Malle, B. F. \(2011\). Attribution theories: How people make sense of behavior. In Chadee, D. \(Ed.\), Theories in social psychology \(p\ p. 72-95\). Wiley-Blackwell.

These are uncorrected proofs, differing in details from the final published version.

Symbolic Interactionism Theory & Examples

Charlotte Nickerson

Research Assistant at Harvard University

Undergraduate at Harvard University

Charlotte Nickerson is a student at Harvard University obsessed with the intersection of mental health, productivity, and design.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

Key Takeaways

- Symbolic interactionism is a social theoretical framework associated with George Herbert Mead (1863–1931) and Max Weber (1864-1920).

- It is a perspective that sees society as the product of shared symbols, such as language. The social world is, therefore, constructed by the meanings that individuals attach to events and social interactions, and these symbols are transmitted across the generations through language.

- A central concept of symbolic interactionists is the Self , which allows us to calculate the effects of our actions.

- Symbolic interactionism theory has been criticized because it ignores the emotional side of the Self as a basis for social interaction.

Definition and Key Principles

Symbolic interactionism theory assumes that people respond to elements of their environments according to the subjective meanings they attach to those elements, such as meanings being created and modified through social interaction involving symbolic communication with other people.

Symbolic Interactionism is a theoretical framework in sociology that describes how societies are created and maintained through the repeated actions of individuals (Carter and Fuller, 2015).

In simple terms, people in society understand their social worlds through communication — the exchange of meaning through language and symbols.

Instead of addressing how institutions objectively define and affect individuals, symbolic interactionism pays attention to these individuals’ subjective viewpoints and how they make sense of the world from their own perspective (Carter and Fuller, 2015).

The objective structure of a society is less important in the symbolic interactionist view than how subjective, repeated, and meaningful interactions between individuals create society. Thus, society is thought to be socially constructed through human interpretation.

According to Blumer (1969), social interaction thus has four main principles:

- Individuals act in reference to the subjective meaning objects have for them. For example, an individual who sees the “object” of family as being relatively unimportant will make decisions that deemphasize the role of family in their lives;

- Interactions happen in a social and cultural context where objects, people, and situations must be defined and characterized according to individuals’ subjective meanings;

- For individuals, meanings originate from interactions with other individuals and with society;

- These meanings that an individual has are created and recreated through a process of interpretation that happens whenever that individual interacts with others.

The first person to write about the principles underlying Symbolic Interactionism was George Herbert Mead (1934). Mead, an American philosopher, argued that people develop their self-image through interactions with other people.

In particular, Mead concentrated on the language and other forms of talk that happens between individuals. The “ self ” — a part of someone’s personality involving self-awareness and self-image — originates in social experience.

Charles Horton Cooley (1902) used the term looking-glass self to convey the idea that a person’s knowledge of their self-concept is largely determined by the reaction of others around them. Other people thus act as a “ looking-glass ” (mirror) so that we can judge ourselves by looking “in” it.

An individual can respond to others’ opinions about himself and internalize the opinions and feelings that others have about him.

Beginning in the 1960s, sociologists tested and adopted Mead’s ideas.

There are three main schools of Symbolic Interactionism: the Chicago School, the Iowa School, and the Indiana School. These schools stem from the work of Herbert Blumer, Manford Kuhn, and Sheldon Stryker, respectively.

Blumer’s Chicago School of Symbolic Interactionism

Blumer invented the term “Symbolic Interactionism” and created a theory and methodology to test Mead’s ideas. Most sociologists follow the work of Blumer (Carter and Fuller, 2015).

Blumer emphasizes how the self can emerge from the interactive process of joining action (Denzin, 2008; Carter and Fuller, 2015). Humans constantly engage in “mindful action” that constructs and negotiates the meaning of situations.

According to Blumer (1964), all studies of human behavior must begin by studying how people associate and interact with each other rather than treating the individual and society as entirely separate beings (Meltzer and Petras, 1970; Carter and Fuller, 2015).

Society itself is not a structure but a continual process of debating and reinventing the meaning of actions. An action that has a meaning in one context, or in the interaction between any two individuals, can have a completely different meaning between two different individuals or in another context.

Society is about as structured as individuals’ interactions among themselves (Collins, 1994).

Because meaning is constructed through the interactions between individuals, meaning cannot be fixed and can even vary for the same individual.

People who perform actions attach meanings to objects, and their behavior is a unique way of reacting to their interpretation of a situation (Carter and Fuller, 2015).

There is no way to describe how people will generally respond to a situation because every interaction an individual has with an object, situation, or somebody else is different. This is why, according to Blumer, behavior is changing, unpredictable, and unique.

To summarize Blume’s view on Symbolic Interactionism (Blumer, 1969), people act toward objects in a way that reacts to the meanings they have personally given to the objects.

This means that people are reacting to comments from the social interactions that they have with others, and meanings are confronted and modified through a continuous interpretive process that the person uses whenever they deal with things that they encounter (Carter and Fuller, 2015).

Blumer strongly believed that the idea that science was the only right vehicle for discovering truth was deeply flawed. Because all behavior happens on the basis of an individual’s own meanings about the world, Blumer believed that observing general behavioral patterns was not conducive to scientific insight (Carter and Fuller, 2015).

Rather, Blumer aimed to attempt to see how any given person sees the world.

Methodologically, this means that Blummer believed that it is the researcher’s obligation to take the stance of the person they are studying and use the actor’s own categorization of the world to capture how that actor creates meanings from social interactions (Carter and Fuller, 2015).

Iowa School of Symbolic Interactionism

Blumer’s de-emphasis on logical and empirical ways of measuring human behavior provoked responses from theorists who wanted to create a rigorous system of techniques for examining human behavior.

Notably, Manford Kuhn (the Iowa School) and Sheldon Stryker (the Indiana School) used empirical methods to study the self and social structure (Kuhn, 1964; Stryker, 1980; Carter and Fuller, 2015).

To Kuhn, behavior was “purposive, socially constructed, coordinated social acts informed by preceding events in the context of projected acts that occur.” Social interaction can be studied in a way that emphasizes the interrelatedness of an individual’s intention, sense of time, and the ways that they correct their own systems of meanings.

Small groups — groups with, for example, two or three people — to Kuhn, are the focus of most social behavior and interaction.

Social behavior can be studied both in the greater world and within the confines of a laboratory, and this combination of approaches can lead to being able to identify abstract laws for social behavior that can apply to people at university.

And lastly, sociologists must create a systematic and rigorous vocabulary to deconstruct and create a system of cause and effect for how people form meaning through social interactions than social psychologists had before (Carter and Fuller, 2015).

One example of how Kuhn’s methodology deeply contrasts with that of Blumer’s is the Twenty Statements Test.

In the Twenty Statements Test, Kuhn asked participants to respond to the question, “Who am I?” by writing 20 statements about themselves on 20 numbered lines.

Researchers could then code these responses systematically to find how individuals think about their identity and social status in both “conventional” (e.g., as a mother, spouse, or teacher) and idiosyncratic ways while still allowing for enough freedom for researchers to discern how individuals interpret meanings in their world (Carter and Fuller, 2015).

Indiana School of Symbolic Interactionism

In contrast to Kuhn, Stryker of the Indiana School of Symbolic Interactionism emphasizes that the meanings that individuals form from their interactions with others lead to patterns that create and uphold social structures (Carter and Fuller, 2015).

In particular, Stryker focuses on Mead’s concept of roles and role-taking. A social role is a certain set of practices and behaviors taken on by an individual, and these practices and behaviors are regulated through the social situations where the individual takes on the role (Casino and Thien, 2009).

The roles that individuals have are attached to individuals’ positions in society, and they can be predictors of their future behavior.

