Masterpiece Story: An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump by Joseph Wright of Derby

Maya M. Tola 5 January 2024 min Read

Joseph Wright of Derby, An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump , ca 1768, National Gallery, London, UK.

Recommended

European Art

Joseph Wright of Derby: Painting the Industrial Revolution

Artists and Industrial Revolution: Images of the Changing World

Romanticism

Enlightenment and Joseph Wright ‘of Derby’

An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump is not only a masterpiece from the Age of Enlightenment but also a monumental artistic achievement of Joseph Wright of Derby . Completed in 1768, this is a large artwork that depicts an experiment portraying the effects of reducing the pressure of the air on the bird enclosed within. This experiment was described by 17th-century chemist, Robert Boyle in his landmark book New Experiments Physico-Mechanicall, Touching the Spring of the Air, and its Effects .

Joseph Wright of Derby, Self-Portrait , ca. 1780, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, CT, USA.

- Joseph Wright of Derby

Joseph Wright of Derby was an English painter noted for his landscapes and portraitures. He showed an early affinity for painting that was honed under the tutelage of elite London-based painter, Thomas Hudson. Wright became known for his use of the tenebrism effect, a style of painting with pronounced chiaroscuro that emphasizes the contrasts between light and dark.

In addition to his artistic acumen, Wright had a curious mind and took a keen interest in science and natural philosophy. He was a member of the Lunar Society, a club of learned members of society located in and around, Birmingham, UK. Aside from his usual body of work, Wright utilized the canvas to depict scientific topics from the Age of Enlightenment. An Experiment on a Bird in an Air Pump from the National Gallery in London evidences an intersection between his two great passions, art and scientific inquiry.

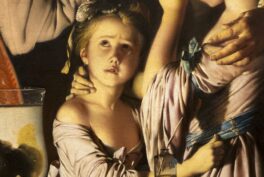

Joseph Wright of Derby, An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump , ca 1768, National Gallery, London, UK. Detail.

Air Pump Experiments

Air pumps or vacuum pumps were a common scientific tool employed by lecturers in natural philosophy. Lecturers conducted theatrical demonstrations, sometimes for private audiences in their homes. Onlookers were enlightened as to the importance of air to living beings by the evacuation of air from the vessel within which an animal or bird was contained. The “animal in the air pump” experiments were often the centerpiece of their demonstration.

The Audience

Wright illustrated a group of ten people gathered around a table with an air pump that has been rendered in exquisite detail. Other devices and paraphernalia are scattered across a table with a varied group of onlookers. The group of spectators displays a wide variety of reactions that range from fascination to utter dismay. The couple on the left is in the middle of an amorous exchange and perhaps not as engaged in the demonstration. In contrast, the two figures that appear below them are in rapt attention of the fate of the bird.

The central figure is an older lecturer who is conducting the experiment. He looks straight out of the painting as if he is inviting participation or questions. Another participant across the table appears either lost in thought or completely engaged in the experiment and oblivious to the despair of the two young girls beside them.

The emotional reaction of the young girls in this painting is palpable. They do not share scientific curiosity and are upset by the plight of the bird even as they are consoled by their father. The grey cockatiel contained within the vessel flutters in panic as the air is withdrawn by the pump.

The figures in the painting were never identified and there is no conclusive evidence to imply that the painting was based on real people.

Illumination

Another striking feature of this painting is the unseen source of illumination located behind the glass goblet. The illumination, possibly a candle, produces strong patterns of soft but brilliant light dispersed through the bowl and contrasts with the dark shadows. A secondary source of illumination is the full moon that appears behind the young assistant who is either opening or closing the window. The moon is a reference to Wright’s participation in the Lunar Society of Birmingham.

Revered Depiction

Despite the barbaric nature of the experiment to current sensitivities, in the 18th-century context, this was a celebration of human enlightenment and advancement in the field of scientific curiosity. It was a revered depiction that was rendered in layout typically reserved in the depiction of religious imagery or historical themes during the Renaissance. Wright utilized dramatic chiaroscuro in the manner and style of Caravaggio to highlight the subliminal aspect of his work. Wright was widely recognized by his contemporaries for his exceptional work, however, his style and subjects were provincial and were not widely imitated.

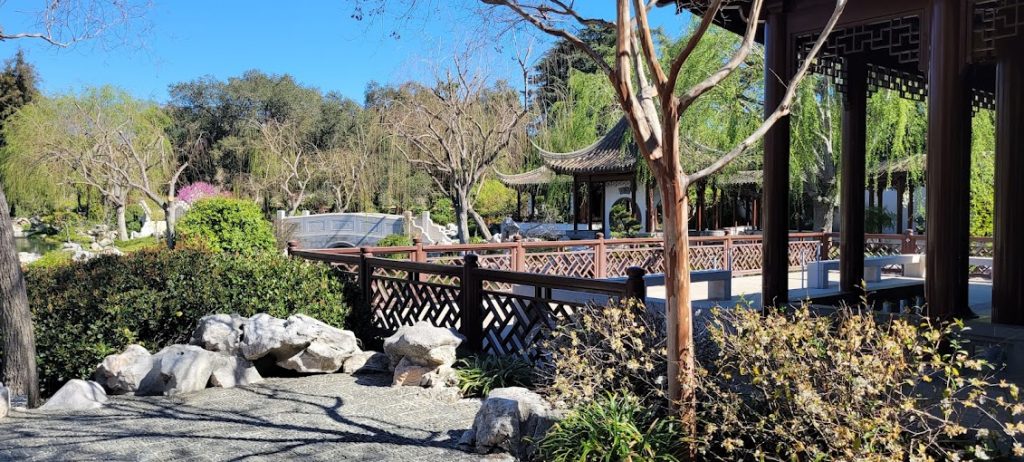

The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, March 2022, Los Angeles, CA, USA. Photo by the author.

Science and the Sublime Exhibit

The Science and the Sublime 2022 exhibit was the result of a reciprocal art exchange between the National Gallery in London and The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, in Los Angeles. Other items from the exhibit included several other artworks from The Huntington’s own collections, including Vesuvius from Portici by Joseph Wright and other rare books from the Huntington Library that contain related scientific and moral discussions.

Get your daily dose of art

Click and follow us on Google News to stay updated all the time

We love art history and writing about it. Your support helps us to sustain DailyArt Magazine and keep it running.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!

Maya M. Tola

Maya Tola is a Dallas-based attorney, with a zest for art history. A time traveler at heart, Maya often finds herself consumed in the contemplation of life in antiquity. She has been sharing her infectious enthusiasm for art and history since 2018 through her posts and articles for the DailyArt App and DailyArt Magazine. When she's not working or writing, you'll find Maya obsessing over plants, animals, and food (in no particular order).

Proofreader Adam Robinson

Masterpiece Story: The Phoenix Portrait of Elizabeth I

One of the most famous depictions of Elizabeth I is Nicholas Hilliard’s Phoenix Portrait, depicting the Queen with a pendant shaped like a mythical...

Guest Profile 5 December 2024

Masterpiece Story: Wheatfield with Cypresses by Vincent van Gogh

Wheatfield with Cypresses expresses the emotional intensity that has become the trademark of Vincent van Gogh’s signature style. Let’s delve...

James W Singer 17 November 2024

Masterpiece Story: Young Bacchus by Mary Beale

Mary Beale is a rarity: a prolific, well-documented, successful, 17th-century woman artist. Her painting of Young Bacchus perfectly illustrates how...

Catriona Miller 10 November 2024

Faith Ringgold, Sunflowers, and Van Gogh

Faith Ringgold’s The Sunflower Quilting Bee at Arles is part of the artist’s series of mixed media works titled The French Collection, in which...

Aniela Rybak-Vaganay 25 November 2024

Never miss DailyArt Magazine's stories. Sign up and get your dose of art history delivered straight to your inbox!

An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump

Catalogue entry, joseph wright ‘of derby’ 1734–1797 ng 725 an experiment on a bird in the air pump.

Judy Egerton , 2000

Extracted from: Judy Egerton, The British Paintings (London: National Gallery Company and Yale University Press, 2000).

© The National Gallery, London

Oil on canvas , 183 × 244 cm ( 72 × 96 in .)

Inscribed Jo s . Wright Pinx t 1768 across the centre of the back of the canvas

Purchased from the artist for £200 by Dr Benjamin Bates, 1 by whom given or bequeathed to Walter Tyrrell; Edward Tyrrell, by whom offered (as ‘the property of a gentleman’ ) at Christie’s, 8 July 1854 (163), bt in; presented by Edward Tyrrell to the National Gallery 1863.

SA 1768 (193), and in its special exhibition in September 1768 in honour of the King of Denmark (131); Derby, Corporation Art Gallery, Wright of Derby Bicentenary Exhibition , 1934 (36); Derby Art Gallery and Leicester Art Gallery, Paintings and Drawings by Joseph Wright ARA , 1947 (36); Washington, National Gallery of Art, The Eye of Thomas Jefferson , 1976 (109, with detail repr. pp. 44–5); Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, 1700‐tal: Tanke och form i rokokon , 1979–80 (128, detail p. 18); Tate Gallery; Paris, Grand Palais; and New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Wright of Derby , 1990 (21).

