Epekto Ng Paggamit Ng Online Class Sa Pag- Aaral Ng Piling Mag-Aaral Sa Unang Taon Sa Medyor Sa Filipino

- Stephanie S. Alba Bestlink College of the Philippines

- Jenalyn C. Arsaga Bestlink College of the Philippines

- Mark Angelo V. Bacatio Bestlink College of the Philippines

- Janeth Ross L. De Vera Bestlink College of the Philippines

- Mhica Shaine O. Mogarte Bestlink College of the Philippines

Ang online class ay umusbong nang magsimulang magkaroon ng pandemya sa ating bansa nga COVID-19 noong taong 2020. Naging daan ang online class upang maipagpatuloy ang pag aaral ng mga mag aaral kahit hindi pumupunta sa paaralan partikular na sa Bestlink College of the Philippines. Ito'y nangangailangan lamang ng mga kagamitan tulad ng kompyuter, o kahit anong gadyet at internet.

Naging malaking hamon ang panibagong paraan ng pag-aaral na ito sa ibat ibang larangan. Anuman ang husay ng mga guro sa kanilang pamamaraan at kagamitang panturo ay hindi pa rin magiging epektibo ang pagkatuto ng mga bata kung wala ang mga magulang na nagmomonitor sa kanilang mga anak sa bahay habang nasa online class ang bata. Mahalagang makipagugnayan ang mga guro sa mga magulang dahil ito ay isa sa mga estratehiya upang maging aktibo ang mga bata sa kanilang pagaaral. Sa pag-aaral na ito'y nalaman ng mga mananaliksik ang epekto ng paggamit ng online class sa mga piling mag-aaral mula sa unang taon sa kolehiyo sa BSED medyor sa Filipino, natukoy at nailahad sa pag-aral na ito kung angkop bang gamitin ang online class sa makabagong panahon bilang ganap na pantulong sa pagtuturo.

Ang isinagawang pananaliksik na ito ay patungkol sa epekto ng paggamit ng Online class sa piling mag-aaral mula sa unang taon sa kolehiyo sa Medyor sa Filipino. Ito ay ginamitan ng deskriptong metodolohiya, pinili ng mga mananaliksik. Ang descriptive survey research design na gumagamit ng talatanungan upang malikom ng mga datos. Ang mga mananaliksik ay naniniwala na ang disenyong ginamit ay ang angkop para sa paksa dahil mas mapapadali ang pangangalap ng mga datos na isinasagawa at naiintindihan ng mga mananaliksik sa pag-aaral na ito ang descriptive survey research design ay nababagay sa pagaaral na isinasagawa kahit limitado lamang ang kanilang respondente. Ito ay dahil hindi lamang sila nakadenpende sa mga sagot sa kanilang talatanungan kundi maaari rin silang magsagawa ng panayam at obserbasyon upang idagdag sa mga nakalap nilang datos at impormasyon. Ang mga mananaliksik ay nangalap ng datos sa paaaralan ng Bestlink College of the Philippines. Ang mga ito ay nagpasagot sa apatnapu (40) na mga mag-aaral sa unang taon ng BSED medyor sa Filipino Panuruang taon 2022-2023. Sila ang aming napiling respondente dahil nais naming malaman kung paano nakaka-apekto sa kanila, Bilang isang mag aaral ang pag gamit ng Online class Mula sa unang taon sa kolehiyo sa Medyor sa Filipino. Makikita sa bahaging ito ang frequency at bahagdan ng bawat respondente ayon sa kanilang edad na 35 o 87.5% ng mga estudayante na kabilang sa edad na 20 na taong gulang, kung saan ito ay mayroong pinakamataas na bahagdan. At mula sa ikalawa pinapakita na ang frequency at bahagdan ng respondente ayon sa kanilang mga kasarian 34 o 85% na babae ang pinakamataas na sumagot sa talatanungan at may pinaka mataas na ranggo. At mula sa ikatlo, Matatagpuan ang frequency at bahagdan ng mga respondente ayon sa kanilang mga 17 o 42.5% ang pinakamataas na nakuha sa paggugol ng oras sa Online class ng mga estudyante sa paggamit ng online learning mode. Dulot ng makabagong paraan ng pag-aaral ito ay nagpapakita sa bawat talahanayan ng weighted mean at bahagdan ng mga respondente ayon sa epektong dulot ng makabagong paraan ng pag-aaral 3.35 ang grand mean nito. At 3.625 ang mean at nakakuha ng pinaka mataas na ranggo. Sa pananaw sa Online class ito ay nagpapakita ng weighted mean ay nakakuha ng mataas na Mean na may 4.45 na lubos na nakaaapekto sa paggamit ng online learning mode, weighted mean at bahagdan ng mga respondente ayon sa ayon sa pananaw ng online class at sa bawat na nararamdaman ng mga estudyante sa iba't-ibang platform extensions for Google Classroom, Google Meet, and Zoom. Ipinapakita sa talahanayan ng weighted mean at bawat bahagdan ng bawat respondente na nakakuha na Mean 3.55 na kailangan pang linangin ang kanilang kaalaman sa paggamit ng online learning mode sa online class. Sa pagpapaunlad ng kaalaman at kahusayan sa pag-aaral ng asignaturang Filipino hinggil sa epekto nito. Ang talahanayan ay nagpapakita ng weighted mean at bahagdan ng mga respondente ayon sa mula sa unang aytem nito ay nakakuha ng may Mean na 4 ito ay madalas na nakaaapekto ayon sa pagpapaunlad ng kaalaman. Panghuli na posibleng rekomendasyon ang bawat talahanayan ay nagpapakita ng weighted mean at bawat bahagdan ng bawat respondente ayon sa mula sa unang aytem ito ay nakakuha ng mayroong mean na 3.475 na naaayon sa kanilang isinagot sa talatanungan.