To Stryker, the social interactions between individuals — socialization — is a process through which individuals learn the expectations for the practices and behaviors of the roles that they have taken on.

Individuals identify themselves by the roles they take in social structure and the beliefs and opinions that others’ identify them with become internalized.

These internalized expectations of how someone with a particular set of roles is supposed to behave become an identity (Carter and Fuller, 2015).

In contrast to the Chicago and the Iowan schools of Symbolic Interactionism, the Indiana school attempts to bridge how people form a sense of meaning and identity on an individual level with the roles that they fill in the greater society.

Examples & Implications

Politics and identity.

In a classic symbolic interactionist study, Brooks (1969) reveals how different self-views correlate with right or left-wing political beliefs. Brooks describes these political beliefs as political roles.

Traditionally, sociologists viewed social beliefs and ideology as a result of economic class and social conditions, but Brooks noted that empirical research up to the 1960s considered political beliefs to be a manifestation of personality.

To symbolic interactionists such as Brooks, political beliefs can be seen as a manifestation of the norms and roles incorporated into how the individual sees themselves and the world around them, which develops out of their interactions with others, wherein they construct meanings.

A political ideology, according to Brooks, is a set of political norms incorporated into the individual’s view of themselves.

Although people may have political roles, these are not necessarily political ideologies — for example, for some in the United States who are apathetic about politics, political beliefs play at most a peripheral role in comparison to the others that they take on, while for others — say activists or diplomats — it plays the central role in their lives.

Brooks hypothesized that those with right-wing political views viewed their sense of self as originating within institutions.

To these people, identity centers around roles within conventional institutions such as family, church, and profession, and other roles are peripheral to the ones they hold in these institutions.

Left-wingers, conversely, identify themselves as acting against or toward traditional institutions. All in all, according to Brook, those with left-wing ideologies identify themselves through a broader range of central statuses and roles than those belonging to the right-wing (Brooks, 1969).

Brooks interviewed 254 individuals who, for the most part, voted regularly, contributed money to political causes, attended political meetings, read the news, and defined themselves as having a strong interest in politics.

He then used a scale to observe and measure how the participants saw themselves in their political roles (asking questions about, for example, contentious political policy).

He then used Kuhn’s Twenty Statements Test to measure how individuals identified conventionally within institutions and idiosyncratically.

All in all, Brooks found that confirming his hypothesis, most left-wing ideologies included fewer descriptions of traditional institutions in their self-definition than average, and most right-wing ideologies included more descriptions of institutions in their self-definition than average.

Not only did this provide evidence for how people formed identities around politics, but Brook’s study provided a precedent for quantifying and testing hypotheses around symbolic interaction (1969).

For this reason, The Self and Political Role is often considered to be a classic study in the Iowa school of Symbolic Interactionism (Carter and Fuller, 2015).

According to West and Zimmerman’s (1987) Doing Gender , the concepts of masculinity and femininity are developed from repeated, patterned interaction and socialization.

Gender, rather than an internal state of being, is a result of interaction, according to symbolic interactionists (Carter and Fuller, 2015).

In order to advance the argument that gender is a “routine, methodical, and reoccurring accomplishment,” West and Zimmerman (1987) take a critical examination of sociological definitions of gender.

In particular, they “contend that the notion of gender as a role obscures the work that is involved in producing gender in everyday activities.” Children are born with a certain sex and are put into a sex category.

Gender is then determined by whether or not someone performs the acts associated with a particular gender. Gender is something that is done rather than an inherent quality of a person.

West and Zimmerman analyze Garfinkel’s (1967) study of Agnes, a transgender woman.

Agnes was born with male genitalia and had reconstructive surgery. When she transitioned, West and Zimmerman argued she had to pass an “if-can” test.

If she could be seen by people as a woman, then she would be categorized as a woman. In order to be perceived as a woman, Agnes faced the ongoing task of producing configurations of behavior that would be seen by others as belonging to a woman.

Agnes constructed her meaning of gender (and consequently her self-identity and self-awareness of gender) by projecting typically feminine behavior and thus being treated as if she were a woman (West and Zimmerman, 1987).

Although few geographers would call themselves symbolic interactionists, geographers are concerned with how people form meanings around a certain place.

They are interested in mundane social interactions and how these daily interactions can lead people to form meanings around social space and identity.

This can extend to both the relationships between people and those between people and non-human entities, such as nature, maps, and buildings.

Early geographers suggested that how people imagined the world was important to their understanding of social and cultural worlds (Casino and Thien, 2020).

In the 1990s, geography shifted to the micro-level, focusing — in a similar vein to Symbolic Interactionism — on interviews and observation.

Geographers who are “post-positivist” — relying primarily on qualitative methods of gathering data — consider the relationships that people have with the places they encounter (for example, whether or not they are local to that place).

These relationships, Casino and Thien (2020) argue, can happen both between people and other people in a place and between people and objects in their environment.

The Self and Identity Formation

A large number of social psychologists have applied the symbolic interactionist framework to study the formation of self and identity.

The three largest theories to come out of these applications of Symbolic Interactionism are role theory, Affect Control Theory, and identity theory. Role theory deals with the process of creating and modifying how one defines oneself and one’s roles (Turner, 1962).

Meanwhile, Affect Control Theory attempts to predict what individuals do when others violate social expectations. According to Affect Control Theory, individuals construct events to confirm the meanings they have created for themselves and others.

And lastly, identity theory aims to understand how one’s identities motivate behavior and emotions in social situations.

For example, Stryker et al. studied how behavior is related to how important certain identities someone has are in relation to other identities (Carter and Fuller, 2015).

For example, someone who identifies heavily with a religious identity is more likely to go to religious services than someone who does not (Stryker and Serpe, 1982).

Architecture

Mead (2015) has long posited that people can form identities from the interactions between non-human objects and themselves as much as from their interactions with other humans.

One such example of sociologists studying how the interactions between non-humans and humans form identity applies to architecture.

Smith and Bugni (2011) examined architectural sociology, which is the study of how socio-cultural phenomena influence and are influenced by the designed physical environment.

This designed physical environment can be as far-ranging as buildings, such as houses, churches, and prisons; bounded spaces, such as streets, plazas, and offices; objects, such as monuments, shrines, and furniture; and many elements of architectural design (such as shapes, size, location, lighting, color, texture, and materials).

Smith and Bugni proposed that symbolic interaction theory is a useful lens to understand architecture for three reasons.

First of all, designed physical environments can influence people’s perception of self, and people can express and influence themselves through designed physical environments.

Secondly, designed physical environments contain and communicate a society’s shared symbols and meanings (Lawrence and Low, 1990).

Thirdly, the designed physical environment is not merely a backdrop for human behavior but an agent to shape thoughts and actions through self-reflection (Smith and Bugni, 2011).

Rather than forcing behavior, architecture suggests possibilities, channels communication, and provides impressions of acceptable activities, networks, norms, and values to individuals (Ankerl, 1981).

People’s interactions with architectural forms can influence, rather than determine, thoughts and actions.

The definition of deviance is relative and depends on the culture, time period, and situation. Howard Becker’s labeling theory (1963) proposes that deviance is not inherent in any act, belief, or condition; instead, it is determined by the social context.

Edwin Sutherland’s differential association theory (Sutherland 1939; Sutherland et al. 1992) asserts that we learn to be deviant through our interactions with others who break the rules.

Ankerl, G. (1981). Experimental Sociology of Architecture: A Guide to Theory. Research and Literature, New Babylon: Studies in the Social Sciences, 36.

Blumer, H. (1986). Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method: Univ of California Press.