On long loan to Derby Art Gallery 1912–47 , and while there, transferred in 1929 to the Tate Gallery; at the Tate Gallery 1947–71 and 1972–86 (apart from three months November 1982–January 1983, when it returned to the National Gallery in exchange for the loan of NG 6196 and NG 6197 to the Richard Wilson exhibition at the Tate Gallery) .

Richard and Samuel Redgrave, A Century of British Painters , 1866, London 1947 edn, pp. 107–8 ; F.W. Shurlock, ‘The Scientific Pictures of Joseph Wright’ , Science Progress , 1923, pp. 432–8 ; Waterhouse 1953 , p. 192; Eric Robinson, ‘Joseph Wright of Derby: the Philosopher’s Painter’ , Burlington Magazine , c. 1958, p. 214 ; Nicolson 1968 , cat. no. 192, pp. 43–6, 104–5, 112–14, 192, plate 58, with details figs. 47, 49; Werner Busch, Joseph Wright of Derby. Das Experiment mit der Luftpumpe. Eine Heilige Allianz zwischen Wissenschaft und Religion , Frankfurt am Main 1986 , passim ; William Schupbach, Ά Select Iconography of Animal Experiment’, in ed. Nicholas A. Rupke, Vivisection in Historical Perspective , London 1987, pp. 340–7 ; ed. Pierre‐Marc de Biasi, Gustave Flaubert: Carnets du Travail , Paris 1988, p. 350 ; Judy Egerton, Wright of Derby , exh. cat., Tate Gallery 1990, cat. no. 21, plate 21, pp. 58–61 , and see also in this exh. cat. (i) David Fraser, ‘Joseph Wright of Derby and the Lunar Society’ , pp. 19–20, and (ii) Tim Clayton, ‘A Catalogue of the Engraved Works of Wright of Derby’ , cat. no. P2, p. 153, repr.; David H. Solkin, Painting for Money , New Haven and London 1993, pp. 225–39 ; Barbara Maria Stafford, Artful Science , Cambridge, Mass., and London 1994 , pp. 99,102; Christopher Wright, Masters of Candlelight , Landshut 1995, pp. 114–15, detail p. 115 .

Technical Notes

Cleaned in 1974. In good condition, though the darker paint suffers slightly from a fine craquelure which exposes the light ground. Many minor alterations in the composition show through the top layer of the paint, particularly in the figures of the lecturer and his young assistant on the right, where two tassels, or possibly an epaulette, are visible on the shoulder.

Charles‐Amédée‐Philippe van Loo (1719–1795), The Magic Lantern , 1764. Oil on canvas, 88.6 × 88.6 cm. Washington, National Gallery of Art, Gift of Mrs Robert W. Schuette . © 1996 Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington , 1945.10.1.

Detail from An Academy by Lamplight , exhibited 1769 (oil on canvas, 127 × 101.2 cm). New Haven, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection & Fund , B1973.1.66FR .

When the Austrian traveller Count Karl von Zinzendorf visited the Society of Artists exhibition in London in the spring of 1768, he found only one picture worth noting in his journal, 29 April 1768: ‘Il y a un tableau d’une Expérience avec la machine pneumatique, qui se fait de nuit, qui est très beau.’ 2 The reviewer for the Gazetteer on 23 May was even more impressed by Wright’s Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump (193 in the exhibition), writing: ‘Mr Wright, of Derby, is a very great and uncommon genius in a peculiar way. Nothing can be better understood or more freely represented, than the effect of candle‐light diffused through his great picture.’

The exhibition of The Orrery in 1766 and The Air Pump in 1768 marked Wright out as a ‘singular’ (or, in the purest sense of the Gazetteer reviewer’s word, ‘peculiar’ ) artist. These pictures fitted into none of the generally accepted categories of British art. They were too serious to be conversation pieces, and too modern to be history paintings. Their subjects were not sanctioned by literature; nor did they have the slightly saccharine charm of, for instance, Charles‐Amédée‐Philippe van Loo’s The Magic Lantern of 1764 3 ( fig. 1 ). Wright’s Orrery and Air Pump fell, rather, into the category recognised in France as le genre sérieux .

Wright did not invent the idea of ‘candle‐light diffused’ in paintings. Italian, Dutch, Netherlandish and French painters had all produced works in which candlelight, whether its [page 335] source is seen or unseen, throws chiaroscuro effects on faces, gestures, objects and fabrics. 4 Examples within the National Gallery alone include Caravaggio’s The Supper at Emmaus , 1601 (NG 172), Gerrit van Honthorst’s Christ before the High Priest , 1617 (NG 3679), Hendrick ter Brugghen’s The Concert of about 1626 (NG 6483) and Godfried Schalken’s Candlelight Scene: A Man offering a Gold Chain and Coins to a Girl seated on a Bed , of about 1665–70 (NG 999). Nicolson has argued that Wright has strong affinities with the Utrecht School; 5 and so he has, but he can have known only those works which were engraved, 6 or which may by then have been in English collections. Wright did not go abroad until 1773, and did not travel beyond Italy. The ‘candlelight’ painter whose works he is most likely to have seen at first hand is Godfried Schalken (1643–1706), who had spent some years working in England and whose works remained popular with English collectors. 7 Some of them were much copied; Christopher Wright notes that the Boy blowing on a Firebrand (at Althorp probably by about 1700, and now in the National Gallery of Scotland) was copied around 1750 by William Shipley, 8 founder of an art school and (in 1754) of the Society of Arts, whom Wright of Derby would have known.

Detail from An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump (© The National Gallery, London)

But Nicolson also observed that ‘the only contemporary candlelight painter who we can be sure influenced Wright’s genre scenes was Thomas Frye’ (adding that Frye should ‘join the Utrecht School as the chief progenitor of the mode Wright made famous’ ). 9 Thomas Frye (1710–62), 10 portraitist and co‐founder of the Bow porcelain factory, drew and himself engraved in mezzotint two series of large Heads , available in printsellers’ shops in 1760–1, which were startlingly different from the endless engraved portraits of the great, the good and the notorious produced in Britain. Frye’s Heads are not portraits, nor did they carry titles; they are studies in different aspects of contemplation, or stronger emotions such as fear, in the manner of Piazzetta. They inhabit a candlelit world, and what we see of their dress suggests an element of fantasy. Frye’s mezzotint technique dramatised their chiaroscuro effects in a manner which must have appealed powerfully to Wright. Nicolson reproduces several of them: in a telling sequence, he demonstrates Wright’s borrowings from Frye’s so‐called ‘Portrait of a Man seen in profile’ both for the figure of a young draughtsman in An Academy by Lamplight and for the figure of the young boy who peers upwards to watch the experiment in The Air Pump . In homage to Nicolson, and in the knowledge that nothing else would make his point so well, his sequence of illustrations is reproduced here ( figs. 2–4 ( a , b , c ) ).

Thomas Frye ( c. 1710–1762), Man seen in profile looking right, head inclined . Mezzotint, published 1760: image 47.5 × 35.4 cm. London, National Portrait Gallery, D11291. © National Portrait Gallery, London

During the 1760s Wright painted a series of ‘candlelight’ pictures of increasing complexity. The first is probably A Girl reading a Letter by Candlelight, with a Young Man peering over her Shoulder , of about 1760–2. The subject is not new; but Wright’s handling of the effects of light thrown upwards by candlelight on the girl’s face – and, still more interestingly, on [page 336] the more shadowy face of the man behind her – showed an ability to deploy chiaroscuro to dramatic effect which was new in British art. 11 Apart from Thomas Frye, only a few of Wright’s contemporaries showed an interest in such effects. George Romney (1734–1802) painted two small and fairly sketchy ‘candlelights’ in 1761 to include in a lottery exhibition held in Kendal to help finance his move to London, 12 but does not seem to have returned to ‘candlelights’ . Henry Morland ( c. 1719–97) painted (repetitively) slightly coquettish ‘candlelights’ of pretty girls of the lower classes, for which there were Dutch precedents; the first to be exhibited, in 1764, was A Ballad Singer , which interested Horace Walpole sufficiently for him to note ‘singing by the light of a paper candle, in a paper Lanthorn, which she holds in her right hand’ . 13 The almost unknown John Foldsone (fl. 1769–84) exhibited ‘A candlelight’ in 1769; this may have been the subject engraved in 1771 as Female Lucubration (a maidservant with a candle, who may be lighting the way to more than the bookshelf). 14 More interesting than these (but rather later) is Richard Morton Paye’s Self Portrait of the Artist engraving , exhibited in 1783, for whose rediscovery we must thank Alastair Laing. 15

Three Persons viewing the Gladiator by Candle‐light , exhibited 1765. Oil on canvas, 101.6 × 121.9 cm. Private collection. Oxford, Ashmolean Museum (photograph only) Photo © Christie's Images / Bridgeman Images