How to Cite

- Endnote/Zotero/Mendeley (RIS)

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Journal Proposal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Characteristics of filipino online learners: a survey of science education students’ engagement, self-regulation, and self-efficacy.

1. Introduction

1.1. frameworks used in the study, 1.2. student engagement, 1.3. self-regulated learning, 1.4. self-efficacy, 1.5. research gap.

- Gender preference;

- Internet access;

- Internet signal;

- Region of residence;

- Gadgets used in online learning;

- Most preferred or best time to study online;

- Online learning tools?

- Student engagement (OSE);

- Self-regulated online learning (SROL);

- Online learning self-efficacy (OLSE)?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. research design, 2.2. research sampling and participants, 2.3. research instruments, 2.4. data gathering and ethics, 2.5. data analysis, 2.6. assumptions for manova, 2.7. process flow of this survey research, 3.1. demographic profile, 3.2. gadgets for online learning, 3.3. online learning tools, 3.4. online learning characteristics, 3.4.1. online student engagement, 3.4.2. self-regulated learning, 3.4.3. online learning self-efficacy, 3.4.4. effects of the demographic profile on ose, srol, and olse, 3.4.5. olse characteristics according to gender preference, 4. discussion, 5. conclusions, implications, and recommendations, author contributions, institutional review board statement, informed consent statement, data availability statement, acknowledgments, conflicts of interest.

- Pangeni, S.K. Open and distance learning: Cultural practices in Nepal. Eur. J. Open Distance E-Learn. 2016 , 19 , 32–45. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hasan, N.; Khan, N.H. Online teaching-learning during Covid-19 pandemic: Students’ perspective. Online J. Distance Educ. E-Learn. 2020 , 8 , 202–213. Available online: http://tojdel.net/journals/tojdel/articles/v08i04/v08i04-03.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Susila, H.R.; Qosim, A.; Rositasari, T. Students’ perception of online learning in COVID-19 pandemic: A preparation for developing a strategy for learning from home. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2020 , 8 , 6042–6047. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Sutarto, S.; Sari, D.P.; Fathurrochman, I. Teacher strategies in online learning to increase students’ interest in learning during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Konseling Pendidik. 2020 , 8 , 129–137. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Rizun, M.; Strzelecki, A. Students’ acceptance of the COVID-19 impact on shifting higher education to distance learning in Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020 , 17 , 6468. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Rapanta, C.; Botturi, L.; Goodyear, P.; Guàrdia, L.; Koole, M. Online university teaching during and after the Covid-19 crisis: Refocusing teacher presence and learning activity. Postdigit. Sci. Educ. 2020 , 2 , 923–945. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Cabaleiro-Cerviño, G.; Vera, C. The Impact of Educational Technologies in Higher Education. GIST Educ. Learn. Res. J. 2020 , 20 , 155–169. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1262695.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2023). [ CrossRef ]

- Shahabadi, M.M.; Uplane, M. Synchronous and Asynchronous E-Learning Styles and Academic Performance of e-Learners. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015 , 176 , 129–138. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ghavifekr, S.; Rosdy, W.A.W. Teaching and learning with technology: Effectiveness of ICT integration in schools. Int. J. Res. Educ. Sci. 2016 , 1 , 175–191. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1105224.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2021). [ CrossRef ]

- Ukata, P.F.; Onuekwa, F.A. Application of ICT towards minimizing traditional classroom challenges of teaching and learning during COVID-19 pandemic in Rivers State Tertiary Institutions. Int. J. Educ. Eval. 2020 , 6 , 24–39. Available online: https://www.iiardjournals.org/get/IJEE/VOL.%206%20NO.%205%202020/APPLICATION%20OF%20ICT%20TOWARDS.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2023).