Brooks, R. S. (1969). The self and political role: A symbolic interactionist approach to political ideology. The Sociological Quarterly, 10(1), 22-31.

Carter, M. J., & Fuller, C. (2015). Symbolic interactionism . Sociopedia. isa, 1(1), 1-17.

Collins, R. (1994). The microinteractionist tradition. Four sociological traditions, 242-290.

Cooley, C. H. (1902). Looking-glass self. The production of reality: Essays and readings on social interaction, 6, 126-128.

Del Casino, V. J., & Thien, D. (2009). Symbolic interactionism. In International encyclopedia of human geography (pp. 132-137): Elsevier Inc. Denzin, N. K. (2008). Symbolic interactionism and cultural studies: The politics of interpretation: John Wiley & Sons.

Garfinkel, H. (1967). Ethnomethodology. Englewood Cliffs.

Kuhn, M. H. (1964). Major trends in symbolic interaction theory in the past twenty-five years. The Sociological Quarterly, 5(1), 61-84.

Lawrence, D. L., & Low, S. M. (1990). The built environment and spatial form. Annual review of anthropology, 19(1), 453-505.

Mead GH. 1934. Mind, Self, and Society . Chicago: Univ. Chicago Press

Meltzer, B. N., & Petras, J. W. (1970). The Chicago and Iowa schools of symbolic interactionism. Human nature and collective behavior, 3-17. Smith, R. W., & Bugni, V. (2006). Symbolic Interaction Theory and Architecture. Symbolic Interaction, 29(2), 123-155.

Stryker, S. (1980). Symbolic interactionism: A social structural version: Benjamin-Cummings Publishing Company.

Stryker, S., & Serpe, R. T. (1982). Commitment, identity salience, and role behavior: Theory and research example. In Personality, roles, and social behavior (pp. 199-218): Springer.

Turner, R. H. (1962). Role taking: Process versus conformity. Life as theater: A dramaturgical sourcebook, 85-98.

West, C., & Zimmerman, D. H. (1987). Doing gender. Gender & society, 1(2), 125-151.

Further Information

- Aksan, N., Kısac, B., Aydın, M., & Demirbuken, S. (2009). Symbolic interaction theory. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 1(1), 902-904.

- Basic Concepts of Symbolic Interactionism

- Courses Figures of Speech Parts of Speech Academic Writing Linguistics NLP Social Psychology Careers Soft Skills Effective Listening Organizational Behavior Organizational Communication Public Administration

Attribution

- Article's photo | Credit ProProfs

Have you ever wondered why your colleague was late for a meeting? Did they simply oversleep, or was there something more underlying the tardiness? Understanding the reasons behind people's actions is a fundamental human drive, and this quest for explanation lies at the heart of attribution .

The Art of Unraveling Why We Do What We Do

Attribution is the process of inferring the causes of behavior and events. We constantly make these attributions, forming judgments about ourselves, others, and the world around us. These judgments shape our perceptions, emotions, and ultimately, our interactions with the world.

Attribution , in its simplest form, refers to the process of figuring out the causes of our own and others' behavior. We constantly analyze information to discern whether internal factors (personality traits, abilities, motives) or external factors (situational demands, environmental influences) played a bigger role in a particular action.

When someone is late for a meeting, we instinctively engage in attribution, attempting to unearth the reasons behind the behavior. Was it a lack of concern or an external factor beyond their control? Strikingly, there exists a tendency to downplay external influences and focus on internal motives. However, attributing lateness to, for instance, a family illness, leads to more tempered inferences compared to attributing it to a lack of care.

Attribution extends beyond mere curiosity about others; it is an endeavor to comprehend the causes that underlie behavior. This process not only aids in understanding the stable traits and disposition of others but also sheds light on our own actions.

The pursuit of accurate knowledge about others goes beyond discerning their current mood; it encompasses understanding the intricacies of behavior, traits, and the driving forces behind them. In the realm of social psychology Opens in new window , the quest is to unravel the complexities of the social world, seeking not just the 'what' but also the 'why' behind human actions.

Social psychologists posit that our inherent interest in understanding causality is a fundamental aspect of our nature. Beyond the mere observation of actions, we yearn to comprehend the motives and reasons that drive behavior.

Attribution is the mechanism through which we navigate this terrain of understanding. It is the deliberate effort to fathom the causes behind others' behavior and, on occasion, our own. The crux of the matter lies in deciphering whether behavior reflects inherent disposition or is molded by situational constraints.

Imagine yourself witnessing a colleague giving a captivating presentation. Did they succeed due to their innate eloquence, meticulous preparation, or maybe a supportive audience? Or perhaps, a nervous cough during a crucial point planted the seed of doubt in your mind, leading you to attribute their success to external factors. This internal debate, this constant search for causality, is the essence of attribution.

Several key features shape how we make these attributions:

- Locus of Causality: This refers to the perceived source of the cause, whether it's internal (within the person) or external (outside the person). Are we attributing the colleague's success to their personality traits (internal) or to the supportive environment (external)?

- Stability: Do we believe the cause is stable over time and across situations (e.g., attributing the colleague's success to their inherent intelligence) or unstable (e.g., attributing it to a particularly lucky day)?

- Controllability: Can the person be held responsible for the cause, or is it beyond their control? Did the colleague's hard work (controllable) lead to their success, or was it pure luck (uncontrollable)?

These features interact in a dynamic dance, influencing our judgments. For example, we're more likely to attribute internal, stable, and controllable causes to our own failures ("I'm just not good at math"), while attributing external, unstable, and uncontrollable causes to the failures of others ("Their presentation was ruined by the projector malfunction").

Now, let's spice up our knowledge with some real-world examples:

The Fundamental Attribution Error:

Remember our colleague's presentation? This common bias makes us overestimate internal factors and underestimate external ones, leading us to judge others harshly. We might attribute their success solely to their traits, overlooking the supportive environment or their meticulous preparation.

The Actor-Observer Bias:

Ever noticed how we tend to attribute our own actions to external factors ("I was tired, that's why I yelled"), while attributing the actions of others to their internal traits ("They're just rude"). This bias reflects our own self-protective tendencies.

Self-Serving Bias:

We all love a bit of self-praise, right? This bias kicks in when we attribute our successes to internal factors and our failures to external ones. Think of acing an exam ("I studied hard, no wonder I did well") versus flunking a test ("The questions were impossible").

Understanding the Power of Schemas

Our understanding of the world isn't a blank slate. We develop schemas, mental frameworks that guide our expectations of how people behave in specific contexts. A friendly greeting at a party is expected, while a loud outburst at a library is jarring. These schemas help us navigate social situations smoothly, but they can also lead to biases if we apply them too rigidly.

Understanding attributions helps us:

- Navigate social interactions more effectively. By recognizing our own biases and those of others, we can communicate and build relationships more authentically.

- Promote self-awareness and personal growth. By understanding the factors influencing our own behavior, we can make conscious choices and strive for self-improvement.

- Develop empathy and understanding. By considering the various factors that might contribute to someone's actions, we can avoid making unfair judgments and foster a more compassionate world.

Attribution is more than just figuring out "why." It's about understanding the complex tapestry of internal and external forces that weave the fabric of human behavior. It's a continuous quest for meaning in the social world, a journey that shapes our interactions and ultimately, ourselves. So, the next time you catch yourself making an attribution, take a moment to pause and analyze the cues at play. You might be surprised at the hidden world your mind just uncovered!

You might also find useful:

- Causal Attribution

- Attribution Errors & Biases

- Fundamental Attribution Error

- Attribution Theory

- Correspondent Inference Theory

- Covariation Theory

- Self Perception Theory

- Adapted from: Social Psychology, Attribution (p. 129-130) By Akbar Husain

Recommended Books to Flex Your Knowledge

Authored by Award-winning teacher and author Jonathan M. Bowman, "Nonverbal Communication: An Applied Approach" teaches students the fundamentals of nonverbal communication.