Wright was essentially a serious‐minded artist. While Morland and Foldsone used candlelight to hint at the availability of pretty girls, Wright sought ways of using candlelight to suggest the very different, studious excitement to be found in the acquisition of knowledge. There is a parallel here with Stubbs, who showed that enamel painting could be used for serious subjects, rather than (as Richard Cosway and others used it) for ‘loose and amorous’ scenes. 16 The first picture which Wright exhibited in London (in 1765, at the Society of Artists) was a ‘candlelight’ : Three Persons viewing the Gladiator by Candle‐light ( fig. 5 ), 17 in which three men study a copy of one of the most famous works of antiquity, the Borghese Gladiator . The mood is studious and reverent. But not all Wright’s candlelights were to be so solemn. Nicolson rightly calls Two Boys fighting over a Bladder ‘the most ferocious picture in Wright’s oeuvre’ , 18 while Two Girls dressing a Kitten by Candlelight depicts ‘play’ of a different kind. 19

In 1766 Wright exhibited A Philosopher giving that Lecture on the Orrery, in which a Lamp is put in place of the Sun ( fig. 6 ). 20 A philosopher (a term then used of a person learned in any science) expounds the movement of the planets round the sun; the beautiful ellipses of the orrery demonstrate it. The audience is made up of seven people of different ages, levels of knowledge and sex. Lectures upon the orrery and other scientific matters became increasingly popular. Sir Richard Steele, writing in 1713, particularly praised the orrery because it ‘administers the Pleasures of Science to anyone’ . 21 The originality in Wright’s painting of the Orrery lies in his perception that a painting on a commanding scale could be made out of a scene which communicates ‘the Pleasures of Science’ to men, women and children of different levels of knowledge.

An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump , exhibited two years later, is larger than The Orrery and, chiefly because of the compelling figure of the lecturer, rather more theatrical. The experiment was by no means new in 1768; what is new is Wright’s ability to make a painting of the impact of the experiment on ordinary people. The air pump itself, an instrument which can create a vacuum in a receiver or container by expelling all the air from it, had been invented over a century before Wright’s picture (by Otto von Guericke, at [page 337] Magdeburg in 1650). Experiments were carried out by scientists all over Europe; among them was Constantijn Huygens, ambassador and ‘philosopher’ , whose portrait by Thomas de Keyser in the National Gallery (NG 212) is justly well‐known, and who, with Nicolas Papin, contributed a paper on the distillation of spirits of the air pump to the Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions in 1675. 22 The air pump was used for various experiments in pneumatic physics, to demonstrate the weight, pressure and elasticity of air. 23 It was first used for animal experiments in 1659, by Robert Boyle and Robert Hooke, who carried out experiments placing larks, sparrows, mice, frogs, kittens etc. in a receiver from which air was pumped out, with varying results (in many cases, death) caused by ‘impeded respiration’ . By the time Wright painted his picture, the air pump had become ‘a common item in cabinets which included instruments of experimental philosophy’ . 24 William Constable of Burton Constable in Yorkshire bought his (a ‘neat double barrell Air Pump with all ye usual apparatus’ ) from the instrument maker Benjamin Cole, Fleet Street, for £21 in 1757. 25 By the 1760s, engravings of scientific equipment had been published in dictionaries and encyclopaedias, with tiny figures or letters keyed to learned exposition. But the public at large probably encountered ‘science’ only in the form of demonstrations by travelling lecturers, 26 usually in town halls, but sometimes, as both The Orrery and The Air Pump suggest, privately, and by invitation.

One of the most solidly professional of the travelling lecturers was James Ferguson FRS, the London‐based maker of astronomical and other scientific instruments, who had lectured on ‘Popular Astronomy’ in London and the provinces since 1749. 27 In about 1760 he decided that he would do better financially to extend the range of his lectures and to organise them into courses, inviting subscribers at one guinea each per course; minimum audience not less than twenty in London, not less than thirty within ten miles of London, and not less than sixty subscribers within a hundred miles of London. 28 The courses consisted of twelve lectures on ‘the most interesting parts of Mechanics, Hydrostatics, Hydraulics, Pneumatics, Electricity and Astronomy’ . 29 Ferguson travelled (presumably by wagon) with his own apparatus – at least fifty different pieces, including an air pump, an armillary sphere, an orrery and much other equipment. He gave his courses in various provincial towns – Bath, Liverpool, Newcastle among them. In 1762, on a Midlands tour, he gave them in Derby. 30

A Philosopher giving that Lecture on the Orrery, in which a Lamp is put in place of the Sun , exhibited 1766. Oil on canvas, 147.3 × 203.2 cm. Derby Art Gallery. Derby Museums and Art Gallery © Derby Museums / Bridgeman Images

Charles‐Nicolas Cochin (1715–1790), Expériences d'électricité (?electrotherapy), ?1760s. Engraving, 6.1 × 10.9 cm. © The National Gallery, London

Whether Wright attended them is not known; the lectures were fairly elementary, and he had enough scientific friends among members of the Lunar Society 31 to have become familiar with ‘apparatus’ such as the orrery and the air pump and their workings. Far more novel in the 1760s were demonstrations with electricity, such as Charles‐Nicolas Cochin depicts in Expériences d’électricité ( fig. 7 ). But Wright’s purpose in painting The Air Pump was not to depict a novel experiment, but to celebrate a new appetite for learning. If he attended Ferguson’s lectures, he is likely to have been as interested in the reactions of the audience as in the content of the lectures.

The air pump was the focal point of any lecture on pneumatics. The lecturer often began by taking a pair of Magdeburg hemispheres – in Wright’s Air Pump , these are the two small linked objects lying on the table near the glass phial of murky liquid – and demonstrating that if the air between them is completely pumped out they become inseparable. Experiments with liquids might follow. But the culminating point was always a demonstration of the potentially lethal effects of depriving living creatures of air. It was possible to demonstrate this in either of two ways: by simulation, placing in the glass receiver a bladder or ‘lungs‐glass’ which could be seen to inflate with air or collapse without it, thereby feigning death; or by placing within the receiver a living creature which would sustain life (increasingly painfully) so long as some air was left in the receiver for it to breathe; the lecturer then enjoyed the god‐like power of either expelling air completely and thus killing the creature, or quickly admitting air and thus reviving it. Lecturers being what they are, most chose the more sensational demonstration on a living creature. Schupbach quotes a dialogue from Benjamin Martin’s The Young Gentleman and Lady’s Philosophy , 1755 ; 32 alas, extracts only can be given here. The young gentleman, dignified by the name of Cleonicus, is bent on demonstrating the air pump to his young and tender‐hearted sister Euphrosyne. Euphrosyne. See here comes John , with a lovely, young Rabbit. I hope that tender Creature is not to be sacrificed for my Sake. – Cleonicus. You are like all the Rest of your Sex. – You think it Cruelty to attempt the Life of a large Animal, but are quite regardless of the Destruction of those which expire under your Feet in every walk of Pleasure you take. – …But to mitigate your Concern, I shall only show, in this Experiment, that the poor Creature does really depend upon the Air for Life; and after that, I shall put it into your Hands, as well as you see it now. – Here, John, put the Rabbit under the Glass. – And now, my good Euphrosyne, have a good Heart, and look on; for turning away your Face will boot the Animal nothing. – See, upon exhausting [the receiver], how uneasy it appears. – As the air is more rarefied, the Animal is rendered more thoughtful of its unlucky Situation, and seeks in vain to extricate himself. – He leaps and jumps about. – A Vertigo seizes his brain. – He falls, and is just upon expiring. – But I turn the Ventpiece, and let in the Air by Degrees. – You see him begin to heave, and pant. – At length he rouzes up, opens his Eyes, and wildly stares about him. – I take off the receiver, and shall now deliver it as recovered from the Dead. Euphrosyne. Poor innocent creature! … Thou shalt always be my darling Rabbit, as by thee, I have been obliged to learn how necessary the Air is for animal Life, and Respiration.

Unlike Cleonicus, Ferguson believed that to experiment with a living creature in the air pump container ‘is too shocking to every spectator who has the least degree of humanity’ . 33 He preferred to simulate death by using the bladder or lungs‐ [page 339] glass, and almost certainly would have done so when lecturing on pneumatics in Derby. Ferguson no doubt gave a thoroughly sound lecture; but his use of a bladder to simulate a life at risk could hardly have inspired the high pictorial drama of Wright’s picture.

Wright’s choice of a ‘living creature’ as the subject of his Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump is likely to have been at least partly inspired by the following lines in The Wanderer , a long poem by Richard Savage: So in some Engine, that denies a Vent, If unrespiring is some Creature pent, It sickens, droops, and pants, and gasps for Breath, Sad o’er the Sight swim shad’wy Mists of Death; If then kind Air pours pow’rful in again, New Heats, new Pulses quicken ev’ry Vein, From the clear’d, lifted, life‐rekindled Eye, Dispers’d, the dark and dampy Vapours fly. Richard Savage (d. 1743), 34 Dr Johnson’s early friend, had himself been reprieved from sentence of death; tried for murdering a stranger in a tavern, he was convicted and taken to the condemned cells at Newgate, but received a royal pardon. The Wanderer was first published in 1729, the year following his reprieve. 35 At some point he must, surely, have witnessed an experiment on ‘some Creature’ in an air pump, whose survival of the ordeal inspired his image of ‘life‐rekindled’ . Wright had a taste for literature, encouraged by his friend and patron, the poet William Hayley; he took several of his subjects from near‐contemporary verse, 36 as well as from Shakespeare and Milton.