- Sun, A.; Chen, X. Online education and its effective practice: A research review. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Res. 2016 , 15 , 157–190. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Rodrigues, H.; Almeida, F.; Figueiredo, V.; Lopes, S.L. Tracking e-learning through published papers: A systematic review. Comput. Educ. 2019 , 136 , 87–98. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Stephen, J.S.; Rockinson-Szapkiw, A.J.; Dubay, C. Persistence model of non-traditional online learners: Self-efficacy, self-regulation, and self-direction. Am. J. Distance Educ. 2020 , 34 , 306–321. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Manco-Chavez, J.A.; Uribe-Hernandez, Y.C.; Buendia-Aparcana, R.; Vertiz-Osores, J.J.; Alcoser, S.D.I.; Rengifo-Lozano, R.A. Integration of ICTS and digital skills in times of the pandemic COVID-19. Int. J. High. Educ. 2020 , 9 , 11. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Rahiem, M.D.H. The emergency remote learning experience of university students in Indonesia amidst COVID-19 crisis. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2020 , 16 , 1–26. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Biwer, F.; Wiradhany, W.; Oude Egbrink, M.; Hospers, H.; Wasenitz, S.; Jansen, W.; De Bruin, A. Changes and adaptations: How university students self-regulate their online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021 , 12 , 642593. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Baticulon, R.E.; Alberto, N.R.I.; Baron, M.B.C.; Mabulay, R.E.C.; Rizada, L.G.T.; Sy, J.J.; Tiu, C.J.S.; Clarion, C.A. Barriers to online learning in the time of COVID-19: A national survey of medical students in the Philippines. medRxiv 2020 . [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Juhary, J. Perceived usefulness and ease of use of the learning management system as a learning tool. Int. Educ. Stud. 2014 , 7 , 23. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hensley, L.C.; Iaconelli, R.; Wolters, C.A. “This weird time we’re in”: How a sudden change to remote education impacted college students’ self-regulated learning. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2022 , 54 (Suppl. S1), S203–S218. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Gambo, Y.; Shakir, M. Evaluating students’ experiences in self-regulated smart learning environment. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023 , 28 , 547–580. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Gonzales, K.P. Rising from Covid-19: Private schools’ readiness and response amidst a global pandemic. Int. Multidiscip. Res. J. 2020 , 2 , 81–90. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bruso, J.; Stefaniak, J.; Bol, L. An examination of personality traits as a predictor of the use of self-regulated learning strategies and considerations for online instruction. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2020 , 68 , 2659–2683. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Abou-Khalil, V.; Helou, S.; Khalifé, E.; Chen, M.A.; Majumdar, R.; Ogata, H. Emergency online learning in low-resource settings: Effective student engagement strategies. Educ. Sci. 2021 , 11 , 24. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Churiyah, M.; Sholikhan, S.; Filianti, F.; Sakdiyyah, D.A. Indonesia education readiness conducting distance learning in Covid-19 pandemic situation. Int. J. Multicult. Multireligious Underst. 2020 , 7 , 491–507. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kerr, M.S.; Rynearson, K.; Kerr, M.C. Student characteristics for online learning success. Internet High. Educ. 2006 , 9 , 91–105. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Soffer, T.; Cohen, A. Students’ engagement characteristics predict success and completion of online courses. J. Comp. Asstd. Learn. 2019 , 35 , 378–389. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Broadbent, J.; Poon, W.L. Self-regulated learning strategies and academic achievement in online higher education learning environments: A systematic review. Internet High. Educ. 2015 , 27 , 1–13. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Alqurashi, E. Self-Efficacy in online learning environments: A literature review. Contemp. Issues Educ. Res. 2016 , 9 , 45–52. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Czerkawski, B.C.; Lyman, E.W. An instructional design framework for fostering student engagement in online learning environments. TechTrends 2016 , 60 , 532–539. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Panadero, E.; Alonso-Tapia, J. How Do Students Self-Regulate? Review of Zimmerman’s Cyclical Model of Self-Regulated Learning. Ann. Psicol. 2014 , 30 , 450–462. [ Google Scholar ]