Explore the essence of facial expressions with "Anatomy of Facial Expressions" by Uldis Zarins. This insightful guide unveils the nuances of the face, differentiating between fake and genuine emotions.

Explore the captivating world of facial anatomy with "The Face: Pictorial Atlas of Clinical Anatomy, KVM, 2nd Edition." This edition is meticulously crafted for students, professionals, and anatomy enthusiasts.

Dive into the science of facial safety with "Facial Danger Zones" by Rod J Rohrich. This book maps out the potential risks in facial procedures, providing indispensable insights for anyone committed to facial aesthetics.

"Facial Expressions" by Mark Simon is an expertly crafted guide that delves into the intricate language of the face, offering a nuanced understanding of expressions and their storytelling power.

'Nonverbal Communication, 2nd Edition' by Judee K Burgoon explore the social and biological foundations of nonverbal communication as well as the expression of emotions, and interpersonal deception.

American Sign Language 101 is ideal for parents of nonverbal children or children with communication impairments (ages 3-6), American Sign Language for Kids offers a simple way to introduce both of you to ASL.

Speed read people, decipher body language, detect lies, and understand human nature. Is it possible to analyze people without them knowing. Yes, it is. Learn the keys to influencing and persuading others.

Eye contact is an important nonverbal social cue because it projects confidence and assertiveness. This book will turn you from that shy guy who rarely makes eye contact to the eye contact guru who makes elders nervous by looking them straight in the..

Module 1: Foundations of Sociology

Symbolic interactionist theory, learning outcomes.

- Summarize symbolic interactionism

- Apply symbolic interactionism

Sociological Paradigm #3: Symbolic Interactionist Theory

Symbolic interactionism is a micro-level theory that focuses on meanings attached to human interaction, both verbal and non-verbal, and to symbols. Communication—the exchange of meaning through language and symbols—is believed to be the way in which people make sense of their social worlds.

Charles Horton Cooley introduced the looking-glass self (1902) to describe how a person’s sense of self grows out of interactions with others, and he proposed a threefold process for this development: 1) we see how others react to us, 2) we interpret that reaction (typically as positive or negative) and 3) we develop a sense of self based on those interpretations. “Looking-glass” is an archaic term for a mirror, so Cooley theorized that we “see” ourselves when we interact with others.

Figure 1. In symbolic interactionism, people actively shape their social world. This image shows janitorial workers on strike in Santa Monica, California. A symbolic interactionist would be interested in the interactions between these protestors and the messages they communicate.

Social scientists who apply symbolic-interactionist thinking look for patterns of interaction between individuals. Their studies often involve observation of one-on-one interactions. For example, while a conflict theorist studying a political protest might focus on class difference, a symbolic interactionist would be more interested in how individuals in the protesting group interact, as well as the signs and symbols protesters use to communicate their message and to negotiate and thus develop shared meanings.

The focus on the importance of interaction in building a society led sociologists like Erving Goffman (1922–1982) to develop a technique called dramaturgical analysis . Goffman used theater as an analogy for social interaction and recognized that people’s interactions showed patterns of cultural “scripts.” Since it can be unclear what part a person may play in a given situation, as we all occupy multiple roles in a given day (i.e., student, friend, son/ daughter, employee, etc.), one has to improvise his or her role as the situation unfolds (Goffman 1958).

Studies that use the symbolic interactionist perspective are more likely to use qualitative research methods, such as in-depth interviews or participant observation, because they seek to understand the symbolic worlds in which research subjects live.

Constructivism is an extension of symbolic interaction theory which proposes that reality is what humans cognitively construct it to be. We develop social constructs based on interactions with others, and those constructs that last over time are those that have meanings which are widely agreed-upon or generally accepted by most within the society.

The main tenets of symbolic interactionism are explained in the following video.

Research done from this perspective is often scrutinized because of the difficulty of remaining objective. Others criticize the extremely narrow focus on symbolic interaction. Proponents, of course, consider this one of its greatest strengths and generally use research methods that will allow extended observation and/or substantive interviews to provide depth rather than breadth. Interactionists are also criticized for not paying enough attention to social institutions and structural constraints. For example, the interactions between a police officer and a Black man are different than the interactions between a police officer and a white man. Addressing systemic inequalities within the criminal justice system, including pervasive racism, is essential for an interactionist understanding of face-to-face interactions.

- Theoretical Perspectives. Authored by : OpenStax CNX. Located at : https://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]:QMRfI2p1@11/Theoretical-Perspectives . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]

- Image of protestors. Authored by : Steve Lyon. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Right_to_protest#/media/File:Janitor_strike_santa_monica.jpg . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Symbolic interactionism | Society and Culture | MCAT | Khan Academy. Provided by : Khan Academy. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ux2E6uhEVk0 . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 5. Perceiving Others

5.2 Inferring Dispositions Using Causal Attribution

Learning Objectives

- Review the fundamental principles of causal attribution.

- Explore the tendency to make personal attributions for unusual events.

- Review the main components of the covariation principle.

- Outline Weiner’s model of success and failure.

We have seen that we use personality traits to help us understand and communicate about the people we know. But how do we know what traits people have? People don’t walk around with labels saying “I am generous” or “I am aggressive” on their foreheads. In some cases, thinking back to our discussions of reputation in Chapter 3, we may learn about a person indirectly, for instance, through the comments that other people make about that person. We also use the techniques of person perception to help us learn about people and their traits by observing them and interpreting their behaviors. If Zoe hits Joe, we might conclude that Zoe is aggressive. If Cejay leaves a big tip for the waitress, we might conclude that he is generous. It seems natural and reasonable to make such inferences because we can assume (often, but not always, correctly) that behavior is caused by personality. It is Zoe’s aggressiveness that causes her to hit, and it is Cejay’s generosity that led to his big tip.

Although we can sometimes infer personality by observing behavior, this is not always the case. Remember that behavior is influenced by both our personal characteristics and the social context in which we find ourselves. What this means is that the behavior we observe other people engaging in might not always be reflective of their personality; instead, the behavior might have been caused more by the situation rather than by underlying person characteristics. Perhaps Zoe hit Joe not because she is really an aggressive person but because Joe insulted or provoked her first. And perhaps Cejay left a big tip in order to impress his friends rather than because he is truly generous.

Because behavior can be influenced by both the person and the situation, we must attempt to determine which of these two causes actually more strongly determined the behavior. The process of trying to determine the causes of people’s behavior is known as causal attribution (Heider, 1958). Because we cannot see personality, we must work to infer it. When a couple we know breaks up, despite what seemed to be a match made in heaven, we are naturally curious. What could have caused the breakup? Was it something one of them said or did? Or perhaps stress from financial hardship was the culprit?

Making a causal attribution can be a bit like conducting a social psychology experiment. We carefully observe the people we are interested in, and we note how they behave in different social situations. After we have made our observations, we draw our conclusions. We make a personal (or internal or dispositional) attribution when we decide that the behavior was caused primarily by the person . A personal attribution might be something like “I think they broke up because Sarah was not committed to the relationship.” At other times, we may determine that the behavior was caused primarily by the situation —we call this making a situational (or external) attribution. A situational attribution might be something like, “I think they broke up because they were under such financial stress.” At yet other times, we may decide that the behavior was caused by both the person and the situation; “I think they broke up because Sarah’s lack of commitment really became an issue once they had financial troubles.”

