groups, the African American population in many states bears the brunt of the pandemic’s health impact.

Approximately 97.9 out of every 100,000 African Americans have died from COVID-19, a mortality rate that is a third higher than that for Latinos (64.7 per 100,000), and more than double than that for whites (46.6 per 100,000) and Asians (40.4 per 100,000). The overrepresentation of African Americans among confirmed COVID-19 cases and number of deaths underscores the fact that the coronavirus pandemic, far from being an equalizer, is amplifying or even worsening existing social inequalities tied to race, class, and access to the health care system.

Considering how African Americans and other minorities are overrepresented among those getting infected and dying from COVID-19, experts recommend that more testing be done in minority communities and that more medical services be provided. [12] Although the law requires insurers to cover testing for patients who go to their doctor’s office or who visit urgent care or emergency rooms, patients are fearful of ending up with a bill if their visit does not result in a COVID test. Furthermore, minority patients who lack insurance or are underinsured are less likely to be tested for COVID-19, even when experiencing alarming symptoms. These inequitable outcomes suggest the importance of increasing the number of testing centers and contact tracing in communities where African Americans and other minorities reside; providing testing beyond symptomatic individuals; ensuring that high-risk communities receive more health care workers; strengthening social provision programs to address the immediate needs of this population (such as food security, housing, and access to medicines); and providing financial protection for currently uninsured workers.

Social determinants of health and the pandemic’s impact on African Americans’ health outcomes

In international human rights law, the right to health is a claim to a set of social arrangements—norms, institutions, laws, and enabling environment—that can best secure the enjoyment of this right. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights sets out the core provision relating to the right to health under international law (article 12). [13] The United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights is the body responsible for interpreting the covenant. [14] In 2000, the committee adopted a general comment on the right to health recognizing that the right to health is closely related to and dependent on the realization of other human rights. [15] In addition, this general comment interprets the right to health as an inclusive right extending not only to timely and appropriate health care but also to the determinants of health. [16] I will reflect on four determinants of health—racism and discrimination, poverty, residential segregation, and underlying medical conditions—that have a significant impact on the health outcomes of African Americans.

Racism and discrimination

In spite of growing interest in understanding the association between the social determinants of health and health outcomes, for a long time many academics, policy makers, elected officials, and others were reluctant to identify racism as one of the root causes of racial health inequities. [17] To date, many of the studies conducted to investigate the effect of racism on health have focused mainly on interpersonal racial and ethnic discrimination, with comparatively less emphasis on investigating the health outcomes of structural racism. [18] The latter involves interconnected institutions whose linkages are historically rooted and culturally reinforced. [19] In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, acts of discrimination are taking place in a variety of contexts (for example, social, political, and historical). In some ways, the pandemic has exposed existing racism and discrimination.

Poverty (low-wage jobs, insurance coverage, homelessness, and jails and prisons)

Data drawn from the 2018 Current Population Survey to assess the characteristics of low-income families by race and ethnicity shows that of the 7.5 million low-income families with children in the United States, 20.8% were black or African American (while their percentage of the population in 2018 was only 13.4%). [20] Low-income racial and ethnic minorities tend to live in densely populated areas and multigenerational households. These living conditions make it difficult for low-income families to take necessary precautions for their safety and the safety of their loved ones on a regular basis. [21] This fact becomes even more crucial during a pandemic.

Low-wage jobs: The types of work where people in some racial and ethnic groups are overrepresented can also contribute to their risk of getting sick with COVID-19. Nearly 40% of African American workers, more than seven million, are low-wage workers and have jobs that deny them even a single paid sick day. Workers without paid sick leave might be more likely to continue to work even when they are sick. [22] This can increase workers’ exposure to other workers who may be infected with the COVID-19 virus.

Similarly, the Centers for Disease Control has noted that many African Americans who hold low-wage but essential jobs (such as food service, public transit, and health care) are required to continue to interact with the public, despite outbreaks in their communities, which exposes them to higher risks of COVID-19 infection. According to the Centers for Disease Control, nearly a quarter of employed Hispanic and black or African American workers are employed in service industry jobs, compared to 16% of non-Hispanic whites. Blacks or African Americans make up 12% of all employed workers but account for 30% of licensed practical and licensed vocational nurses, who face significant exposure to the coronavirus. [23]

In 2018, 45% of low-wage workers relied on an employer for health insurance. This situation forces low-wage workers to continue to go to work even when they are not feeling well. Some employers allow their workers to be absent only when they test positive for COVID-19. Given the way the virus spreads, by the time a person knows they are infected, they have likely already infected many others in close contact with them both at home and at work. [24]

Homelessness : Staying home is not an option for the homeless. African Americans, despite making up just 13% of the US population, account for about 40% of the nation’s homeless population, according to the Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress. [25] Given that people experiencing homelessness often live in close quarters, have compromised immune systems, and are aging, they are exceptionally vulnerable to communicable diseases—including the coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

Jails and prisons : Nearly 2.2 million people are in US jails and prisons, the highest rate in the world. According to the US Bureau of Justice, in 2018, the imprisonment rate among black men was 5.8 times that of white men, while the imprisonment rate among black women was 1.8 times the rate among white women. [26] This overrepresentation of African Americans in US jails and prisons is another indicator of the social and economic inequality affecting this population.

According to the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights’ General Comment 14, “states are under the obligation to respect the right to health by, inter alia , refraining from denying or limiting equal access for all persons—including prisoners or detainees, minorities, asylum seekers and illegal immigrants—to preventive, curative, and palliative health services.” [27] Moreover, “states have an obligation to ensure medical care for prisoners at least equivalent to that available to the general population.” [28] However, there has been a very limited response to preventing transmission of the virus within detention facilities, which cannot achieve the physical distancing needed to effectively prevent the spread of COVID-19. [29]

Residential segregation

Segregation affects people’s access to healthy foods and green space. It can also increase excess exposure to pollution and environmental hazards, which in turn increases the risk for diabetes and heart and kidney diseases. [30] African Americans living in impoverished, segregated neighborhoods may live farther away from grocery stores, hospitals, and other medical facilities. [31] These and other social and economic inequalities, more so than any genetic or biological predisposition, have also led to higher rates of African Americans contracting the coronavirus. To this effect, sociologist Robert Sampson states that the coronavirus is exposing class and race-based vulnerabilities. He refers to this factor as “toxic inequality,” especially the clustering of COVID-19 cases by community, and reminds us that African Americans, even if they are at the same level of income or poverty as white Americans or Latino Americans, are much more likely to live in neighborhoods that have concentrated poverty, polluted environments, lead exposure, higher rates of incarceration, and higher rates of violence. [32]

Many of these factors lead to long-term health consequences. The pandemic is concentrating in urban areas with high population density, which are, for the most part, neighborhoods where marginalized and minority individuals live. In times of COVID-19, these concentrations place a high burden on the residents and on already stressed hospitals in these regions. Strategies most recommended to control the spread of COVID-19—social distancing and frequent hand washing—are not always practical for those who are incarcerated or for the millions who live in highly dense communities with precarious or insecure housing, poor sanitation, and limited access to clean water.