In Wright’s first rough sketch for a picture of The Air Pump ( fig. 8 ), 37 the apparatus itself is at the side of the picture; the lecturer is a patient, unassertive figure and the bird he has placed in the receiver is a fairly inconspicuous common or garden songbird – a lark or a thrush – such as was normally used in this experiment. His big picture is altogether more dramatic. On the table, we see the rim of a brass candlestick. The candle it holds is the only source of light in this picture; but it is concealed from us by a large rounded glass, within which (as Schupbach noted) there appears to be a carious [page 340] human skull. 38 As Schupbach observes, ‘Skull and candle are traditional companions in iconography, the candle demonstrating the consuming passage of time, the skull its effect’ ; as emblems of mortality, they remind us that death is inevitable, and imply that the bird will die if deprived of air. 39 If this is what Wright intended, he has strangely underplayed the role of the skull, perhaps because he does not wish to distract attention from his central image. Instead of the usual hollow‐eyed, nose‐destroyed, starkly recognisable skull of traditional vanitas paintings, he shows only part of a carious (diseased) skull, seen from behind, and lacking the mandible or lower jaw. 40 His chief reason for placing it in the glass beaker may have been to add to the concealment of the candle behind it. It remained unrecognised as a skull for two centuries before Schupbach identified it.

First idea for An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump , painted on the verso of Wright’s Self Portrait of c. 1767–8. Oil on canvas, 62.2 × 76.2 cm. Private collection. Image © Omnia Art Ltd

The experiment Wright depicts is evidently taking place in a private house. Probably the man next to the lecturer, pointing upwards, is the host: but who is who hardly matters compared with the fact that the audience is made up of both sexes and of people of widely differing ages. A long tradition identifies the couple on the left as Thomas Coltman and Mary Barlow, both then living in Derby and both friends of the artist; they were to marry in 1769, and sit to Wright for the double portrait Mr and Mrs Coltman (NG 6496, pp. 344–9). Flaubert saw them as lovers. He saw the Air Pump when he was in London in 1865–6, noting in his journal: ‘Wright: Expérience de la machine pneumatique. Effet de nuit. Deux amoureux dans un coin, charmants. Le vieux (à longs cheveux) qui montre l’oiseau sous le verre. Petite fille qui pleure. Charmant de naïveté et de profondeur.’ The spectators range in age from the two little girls on the right – the elder a pure ‘Euphrosyne’ , whose (?) father may well be saying to her ‘Have a good Heart, and look on; for turning away your Face will boot the Animal nothing’ . The oldest is the man seated on the right, not watching the experiment but seemingly sunk in thought. This figure is closely derived, as Michael Wynne has shown, 41 from a pastel drawing by Frye of An Old Man leaning on a Staff , of about 1760; but Wright has lowered the man’s head, so that his gaze seems to centre on the candle and the skull, as if brooding on their implications.

The most detached spectator is the man partly turned away from us, holding a stop‐watch with which to time the convulsions of the ‘subject’ . The only person present who watches the experiment with genuine curiosity is the boy next to him, leaning forwards, and, as Kate Atkinson recently observed, ‘craning his neck to see better, utterly absorbed by his observation’ (see fig. 3 ). 42

Within the glass receiver, Wright depicts a white cockatoo, a rare bird in the Midlands in the 1760s, and one whose life would never in reality have been risked in an experiment such as this: 43 but Wright had already painted a white cockatoo in his portrait of Mr and Mrs William Chase , 44 and knew that its white plumage was just what he needed to show to dramatic advantage in the shadows of this room. As for the lecturer, Wright has transformed him into a magus with a sense of theatre, and placed him so that candlelight heightens the effect of every furrow of his brow and every curl of his silver locks. Busch 1986 sees precedents in an early Netherlandish type of painting of the Holy Trinity – where God the Father points upwards towards the dove of the Holy Spirit, while Christ extends a hand towards the people – in Wright’s central group of the lecturer, the bird and the man pointing upwards. 45

The lecturer’s magnetic expression illustrates only the most obvious of the effects which Wright achieved in this, the most ambitious of all his ‘candlelights’ . Illumined faces seen in close‐up, angled necks such as Mary Barlow’s in her softly dark, sinuously stranded jet necklace, profiles such as the young boy’s half‐hidden in shadow, these are only part of those effects. Just as interesting to Wright is what happens to colours as they recede from light. The lecturer’s showy robe – flashier than any other demonstrator wears in his scenes – can be seen immediately above the light to be of light red damask, woven with arabesques; as the eye travels upwards, further from the light, the stuff darkens to magenta. This observation of changes in colour as light recedes continues throughout the picture. One other example may be given: the young ‘Euphrosyne’ who averts her eyes from the experiment wears, like her sister, a dress of palest lilac. In the light of the candle, these dresses are pale indeed; but as the elder girl turns away from the experiment, her dress deepens from lilac to purple, and finally to black. This, perhaps, is what the Gazetteer meant when praising the effects of light ‘diffused throughout his great picture’ .

Wright depicts the moment when much of the air has already been pumped out of the glass container, by means of the handle attached to the barrels encasing pistons. The bird gasps, and sinks to the bottom of the cage; but it is not yet lifeless. The lecturer’s left hand is poised on the stop‐cock at the top of the receiver; if he turns it in time, the bird will revive; if not, it will die. The lecturer seems to stare out at us as if he had god‐like power of determining life or death; but he will almost certainly have conducted this experiment before, may wish to be invited again (for a fee), knows that actual death distresses a family group like this, and is probably counting under his breath each second of risk he can take before reviving the bird.

Wright’s painting leaves us uncertain of the outcome. A boy by the window holds the cords of a birdcage, waiting for his cue; is he to lower the cage to receive the revived bird, or haul it out of sight because the bird is dead? We cannot be certain: but it should be noted that when Valentine Green engraved his mezzotint of the subject, he indicated – with a few strokes of the graver, and presumably with Wright’s sanction – a just perceptible return of air into the receiver.

Much of the power of Wright’s painting was retained in the mezzotint engraved by Valentine Green. As Tim Clayton 1990 notes, this was based on Green’s own faithful drawing, presumably made soon after the painting’s completion. The mezzotint was exhibited at the Society of Artists in 1769 [page [341]] [page 342] (271); the plate was promptly purchased by John Boydell, who published it for sale at fifteen shillings. Good impressions were in demand, both in Britain and on the Continent. Increasingly weak impressions continued to be printed throughout the nineteenth century. 46

An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump , detail (© The National Gallery, London)

In the Paris Salon of 1771, Charles‐Amédée‐Philippe van Loo (1719–95) exhibited Une Expérience physique d’un oiseau privé d’air à la machine pneumatique , 47 but this has little in common with Wright’s picture; the figures are dressed in the style of the previous century, suggesting that this was in effect a history painting, depicting the air pump while it was still a recent invention, and the vaguely aristocratic characters register distinct ennui: Diderot commented ‘Expérience où aucun des spectateurs n’est à ce qu’il fait.’ 48 A decade later, probably in the early 1780s, Amédée van Loo returned to the subject, but this time very differently. He painted his own family gathered together to watch an experiment with the air pump ( fig. 10 ), 49 with himself in the role of lecturer, Mme van Loo rather nervously clutching a pet dog (but she need not be so apprehensive, for there seems already to be some small creature in the receiver), a boy cranking the apparatus and various members of the family looking on, mostly rather urbanely. It seems likely that Amédée van Loo had seen the mezzotint after Wright’s Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump , and that he adapted Wright’s idea of integrating the subject into a domestic setting.

Wright’s own image of the bird imprisoned in the glass receiver may in a sense have haunted his thoughts. After the gravely beautiful An Academy by Lamplight , exhibited the following year, 50 he painted no more ‘candlelights’ , instead painting a series of ‘night pieces’ , 1771–3, foreshadowed by the glimpse of a full moon riding above clouds in The Air Pump . But at the same time, he was preoccupied with subjects of captives and prisoners. He showed A Captive King (now lost) at the Society of Artists in 1773. 51 Then he painted The Captive, from Sterne’s Sentimental Journey , completing one version in Rome in 1774 and another which was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1778; 52 he also painted several small prison scenes. These pictures were largely inspired by Sterne’s ‘picture’ of a man confined in a dungeon; but it may be recalled that the key passage in Sterne describes Yorick having lost his passport in Paris, joking to himself about being ‘clapp’d up into the Bastile’ . Then he walks into the street, where he hears ‘a voice which I took to be of a child, which complained “it could not get out” ’ . He saw it was ‘a starling hung in a little cage – “I can’t get out” – “I can’t get out” , said the starling’ . Thereafter Yorick could think of nothing but ‘the miseries of confinement’ .