- Redmond, P.; Abawi, L.; Brown, A.; Henderson, R.; Heffernan, A. An online engagement framework for higher education. Online Learn. J. 2018 , 22 , 183–204. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psych. 2000 , 55 , 68–78. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Defnitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Cont. Educ. Psych. 2020 , 61 , 101860. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Reeve, J. A self-determination theory perspective on student engagement. In Handbook of Research on Student Engagement ; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 149–172. ISBN 978-1-4614-2017-0. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chiu, T.K.F. Applying the self-determination theory (SDT) to explain student engagement in online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2022 , 54 (Suppl. S1), S14–S30. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Gronchi, M. Self-determination, self-efficacy, and attribution in FL online learning: An exploratory survey with university students during the pandemic emergency. Studi Glottodidattica 2021 , 6 , 118–134. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Niemiec, C.P.; Lynch, M.F.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Bernstein, J.; Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The antecedents and consequences of autonomous self-regulation for college: A self-determination theory perspective on socialization. J. Adolesc. 2006 , 29 , 761–775. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Trowler, V. Student engagement literature review. High. Educ. Acad. 2010 , 11 , 1–15. Available online: https://pure.hud.ac.uk/en/publications/student-engagement-literature-review (accessed on 6 March 2021).

- Pittaway, S.M. Student and staff engagement: Developing an engagement framework in a faculty of education. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2012 , 37 , 37–45. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Meyer, K.A. Student engagement in online learning: What works and why. ASHE High. Educ. Rep. 2014 , 40 , 1–114. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bolliger, D.U.; Martin, F. Instructor and student perceptions of online student engagement strategies. Distance Educ. 2018 , 39 , 568–583. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Muir, T.; Douglas, T.; Trimble, A. Facilitation strategies for enhancing the learning and engagement of online students. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 2020 , 17 , 8. Available online: https://ro.uow.edu.au/jutlp/vol17/iss3/8 (accessed on 20 March 2021). [ CrossRef ]

- Aderibigbe, S.A. Online discussions as an intervention for strengthening students’ engagement in general education. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020 , 6 , 98. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Malan, M. Student engagement in a fully online accounting module: An action research study. S. Afr. J. High. Educ. 2020 , 34 , 112–129. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Douglas, T.; James, A.; Earwaker, L.; Mather, C.; Murray, S. Online discussion boards: Improving practice and student engagement by harnessing facilitator perceptions. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 2020 , 17 , 7. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1264456.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2021). [ CrossRef ]

- SOLAS, E.C.; Wilson, K. Lessons learned and strategies used while teaching core-curriculum science courses to english language learners at a Middle Eastern university. J. Turk. Sci. Educ. 2015 , 12 , 81–94. [ Google Scholar ]

- Delfino, A. Student engagement and academic performance of students of Partido State University. Asian J. Univ. Educ. 2019 , 15 , n1. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1222588.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Rodgers, T. Student engagement in the e-learning process and the impact on their grades. Int. J. Cyber Soc. Educ. 2008 , 1 , 143–156, ATISR. Available online: https://www.learntechlib.org/p/209167/ (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Barnard-Brak, L.; Paton, V.O.; Lan, W.Y. Profiles in self-regulated learning in the online learning environment. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2010 , 11 , 61–80. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Cai, R.; Wang, Q.; Xu, J.; Zhou, L. Effectiveness of students’ self-regulated learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Insigt. 2020 , 34 , 175–182. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Greene, J.A.; Plumley, R.D.; Urban, C.J.; Bernacki, M.L.; Gates, K.M.; Hogan, K.A.; Demetriou, C.; Panter, A.T. Modeling temporal self-regulatory processing in a higher education biology course. Learn. Instr. 2021 , 72 , 101201. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Azizah, U.; Nasrudin, H. Metacognitive skills and self-regulated learning in pre-service teachers: Role of metacognitive-based teaching materials. J. Turk. Sci. Educ. 2021 , 18 , 461–476. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Anderton, B. Using the online course to promote self-regulated learning strategies in pre-service teachers. J. Inter. Online Learn. 2006 , 5 , 156–177. Available online: https://www.ncolr.org/jiol/issues/pdf/5.2.3.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2023).