Making Inferences about Personality

It is easier to make personal attributions in some cases than in others. When a behavior is unusual or unexpected in the particular situation it occurs in, we can more easily make a personal attribution for it. Imagine that you go to a party and you are introduced to Tess. Tess shakes your hand and says, “Nice to meet you!” Can you readily conclude, on the basis of this behavior, that Tess is a friendly person? Probably not. Because the social context demands that people act in a friendly way (by shaking your hand and saying “Nice to meet you”), it is difficult to know whether Tess acted friendly because of the situation or because she is really friendly. Imagine, however, that instead of shaking your hand, Tess ignores you and walks away. In such cases, it is easier in this case to infer that Tess is unfriendly because her behavior is so contrary to what one would expect.

To test this idea, Edward Jones and his colleagues (Jones, Davis, & Gergen, 1961) conducted a classic experiment in which participants viewed one of four different videotapes of a man who was applying for a job. For half the participants, the video indicated that the man was interviewing for a job as a submariner, a position that required close contact with many people over a long period of time. It was clear to the man being interviewed, as well as to the research participants, that to be a good submariner you should be extroverted (i.e., you should enjoy being around others). The other half of the participants saw a video in which the man was interviewing for a job as an astronaut, which involved (remember, this study was conducted in 1961) being in a small capsule, alone, for days on end. In this case, it was clear to everyone that in order to be good astronaut, you should have an introverted personality.

During the videotape of the interview, a second variable was also manipulated. One half of the participants saw the man indicate that he was actually an introvert (he said things such as “I like to work on my own,” “I don’t go out much”), and the other half saw the man say that he was actually an extrovert (he said things such as “I would like to be a salesman,” “I always get ideas from others”). After viewing one of the four videotapes, participants were asked to indicate how introverted or extroverted they thought the applicant really was.

As you can see in Table 5.2, “Attributions to Expected and Unexpected Behaviors,” when the applicant gave responses that better matched what was required by the job (i.e., for the submariner job, the applicant said he was an extrovert, and for the astronaut job, he said he was an introvert), the participants did not think his statements were as indicative of his underlying personality as they did when the applicant said the opposite of what was expected by the job (i.e., when the job required that he be extroverted but he said he was introverted, or vice versa).

The idea here is that the statements that were unusual or unexpected (on the basis of the job requirements) just seemed like they could not possibly have been caused by the situation, so the participants really thought that the interviewee was telling the truth. On the other hand, when the interviewee made statements that were consistent with what was required by the situation, it was more difficult to be sure that he was telling the truth (perhaps, thinking back to the discussion of strategic self-presentation in Chapter 3, he was just saying these things because he wanted to get the job), and the participants made weaker personal attributions for his behavior.

We can also make personal attributions more easily when we know that the person had a choice in the behavior. If a man chooses to be friendly, even in situations in which he might not be, this probably means that he is friendly. But if we can determine that he’s been forced to be friendly, it’s more difficult to know. If, for example, you saw a man pointing a gun at another person, and then you saw that person give his watch and wallet to the gunman, you would probably not infer that the person was generous!

Jones and Harris (1967) had student participants in a study read essays that had been written by other students. Half of the participants thought the students had chosen the essay topics, whereas the other half thought the students had been assigned the topics by their professor. The participants were more likely to make a personal attribution that the students really believed in the essay they were writing when they had chosen the topics rather than been assigned topics.

Sometimes a person may try to lead others to make personal attributions for their behavior to make themselves seem more believable. For example, when a politician makes statements supporting a cause in front of an audience that does not agree with her position, she will be seen as more committed to her beliefs and may be more persuasive than if she gave the same argument in front of an audience known to support her views. Again, the idea is based on principles of attribution: if there is an obvious situational reason for making a statement (the audience supports the politician’s views), then the personal attribution (that the politician really believes what she is saying) is harder to make.

Detecting the Covariation between Personality and Behavior

So far, we have considered how we make personal attributions when we have only limited information; that is, behavior observed at only a single point in time—a man leaving a big tip at a restaurant, a man answering questions at a job interview, or a politician giving a speech. But the process of making attributions also occurs when we are able to observe a person’s behavior in more than one situation. Certainly, we can learn more about Cejay’s generosity if he gives a big tip in many different restaurants with many different people, and we can learn more about a politician’s beliefs by observing the kinds of speeches she gives to different audiences over time.

When people have multiple sources of information about the behavior of a person, they can make attributions by assessing the relationship between a person’s behavior and the social context in which it occurs. One way of doing so is to use the covariation principle, which states that a given behavior is more likely to have been caused by the situation if that behavior covaries (or changes) across situations . Our job, then, is to study the patterns of a person’s behavior across different situations in order to help us to draw inferences about the causes of that behavior (Jones et al., 1987; Kelley, 1967).

Research has found that people focus on three kinds of covariation information when they are observing the behavior of others (Cheng & Novick, 1990).

- Consistency information. A situation seems to be the cause of a behavior if the situation always produces the behavior in the target . For instance, if I always start to cry at weddings, then it seems as if the wedding is the cause of my crying.

- Distinctiveness information. A situation seems to be the cause of a behavior if the behavior occurs when the situation is present but not when it is not present . For instance, if I only cry at weddings but not at any other time, then it seems as if the wedding is the cause of my crying.

- Consensus information. A situation seems to be the cause of a behavior if the situation creates the same behavior in most people . For instance, if many people cry at weddings, then it seems as if the wedding is the cause of my (and the other people’s) crying.

Imagine that your friend Jane likes to go out with a lot of different men, and you have observed her behavior with each of these men over time. One night she goes to a party with Ravi, where you observe something unusual. Although Jane has come to the party with Ravi, she completely ignores him all night. She dances with some other men, and in the end she leaves the party with someone else. This is the kind of situation that might make you wonder about the cause of Jane’s behavior (is she a rude person, or is this behavior caused more by Ravi?) and for which you might use the covariation principle to attempt to draw some conclusions.

According to the covariation principle, you should be able to determine the cause of Jane’s behavior by considering the three types of covariation information: consistency, distinctiveness, and consensus. One question you might ask is whether Jane always treats Ravi this way when she goes out with him. If the answer is yes, then you have some consistency information: the perception that a situation always produces the same behavior in a person. If you have noticed that Jane ignores Ravi more than she ignores the other men she dates, then you also have distinctiveness information: the perception that a behavior occurs when the situation is present but not when it is not present. Finally, you might look for consensus information: the perception that a situation is creating the same response in most people—do other people tend to treat Ravi in the same way?

Consider one more example. Imagine that a friend of yours tells you that he has just seen a new movie and that it is the greatest movie he’s ever seen. As you wonder whether you should make an attribution to the situation (the movie), you will naturally ask about consensus; do other people like the movie too? If they do, then you have positive consensus information about how good the movie is. But you probably also have some information about your friend’s experiences with movies over time. If you are like most people, you probably have friends who love every movie they see. If this is the case for this friend, you probably won’t yet be that convinced that it’s a great movie—in this case, your friend’s reactions would not be distinctive. On the other hand, if your friend does not like most movies he sees but loves this one, then distinctiveness is strong (the behavior is occurring only in this particular situation). If this is the case, then you can be more certain it’s something about the movie that has caused your friend’s enthusiasm. Your next thought may be, “I’m going to see that movie tonight.” You can see still another example of the use of covariation information in Table 5.3, “Using Covariation Information.”

In summary, covariation models predict that we will most likely make external attributions when consensus, distinctiveness, and consistency are all high. In contrast, when consensus and disctinctiveness are both low and this is accompanied by high consistency, then we are most likely to arrive at an internal attribution (Kelley, 1967). In other situations, where the pattern of consensus, consistency, and distinctiveness does not fall into one of these two options, it is predicted that we will tend to make attributions to both the person and the situation.