Charles‐Amédée‐Philippe van Loo (1719–1795), Self Portrait as Philosopher, performing an Experiment with the Air Pump before his Wife and Family , c. 1780. Oil on canvas. Archangel’skoe Museum. Archangel’skoe Museum, Russia © The National Gallery, London

1. See Wright’s Account Book (coll. Derby Art Gallery): the picture is twice listed, under ‘Candlelight pictures’ , p. 35, as ‘The Air Pump – 210’ and again, under the same heading but now paid for, as ‘The Air Pump Pd 200’ ; elsewhere in the Account Book is a note that Dr Bates paid for it in instalments. Dr Benjamin Bates, physician, of Little Missenden, Bucks, and friend of Dr Erasmus Darwin, had already bought Wright’s Three Persons viewing the Gladiator in 1765, for £40 (he also bought Wright’s ‘Galen’ , a picture about which nothing is now known: see Nicolson 1968 , p. 236). Bates was also the patron of John Hamilton Mortimer and Thomas Jones, see John Sunderland, ‘John Hamilton Mortimer: His Life and Works’ , Walpole Society 1986 , vol. LII, 1988, under cat. no. 85: The Progress of Vice , four paintings of 1774 painted for Dr Bates, of which two survive; and ed. A.P. Oppé, ‘Memoirs of Thomas Jones’ , Walpole Society 1946–48 , XXXII, 1951, pp. 33–5, 38 . ( Back to text .)

2. Quoted by Robinson 1958 , p. 214. ( Back to text .)

3. Coll. NGA , Washington (880), with a companion picture, Soap Bubbles (881). ( Back to text .)

4. See in particular Benedict Nicolson, ‘Artificial Light in Painting in the 17th Century’ , text of a lecture given in the 1970s, published in ed. L. Vertova, Caravaggism in Europe , Turin 1979 , vol. I, pp. 258. See also Wright 1995 , passim , including 75 ills, in colour. ( Back to text .)

5. Nicolson 1968 , pp. 39–40; and see p. 47: ‘When we come to discuss Wright’s genre scenes, it will be to Honthorst and Terbrugghen to whom we shall most often refer.’ ( Back to text .)

6. The Caravaggio Supper at Emmaus was engraved by Pierre Fatoure in 1629. The Honthorst (NG 3679) was engraved by Pietro Fontana (1762–1837), i.e. too late to have influenced Wright’s candlelights. No engraving of the Schalken (NG 999) is recorded in MacLaren/Brown 1991. ( Back to text .)

7. See Andrew W. Moore, Dutch and Flemish Painting in Norfolk , exh. cat., Norfolk Museums Service 1988 , p. 8, noting particularly two versions of Schalken’s Boy blowing on a Firebrand ( ‘The Boy blowing the Coal’ ) in English collections by the mid-eighteenth century: ( 1 i ) recorded at Althorp, in 1746 ( Kenneth Garlick, ‘A Catalogue of Pictures at Althorp’ , Walpole Society 1974–1976 , XLV, 1976, p. 76 , cat. no. 585): now coll. NGS ; (ii) in the collection of Henry Bell at King’s Lynn. Moore also notes (p. 26) three small candlelights by Schalken in the collection of the dealer and collector Matthew Boulter of Yarmouth by 1778. ( Back to text .)

8. Wright 1995 , p. 133, under no. 68. ( Back to text .)

9. Nicolson 1968 , p. 48. For his discussion of Frye as an influence on Wright, see pp. 42–4, 46, 48–9. ( Back to text .)

10. See Michael Wynne, ‘Thomas Frye (1710–1762)’ , Burlington Magazine , CXIV, 1972, pp. 79–84 , figs. 13–31. ( Back to text .)

11. See A Girl reading a Letter by Candlelight, with a Young Man peering over her Shoulder, c. 1760–2, coll. Col. R.S. Nelthorpe; Nicolson 1968, cat. no. 207, plate 45; Egerton 1990 , cat. no. 14, repr. in colour. See also A Girl reading a Letter, with an Old Man reading over her Shoulder , ? exh. SA 1767 or 1768 : Nicolson 1968 , cat. no. 205, plate 77: Egerton 1990 , cat. no. 15, repr. in colour. ( Back to text .)

12. See Mary Bennett, ‘Boy with a Candle’ , Burlington Magazine , CXIX, 1977, p. 857 . Another picture by Romney of a boy (probably also his brother James) with a candle was formerly with Sidney Sabin. ( Back to text .)

13. Exh. SA 1764 (73). Walpole’s catalogue annotation is quoted by Graves 1907 , p. 175. There are many versions, including one in the Tate Gallery (N 05471), whose collection also includes A Lady’s Maid soaping Linen and A Laundry Maid Ironing . ( Back to text .)

14. For Foldsone, see Waterhouse 1981, p. 128. ( Back to text .)

15. Coll. National Trust (Upton House): exh. SA 1783 (203). See Laing 1995 , p. 70, repr. p. 71 in colour. ( Back to text .)

16. Ozias Humphry, MS ‘Particulars of the Life of Mr Stubbs’ , coll. Liverpool City Libraries . ( Back to text .)

17. Exh. SA 1765 (163). Private collection; Nicolson 1968 , cat. no. 188, plate 52; Egerton 1990 , cat. no. 22, repr. in colour. ( Back to text .)

18. Nicolson 1968 , p. 50. Private collection; Nicolson 1968 , cat , . no. 206, plate 76; Egerton 1990 , cat. no. 16, repr. in colour. ( Back to text .)

19. Coll. Iveagh Bequest, Kenwood House, London; Nicolson 1968 , cat. no. 212, plate 75; Egerton 1990 , cat. no. 17, repr. in colour. This subject is derived from an engraving by Charles‐Nicolas Cochin of 1740. ( Back to text .)

20. Coll. Derby Art Gallery; Nicolson 1968 , cat. no. 190, plate 54, with details figs. 37–8; Egerton 1990 , cat. no. 18, repr. in colour; and see David Fraser in Egerton 1990 , pp. 16–17. ( Back to text .)

21. Quoted by Francis Maddison, ‘An Eighteenth Century Orrery by Thomas Heath and some earlier orreries’ , Connoisseur , CXLI, 1958, pp. 163–4 . ( Back to text .)

22. Published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, Abridged , vol. II, 1672–83, London 1809, pp. 239–40 . ( Back to text .)

23. See Schupbach 1987, p. 341. ( Back to text .)

24. Schupbach 1987, p. 341. ( Back to text .)

25. See William Constable as Patron 1721–1791 , exh. cat., Ferens Art Gallery, Kingston‐upon‐Hull 1970 ; both the air pump supplied by Cole and his receipt for William Constable’s payment were exhibited (cat. nos. 128–9). ( Back to text .)

26. Among these, Schupbach 1987 lists John Theophilus Desaguliers (1683–1744), Benjamin Worster ( fl. 1719–30), Benjamin Martin (1704/5–76) and Adam Walker (?1731–1821), as well as James Ferguson (1710–76). ( Back to text .)

27. See E. Henderson, Life of James Ferguson, F.R.S., Edinburgh, London and Glasgow 1867 , p. 133. See also John R. Millburn, Wheelwright of the Heavens: The Life and Work of James Ferguson, F.R.S., London 1988 . ( Back to text .)

28. Ferguson, Tracts and Tables , first published 1767 , with lists of apparatus to be used in the lectures, in Henderson 1867 , pp. 343–8. ( Back to text .)

29. This is the syllabus as published in 1769; see Henderson 1867 , p. 355. ( Back to text .)

30. Henderson 1867 , p. 268. Henderson records that in the Midlands Ferguson gave ‘his usual course of lectures on Astronomy, Mechanics, Hydraulcs. &c .’ ; but almost certainly it would have included the customary lecture on pneumatics (including the air pump). Ferguson repeated his course of lectures in Derby in 1771. ( Back to text .)

31. For the Lunar Society, established in Birmingham around 1764–5, see Robert F. Scholfield E. Schofield , The Lunar Society of Birmingham , Oxford 1963 ; a short account is given by Fraser (in Egerton 1990 ), p. 15. Its members were Midlands scientists, manufacturers, doctors, etc. Wright was not himself a member of the Lunar Society; his closest contacts with that Society were through his friend and near neighbour in Derby, John Whitehurst FRS (1713–88), maker of clocks, barometers and other instruments, and Dr Erasmus Darwin, who moved from Lichfield to Derby in 1783. For Wright’s portraits of Darwin and Whitehurst, see Egerton 1990, cat. nos. 144–5, 147. ( Back to text .)

32. Quoted by Schupbach 1987, pp. 342–3, from Martin 1755 , vol. I, pp. 398–9. ( Back to text .)

33. James Ferguson, Lectures on Select Subjects , London 1760 , p. 200; quoted by Nicolson 1968 , p. 114. ( Back to text .)