Underlying health conditions

African Americans have historically been disproportionately diagnosed with chronic diseases such as asthma, hypertension and diabetes—underlying conditions that may make COVID-19 more lethal. Perhaps there has never been a pandemic that has brought these disparities so vividly into focus.

Doctor Anthony Fauci, an immunologist who has been the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases since 1984, has noted that “it is not that [African Americans] are getting infected more often. It’s that when they do get infected, their underlying medical conditions … wind them up in the ICU and ultimately give them a higher death rate.” [33]

One of the highest risk factors for COVID-19-related death among African Americans is hypertension. A recent study by Khansa Ahmad et al. analyzed the correlation between poverty and cardiovascular diseases, an indicator of why so many black lives are lost in the current health crisis. The authors note that the American health care system has not yet been able to address the higher propensity of lower socioeconomic classes to suffer from cardiovascular disease. [34] Besides having higher prevalence of chronic conditions compared to whites, African Americans experience higher death rates. These trends existed prior to COVID-19, but this pandemic has made them more visible and worrisome.

Addressing the impact of COVID-19 on African Americans: A human rights-based approach

The racially disparate death rate and socioeconomic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the discriminatory enforcement of pandemic-related restrictions stand in stark contrast to the United States’ commitment to eliminate all forms of racial discrimination. In 1965, the United States signed the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, which it ratified in 1994. Article 2 of the convention contains fundamental obligations of state parties, which are further elaborated in articles 5, 6, and 7. [35] Article 2 of the convention stipulates that “each State Party shall take effective measures to review governmental, national and local policies, and to amend, rescind or nullify any laws and regulations which have the effect of creating or perpetuating racial discrimination wherever it exists” and that “each State Party shall prohibit and bring to an end, by all appropriate means, including legislation as required by circumstances, racial discrimination by any persons, group or organization.” [36]

Perhaps this crisis will not only greatly affect the health of our most vulnerable community members but also focus public attention on their rights and safety—or lack thereof. Disparate COVID-19 mortality rates among the African American population reflect longstanding inequalities rooted in systemic and pervasive problems in the United States (for example, racism and the inadequacy of the country’s health care system). As noted by Audrey Chapman, “the purpose of a human right is to frame public policies and private behaviors so as to protect and promote the human dignity and welfare of all members and groups within society, particularly those who are vulnerable and poor, and to effectively implement them.” [37] A deeper awareness of inequity and the role of social determinants demonstrates the importance of using right to health paradigms in response to the pandemic.

The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has proposed some guidelines regarding states’ obligation to fulfill economic and social rights: availability, accessibility, acceptability, and quality. These four interrelated elements are essential to the right to health. They serve as a framework to evaluate states’ performance in relation to their obligation to fulfill these rights. In the context of this pandemic, it is worthwhile to raise the following questions: What can governments and nonstate actors do to avoid further marginalizing or stigmatizing this and other vulnerable populations? How can health justice and human rights-based approaches ground an effective response to the pandemic now and build a better world afterward? What can be done to ensure that responses to COVID-19 are respectful of the rights of African Americans? These questions demand targeted responses not just in treatment but also in prevention. The following are just some initial reflections:

First, we need to keep in mind that treating people with respect and human dignity is a fundamental obligation, and the first step in a health crisis. This includes the recognition of the inherent dignity of people, the right to self-determination, and equality for all individuals. A commitment to cure and prevent COVID-19 infections must be accompanied by a renewed commitment to restore justice and equity.

Second, we need to strike a balance between mitigation strategies and the protection of civil liberties, without destroying the economy and material supports of society, especially as they relate to minorities and vulnerable populations. As stated in the Siracusa Principles, “[state restrictions] are only justified when they support a legitimate aim and are: provided for by law, strictly necessary, proportionate, of limited duration, and subject to review against abusive applications.” [38] Therefore, decisions about individual and collective isolation and quarantine must follow standards of fair and equal treatment and avoid stigma and discrimination against individuals or groups. Vulnerable populations require direct consideration with regard to the development of policies that can also protect and secure their inalienable rights.

Third, long-term solutions require properly identifying and addressing the underlying obstacles to the fulfillment of the right to health, particularly as they affect the most vulnerable. For example, we need to design policies aimed at providing universal health coverage, paid family leave, and sick leave. We need to reduce food insecurity, provide housing, and ensure that our actions protect the climate. Moreover, we need to strengthen mental health and substance abuse services, since this pandemic is affecting people’s mental health and exacerbating ongoing issues with mental health and chemical dependency. As noted earlier, violations of the human rights principles of equality and nondiscrimination were already present in US society prior to the pandemic. However, the pandemic has caused “an unprecedented combination of adversities which presents a serious threat to the mental health of entire populations, and especially to groups in vulnerable situations.” [39] As Dainius Pūras has noted, “the best way to promote good mental health is to invest in protective environments in all settings.” [40] These actions should take place as we engage in thoughtful conversations that allow us to assess the situation, to plan and implement necessary interventions, and to evaluate their effectiveness.

Finally, it is important that we collect meaningful, systematic, and disaggregated data by race, age, gender, and class. Such data are useful not only for promoting public trust but for understanding the full impact of this pandemic and how different systems of inequality intersect, affecting the lived experiences of minority groups and beyond. It is also important that such data be made widely available, so as to enhance public awareness of the problem and inform interventions and public policies.

In 1966, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said, “Of all forms of inequality, injustice in health is the most shocking and inhuman.” [41] More than 54 years later, African Americans still suffer from injustices that are at the basis of income and health disparities. We know from previous experiences that epidemics place increased demands on scarce resources and enormous stress on social and economic systems.

A deeper understanding of the social determinants of health in the context of the current crisis, and of the role that these factors play in mediating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on African Americans’ health outcomes, increases our awareness of the indivisibility of all human rights and the collective dimension of the right to health. We need a more explicit equity agenda that encompasses both formal and substantive equality. [42] Besides nondiscrimination and equality, participation and accountability are equally crucial.

Unfortunately, as suggested by the limited available data, African American communities and other minorities in the United States are bearing the brunt of the current pandemic. The COVID-19 crisis has served to unmask higher vulnerabilities and exposure among people of color. A thorough reflection on how to close this gap needs to start immediately. Given that the COVID-19 pandemic is more than just a health crisis—it is disrupting and affecting every aspect of life (including family life, education, finances, and agricultural production)—it requires a multisectoral approach. We need to build stronger partnerships among the health care sector and other social and economic sectors. Working collaboratively to address the many interconnected issues that have emerged or become visible during this pandemic—particularly as they affect marginalized and vulnerable populations—offers a more effective strategy.

Moreover, as Delan Devakumar et al. have noted:

the strength of a healthcare system is inseparable from broader social systems that surround it. Health protection relies not only on a well-functioning health system with universal coverage, which the US could highly benefit from, but also on social inclusion, justice, and solidarity. In the absence of these factors, inequalities are magnified and scapegoating persists, with discrimination remaining long after. [43]

This current public health crisis demonstrates that we are all interconnected and that our well-being is contingent on that of others. A renewed and healthy society is possible only if governments and public authorities commit to reducing vulnerability and the impact of ill-health by taking steps to respect, protect, and fulfill the right to health. [44] It requires that government and nongovernment actors establish policies and programs that promote the right to health in practice. [45] It calls for a shared commitment to justice and equality for all.