- Martín-del-Pozo, M.; Martín-Sánchez, I. Self-assessment and pre-Service teachers’ self-regulated learning in a school organisation course in hybrid learning. J. Inter. Media Educ. 2022 , 1 , 1–15. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lewis, J.P.; Litchfield, B.C. Effects of self-regulated learning strategies on preservice teachers in an educational technology course. Education 2011 , 132 , 455–464. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kibirige, I.; Odora, R.J. Pre-service Teachers’ Use and Usefulness of Blackboard Learning Management Systems for Self-Regulated Learning. J. Educ. Technol. 2023 , 7 , 226–234. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ejubovic, A.; Puška, A. Impact of self-regulated learning on academic performance and satisfaction of students in the online environment. Knowl. Manag. E-Learn. 2019 , 11 , 345–363. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Sletten, S.R. Investigating flipped learning: Student self-regulated learning, perceptions, and achievement in an introductory biology course. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2017 , 26 , 347–358. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Cho, M.-H.; Kim, B.J. Students’ self-regulation for interaction with others in online learning environments. Internet High. Educ. 2013 , 17 , 69–75. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Aşkar, P.; Umay, A. Perceived computer self-efficacy of the students in the elementary mathematics teaching programme. Hacet. Univ. J. Educ. 2001 , 21 , 1–8. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Self-efficacy and educational development. Self-Effic. Chang. Soc. 1995 , 1 , 202–231. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Elstad, E.; Christophersen, K.-A. Perceptions of digital competency among student teachers: Contributing to the development of student teachers’ instructional self-Efficacy in technology-rich classrooms. Educ. Sci. 2017 , 7 , 27. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Peechapol, C.; Na-Songkhla, J.; Sujiva, S.; Luangsodsai, A. An exploration of factors influencing self-efficacy in online learning: A systematic review. Int. J. Emer. Technol. Learn. 2018 , 13 , 64. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lee, D.; Watson, S.L.; Watson, W.R. The relationships between self-Efficacy, task value, and self-regulated learning strategies in massive open online courses. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2020 , 21 , 23–39. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Robledo, D.A.; Miguel, F.; Arizala-Pillar, G.; Errabo, D.D.; Cajimat, R.; Prudente, M.; Aguja, S. Students’ knowledge gains, self-efficacy, perceived level of engagement, and perceptions with regard to home-based biology experiments (HBEs). J. Turk. Sci. Educ. 2023 , 20 , 84–118. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Funa, A.; Gabay, R.; Deblois, E.; Lerios, L.; Jetomo, F. Exploring Filipino preservice teachers’ online self-regulated learning skills and strategies amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc. Sci. Hum. Open. 2023 , 7 , 100470. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Lord, H.G. Ex Post Facto Studies as a Research Method. Special Report No. 7320; 1973; ERIC. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED090962.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2023).

- Joaquin, J.J.B.; Biana, H.T.; Dacela, M.A. The Philippine higher education sector in the time of COVID-19. Front. Educ. 2020 , 5 , 208. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016 , 5 , 1–4. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Statista. Perception on the effectiveness of current distance learning compared to face-to-face schooling in the Philippines as of April 2021. Educ. Sci. 2023 . Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1262427/philippines-view-on-effectiveness-of-distance-learning-compared-to-face-to-face-schooling/ (accessed on 6 October 2023).

- Dixson, M.D. Measuring student engagement in the online course: The online student engagement scale (OSE). Online Learn. 2015 , 19 , n4. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1079585.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2021). [ CrossRef ]

- Jansen, R.S.; Van Leeuwen, A.; Janssen, J.; Kester, L.; Kalz, M. Validation of the self-regulated online learning questionnaire. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2017 , 29 , 6–27. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zimmerman, W.A.; Kulikowich, J.M. Online learning self-efficacy in students with and without online learning experience. Am. J. Distance Educ. 2016 , 30 , 180–191. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Jin, W.; Prudente, M.S.; Aguja, S.E. Students’ experiences and perceptions on the use of mobile devices for learning. Adv. Sci. Lett. 2018 , 24 , 8507–8510. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Barbour, M.; Plough, C. Helping to make online learning less isolating. TechTrends 2009 , 53 , 57. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/download/79948695/Barbour2009.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- Buelow, J.R.; Barry, T.; Rich, L.E. Supporting learning engagement with online students. Online Learn. 2018 , 22 , 313–340. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Briones, M.R.B.; Errabo, D.D.R. Student’s voice of e-learning: Implication to online teaching practice. In Proceedings of the ICMET 2021: 2021 3rd International Conference on Modern Educational Technology (ICMET 2021), Jakarta, Indonesia, 21–23 May 2021; Association of Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Yavuzalp, N.; Bahcivan, E. The online learning self-efficacy scale: Its adaptation into Turkish and interpretation according to various variables. Turk. Online J. Distance Educ. 2020 , 21 , 31–44. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Beltran-Cruz, M.; Cruz, S.B.B. The use of internet-based social enhancing student’s learning experiences in biological sciences. High. Learn. Res. Com. 2013 , 3 , 68–80. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Alexiou, A.; Paraskeva, F. Enhancing self-regulated learning skills through the implementation of an e-portfolio tool. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2010 , 2 , 3048–3054. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Dianati, S.; Iwashita, N.; Vasquez, C. Flipped classroom experiences: Comparing undergraduate and postgraduate perceptions of self-regulated learning. Issues Educ. Res. 2022 , 32 , 473–493. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tanti; Maison; Mukminin, A.; Syahria; Habibi, A.; Syamsurizal, S. Exploring the relationship between preservice science teachers’ beliefs and self-regulated strategies of studying physics: A structural equation model. J. Turk. Sci. Educ. 2018 , 15 , 79–92. [ Google Scholar ]