These predictions have generally been supported in studies of attribution, typically asking people to make attributions about a stranger’s behaviors in vignettes (Kassin, 1979). In studies in more naturalistic contexts, for example those we make about ourselves and others who we know well, many other factors will also affect the types of attributions that we make. These include our relationship to the person and our prior beliefs. For instance, our attributions toward our friends are often more favorable than those we make toward strangers (Campbell, Sedikides, Reeder, & Elliot, 2000). Also, in line with our discussions of schemas and social cogniton in Chapter 2, they are often consistent with the content of the schemas that are salient to us at the time (Lyon, Startup, & Bentall, 1999).

H5P: TEST YOUR LEARNING: CHAPTER 5 FILL IN THE BLANKS – INTERNAL OR EXTERNAL ATTRIBUTION CASE STUDY

Use your understanding of consensus, distinctiveness, and consistency information to determine the type of attribution you would most likely make in the situation below. Fill in each blank with the correct word (low or high for the three types of information; internal or external for the type of attribution).

You are a psychotherapist with many clients. One day, your last client is twenty minutes late for a one hour appointment. He is regularly late for your appointments. Most of your other clients are typically late arriving. He has disclosed to you that, in general, he is quite a punctual person. In this situation, your client’s lateness for his current appointment shows consensus, distinctiveness, and consistency. Given this, it is most likely that you would make an attribution about his behavior.

Attributions for Success and Failure

Causal attribution is involved in many important situations in our lives; for example, when we attempt to determine why we or others have succeeded or failed at a task. Think back for a moment to a test that you took, or another task that you performed, and consider why you did either well or poorly on it. Then see if your thoughts reflect what Bernard Weiner (1985) considered to be the important factors in this regard.

Weiner was interested in how we determine the causes of success or failure because he felt that this information was particularly important for us: accurately determining why we have succeeded or failed will help us see which tasks we are good at already and which we need to work on in order to improve. Weiner proposed that we make these determinations by engaging in causal attribution and that the outcomes of our decision-making process were attributions made either to the person (“I succeeded/failed because of my own personal characteristics”) or to the situation (“I succeeded/failed because of something about the situation”).

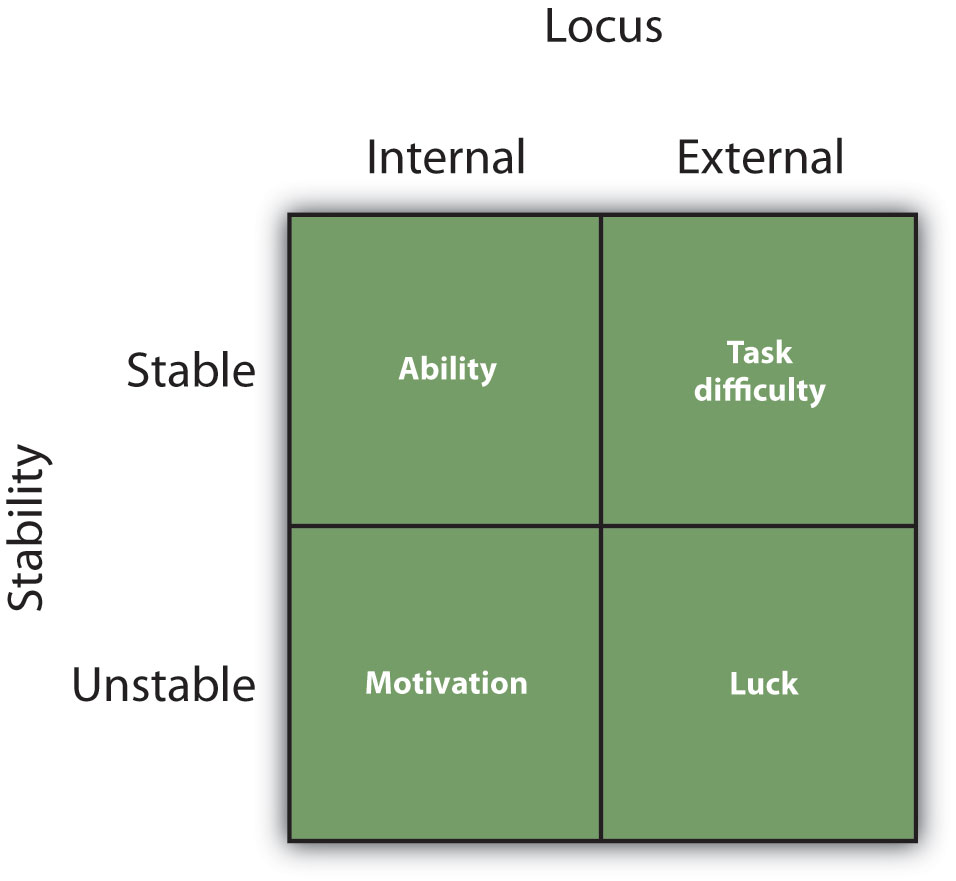

Weiner’s analysis is shown in Figure 5.8, “Attributions for Success and Failure.” According to Weiner, success or failure can be seen as coming from personal causes (e.g., ability, motivation) or from situational causes (e.g., luck, task difficulty). However, he also argued that those personal and situational causes could be either stable (less likely to change over time) or unstable (more likely to change over time).

This figure shows the potential attributions that we can make for our, or for other people’s, success or failure. Locus considers whether the attributions are to the per

son or to the situation, and stability considers whether or not the situation is likely to remain the same over time.

If you did well on a test because you are really smart, then this is a personal and stable attribution of ability . It’s clearly something that is caused by you personally, and it is also quite a stable cause—you are smart today, and you’ll probably be smart in the future. However, if you succeeded more because you studied hard, then this is a success due to motivation . It is again personal (you studied), but it is also potentially unstable (although you studied really hard for this test, you might not work so hard for the next one). Weiner considered task difficulty to be a situational cause: you may have succeeded on the test because it was easy, and he assumed that the next test would probably be easy for you too (i.e., that the task, whatever it is, is always either hard or easy). Finally, Weiner considered success due to luck (you just guessed a lot of the answers correctly) to be a situational cause, but one that was more unstable than task difficulty. It turns out that although Weiner’s attributions do not always fit perfectly (e.g., task difficulty may sometimes change over time and thus be at least somewhat unstable), the four types of information pretty well capture the types of attributions that people make for success and failure.

We have reviewed some of the important theory and research into how we make attributions. Another important question, that we will now turn to, is how accurately we attribute the causes of behavior. It is one thing to believe that that someone shouted at us because he or she has an aggressive personality, but quite another to prove that the situation, including our own behavior, was not the more important cause!

Key Takeaways

- Causal attribution is the process of trying to determine the causes of people’s behavior.

- Attributions are made to personal or situational causes.

- It is easier to make personal attributions when a behavior is unusual or unexpected and when people are perceived to have chosen to engage in it.

- The covariation principle proposes that we use consistency information, distinctiveness information, and consensus information to draw inferences about the causes of behaviors.

- According to Bernard Weiner, success or failure can be seen as coming from either personal causes (ability and motivation) or situational causes (luck and task difficulty).

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- Describe a time when you used causal attribution to make an inference about another person’s personality. What was the outcome of the attributional process? To what extent do you think that the attribution was accurate? Why?

- Outline a situation where you used consensus, consistency, and distinctiveness information to make an attribution about someone’s behavior. How well does the covariation principle explain the type of attribution (internal or external) that you made?

- Consider a time when you made an attribution about your own success or failure. How did your analysis of the situation relate to Weiner’s ideas about these processes? How did you feel about yourself after making this attribution and why?

Allison, S. T., & Messick, D. M. (1985b). The group attribution error . Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 21(6), 563-579.