Maritza Vasquez Reyes, MA, LCSW, CCM, is a PhD student and Research and Teaching Assistant at the UConn School of Social Work, University of Connecticut, Hartford, USA.

Please address correspondence to the author. Email: [email protected].

Competing interests: None declared.

Copyright © 2020 Vasquez Reyes. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

[1] “Coronavirus in the U.S.: Latest map and case count,” New York Times (October 10, 2020). Available at https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/coronavirus-us-cases.html.

[2] World Health Organization Commission on the Social Determinants of Health, Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health (Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008), p. 1.

[3] S. Hertel and L. Minkler, Economic rights: Conceptual, measurement, and policy issues (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007); S. Hertel and K. Libal, Human rights in the United States: Beyond exceptionalism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011); D. Forsythe, Human rights in international relations , 2nd edition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

[4] Danish Institute for Human Rights, National action plans on business and human rights (Copenhagen: Danish Institute for Human Rights, 2014).

[5] J. R. Blau and A. Moncada, Human rights: Beyond the liberal vision (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2005).

[6] J. R. Blau. “Human rights: What the United States might learn from the rest of the world and, yes, from American sociology,” Sociological Forum 31/4 (2016), pp. 1126–1139; K. G. Young and A. Sen, The future of economic and social rights (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2019).

[7] Young and Sen (see note 6).

[8] S. Dickman, D. Himmelstein, and S. Woolhandler, “Inequality and the health-care system in the USA,” Lancet , 389/10077 (2017), p. 1431.

[9] S. Artega, K. Orgera, and A. Damico, “Changes in health insurance coverage and health status by race and ethnicity, 2010–2018 since the ACA,” KFF (March 5, 2020). Available at https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/changes-in-health-coverage-by-race-and-ethnicity-since-the-aca-2010-2018/.

[10] H. Sohn, “Racial and ethnic disparities in health insurance coverage: Dynamics of gaining and losing coverage over the life-course,” Population Research and Policy Review 36/2 (2017), pp. 181–201.

[11] Atlantic Monthly Group, COVID tracking project . Available at https://covidtracking.com .

[12] “Why the African American community is being hit hard by COVID-19,” Healthline (April 13, 2020). Available at https://www.healthline.com/health-news/covid-19-affecting-people-of-color#What-can-be-done?.

[13] World Health Organization, 25 questions and answers on health and human rights (Albany: World Health Organization, 2002).

[14] Ibid; Hertel and Libal (see note 3).

[17] Z. Bailey, N. Krieger, M. Agénor et al., “Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions,” Lancet 389/10077 (2017), pp. 1453–1463.

[20] US Census. Available at https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2019/demo/p60-266.html.

[21] M. Simms, K. Fortuny, and E. Henderson, Racial and ethnic disparities among low-income families (Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute Publications, 2009).

[23] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Health Equity Considerations and Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups (2020). Available at https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/health-equity/race-ethnicity.html.

[24] Artega et al. (see note 9).

[25] K. Allen, “More than 50% of homeless families are black, government report finds,” ABC News (January 22, 2020). Available at https://abcnews.go.com/US/50-homeless-families-black-government-report-finds/story?id=68433643.

[26] A. Carson, Prisoners in 2018 (US Department of Justice, 2020). Available at https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p18.pdf.

[27] United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No. 14, The Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health, UN Doc. E/C.12/2000/4 (2000).

[28] J. J. Amon, “COVID-19 and detention,” Health and Human Rights 22/1 (2020), pp. 367–370.

[30] L. Pirtle and N. Whitney, “Racial capitalism: A fundamental cause of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic inequities in the United States,” Health Education and Behavior 47/4 (2020), pp. 504–508.

[31] Ibid; R. Sampson, “The neighborhood context of well-being,” Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 46/3 (2003), pp. S53–S64.

[32] C. Walsh, “Covid-19 targets communities of color,” Harvard Gazette (April 14, 2020). Available at https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2020/04/health-care-disparities-in-the-age-of-coronavirus/.

[33] B. Lovelace Jr., “White House officials worry the coronavirus is hitting African Americans worse than others,” CNBC News (April 7, 2020). Available at https://www.cnbc.com/2020/04/07/white-house-officials-worry-the-coronavirus-is-hitting-african-americans-worse-than-others.html.

[34] K. Ahmad, E. W. Chen, U. Nazir, et al., “Regional variation in the association of poverty and heart failure mortality in the 3135 counties of the United States,” Journal of the American Heart Association 8/18 (2019).

[35] D. Desierto, “We can’t breathe: UN OHCHR experts issue joint statement and call for reparations” (EJIL Talk), Blog of the European Journal of International Law (June 5, 2020). Available at https://www.ejiltalk.org/we-cant-breathe-un-ohchr-experts-issue-joint-statement-and-call-for-reparations/.

[36] International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, G. A. Res. 2106 (XX) (1965), art. 2.

[37] A. Chapman, Global health, human rights and the challenge of neoliberal policies (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), p. 17.

[38] N. Sun, “Applying Siracusa: A call for a general comment on public health emergencies,” Health and Human Rights Journal (April 23, 2020).

[39] D. Pūras, “COVID-19 and mental health: Challenges ahead demand changes,” Health and Human Rights Journal (May 14, 2020).

[41] M. Luther King Jr, “Presentation at the Second National Convention of the Medical Committee for Human Rights,” Chicago, March 25, 1966.

[42] Chapman (see note 35).

[43] D. Devakumar, G. Shannon, S. Bhopal, and I. Abubakar, “Racism and discrimination in COVID-19 responses,” Lancet 395/10231 (2020), p. 1194.

[44] World Health Organization (see note 12).

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Social Vulnerability and Equity: The Disproportionate Impact of COVID‐19

Tia sherèe gaynor, meghan e wilson.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Revised 2020 Jun 6; Received 2020 May 1; Accepted 2020 Jun 17; Issue date 2020 Sep-Oct.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

As the architect of racial disparity, racism shapes the vulnerability of communities. Socially vulnerable communities are less resilient in their ability to respond to and recover from natural and human‐made disasters compared with resourced communities. This essay argues that racism exposes practices and structures in public administration that, along with the effects of COVID‐19, have led to disproportionate infection and death rates of Black people. Using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Social Vulnerability Index, the authors analyze the ways Black bodies occupy the most vulnerable communities, making them bear the brunt of COVID‐19's impact. The findings suggest that existing disparities exacerbate COVID‐19 outcomes for Black people. Targeted universalism is offered as an administrative framework to meet the needs of all people impacted by COVID‐19.