Click here to enlarge figure

| Demographics | Number of Respondents | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | 18–22 years old | 350 | 94.09 |

| 23–26 years old | 21 | 5.65 | |

| 27 years old and above | 1 | 0.26 | |

| Gender preference | Women | 157 | 42.20 |

| Men | 186 | 49.19 | |

| LGBTQ+ | 29 | 7.80 | |

| Internet access | Via school access | 4 | 1.08 |

| Via home broadband | 222 | 59.67 | |

| Via mobile data | 146 | 39.25 | |

| Internet signal | Poor (B/s) | 35 | 9.41 |

| Good (KB/s) | 182 | 48.92 | |

| Better (MB/s) | 147 | 39.52 | |

| Best (GB/s) | 8 | 2.15 | |

| Region of residence | National Capital Region (NCR) | 183 | 49.19 |

| Region I—Ilocos Region | 2 | 0.54 | |

| Region III—Central Luzon | 33 | 8.87 | |

| Region IV-A—CALABARZON | 66 | 17.74 | |

| Region V—Bicol Region | 8 | 2.15 | |

| Region VIII—Eastern Visayas | 39 | 10.48 | |

| Region IX—Zamboanga Peninsula | 1 | 0.27 | |

| Region XIII—CARAGA | 38 | 10.22 | |

| MIMAROPA | 2 | 0.54 | |

| Most preferred time to study online | Morning | 91 | 24.46 |

| Afternoon | 58 | 15.86 | |

| Evening | 173 | 46.51 | |

| Dawn | 49 | 13.17 | |

| Characteristics | (5) Very Characteristic of Me (%) | (4) Characteristic of Me (%) | (3) Moderately Characteristic of Me (%) | (2) Not Really Characteristic of Me (%) | (1) Not at All Characteristic of Me (%) | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Making sure to study on a regular basis | 20.70 | 43.55 | 27.96 | 7.26 | 0.54 | ||

| 2. Putting forth effort | 30.65 | 48.12 | 18.28 | 2.42 | 0.54 | ||

| 3. Keeping up with the readings | 14.78 | 35.48 | 36.83 | 10.75 | 2.15 | ||

| 4. Looking over class notes before going online to make sure I understand the material | 26.88 | 44.62 | 25.00 | 3.23 | 0.27 | ||

| 5. Being organized | 30.65 | 40.86 | 22.04 | 4.03 | 2.42 | ||

| 6. Taking good notes on readings, PowerPoints, or video lectures | 27.96 | 36.56 | 27.96 | 6.45 | 1.08 | ||

| 7. Listening/reading carefully | 32.53 | 47.31 | 17.74 | 2.15 | 0.27 | ||

| 8. Finding ways to make the course material relevant to my life | 28.23 | 41.67 | 23.39 | 5.38 | 1.34 | ||

| 9. Applying the course material to my life | 23.92 | 43.28 | 26.08 | 5.91 | 0.81 | ||

| 10. Finding ways to make the course material relevant to me | 25.54 | 46.77 | 21.77 | 4.84 | 1.08 | ||

| 11. Having a strong desire to learn the material | 28.76 | 45.16 | 22.58 | 2.69 | 0.81 | ||

| 12. Having fun when engaging in online chats, discussions, or email with the instructor or classmates | 25.81 | 39.52 | 23.92 | 8.33 | 2.42 | ||

| 13. Participating actively in small-group discussion forums | 20.70 | 41.94 | 27.15 | 7.80 | 2.42 | ||

| 14. Helping fellow students | 40.59 | 40.32 | 15.32 | 2.96 | 0.81 | ||

| 15. Attaining a good grade | 30.11 | 48.39 | 18.28 | 2.69 | 0.54 | ||

| 16. Achieving good results on tests/quizzes | 20.70 | 52.96 | 22.85 | 2.69 | 0.81 | ||

| 17. Engaging in conversations online (chats/discussions, email, etc.) | 25.54 | 41.40 | 24.19 | 6.72 | 2.15 | ||

| 18. Posting in the discussion forum regularly | 14.78 | 26.61 | 37.63 | 12.63 | 8.33 | ||

| 19. Getting to know other students in the class | 27.96 | 38.71 | 20.97 | 8.33 | 4.03 | ||