34. For Richard Savage, see Richard Holmes, Dr Johnson and Mr Savage , London 1993 , passim . The quotation is taken from ed. Clarence Tracy, The Poetical Works of Richard Savage , Cambridge 1962 , p. 128. ( Back to text .)

35. See ed. Tracy 1962 , pp. 94–5. The Wanderer was begun in 1726–7. In December 1727 Savage was tried for murder, and condemned to death; he was pardoned in January 1728, and completed the greater part of The Wanderer later that year. ( Back to text .)

36. For instance, Edwin, from Dr Beattie’s Minstrel (Nicolson 1968, cat. no. 235); The Dead Soldier (Nicolson 1968, cat. nos 238–40), taken from John Langhorne’s The Country Justice (and various scenes from Sterne). ( Back to text .)

37. Private collection. Painted c. 1767 on the reverse of a Self Portrait , 62.2 × 76.2 cm, turned sideways. Nicolson 1968 , cat. no. 193, plate 59. ( Back to text .)

38. Schupbach 1987, p. 346. ( Back to text .)

39. Schupbach 1987, p. 346. ( Back to text .)

40. In correspondence with the compiler 1988–90, Schupbach observes that the skull is lacking part of the jaw. ( Back to text .)

41. See Michael Wynne, ‘A Pastel by Thomas Frye’ , British Museum Yearbook II: Collectors and Collections , London 1977, pp. 242–4 , fig. 204; also repr. Egerton 1990 , p. 61, fig. 10. The drawing appears to have belonged to the Tate family of Liverpool, perhaps to Thomas Moss Tate, Wright’s pupil; thus it was probably easily accessible to Wright. ( Back to text .)

42. Kate Atkinson, ‘Author’s Picture Choice’, in NG News , June 1997 [pp. 1–2] . ( Back to text .)

43. Schupbach 1987, p. 347. ( Back to text .)

44. Private collection, New York; c. 1762–3, Egerton 1990 , cat. no. 13, repr. in colour. ( Back to text .)

45. Busch 1986 , pp. 26–49. ( Back to text .)

46. See Clayton 1990 , p. 235. ( Back to text .)

47. Repr. Diderot: Salons , ed. Jean Seznec, Oxford 1967 , vol. IV, fig. 81, as ‘ancienne collection Youssoupoff’ (USSR). The compiler is indebted to her colleague Humphrey Wine for drawing this picture to her attention. ( Back to text .)

48. Diderot: Salons , p. 175. ( Back to text .)

49. The painting is reproduced here from a reproduction in Charles Oulmont, ‘Amédée van Loo’ , Gazette des Beaux‐Arts , 1912 , 2 parts, Pt ii, p. 149. ( Back to text .)

50. Coll. Yale Center for British Art; exh. SA 1769 (197), Nicolson 1968 , cat. no. 189, plate 60; Egerton 1990 , cat. no. 23, repr. in colour. ( Back to text .)

51. Exh. SA 1773 (370). Walpole thought the figure ‘bad and inexpressive’ , and noted that he had ‘a lanthorn hanging over him’ . Nicolson 1968 (cat. no. 214, as untraced) thinks this captive was probably the crusader Guy de Luignan. ( Back to text .)

52. The Captive , 1774, is coll. Vancouver Art Gallery; Egerton 1990 , cat. no. 53, repr. in colour. The Captive , exh. RA 1778 (360), is coll. Derby Art Gallery ( Nicolson 1968 , cat. no. 217, plate 162). ( Back to text .)

Abbreviations

List of archive references cited.

- Liverpool , Liverpool City Libraries, Picton Collection : Ozias Humphry , Particulars of the Life of Mr Stubbs… given to the author … by himself and committed from his own relation , MS, c.1790–7

List of references cited

List of exhibitions cited, arrangement of the catalogue.

This is a catalogue of the 61 works which represent the British School in the National Gallery now, at the beginning of 1998. The first Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the National Gallery, with Critical Remarks on their Merits , by W. Young Ottley, was published in 1832 (earlier catalogues were hardly more than hand‐lists). The first scholarly catalogue devoted to the Gallery’s British pictures – National Gallery Catalogues: The British School – was compiled by Martin Davies (Director 1968–73). Its first edition in 1946 included 333 pictures. By 1959 , when Davies published a revised edition (following large transfers of pictures upon the Tate’s separation in 1954 from the National Gallery in 1954), the number of British pictures in the National Gallery had been reduced to 99.

Martin Davies’s British School catalogue still stands as a model of concise record and meticulous (sometimes astringent) footnotes. This catalogue is chattier. I have tried to combine accurate information about the making and subsequent history of the pictures with more concern for their subject matter than Martin Davies allowed himself. Here I share to the full Neil MacGregor’s conviction that the public should have as much information as possible about their pictures. In a collection still dominated by portraits, much information about sitters (men, women and, in the largest portrait of all, a horse) is available; some of it may help to assess how far a portraitist has succeeded in reflecting [page 17] individual character. The background information offered here can, of course, be skipped, leaving the illustrations – or better still, the actual works – to speak for themselves.

All the works have been examined in the company of Martin Wyld, the Gallery’s Chief Restorer. He has compiled all the Technical Notes except for those on Hogarth’s Marriage A‐la‐Mode , which have been contributed by David Bomford. Many of these Technical Notes incorporate the results of detailed examination by Ashok Roy, Head of the Scientific Department, and by his colleagues Raymond White and Jennie Pilc. The bibliography of published work on the techniques and pigments used by artists during the period covered by this catalogue ( pp. 432–5 ) has been compiled by Jo Kirby of the Gallery’s Scientific Department.

The catalogue is arranged in the two parts into which it fairly naturally falls. Part I catalogues the well‐known and deservedly popular works which are nearly always on view (except when lent to outside exhibitions). The artists represented in it are Constable, Gainsborough, Hogarth, Thomas Jones, Lawrence, Reynolds, Sargent, Stubbs, Turner, Wilson, Wright of Derby and Zoffany, arranged in alphabetical order, with their works (when more than one) in their known (or likely) chronological sequence. The time‐span of works by this small group of twelve artists is hardly more than 150 years, from Hogarth’s six paintings of Marriage A‐la‐Mode , of about 1742, to Sargent’s Lord Ribblesdale , dated 1902. In this part of the catalogue, movements of pictures to and from the Tate are briefly noted (below the heading Exhibited), such information being offered to reassure those who remember seeing, say, Wright of Derby’s An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump in the Tate rather than in the National Gallery (or recalling locations given in past literature) that their recollection was not at fault. Under this heading, movements for short periods usually indicate loans supplied by the Tate to fill gaps on the National Gallery walls when it lent pictures for exhibition elsewhere. ‘Tate 1960–1’, frequently noted, indicates the period of the Gallery’s winter exhibition National Gallery Acquisitions 1953–62 ; to make room for this exhibition, most of its British School pictures were accommodated and displayed in the Tate Gallery.

Part II catalogues the Gallery’s collection of portraits (including four marble busts) of those who played significant parts in the history of the National Gallery itself. Since it is in a sense a narrative (though an incomplete one) of the Gallery’s history, Part II is presented chronologically, according to the various sitters’ relationships to the National Gallery. Lawrence is the only artist to appear in both parts of this catalogue (his portrait of * Queen Charlotte appears in Part I , his two portraits of * John Julius Angerstein in Part II ). In this group, Sir George Beaumont (grudgingly sitting to Hoppner, an artist he habitually denigrated) will be a familiar figure in the history of British art. Other Trustees and benefactors – preeminently, perhaps, Layard of Nineveh – will be better known outside the perspectives of the National Gallery, while two of its minor heroes – William Seguier, the Gallery’s first Keeper, and William Boxall RA , its second Director – may hardly be known at all.

Few portraits of National Gallery benefactors were ever transferred to the Tate; the only exceptions appear to be the transfer of the first version of Linnell’s portrait of Samuel Rogers (the National Gallery retaining a second version) and the transfer in 1949 of Hoppner’s portrait of Charles Long, Lord Farnborough , accepted by the National Gallery as a gift in 1934, but hung for a few months only, before being pronounced by Sir Kenneth Clark (Director, 1933–45) ‘not worth a place’. The National Gallery retains a finer image of Long in the form of Chantrey’s marble bust. Most of the works in Part II are hung in the Reception Area or the Reserve Collection.

All but one of the benefactors who figure in Part II have one thing in common: they bought pictures, but begat no heirs, and therefore chose to give or bequeath paintings to the National Gallery. The exception is the actor‐manager Thomas Denison Lewis, who in 1849 bequeathed not only * Mr Lewis as The Marquis in the Midnight Hour (Shee’s portrait of his famous actor‐father), but also £10,000 for future Gallery purchases. Prudently invested, the Lewis Fund enabled the purchase of many National Gallery pictures of all schools, including two much‐loved British pictures: the Heads of Six of Hogarth’s Servants and Gainsborough’s * Cornard Wood . The Hogarth was transferred to the Tate in 1960: thus, unknowingly, Lewis became a benefactor to both institutions.