COVID‐19 emerged of unknown origin in the last quarter of 2019, first gaining global attention from an outbreak of respiratory illness in Wuhan, China (Hui et al. 2020 ; Roberts 2020 ). The virus had reached pandemic levels by March 2020, with countries around the world implementing various forms of public health measures designed to reduce the rate of infection (Adhanom Ghebreyesus 2020 ). As of this writing, the virus had killed 382,867 people globally and 110,562 people in the United States, infected 6.4 million, and touched everyone (Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center 2020 ). While much about COVID‐19 remains a mystery, symptomatically, the virus manifests as troubled breathing, a cough, persistent muscle pain or pressure in the chest, and confusion (CDC 2020 ). The symptoms of COVID‐19 are, in many ways, like the symptoms of American racism—pressure and pain that stifles one's ability to breathe and move freely. Outcomes associated with the daily conditions of Black life in the most vulnerable communities predispose Black people to a host of disparities, health and otherwise (Budoff et al. 2006 ; Gupta, Carrión‐Carire, and Weiss 2006 ; Hoberman 2012 ; Mehta et al. 2006 ; Wright and Merritt 2020 ). COVID‐19, for some, further exposes and reiterates, for others, half a millennium of structural racism and repression targeted with administrative precision on the Black body.

As the architect of racial disparity, racism also shapes the vulnerability of communities. Socially vulnerable communities were created through political decisions such as redlining, gentrification, and industrialization and are less resilient in their ability to respond to and recover from natural and human‐made disasters compared with higher‐resourced communities (Pulido 2000 ). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines social vulnerability as “the resilience of communities when confronted by external stresses on human health, stresses such as natural or human‐caused disasters, or disease outbreaks” (CDC 2018 ). Socially vulnerable communities (and those living within them) may not be able to respond to COVID‐19 in ways that limit the spread and deathly impact of the virus.

In this essay, we argue that racism exposes structures, policies, and practices that have created social vulnerability. Consequently, these vulnerabilities have interacted with the effects of COVID‐19 in such a way that has led to disproportionate infection and death rates of Black people in the United States. To make this argument, we use the CDC's Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) to analyze the ways in which Black bodies occupy the most vulnerable communities, making them bear the brunt of COVID‐19's impact. Because of high‐level vulnerabilities in many Black communities, the pathogen of racism carries COVID‐19 in such a way that it permeates every aspect of Black life. By using the SVI, we are able to locate the vulnerabilities in a county and examine the relationship between social vulnerability and the Black infection and death rates due to COVID‐19. Ultimately, we seek to understand whether there is a relationship between social vulnerability and the disparate impact of COVID‐19 on Black bodies.

We observe the SVI of two locales—Cuyahoga County, Ohio, and Wayne County, Michigan—along with the death rates of Black people due to COVID‐19 in these counties. We propose the use of targeted universalism as a practice‐oriented framework that achieves universal goals through targeted strategies. Inherently, policy and administrative practices take either a universal approach—guaranteeing a uniform set of rights or benefits for all people, regardless of their social group membership (e.g., the right to vote)—or a targeted approach—policy provisions for specific social groups, generally while excluding others (e.g., the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program or SNAP). This approach allows the policy discourse to shape implementation and, ultimately, operates to maintain and/or exacerbate inequities (Starke 2020 ). Conversely, targeted universalism aids policy makers and administrators in responding to COVID‐19 and its disparate effects by developing an outcome‐oriented policy strategy that sets and achieves universal goals through transactional and transformative changes that benefit the most marginalized, thus benefiting the collective (powell, Menendian, and Ake 2019 ).

Living as the Vulnerable

For some communities across the country, natural disasters, human‐made events, and disease outbreaks have the potential to impose drastic hardships on local infrastructure and individuals living within these communities. Factors such as poverty, poor housing conditions, and inadequate transportation can exacerbate the local impact of emergency events, making some communities more vulnerable to human suffering than others (CDC 2018 ). Social vulnerability, therefore, refers to the demographic and socioeconomic factors that shape a community's resilience, particularly as it relates to preparing for, responding to, and managing emergency events—natural and otherwise (CDC 2018 ; Flanagan et al. 2011 ). Even within communities, the impact of disaster events is inequitable and fall largely along racial and economic lines (Flanagan et al. 2011 ).

On March 31, 2020, when referring to the coronavirus, New York governor Andrew Cuomo tweeted “this virus is the great equalizer.” 1 Madonna, in an Instagram post that was later deleted, stated, “what's terrible about it is that it's made us all equal in many ways—and what's wonderful about it is that it's made us all equal in many ways.” 2 While perhaps well intentioned, Governor Cuomo's tweet and Madonna's post advance a wider narrative that suggests that everyone, despite their social group membership, has the same potential to be impacted by the virus and in similar ways. However, the “great equalizer” narrative, which has gained some traction in media outlets, runs counter to the historical patterns evident in disasters throughout U.S. history. Emergency management researchers have demonstrated that the impact of emergency events is not random but is, rather, informed “by everyday patterns of social interaction and organization, particularly the resulting stratification paradigms which determine access to resources” (Morrow 1999 , 2). Existing inequitable social structures and conditions facilitate vastly different realities for more vulnerable communities and individuals when coping with and being resilient to disaster events. As population characteristics directly impact social vulnerability in contexts of natural and human‐made disasters, it would seem to also hold true with the COVID‐19 pandemic. Perhaps rather than the “great equalizer,” COVID‐19 is “the great revealer” of the persistent inequity that has caused long‐standing social vulnerability (Dahir 2020 ).

Preliminary data indicate that people of color, primarily Black people, are overwhelmingly and disproportionately affected by the spread of the COVID‐19 virus. In fact, the CDC reported that as of May 15, 2020, 40 percent of national COVID‐19 hospitalizations were non‐Hispanic Black people, compared with 36.5 percent non‐Hispanic White, 14.2 percent Hispanic, and 9.3 percent other (CDC 2020 ). When comparing these hospitalization rates with population estimates, Black people are, according to these data, hospitalized at a rate almost 3.1 times their population size and the only racial group drastically above their population estimates. Where Black people make up 13.4 percent of the U.S. population, they represent 40 percent of COVID‐19 related hospitalizations (CDC 2020 ; U.S. Census Bureau n.d. ). This disproportionate impact is also evident at the state level. In Illinois, Black people represent 14 percent of the state's population yet 41 percent of those who have died from COVID‐19 (reported as of May 3, 2020) (Illinois Department of Public Health 2020 ). Black people make up 14 percent of Michigan's population but 40 percent of COVID‐19‐related death cases (APM Research Lab 2020 ; DeShay 2020 ; Michigan.gov 2020 ). As figure 1 highlights, this trend can be seen across the majority of states reporting race‐based COVID‐19 data.

Rate of Black COVID‐19 Deaths by State.

Note: Total deaths given in parentheses.

Sources: APM Research Lab, data as of April 27, 2020; CDC Social Vulnerability Index.

A community's ability to respond to and recover from a disastrous event rests on social and economic resources. Being able to carry out the recommended practices to “flatten the curve” and slow the spread of COVID‐19 requires individuals and communities access to the privileges that afford such a response. Charles Blow ( 2020 ) illustrated in an April 2020 New York Times opinion piece that the privilege of social distancing is not an option for many in the Black community. Black people make up large percentages of the essential workforce and frontline jobs, including workers in grocery and courier delivery, postal service, public and urban transport, and health care (DeShay 2020 ). Therefore, those who are working are less able to engage in social distancing practices, as for many, social distancing would mean no income (Pedersen and Favero 2020 ). Further, the Pew Research Center ( 2020 ) revealed that Black survey respondents are twice as likely to know someone who has been hospitalized or died from COVID‐19. These disparities underscore the presence of institutional racism in existing public systems (e.g., housing, industrialization, health care, public education, employment patterns, among many others) and the failure of systemic public administration to address the race‐based inequities that left communities vulnerable to heightened COVID‐19 impacts.