| Characteristics | (5) Very True for Me (%) | (4) True for Me (%) | (3) Moderately True for Me (%) | (2) Not Really True for Me (%) | (1) Not at All True for Me (%) | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I think about what I really need to learn before I begin a task in this online course. | 26.34 | 45.16 | 24.73 | 3.76 | 0 | ||

| 2. I ask myself questions about what I will be studying before I begin learning in this online course. | 25.54 | 44.62 | 25.81 | 3.49 | 0.54 | ||

| 3. I set short-term (daily or weekly) goals as well as long-term goals (monthly or for the whole online course). | 23.12 | 42.47 | 25.27 | 6.99 | 2.15 | ||

| 4. I set goals to help me manage my studying time for this online course. | 35.84 | 37.63 | 19.35 | 5.91 | 1.61 | ||

| 5. I set specific goals before I begin a task in this online course. | 27.42 | 42.47 | 23.12 | 6.18 | 0.81 | ||

| 6. I think of alternative ways of solving a problem and choose the best one for this online course. | 30.38 | 49.19 | 18.55 | 1.88 | 0 | ||

| 7. I try to use strategies in this online course that have worked in the past. | 31.18 | 44.89 | 19.62 | 3.76 | 0.54 | ||

| 8. I have a specific purpose for each strategy I use in this online course. | 22.58 | 45.16 | 27.15 | 4.84 | 0.27 | ||

| 9. I am aware of what strategies I use when I study for this online course. | 20.97 | 47.58 | 26.34 | 4.03 | 1.08 | ||

| 10. Although we do not have to attend daily classes, I still try to distribute my studying time for this online course evenly throughout the days of the week. | 20.43 | 43.28 | 27.15 | 6.99 | 2.15 | ||

| 11. I periodically review to help me understand important relationships in this online course. | 17.74 | 45.70 | 27.42 | 8.06 | 1.08 | ||

| 12. I find myself pausing regularly to check my comprehension of this online course. | 22.31 | 44.89 | 26.34 | 5.38 | 1.08 | ||

| 13. I ask myself questions about how well I am performing while learning something in this online course. | 27.15 | 43.01 | 24.73 | 4.84 | 0.27 | ||

| 14. I think about what I have learned after I finish working on material in this online course. | 22.58 | 48.39 | 23.12 | 5.38 | 0.54 | ||

| 15. I ask myself how well I accomplished my goals once I have finished working on material in this online course. | 24.73 | 49.46 | 22.31 | 3.23 | 0.27 | ||

| 16. I change strategies when I do not make progress while learning in this online course. | 27.96 | 42.74 | 23.12 | 5.11 | 1. 08 | ||

| 17. I find myself analyzing the usefulness of strategies while I study for this online course. | 23.12 | 47.04 | 24.73 | 4.57 | 0.54 | ||

| 18. I ask myself if there were other ways to complete things after I finish learning material from this online course. | 24.19 | 47.85 | 23.12 | 3.76 | 1.08 | ||

| 19. I find it difficult to stick to a study schedule for this online course. | 30.65 | 38.17 | 22.04 | 7.80 | 1.34 | ||

| 20. I make sure I keep up with weekly readings and assignments for this online course. | 25.27 | 45.70 | 21.77 | 5.91 | 1.34 | ||

| 21. I often find that I do not spend very much time on this online course because of other activities. | 22.58 | 37.10 | 28.49 | 9.41 | 2.42 | ||

| 22. I choose a location where I can avoid an excessive amount of distraction when studying for this online course. | 39.78 | 32.80 | 19.89 | 6.18 | 1.34 | ||

| 23. I try to find a comfortable place to study for this online course. | 37.90 | 33.60 | 19.89 | 6.18 | 2.42 | ||

| 24. I know where I can study most efficiently for this online course. | 29.03 | 39.52 | 24.19 | 5.91 | 1.34 | ||

| 25. I have a regular place set aside for studying for this online course. | 27.96 | 41.94 | 20.43 | 7.53 | 2.15 | ||

| 26. I know what the instructor expects me to learn in this online course. | 20.16 | 44.35 | 30.11 | 4.84 | 0.54 | ||

| 27. When I am feeling bored when studying for this online course, I force myself to pay attention. | 22.04 | 36.83 | 28.69 | 9.41 | 4.03 | ||

| 28. When my mind begins to wander during a learning session for this online course, I make a special effort to keep concentrating. | 22.04 | 42.47 | 27.42 | 6.72 | 1.34 | ||

| 29. When I begin to lose interest for this online course, I push myself even further. | 23.92 | 35.48 | 29.30 | 8.87 | 2.42 | ||