Campbell, W. K., Sedikides, C., Reeder, G. D., & Elliot, A. J. (2000). Among friends: An examination of friendship and the self-serving bias. British Journal of Social Psychology, 39, 229-239.

Cheng, P. W., & Novick, L. R. (1990). A probabilistic contrast model of causal induction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58 (4), 545–567.

Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations . Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Jones, E. E., & Harris, V. A. (1967). The attribution of attitudes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 3 (1), 1–24.

Jones, E. E., Davis, K. E., & Gergen, K. J. (1961). Role playing variations and their informational value for person perception. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 63 (2), 302–310.

Jones, E. E., Kanouse, D. E., Kelley, H. H., Nisbett, R. E., Valins, S., & Weiner, B. (Eds.). (1987). Attribution: Perceiving the causes of behavior . Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Kassin, S. M. (1979). Consensus information, prediction, and causal attribution: A review of the literature and issues. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 1966-1981.

Kelley, H. H. (1967). Attribution theory in social psychology. In D. Levine (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation (Vol. 15, pp. 192–240). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Lyon, H. M., & Startup, M., & Bentall, R. P. (1999). Social cognition and the manic defense: Attributions, selective attention, and self-schema in Bipolar Affective Disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108(2), 273-282.Frubin

Uleman, J. S., Blader, S. L., & Todorov, A. (Eds.). (2005). Implicit impressions . New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Weiner, B. (1985). Attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92 , 548–573.

Image Description

Figure 5.8 Attributions for Success and Failure

The potential attributions we make for our, or for other people’s, success or failure based on the locus and the stability of the situation

- Ability: internal locus, stable

- Task difficulty: external locus, stable

- Motivation: internal locus, unstable

- Luck: external locus, unstable

[Return to Figure 5.8]

The process of trying to determine the causes of people’s behavior.

When we decide that the behavior was caused primarily by the person.

We may determine that the behavior was caused primarily by the situation.

A given behavior is more likely to have been caused by the situation if that behavior covaries (or changes) across situations.

A situation seems to be the cause of a behavior if the situation always produces the behavior in the target. For instance, if I always start to cry at weddings, then it seems as if the wedding is the cause of my crying.

When the situation is present but not when it is not present.

Creates the same behavior in most people.

Principles of Social Psychology - 1st International H5P Edition Copyright © 2022 by Dr. Rajiv Jhangiani and Dr. Hammond Tarry is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is Behaviorism?

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Classical Conditioning

Operant conditioning, frequently asked questions.

Behaviorism is a theory of learning based on the idea that all behaviors are acquired through conditioning, and conditioning occurs through interaction with the environment . Behaviorists believe that our actions are shaped by environmental stimuli.

In simple terms, according to this school of thought, also known as behavioral psychology, behavior can be studied in a systematic and observable manner regardless of internal mental states. Behavioral theory also says that only observable behavior should be studied, as cognition , emotions , and mood are far too subjective.

Strict behaviorists believe that any person—regardless of genetic background, personality traits , and internal thoughts— can be trained to perform any task, within the limits of their physical capabilities. It only requires the right conditioning.

Verywell / Jiaqi Zhou

History of Behaviorism

Behaviorism was formally established with the 1913 publication of John B. Watson 's classic paper, "Psychology as the Behaviorist Views It." It is best summed up by the following quote from Watson, who is often considered the father of behaviorism:

"Give me a dozen healthy infants, well-formed, and my own specified world to bring them up in and I'll guarantee to take any one at random and train him to become any type of specialist I might select—doctor, lawyer, artist, merchant-chief and, yes, even beggar-man and thief, regardless of his talents, penchants, tendencies, abilities, vocations, and race of his ancestors."

Simply put, strict behaviorists believe that all behaviors are the result of experience. Any person, regardless of their background, can be trained to act in a particular manner given the right conditioning.

From about 1920 through the mid-1950s, behaviorism became the dominant school of thought in psychology . Some suggest that the popularity of behavioral psychology grew out of the desire to establish psychology as an objective and measurable science.

During that time, researchers were interested in creating theories that could be clearly described and empirically measured, but also used to make contributions that might have an influence on the fabric of everyday human lives.

Types of Behaviorism

There are two main types of behaviorism used to describe how behavior is formed.

Methodological Behaviorism

Methodological behaviorism states that observable behavior should be studied scientifically and that mental states and cognitive processes don't add to the understanding of behavior. Methodological behaviorism aligns with Watson's ideologies and approach.

Radical Behaviorism

Radical behaviorism is rooted in the theory that behavior can be understood by looking at one's past and present environment and the reinforcements within it, thereby influencing behavior either positively or negatively. This behavioral approach was created by the psychologist B.F. Skinner .

Classical conditioning is a technique frequently used in behavioral training in which a neutral stimulus is paired with a naturally occurring stimulus. Eventually, the neutral stimulus comes to evoke the same response as the naturally occurring stimulus, even without the naturally occurring stimulus presenting itself.

Throughout the course of three distinct phases of classical conditioning, the associated stimulus becomes known as the conditioned stimulus and the learned behavior is known as the conditioned response .

Learning Through Association

The classical conditioning process works by developing an association between an environmental stimulus and a naturally occurring stimulus.

In physiologist Ivan Pavlov 's classic experiments, dogs associated the presentation of food (something that naturally and automatically triggers a salivation response) at first with the sound of a bell, then with the sight of a lab assistant's white coat. Eventually, the lab coat alone elicited a salivation response from the dogs.

Factors That Impact Conditioning

During the first part of the classical conditioning process, known as acquisition , a response is established and strengthened. Factors such as the prominence of the stimuli and the timing of the presentation can play an important role in how quickly an association is formed.

When an association disappears, this is known as extinction . It causes the behavior to weaken gradually or vanish. Factors such as the strength of the original response can play a role in how quickly extinction occurs. The longer a response has been conditioned, for example, the longer it may take for it to become extinct.

Operant conditioning, sometimes referred to as instrumental conditioning, is a method of learning that occurs through reinforcement and punishment . Through operant conditioning, an association is made between a behavior and a consequence for that behavior.

This behavioral approach says that when a desirable result follows an action, the behavior becomes more likely to happen again in the future. Conversely, responses followed by adverse outcomes become less likely to reoccur.

Consequences Affect Learning

Behaviorist B.F. Skinner described operant conditioning as the process in which learning can occur through reinforcement and punishment. More specifically: By forming an association between a certain behavior and the consequences of that behavior, you learn.

For example, if a parent rewards their child with praise every time they pick up their toys, the desired behavior is consistently reinforced and the child will become more likely to clean up messes.

Timing Plays a Role

The process of operant conditioning seems fairly straightforward—simply observe a behavior, then offer a reward or punishment. However, Skinner discovered that the timing of these rewards and punishments has an important influence on how quickly a new behavior is acquired and the strength of the corresponding response.

This makes reinforcement schedules important in operant conditioning. These can involve either continuous or partial reinforcement.

- Continuous reinforcement involves rewarding every single instance of a behavior. It is often used at the beginning of the operant conditioning process. Then, as the behavior is learned, the schedule might switch to one of partial reinforcement.

- Partial reinforcement involves offering a reward after a number of responses or after a period of time has elapsed. Sometimes, partial reinforcement occurs on a consistent or fixed schedule. In other instances, a variable and unpredictable number of responses or amount of time must occur before the reinforcement is delivered.

Uses for Behaviorism

The behaviorist perspective has a few different uses, including some related to education and mental health.

Behaviorism can be used to help students learn, such as by influencing lesson design. For instance, some teachers use consistent encouragement to help students learn (operant conditioning) while others focus more on creating a stimulating environment to increase engagement (classical conditioning).