Investigating Social Vulnerability and Black Deaths

To explore the relationship between social vulnerability and the disparate impact of COVID‐19, we focus our investigation on Cuyahoga County, Ohio, and Wayne County, Michigan, as each county has the largest Black population in its state. Specifically, we explore the proposition that Black people are more likely to live in communities that are deemed socially vulnerable and, therefore, more likely to be infected by or die from COVID‐19. Our proposition is rooted in a history of social science research that considers that marginally situated people—specifically Black—are left in the most vulnerable communities without necessary resources to mobilize or shift circumstances. These communities have been stripped of its resources and are often in areas where residents are more likely to be exposed to environmental hazards (Mays, Cochran, and Barnes 2007 ; Wilson 2010). At the intersection of being in highly vulnerable communities, being exposed to environmental injustices, and racism is a perfect storm with Black communities at the center of the COVID‐19 pandemic (Gupta 2020 ; Taylor 2020 ). Therefore, we consider the role that racism has played in the creation of socially vulnerable communities and its implications for strengthening equitable public management and emergency relief approaches in local responses to COVID‐19.

Nationally, the response to COVID‐19 has been a patchwork of public officials updating their knowledge base and leveraging resources where possible. In Ohio and Michigan, the governors reacted quickly with stay‐at‐home orders issued to take effect on March 22 and 23, respectively. This universal approach was intended to slow the transmission of the virus; however, it did not consider that businesses deemed essential are occupied by a largely Black labor force. Policy makers, alternatively, could have created an approach that acknowledged that laborers deemed essential were more vulnerable to infection and proceeded accordingly.

In 2007, shortly after the signing of the Pandemic and All‐Hazards Preparedness Act of 2006, the CDC created the Social Vulnerability Index based on U.S. census data from 2000; it is updated with both census and American Community Survey data. The SVI is a database and mapping tool designed to aid public health and disaster management officials in identifying communities with higher vulnerabilities before, during, and after a disaster or emergency crisis (Flanagan et al. 2011 ). Data used to determine the SVI are based on 15 variables across four individual and community measures: (1) socioeconomic status; (2) household composition and disability; (3) race, ethnicity, and language; and (4) housing and transportation. The SVI produces a score, on a scale from 0 to 1 (lowest to highest vulnerabilities), for each U.S. county and census tract.

Considering the nascency of COVID‐19, data consist of an amalgamation of several sources selected because they are up to date and verifiable. We compared the SVIs of Cuyahoga and Wayne Counties with their respective COVID‐19 confirmed cases and deaths. We recognize there is limited demographic data on COVID‐19, as the CDC, the federal government broadly, and states are not all sharing race‐specific data. Our findings are preliminary and simply show a relationship that requires further investigation when more robust data are made available.

For COVID‐19 data, we use the State of Ohio's COVID‐19 dashboard, the State of Michigan's coronavirus data source, the CDC's Data and Surveillance site, the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center, the AWS COVID‐19 Data Lake for hospitalization, and GitHub. We focus on data that use both laboratory‐confirmed cases and presumed cases, as well as a true case fatality rate (CFR). For consistency, we emphasize data that explore testing capacity because the information is integral to producing the most holistic evidence, even as we accept that all data at this time are incomplete.

Other than the clear limitations for epidemiological and public health reasons, we know that no local, county, state, or federal government entity has produced a uniform collection of race data in COVID‐19 reporting (Wolfe 2020 ). The methods for racial transparency have been ad hoc since the government was called out in early April for its failure to report racial demographics on people impacted by COVID‐19. The government's formal reply was a report that suggested that “black populations might be disproportionately affected by COVID‐19” (Garg 2020 ). This analysis does not suggest causality but rather trends and trajectories in the available data.

The two counties were selected because they have similar compositions and racial, financial, and industrial histories. Both of these counties have embarked on a re‐creation since the Great Recession, which hit the midwestern region hard, stifling their resilience. Cuyahoga County is in the northeastern part of Ohio and home to Cleveland. The SVI score for Cuyahoga County is 0.6552, indicating moderate to high levels of vulnerabilities. Wayne County is a densely populated area in southeastern Michigan that is known for its ties to the auto industry through Detroit. While it is home to multinational conglomerates, it is also one of Michigan's most vulnerable communities, with a SVI score of 0.8682, marking it as a highly vulnerable community.

Beginning with vulnerability allows us to observe the baseline susceptibility of a community to any disaster; we are then able to adapt that susceptibility to COVID‐19. The SVI considers that vulnerable populations are more disadvantaged in disasters; therefore, it gives more insight into just how vulnerable these populations are when considering the ways COVID‐19 spreads. Densely populated communities are impacted because people have less room to socially distance. SVI indicators are most informative as we consider the transmission of COVID‐19. Seven of these indicators—(1) population over 65, (2) single‐parent households with children under 18, (3) household structures with more than 10 units, (4) more people than rooms, (5) no vehicle available, (6) percent population below poverty, and (7) percent minority population—directly interact with vulnerable populations (e.g., age) to create difficulty in social distancing and shelter‐in‐place orders. Table 1 shows the SVI indicators for the two counties. On the surface, these communities are pretty similar for scales of presumed social vulnerability. Thus, perhaps, both communities are almost equally vulnerable to the virus.

Social Vulnerability Indicators in Cuyahoga County, OH, and Wayne County, MI (percent)

Source: CDC Social Vulnerability Index.

These data do not show that either community is more exponentially vulnerable to the virus than the other, but both have vulnerabilities. Wayne County has a higher population of underrepresented people by 10 percent. However, that 10 percent shift does not account for the differential in infections and deaths due to COVID‐19 that separates these communities (see table 2 ). Wayne County has eight times the number of total infections and 16 times the number of deaths as Cuyahoga County. Both of these communities are vulnerable, but only one, Wayne County, has 2,213 deaths because of COVID‐19, of which 1,255 are in Detroit.

COVID‐19 Data

Sources: CDC Case Dashboard; Michigan COVID‐19 Dashboard; Ohio COVID‐19 Dashboard; COVID‐19 Data Lake.

In addition to social vulnerability, we examined the hospitalization rate and hospital capacity in these communities. Hospitalization rate was considered because the CDC indicated that hospital capacity would be the factor that hamstrung the health care system (Devakumar et al. 2020 ; Garg 2020 ). Data show that across the United States, Black people are hospitalized at higher rates, in part because of higher rates of COVID‐19 comorbidities (e.g., asthma, heart disease, obesity, etc.). With these other health conditions, if they contract the virus, Black people are more likely to need respiratory therapy (Zephyrin et al. 2020 ). Both hospital systems are running below capacity and prepared to expand if needed. Cuyahoga is at 55.2 percent intensive care unit (ICU) bed utilization and Wayne is at 67.2 percent ICU bed utilization. The hospitals have not yet reached their capacity, yet more people are dying in Wayne County than in Cuyahoga County. The CFR is higher in Wayne than in Cuyahoga even with widespread testing efforts. Wayne County has a CFR of 10.9 percent, and the Black population has an estimated 12 percent CFR. Table 2 shows rates of infection and percentages of people infected and killed by race. Strikingly, the entire state of Ohio has fewer deaths than Wayne County.