Ann An Appendix includes provisional catalogue entries for * Portrait of a Lady , painted by Cornelius Johnson (or Jonson van Ceulen) after his return to Holland, and * On the Delaware , by the wholly American painter George Inness. Both were included in Martin Davies’s British School catalogue, but since they do not properly belong to the British School, they will eventually be included in more appropriate Schools catalogues.

About this version

Version 1, generated from files JE_2000__16.xml dated 14/10/2024 and database__16.xml dated 16/10/2024 using stylesheet 16_teiToHtml_externalDb.xsl dated 14/10/2024. Structural mark-up applied to skeleton document in full; entry for NG524, biography for Turner and associated front and back matter (marked up in pilot project) reintegrated into main document; document updated to use external database of archival and bibliographic references; entries for NG1207, NG130, NG925, NG6301, NG1811, NG6209, NG113-NG118, NG1162, NG6544, NG4257, NG681, NG3044, NG6569, NG538, NG6196-NG6197 and NG725 proofread and prepared for publication; entries for NG113-NG118, NG1207, NG1811, NG4257, NG524, NG538, NG6209, NG6301, NG6569 and NG725 proofread following mark-up and corrected.

Cite this entry

Our App! Android

Joseph Wright of Derby - The experiment with a bird in the air pump

by Alexandra Tuschka

Here we are immediately caught up in a real spectacle: kindly, the other people have left us a place to catch a good view of the experiment, which has already reached its climax. Brightly illuminated by a candle standing behind a glass bulb, we first have to classify what we are about to see. Already our eye is caught by the poor little bird - a crested cockatoo - which is struggling for its life here. The air pump extracts oxygen from the large glass container.

The construct goes back to the inventor Robert Boyle, who developed this experiment in the 1660s. At the time the work was created, it was already about 100 years old. Nevertheless, it has lost none of its fascination, here it is literally staged, on the one hand by the painter, on the other hand by the scientist on the canvas.

Those present react quite differently to what is shown. On the far left, a young pair of lovers has eyes only for each other. Their faces, defined by the strong chiascouro, turn lovingly to each other. They have taken advantage of the evening spectacle to secretly get closer to each other. The dim light makes the scene almost romantic. Two more people on the left front have their backs turned to us. A boy leans forward and wants to watch everything closely. He has no sympathy, but is filled with great interest in the experiment. In front of him sits a man with a stopwatch. There is no expression on his face. In the center, our gaze falls on the experiment director. He has flowing, gray hair, a narrow face and looks at us. With one hand, he points questioningly at us, the other will or will not open the valve. It is as if he is asking us whether the bird should live or die. With his red coat in the gloomy scene, he also reminds us of a magician. The strong chiaroscuro makes his appearance all the more drastic. Like a spotlight in the theater, we see only the most important things illuminated. What is also magical is that he makes something invisible visible; for the people of the time, the components of air were not yet so well explored and were a great mystery. Furthermore, Wright enhances the tense scene with clever details, such as the reflection of the table or the animal lungs that are in the milky container on it. They all support the successful staging of the man. The two so-called "Magdeburg hemispheres" are also on the table. A simple but impressive experiment on air pressure was probably carried out with them beforehand.

On the right side of the picture, a group of three is brightly illuminated. One could assume that the bird belongs to the two girls, who are probably sisters, the younger of whom cannot decide between looking towards and away, the older already burying her face in her hands. The father tries to explain the experiment to the two children in a matter-of-fact way. Another man can be seen in profile in front on the right. He has lowered his gaze and seems to be pondering. He has even taken off his glasses, which are now in his right hand. Possibly he asks himself the question whether a moral border is crossed here. Is a person allowed to decide about life and death in this way? Where would that lead? Further in the shadow and apart from the group a boy is recognizable, who pulls up or lets down the cage at a rope. Here the viewer is asked to complete the outcome of the scene in his mind's eye. So the decision is literally ours to make and is cleverly held in abeyance by Wright. If we decide to let the bird live, the man instantly turns on the valve, the bird recovers, and the cage is ready. If we decide otherwise, it may be too late and the empty bird cage, now no longer needed, is pulled up by the boy.

The 18th century, the age of enlightenment and scientific revolution, also produced so-called "traveling scientists" or "natural scientists". These demonstrated numerous experiments in the home environment and needed few utensils to do so. We are here in an interior, through the strong chiascouro is not clear where exactly this should be. These strong contrasts are reminiscent of the Utrecht Caravaggists such as Gerrit van Honthorst, who, however, could only have been known to Wright - if at all - through prints.

Here the moon is recognizable as a second source of light, possibly with further significance in terms of content: for Wright had good contacts to the "Lunar society", although he was not a member, he moved in highly educated, elite circles. Among these were Richard Arkwright and the grandfather of Charles Darwin, Edward Darwin. This society often met during the full moon. This may have had practical reasons: for a long time the moon was the only source of light at night and offered a little security on the - possibly late - way home. His closeness to these scientifically interested circles is also evident in many of the painter's other motifs. It was here that Wright achieved great fame. However, since he lived outside London and specialized in these subjects, his influence on other artists was very slight. Thus, his so-called "noctures" or "candlelight" paintings are almost unprecedented in the English artistic landscape.

Joseph Wright of Derby - The Experiment with a Bird and the Air Pump

Oil on canvas, 1768, 183 x 244 cm, National Gallery, London

Experiment to demonstrate the air pressure, Magdeburg hemispheres

Drawing, 1672

Gerrit van Honthorst - The False Players

Oil on canvas, 17th century, 125 x 190 cm, Museum, Wiesbaden, Germany

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema - Phidias showing the Frieze of the Parthenon to his Friends

George Seurat - The circus / At the gallery

Albrecht Dürer - Self-portrait

Your Custom Text Here

What They Don't Tell You About Paintings - Joseph Wright of Derby - Experiment on a Bird in an Air Pump

Joseph Wright of Derby – Experiment on a Bird in an Air Pump - 1768 - National Gallery London - Oil on Canvas.

Wrights and Wrongs

If you read my post on Velazquez’ Bacchus, you might recall that one figure stares cheerfully out at us, while others within the arrangement are more contained. I pointed out how the device draws us into the scene. This got me thinking about similarly constructed works where a single character within a small crowd locks eyes with us to involve us in the group’s experience. Perhaps, I thought, I should have a look at another. This lavish expedition into light, shade and colour was the candidate that sprang to mind more or less instantly. But unlike the Velasquez where we’re asked to join in and drink deep, this piece poses a bit more of a challenge. Let’s have a look.

The Drinks Party Guy

Here’s the chap doing the staring. A bit manic, it has to be said. Big hair, liddy eyes, loose lips, wrinkled brow. There’s something unsettling about this bloke. He has a peculiar vibe. Probably not the guy you want to get cornered by at a standing up social event like a barbecue or drinks party. It doesn’t help that he appears to have arrived at this evening’s get-together in a dressing gown. This is not good. We’re in the territory of the awkward uncle who everyone avoids until he turns up in his underwear on Christmas morning with his cat on a lead and then starts shouting energetically at your granny about Rubik’s cubes and hidden bases on the moon.

But perhaps we shouldn’t leap to judgements. In this painting, the barmy looking eccentric is presenting us with a thorny moral dilemma. He is the invigilator in a loose variant of a Schrödinger’s Cat scenario, where we will make an observation that decides an outcome. I’ll explain this a bit better in due course. But we have a few bits and pieces to cover before we get that far. First we need to understand what exactly we’re looking at and what kind of background context it’s set against.

The painting’s by a chap called Joseph Wright of Derby, a relatively provincial figure in English painting. It was done towards the end of the 1760s and is called ‘An Experiment on a Bird in an Air Pump’. This is the point in time when the Georgian era was in full swing. Britain was booming thanks to the first phase of a burgeoning empire, and – importantly for our purposes - Enlightenment thought and rationalism were very much to the fore. I know this sounds like the beginning of one of those excruciating cross tabulations of art with socio-politics that are cranked out by academics obsessed with social history. But don’t switch off quite yet. It’s not going to be as grim as that. And this one is well worth your time. Just stick with me over the next five or six paragraphs before throwing in the towel.

One of the trends that defined the Enlightenment, as everybody knows, was an explosion in rational inquiry. Interested amateur gentlemen began dissecting the observable world in an effort to understand how everything around us ticked. If they had the means, they passed their days in their studies, attics and outhouses, often made their own equipment, and generally got stuck in. All that nature had to offer was up for analysis. And one of the questions that troubled the Enlightenment’s best minds was whether or not it was possible for a vacuum to exist.

Spheres And Seals

This may sound like a strange question to modern ears. But bear in mind that since antiquity it had been assumed that a vacuum was an impossibility. A void of nothingness in a world of somethingness? Preposterous. A metaphysical impossibility as much as a physical one. And so the thinking went until about one hundred years before our painting was knocked out by Wright. A clever German chap fashioned a pump that could suck air. He had two copper hemispheres built, smeared their rims with grease, pressed them together, and with his pump pulled the air out of the sphere they formed. The proof that he had created a vacuum lay in the fact that anyone could pull the hemispheres apart before he pumped them. But afterwards two teams of horses couldn’t split them. The ‘nothing’ that was within was being pressed upon by the ‘something’ that was outside.