One of the greatest strengths of behavioral psychology is the ability to clearly observe and measure behaviors. Because behaviorism is based on observable behaviors, it is often easier to quantify and collect data when conducting research.

Mental Health

Behavioral therapy was born from behaviorism and originally used in the treatment of autism and schizophrenia. This type of therapy involves helping people change problematic thoughts and behaviors, thereby improving mental health.

Effective therapeutic techniques such as intensive behavioral intervention, behavior analysis, token economies, and discrete trial training are all rooted in behaviorism. These approaches are often very useful in changing maladaptive or harmful behaviors in both children and adults.

Impact of Behaviorism

Several thinkers influenced behavioral psychology. Among these are Edward Thorndike , a pioneering psychologist who described the law of effect, and Clark Hull , who proposed the drive theory of learning.

There are a number of therapeutic techniques rooted in behavioral psychology. Though behavioral psychology assumed more of a background position after 1950, its principles still remain important.

Even today, behavior analysis is often used as a therapeutic technique to help children with autism and developmental delays acquire new skills. It frequently involves processes such as shaping (rewarding closer approximations to the desired behavior) and chaining (breaking a task down into smaller parts, then teaching and chaining the subsequent steps together).

Other behavioral therapy techniques include aversion therapy , systematic desensitization , token economies, behavior modeling , and contingency management.

Criticisms of Behaviorism

Many critics argue that behaviorism is a one-dimensional approach to understanding human behavior. They suggest that behavioral theories do not account for free will or internal influences such as moods, thoughts, and feelings.

Freud, for example, felt that behaviorism failed by not accounting for the unconscious mind's thoughts, feelings, and desires, which influence people's actions. Other thinkers, such as Carl Rogers and other humanistic psychologists , believed that behaviorism was too rigid and limited, failing to take into consideration personal agency.

More recently, biological psychology has emphasized the role the brain and genetics play in determining and influencing human actions. The cognitive approach to psychology focuses on mental processes such as thinking, decision-making, language, and problem-solving. In both cases, behaviorism neglects these processes and influences in favor of studying only observable behaviors.

Behavioral psychology also does not account for other types of learning that occur without the use of reinforcement and punishment. Moreover, people and animals can adapt their behavior when new information is introduced, even if that behavior was established through reinforcement.

A Word From Verywell

While the behavioral approach might not be the dominant force that it once was, it has still had a major impact on our understanding of human psychology . The conditioning process alone has been used to understand many different types of behaviors, ranging from how people learn to how language develops.

But perhaps the greatest contributions of behavioral psychology lie in its practical applications. Its techniques can play a powerful role in modifying problematic behavior and encouraging more positive, helpful responses. Outside of psychology, parents, teachers, animal trainers, and many others make use of basic behavioral principles to help teach new behaviors and discourage unwanted ones.

John B. Watson is known as the founder of behaviorism. Though others had similar ideas in the early 1900s, when behavioral theory began, some suggest that Watson is credited as behavioral psychology's founder due to being "an attractive, strong, scientifically accomplished, and forceful speaker and an engaging writer" who was willing to share this behavioral approach when other psychologists were less likely to speak up.

Behaviorism can be used to help elicit positive behaviors or responses in students, such as by using reinforcement. Teachers with a behavioral approach often use "skill and drill" exercises to reinforce correct responses through consistent repetition, for instance.

Other ways reinforcement-based behaviorism can be used in education include praising students for getting the right answer and providing prizes for those who do well. Using tests to measure performance enables teachers to measure observable behaviors and is, therefore, another behavioral approach.

Behaviorism says that behavior is a result of environment, the environment being an external stimulus. Psychoanalysis is the opposite of this, in that it is rooted in the belief that behavior is a result of an internal stimulus. Psychoanalytic theory is based on behaviors being motivated by one's unconscious mind, thus resulting in actions that are consistent with their unknown wishes and desires.

Whereas strict behaviorism has no room for cognitive influences, cognitive behaviorism operates on the assumption that behavior is impacted by thoughts and emotions. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), for instance, attempts to change negative behaviors by changing the destructive thought patterns behind them.

Krapfl JE. Behaviorism and society . Behav Anal. 2016;39(1):123-9. doi:10.1007/s40614-016-0063-8

Abramson CI. Problems of teaching the behaviorist perspective in the cognitive revolution . Behav Sci (Basel). 2013;3(1):55-71. doi:10.3390/bs3010055

Malone JC. Did John B. Watson really "found" behaviorism? . Behav Anal. 2014;37(1):1-12. doi:10.1007/s40614-014-0004-3

Penn State University. Introductory psychology blog (S14)_C .

Moore J. Methodological behaviorism from the standpoint of a radical behaviorist . Behav Anal. 2013;36(2):197-208. doi:10.1007/bf03392306

Rouleau N, Karbowski LM, Persinger MA. Experimental evidence of classical conditioning and microscopic engrams in an electroconductive material . PLoS ONE. 2016;11(10):e0165269. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0165269

Vanelzakker MB, Dahlgren MK, Davis FC, Dubois S, Shin LM. From Pavlov to PTSD: The extinction of conditioned fear in rodents, humans, and anxiety disorders . Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2014;113:3-18. doi:10.1016/j.nlm.2013.11.014

Kehoe EJ. Repeated acquisitions and extinctions in classical conditioning of the rabbit nictitating membrane response . Learn Mem. 2006;13(3):366-75. doi:10.1101/lm.169306

Staddon JE, Cerutti DT. Operant conditioning . Annu Rev Psychol. 2003;54:115-44. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145124

Kaplan D. Behaviorism in online teacher training . Psychol . 2018;9(4):83687. doi:10.4236/psych.2018.94035

Stanford University. Behaviorism .

Smith T. What is evidence-based behavior analysis? . Behav Anal. 2013;36(1):7-33. doi:10.1007/bf03392290

Morris EK, Altus DE, Smith NG. A study in the founding of applied behavior analysis through its publications . Behav Anal . 2013;36(1):73-107. doi:10.1007/bf03392293

Schreibman L, Dawson G, Stahmer AC, et al. Naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions: Empirically validated treatments for autism spectrum disorder . J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45(8):2411-28. doi:10.1007/s10803-015-2407-8

Bower GH. The evolution of a cognitive psychologist: a journey from simple behaviors to complex mental acts. Annu Rev Psychol . 2008;59:1-27. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093722

University of California Berkeley. Behaviorism .

American Psychoanalytic Association. About psychoanalysis .

Mills JA. Control: A History of Behavioral Psychology . New York University Press.

Skinner BF. About Behaviorism . Alfred A. Knopf.

Watson JB. Behaviorism . Transaction Publishers.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

What the two meanings have in common is a process of assigning: in attribution as explanation, a behav-ior is assigned to its cause; in attribution as inference, a quality or attribute is assigned to the agent on the basis of an observed behavior.

In social psychology, attribution is the process of inferring the causes of events or behaviors. In real life, attribution is something we all do every day, usually without any awareness of the underlying processes and biases that lead to our inferences.

Symbolic interactionism theory assumes that people respond to elements of their environments according to the subjective meanings they attach to those elements, such as meanings being created and modified through social interaction involving symbolic communication with other people.

It just means that various approaches exist to understanding, explaining, and predicting how people think and act. There are five major types of psychological theories: behavioral, cognitive, humanistic, psychodynamic, and biological. Let's take a closer look at each of these psychological theories and how they work. Behavioral Theories.

Attribution is defined by Westen (1999) as the process of making an inference about the causes of people’s mental states or behaviors. In daily life, people meditate on and explore the causes of their own and other people’s behaviors and psychological states.