The CFR and rate of infection are vastly underreported because of the lack of free and available testing, which would show asymptomatic cases and shift the denominator on the CFR. Access to testing would have allowed officials to isolate quickly and stop community spread. With these limited data, we are confident in noting preliminary trends that warrant further research, but show promising results that support the proposition. Black people do live in communities that are deemed socially vulnerable; therefore, more likely to contract or die from COVID‐19.

Targeted Universalism for Systemic Change

To restate, the focus of this essay is to examine the relationship between social vulnerability, as measured by the SVI, and the Black infection and death rate due to COVID‐19. Our theoretical mechanisms are rooted in the United States' history of racial bias and social vulnerability.

Ruth Wilson Gilmore ( 2007 , 28) defines racism as “the state‐sanctioned or extralegal production and exploitation of group‐differentiated vulnerability to premature death.” As our findings reveal, socially vulnerable communities, oftentimes communities that are predominantly Black, lack the infrastructure to adequately respond to the impact of COVID‐19 and thus are experiencing disproportionately higher rates of infection and deaths. The relationship between social vulnerability and COVID‐19 outcomes underlines how imperative an equitable public administration is to the well‐being of society at large. Elected officials and career administrators have maintained inequitable systems that operate in such a way that a community's ability to manage a disaster is largely based on its members' access to resources, including economic and racial capital. Communities where redlining occurred, where schools are segregated, and where jobs are scarce are more socially vulnerable. Communities that are economically disadvantaged and have higher concentrations of individuals being discriminated against because of their racial and/or ethnic identity are also more likely to have a higher vulnerability rating.

The legacy of racism and capitalism that has been disproportionately entrenched in Black communities leaves Black people more vulnerable to premature death in the face of COVID‐19. Similar outcomes were present when the levees broke after Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans (Flanagan et al. 2011 ; Stivers 2007 ), in Houston after Hurricane Harvey (Bodenreider et al. 2019 ), and in so many other communities, with many disasters. The difference now seems only to be that this time the disaster is not weather related, but a viral outbreak. Following Gilmore's definition, the social vulnerability allowed to persist in communities across the United States has led to group‐differentiated effects, that in the context of COVID‐19, has prematurely killed Black people at a much higher rate than people of all other ethnic and racial groups.

What can be gleaned, as early lessons, from a better understanding of the trends highlighted? What seems clear is that the maintenance of status quo administration allows for racially disparate outcomes. As long as administrators operate with a business‐as‐usual approach, these racialized disparities will continue. Powell ( 2020 ) argues that targeted universalism can be used as a strategy to address the complexities and nuanced nature of the COVID‐19 pandemic, particularly how it impacts different people in different ways. Targeted universalism is a framework to develop inclusive policies and programs that consider the needs of all groups in order to move everyone toward a universal goal. This approach differs from others as it is designed with a focus on inclusion and undermines “active or passive forces of structural exclusion and marginalization, and promotes tangible experiences of belonging. Outgroups are moved from societal neglect to the center of societal care at the same time that more powerful or favored groups' needs are addressed” (powell, Menendian, and Ake 2019 , 6). Such an approach requires a range of strategies to facilitate long‐term, transformative impacts.

As states begin to relax stay‐at‐home orders, the possibility of increases in overall infection and death rates looms. This means that Black communities are likely to bear the brunt of the compounded impacts of COVID's initial effects and any subsequent spikes. Targeted universalism allows for a coordinated response that addresses the current and potential future impacts of COVID‐19 for those in resource rich and vulnerable communities. Using a five‐step process, decision makers can work to create and implement their COVID‐19 responses to be targeted, with universal impact (powell, Menendian, and Ake 2019 ).

The process begins with the identification of a universal goal stemming from a shared societal problem. Currently, local governments across the country are working to slow the spread of COVID‐19 and reduce the number of new cases and related deaths. Second, assessing the overall population performance as it relates to this goal sets a baseline metric for COVID infection and death rates. Having this baseline allows administrators to closely examine the gaps in infection and death rates specific to vulnerable groups. This baseline, while not an overall measure to evaluate the success of an implemented strategy, offers insight into the severity of the problem being addressed.

Having this information makes it easier for administrators to, third, identify populations whose measures are below the baseline metric. Collecting and examining race‐based data—in a uniform, institutionalized, and systemic manner—allows for the identification of existing COVID‐19 inequities as they relate to individuals living in socially vulnerable communities. Data highlighting racial inequity helps administrators, fourth, understand how existing structures advance or limit vulnerable populations from achieving the universal goal. Having a clear understanding of the communities that are more socially vulnerable and the policies and practices that have, over time, allowed these communities to remain and/or grow in this vulnerability enables decisions to be made in such a way that considers and perhaps addresses the structural and systemic barriers that have exacerbated COVID's impact on Black people.

Lastly, the development and implementation of targeted strategies that aid the collective in meeting the universal goal is required. This may include, but is certainly not limited to: extending stay‐at‐home orders allowing frontline workers to remain at home with pay, decreasing their chances of viral exposure; strengthening the quality of health care systems in socially vulnerable communities; and developing equitable and accessible transportation systems that ease one's ability to access quality health care providers.

Preliminary data reveal that Black life is extremely susceptible to the impacts of the COVID‐19 pandemic (Deslatte, Hatch, and Stokan 2020 ). Racism, for Black people, under the conditions of COVID‐19 operates as a comorbidity (Austin 2020 ). In a just society, race would not shape one's likelihood of dying from a viral pandemic. Underscoring the data is something far greater than differences in infection and death rates. Underlying these data are systems of oppression. What we know about COVID‐19 is that, as a virus, it does not see race, gender, or class, yet it interacts with each of these modifiers in ways that exacerbate the existing oppressive systems that operate to maintain social hierarchy. At a time when New York City is digging mass graves and Michigan communities are scouting ice rinks to store the deceased (Anderson 2020 ; Dixon 2020 ; Entress, Tyler, and Sadiq 2020 ), it feels like a new age, a new day, a new moment. Perhaps the most difficult question is, is the targeting of Black bodies, outside of labor, new in the United States? The novel coronavirus has all but halted the vast majority of the global labor market, but as this essay reveals it is also halting the Black body.

Biographies

Tia Sherèe Gaynor (she/her) is assistant professor in political science and director of the Center for Truth, Racial Healing, and Transformation at the University of Cincinnati. Her research focuses on the unjust experiences that individuals at the intersection of race, gender identity, and sexual orientation have when interacting with systemic racism and social hierarchy in public administration.

Email: [email protected]

Meghan E. Wilson (she/her) is research associate in political science at Michigan State University. Her research centers public finance, political institutions, and marginally situated people—with a focus on the urban core.

Email: [email protected]

Andrew Cuomo (@NYGovCuomo), “This virus is the great equalizer. Stay strong little brother. You are a sweet, beautiful guy and my best friend. If anyone is #NewYorkTough it's you,” Twitter, March 31, 2020, 12:13 p.m., https://twitter.com/NYGovCuomo/status/1245021319646904320 .