The copper half spheres were called Magdeburg hemispheres, by the way. (I just want to flag this for you because they’ll crop up again later.) Once they had demonstrated that a vacuum could exist, as is often the case in scientific matters, another important question arose. If the hemispheres were held together by the something that was air pressing on a space that contained the nothing that was no air, what on earth was air? Again, we moderns take the answers to fundamentals like this for granted. But it really wasn’t at all clear to our forebears, who were bamboozled by the question, and found themselves scratching their heads at a loss to figure it out.

Bane Of The Chemistry Class

Not much progress had been made when the man in this rather severe portrait took an interest in the question. This is Robert Boyle. You might recall his eponymous law from chemistry class in school. Or perhaps you’re more like me - I was not as diligent as I could have been on that day in Mr. Moloney’s lab. Boyle had a logical insight. Maybe, he reasoned, we could work out an understanding of the nature and properties of air by observing what happens when it is denied to things that are usually surrounded by it. The man was nothing if not thorough. He realised he’d have to assess an extensive sample of these things if his experiments were to have any merit. And inevitably, the list of items destined for his tests included a variety of animal life.

Boyle got together the necessary air pump and some strong glass jars that enabled him to see what was going on inside as a vacuum was created around various species of animal he obtained. I needn’t tell you how this worked out for the little creatures. And to be fair to Boyle, he wasn’t so keen on what happened to them either. He called the death of the first bird he placed in a vacuum ‘a tragedy’. But he was a searcher after truth, no matter where it led. He managed to demonstrate that something about the air around us was of critical life-giving importance for much fauna. This was news. It was also a powerful example of how experiments could vividly reveal things that were previously hidden from us.

Sparked by pioneers like Boyle, a new rational approach to understanding the world took a firm hold over the next hundred years. Observable experimentation was all the rage. In Britain, the public’s appetite for scientific demonstrations involving electricity, vacuums like Boyle’s and so on grew particularly strong. (I ought to be careful here. The word ‘science’ was not in use yet. Not in the sense we understand it. Just bear that in mind, as I’ll be using it again as we go forward in place of the more cumbersome ‘natural philosophy’ I should deploy.) Over time, a sort of travelling ‘natural philosopher’ emerged who would go from place to place to carry out these demonstrations for a paying public. And the wild looking individual I started this story with is one such character.

So now we understand that what we can see in the painting is a natural philosopher recreating a famous experiment. It takes place in the house of a well-to-do Georgian family around a century after Boyle’s original effort. And on first glance all appears pretty much as you would expect it to. There is some understandable emotional drama with the two children, while those others who are present look on at an improving and educational demonstration. But as we do our dive, we’ll discover that there are less obvious tides moving beneath the surface.

Carefully Located

The first thing to note is that this picture is built with light and shade. As is often the case with the best examples of this dramatic style of painting, the majority of the canvas is barely worked at all. Squint hard so the picture blurs for you, and you’ll see what I mean. The normal routine when viewing such a piece is to pay particular attention to those areas which are brightest. These are the zones that the painter wants to stand out and attract our attention. With this in mind, we immediately notice that the brightest element in the picture is the open jar filled with cloudy liquid containing a stick and some unidentifiable looking object. Not only is it the brightest space in the picture, it’s also dead centre on the horizontal plane. Obviously Wright wants us to consider this item carefully. And we will. But not before we have a look at a few other things. For now, I just want to put it on your radar.

There are a couple of other points of light we need to focus on. The first of them is the two children and what we must assume is their father. (Have a look at how beautifully Wright has arranged the girls, by the way - the gestures their hands make, the tilt of their heads, the smaller girl’s solitary two teeth. Magnificent.)The kids aren’t happy. They’re clearly distressed by what’s going on. We can assume from how well lit they are that Wright wants their anguish to come across to us strongly. The source of their upset is also robustly illuminated. The pale bird in the jar fluttering and suffocating in the vacuum. There’s something unusual about that bird.

Preliminaries

In his initial - and surprisingly crude - sketch for the picture, Wright intended to deploy a more run of the mill bird that might be found in any English hedgerow. But in the end, he opted instead for an exotic cockatoo. The greater scale of bright white plumage grabs our attention and suits his design objectives better than, say, a smaller duller thrush would. But what’s curious about this choice is that no travelling philosopher of the time would use such an expensive bird in a fatal experiment. It’s an import. Regularly sourcing and killing cockatoos would have been hopelessly impractical. And probably close to unaffordable. When we look to the top right of the picture, we see it must have come from the open bird cage hanging from above. It appears this cockatoo is a pet. No wonder the girls are upset. This fatal experiment is being performed on a beloved family member. It’s all a bit too close to the bone.

Check It Out, dude

And what’s all this suffering for anyway? If we look around the table, it’s not clear many people are even that interested in what’s going on. If we squint again, it’s apparent that Wright wants us to notice the young couple on the left. They’re ogling each other about as passionately as was publicly permitted by conventional Georgian etiquette. They’re besotted and seem happily unaware of their surroundings. It seems love has no time for scientific demonstrations. (Wright, by the way, would paint them both again a few years later when they married.) The boy seated below them is engrossed, but like a teenager gawping at road-kill. He’s not profiting in a meaningful way from the spectacle. The father across the table is too busy trying to explain things to his broken hearted daughters to pay attention. The older man on the right seems lost in far away thoughts. The young boy in the background is occupied with tasks of his own.

Darwin Senior

Only one person is constructively engaged with what’s taking place. The man in green below the philosopher. He holds in his hand a pocket watch. In the proper Enlightenment spirit, he times the cockatoo’s ordeal. This figure is Erasmus Darwin, a polymath, talented physician and grandfather of Charles. In fact, we know this scene was set in the study of his house. To this day, when it’s at its zenith, the moon is visible in exactly this position through the study window. That moon, you will have noticed, is another one of the highlighted areas. We’ll return to it towards the end of our expedition into the painting.

Paraphernalia

What was Wright trying to establish with this picture? The answer, I think, hinges on what is in the shining glass jar in the centre of the painting along with a number of other items scattered across the table. We’ll start with the sundry smaller objects. It may be hard to discern them clearly in this reproduction but we can find a candle snuffer, an eighteenth century alcohol thermometer, a bottle, straw and cork and finally a miniature pair of the Magdeburg hemispheres we discussed earlier. All of these objects share a common characteristic.

Each of these items can be used to illustrate some of the properties or effects of a vacuum. When the snuffer is placed snugly over a burning candle, the air inside is consumed by the flame until none is left. In the ensuing airless void, the flame winks out. The alcohol thermometer’s liquid levels can rise and fall in response to temperature changes thanks to the vacuum within which the alcohol sits. When the straw in the little bottle is sucked on, a vacuum is created within it. Air pressure on the liquid in the bottle forces it up the straw into that vacuum. When the bottle is empty, if a cork is placed in its neck and the bottle then left in an air pump like the one operated by the philosopher, the differing air pressures inside and outside the bottle will force the cork to pop out. The Magdeburg hemispheres, as we already noted, cannot be separated when joined together and pumped empty due to air pressure surrounding the vacuum within. Vacuums, vacuums, vacuums. So many ways to demonstrate and examine vacuums.

Experimental Lungs

Finally we return to the radiant glass jar I mentioned before. That weird item within it has been much discussed. The majority of art historians who’ve taken a shot at identifying it suggest it is a deteriorated skull, a motif of death to echo the fate of the cockatoo. Having examined the other bits and pieces on the table, that seems unlikely though, doesn’t it? Particularly as there’s an alternative theory that states this is a pair of lungs from a sheep or pig. (It’s thought that some travelling philosophers made use of such organs in their demonstrations, so this would not have been as peculiar as it seems at first to us.) The surrounding liquid perhaps preserves the organ - a pointless precaution if it was a skull. Then there’s that long presumably hollow wand emerging from the lungs in the jar. Blow into it and the organs inflate. Suck on it and they will collapse, mimicking the effect of a vacuum pulling the air out of lungs contained in a chest. In other words, the arrangement in the glowing jar offers the best means possible of illustrating to an audience the effect of an air pump on a living creature. Now we begin to grasp why it’s centre stage in the pictorial design.

The Distant Audience

I think it’s pretty clear Wright is showing us that the demonstration on the cockatoo is unnecessary. Everything that the casual dilettante might want to know about the effects of vacuums on a living being can be easily divined from the other items he’s laid out. The little creature’s agonies are for nothing. They’re worthless. A point reinforced by how utterly uninterested most people around the table are. Take a moment to look at the seated older gent on the right. He seems a thoughtful type of fellow. But he looks down and away from the bird. He’s taken his glasses from their case on the table. But he hasn’t put them on. He simply holds them in his hand. He has no interest in looking that closely. His mind is somewhere else.