Madonna (@madonna), “That's the thing about COVID‐19, It doesn't care about how rich you are, how famous you are, how funny you are, how smart you are, where you live, how old you are, what amazing stories you can tell. It's the great equalizer and what's terrible about it is what's great about it. What's terrible about it is that it's made us all equal in many ways, and what's wonderful about it is that it's made us all equal in many ways. Like I used to say at the end of ‘Human Nature’ every night, if the ship goes down, we're all going down together,” Instagram, March 22, 2020.

- Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Tedros . 2020. WHO Director‐General's Opening Remarks at the Mission Briefing on COVID‐19. February 19. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who‐director‐general‐s‐opening‐remarks‐at‐the‐mission‐briefing‐on‐covid‐19 [accessed March 12, 2020].

- Anderson, Meg . 2020. Burials on New York Island Are Not New, but Are Increasing during Pandemic. National Public Radio, April 10. https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus‐live‐updates/2020/04/10/831875297/burials‐on‐new‐york‐island‐are‐not‐new‐but‐are‐increasing‐during‐pandemic [accessed April 10, 2020].

- APM Research Lab . 2020. The Color of Coronavirus: COVID‐19 Deaths by Race and Ethnicity in the U.S. https://www.apmresearchlab.org/covid/deaths‐by‐race [accessed April 28, 2020].

- Austin, John C . 2020. “COVID‐19 Is Turning the Midwest's Long Legacy of Segregation Deadly.” Brookings. April 30, 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the‐avenue/2020/04/17/covid‐19‐is‐turning‐the‐midwests‐long‐legacy‐of‐segregation‐deadly/ .

- Blow, Charles M. 2020. Social Distancing Is a Privilege. New York Times , April 5. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/05/opinion/coronavirus‐social‐distancing.html [accessed July 28, 2020].

- Bodenreider, Coline , Wright Lindsey, Barr Omid, Xu Kevin, and Wilson Sacoby. 2019. Assessment of Social, Economic, and Geographic Vulnerability Pre‐ and Post‐Hurricane Harvey in Houston, Texas. Environmental Justice 12(4): 182–93. 10.1089/env.2019.0001. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Budoff, Matthew J. , Nasir Khurram, Mao Songshou, Tseng Philip H., Chau Alex, Liu Sandy T., Flores Ferdinand, and Blumenthal Roger S.. 2006. Ethnic Differences of the Presence and Severity of Coronary Atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 187(2): 343–50. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.09.013. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . 2018. CDC's Social Vulnerability Index. https://svi.cdc.gov/index.html [accessed September 5, 2018].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . 2020. Symptoms of Coronavirus. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019‐ncov/symptoms‐testing/symptoms.html [accessed April 27, 2020].

- Dahir, Abdi . 2020. Instead of Coronavirus, the Hunger Will Kill Us. A Global Food Crisis Looms. New York Times , April 22, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/22/world/africa/coronavirus‐hunger‐crisis.html [accessed July 28, 2020 ].

- DeShay, Akiim . 2020. Black COVID‐19 Tracker. https://blackdemographics.com/black‐covid‐19‐tracker/ [accessed May 1, 2020].

- Deslatte, Aaron , Hatch Meghan E., and Stokan Eric. 2020. How Can Local Governments Address Pandemic Inequities? Public Administration Review 80(5): 827–31. 10.1111/puar.13257. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Devakumar, Delan , Shannon Geordan, Bhopal Sunil S., and Abubakar Ibrahim. 2020. Racism and Discrimination in COVID‐19 Responses. The Lancet 395(10231): 1194. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30792-3. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dixon, Jennifer . 2020. Oakland County Scouts Ice Rinks to Potentially Store Bodies in “Last Resort” Scenario. Detroit Free Press , April 15. https://www.freep.com/story/news/local/2020/04/15/coronavirus‐oakland‐ice‐rinks‐bodies/5137771002/ [accessed July 28, 2020].

- Entress, Rebecca , Tyler Jenna, and Sadiq Abdul‐Akeem. 2020. Managing Mass Fatalities during COVID‐19: Lessons for Promoting Community Resilience during Global Pandemics. Public Administration Review 80(5): 856–61. 10.1111/puar.13232. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Flanagan, Barry E. , Gregory Edward W., Hallisey Elaine J., Heitgerd Janet L., and Lewis Brian. 2011. A Social Vulnerability Index for Disaster Management. Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management 8(1): 1–24. 10.2202/1547-7355.1792. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Garg, Shikha . 2020. Hospitalization Rates and Characteristics of Patients Hospitalized with Laboratory‐Confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019—COVID‐NET, 14 States, March 1–30, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 69(15): 458–64. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e3. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gilmore, Ruth Wilson . 2007. Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California. Berkeley: University of California Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gupta, Ruchi S. , Carrión‐Carire Violeta, and Weiss Kevin B.. 2006. The Widening Black/White Gap in Asthma Hospitalizations and Mortality. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 117(2): 351–8. 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.11.047. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gupta, Sujata . 2020. Why African‐Americans May be Especially Vulnerable to COVID‐19. Science News (blog), April 10. https://www.sciencenews.org/article/coronavirus‐why‐african‐americans‐vulnerable‐covid‐19‐health‐race [accessed July 28, 2020].

- Hoberman, John M. 2012. Black and Blue: The Origins and Consequences of Medical Racism. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Hui, David S. , Azhar Esam I., Madani Tariq A., Ntoumi Francine, Kock Richard, Dar Osman, Ippolito Giuseppe, et al. 2020. The Continuing 2019‐NCoV Epidemic Threat of Novel Coronaviruses to Global Health—The Latest 2019 Novel Coronavirus Outbreak in Wuhan, China. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 91: 264–6. 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.009. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Illinois Department of Public Health . 2020. COVID‐19 Statistics. https://www.dph.illinois.gov/covid19/covid19‐statistics [accessed May 18, 2020].

- Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center . 2020. COVID‐19 United States Cases by County. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/us‐map [accessed May 17, 2020].

- Mays, Vickie M. , Cochran Susan D., and Barnes Namdi W.. 2007. Race, Race‐Based Discrimination, and Health Outcomes among African Americans. Annual Review of Psychology 58: 201–25. 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190212. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mehta, Rajendra H. , Marks David, Califf Robert M., Sohn SeeHyang, Pieper Karen S., Van De Werf Frans, Peterson Eric D., et al. 2006. Differences in the Clinical Features and Outcomes in African Americans and Whites with Myocardial Infarction. American Journal of Medicine 119(1): 70.e1–8. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.07.043. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Michigan.gov. 2020. Coronavirus: Michigan Data. https://www.michigan.gov/coronavirus/0,9753,7‐406‐98163_98173—‐,00.html [accessed May 19].

- Morrow, Betty Hearn . 1999. Identifying and Mapping Community Vulnerability. Disasters 23(1): 1–18. 10.1111/1467-7717.00102. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pedersen, Mogens Jin , and Favero Nathan. 2020. Social Distancing during the COVID‐19 Pandemic: Who Are the Present and Future Noncompliers? Public Administration Review 80(5): 805–14. 10.1111/puar.13240. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pew Research Center . 2020. Health Concerns from COVID‐19 Much Higher among Hispanics and Blacks than Whites. April 14. https://www.people‐press.org/2020/04/14/health‐concerns‐from‐covid‐19‐much‐higher‐among‐hispanics‐and‐blacks‐than‐whites/ [accessed July 28, 2020].

- Powell, John A. 2020. Opinion: Coronavirus Is Not the “Great Equalizer” Many Say It Is. East Bay Times , April 16. https://www.eastbaytimes.com/2020/04/16/opinion‐coronavirus‐is‐not‐the‐great‐equalizer‐many‐say‐it‐is/?mc_cid=b9a8355a54&mc_eid=8bf296b3a1 [accessed July 28, 2020].

- Powell, John A. , Menendian Stephen, and Ake Wendy. 2019. Targeted Universalism: Policy & Practice. Haas institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, May. https://www.socalgrantmakers.org/sites/default/files/resources/targeted_universalism_primer.pdf [accessed July 28, 2020].

- Pulido, Laura . 2000. Rethinking Environmental Racism: White Privilege and Urban Development in Southern California. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 90(1): 12–40. [ Google Scholar ]

- Roberts, Alasdair . 2020. The Third and Fatal Shock: How Pandemic Killed the Millennial Paradigm. Public Administration Review 80(4): 603–9. 10.1111/puar.13223. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Starke, Anthony M., Jr. 2020. Poverty, Policy, and Federal Administrative Discourse: Are Bureaucrats Speaking Equitable Antipoverty Policy Designs into Existence? Public Administration Review. Published online May 5. 10.1111/puar.13191. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stivers, Camilla . 2007. So Poor and So Black: Hurricane Katrina, Public Administration, and the Issue of Race.” Special issue,. Public Administration Review 67: 48–56. 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00812.x. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Taylor, Keeanga‐Yamahtta . 2020. The Black Plague. New Yorker , April 16. https://www.newyorker.com/news/our‐columnists/the‐black‐plague [accessed July 28, 2020].

- U.S. Census Bureau . n.d. QuickFacts: United States. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219 [accessed May 1, 2020].

- Wolfe, Jan . 2020. “African Americans More Likely to Die from Coronavirus Illness, Early Data Shows.” Reuters. April 30, 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us‐health‐coronavirus‐usa‐race‐idUSKBN21O2B6 .

- Wright, James, II , and Merritt Cullen. 2020. Social Equity and COVID‐19: The Case of African Americans. Public Administration Review 80(5): 820–26. 10.1111/puar.13251. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zephyrin, Laurie . 2020. “COVID‐19 More Prevalent, Deadlier in U.S. Counties with Higher Black Populations,” To the Point (blog), Commonwealth Fund, Apr. 23, 2020. 10.26099/y3xs-qr19. [ DOI ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (470.7 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Applications are open

- Skip to content

- Skip to search

- Accessibility Policy

- Report an Accessibility Issue

COVID-19 and the Disproportionate Impact on Black Americans

Q&A with Enrique Neblett

Professor of health behavior and health education.

July 1, 2020

Why is the coronavirus pandemic causing Black Americans to be disproportionately affected by COVID-19 and what can we do at the individual and community level to dismantle the systemic racism at the root of these health disparities? We spoke to Enrique Neblett, professor of Health Behavior and Health Education, to learn more.

In what ways has the Black population in the United States been uniquely affected by COVID-19?

There are a few ways in which people have talked about how Black Americans have been affected by the pandemic.

One has to do with higher rates of hospitalization, infections and mortality rates. From very early on in the pandemic, we were appalled by data that showed Black Americans disproportionately represented for these outcomes relative to their percentage of the population.

Milwaukee and Chicago are two examples that come to mind. African Americans in these cities are about a third of the population, but represented over 70% of the deaths. Similarly, in Georgia, African Americans make up a third of the population but represented 80% of hospitalizations. Unfortunately, we see the same things here in Michigan, where African Americans are roughly 14% of the population, yet they represent 33% of the cases, and 41% of deaths.

The second area is the psychological impact of the pandemic. The Black population is among a large group of the essential workers, and many have to make tough decisions with regard to staying home if they get sick or risking lost wages—or even unemployment—in addition to situations such as having to deal with the loss of family members or taking care of family who may be sick. A recent poll found that Black Americans are nearly three times as likely to personally know someone who has died from the virus than white Americans. In some cases, we’re talking about the emotional toll of having to make excruciating decisions about whether to risk getting sick or work while sick and other financial considerations, while also coping with premature and unexpected death and loss.

Why is COVID-19 impacting the Black population disportionately?

There are a complex set of factors that account for why the pandemic is disproportionately affecting Black Americans, but it is important that we name structural and systemic racism as drivers of COVID-19 disparities. There was speculation early on in the pandemic about chronic underlying conditions and how some are more likely to succumb to COVID-19 when they have diabetes or other underlying conditions. Unfortunately, we know that Black Americans are more likely to have high rates of cardiovascular disease and other chronic conditions than whites, in part, due to structural inequities in access to critical resources necessary to maintain health.

Another factor is occupational vulnerability. Black Americans are more likely than white Americans to hold jobs that are essential to the function of critical infrastructure. These are jobs that require continuous interaction with the public and, in some cases, don’t offer benefits such as paid vacation or the option to work from home.

Availability and access to testing is another important factor. In the initial stages of the pandemic, there were many places where testing was limited or unavailable, or there were significant delays in processing the test results. Lack of access to adequate testing and timely results can both be liabilities in getting urgent and needed medical care.

Poverty is another social determinant of health, structured by institutional and systemic racism, that has played a role in COVID-19 disparities. Lack of access to medical care to seek treatment, quality health insurance, healthy food, standard housing, and clean water are all factors that can indirectly contribute to heightened vulnerability to exposure and infection and lead to negative COVID-19 outcomes.

It is critical that we take a close look at how racism and longstanding structural inequities and practices—past and present—shape these factors and contribute to negative COVID-19 outcomes.

If systemic racism is the root cause of COVID-19 related and other health disparities, how do we need to work together to end it?

There are several strategies that can be mobilized in working against systemic racism and, in turn, the impact of COVID-19 on Black Americans. A multi-pronged approach must inform the action steps that we can take as individuals and communities.

Listening to one another, self-educating, reading, and learning about systemic racism and how it operates are a great start. At the individual level, I’ve also seen people using their voices and privilege to raise awareness and propose concrete actions for eradicating racism by writing op-eds, letters, and making phone calls to lawmakers. Community groups and organizations possess valuable knowledge and expertise, represent critical assets, and are also well positioned to write letters and make calls.

Other strategies for mobilizing include investing in capacity building and helping communities to build their infrastructure in order to be able to respond to disasters like COVID-19.

I've been really fortunate in my role as associate director of the Detroit Community-Academic Urban Research Center (Detroit URC) to discuss mobilization efforts with community partners in Detroit. It’s important that we work together to share resources and information with the residents who need them most. Also, it is important to remember that eradicating racism and promoting health equity will require the execution of concrete, specific and measurable actions that will lead to lasting systemic and structural change.

- Listen to Enrique Neblett on the Population Healthy podcast.