| 30. I work hard to perform well in this online course even if I do not like the tasks I have to perform. | 29.57 | 43.28 | 21.24 | 4.84 | 1.08 | ||

| 31. Even when materials in this online course are dull and uninteresting, I manage to keep working until I finish. | 26.88 | 43.82 | 22.04 | 6.18 | 1.08 | ||

| 32. When I do not fully understand something, I ask other course members in this online course for ideas. | 33.87 | 38.44 | 21.24 | 4.57 | 1.88 | ||

| 33. I share my problems with my classmates in this course online so that we know what we are struggling with and how to solve our problems. | 31.99 | 32.53 | 22.04 | 8.87 | 4.57 | ||

| 34. I am persistent in receiving help from the instructor of this online course. | 18.01 | 35.22 | 31.99 | 8.06 | 6.72 | ||

| 35. When I am not sure about material in this online course, I check with other people. | 31.99 | 40.59 | 21.51 | 3.23 | 2.69 | ||

| 36. I communicate with my classmates to find out how I am performing in this online course. | 37.75 | 30.65 | 23.66 | 4.57 | 5.38 | ||

| Characteristics | (4) Strongly Agree (%) | (3) Agree (%) | (2) Disagree (%) | (1) Strongly Disagree (%) | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I can navigate online course materials efficiently | 31.99 | 58.60 | 9.41 | 0 | ||

| 2. I can find the course syllabus online | 36.02 | 53.49 | 9.41 | 1.08 | ||

| 3. I can effectively communicate with my instructor via e-mail | 26.08 | 48.12 | 23.92 | 1.88 | ||

| 4. I can communicate effectively with technical support via e-mail or live online chat | 27.69 | 48.12 | 20.97 | 3.23 | ||

| 5. I can submit assignments using an online drop box | 45.70 | 41.94 | 10.75 | 1.61 | ||

| 6. I can overcome technical difficulties on my own | 37.90 | 50.00 | 11.02 | 1.08 | ||

| 7. I can navigate the online grade book | 26.34 | 55.11 | 16.13 | 2.42 | ||

| 8. I manage my time effectively | 33.33 | 43.82 | 17.74 | 5.11 | ||

| 9. I complete all assignments on time | 39.25 | 44.09 | 13.71 | 2.96 | ||

| 10. I am able learn how to use a new type of technology efficiently | 43.01 | 45.97 | 10.22 | 0.81 | ||

| 11. I can learn without being in the same room as the instructor | 26.34 | 52.69 | 18.82 | 2.15 | ||

| 12. I can learn without being in the same room as the other students | 27.42 | 51.34 | 18.28 | 2.96 | ||

| 13. I often search the internet to find the answer to a course-related question | 37.90 | 48.12 | 11.83 | 2.15 | ||

| 14. I often search the online course materials | 40.32 | 48.66 | 10.48 | 0.54 | ||

| 15. I often communicate using asynchronous technologies (discussion boards, e-mail, etc.) | 33.87 | 50.54 | 12.90 | 2.69 | ||

| 16. I meet deadlines with very few reminders | 30.11 | 54.03 | 13.17 | 2.69 | ||

| 17. I can complete a group project entirely online | 38.71 | 49.73 | 11.02 | 0.54 | ||

| 18. I use synchronous technology (such as Skype) to communicate with others | 47.04 | 44.89 | 7.80 | 0.27 | ||

| 19. I can focus on schoolwork when faced with distractions | 25.00 | 49.46 | 20.70 | 4.84 | ||

| 20. I often develop and follow a plan for completing all required work on time | 30.91 | 55.91 | 12.37 | 0.81 | ||

| 21. I use the library’s online resources efficiently | 20.97 | 42.20 | 24.19 | 12.63 | ||

| 22. When a problem arises, I promptly ask questions in the appropriate forum (e-mail, discussion board, etc.) | 35.48 | 44.35 | 17.20 | 2.96 | ||

| Characteristics | Men | Women | LGBTQ+ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| 1. I can navigate online course materials efficiently | 3.29 | 0.60 | 3.26 | 0.61 | 2.97 | 0.50 |

| 2. I can find the course syllabus online | 3.20 | 0.73 | 3.32 | 0.59 | 3.14 | 0.58 |

| 3. I can communicate effectively with my instructor via e-mail | 2.97 | 0.80 | 3.01 | 0.71 | 2.93 | 0.80 |

| 4. I can communicate effectively with technical support via e-mail or live online chat | 3.01 | 0.77 | 3.00 | 0.80 | 3.00 | 0.79 |

| 5. I can submit assignments using an online drop box | 3.26 | 0.76 | 3.36 | 0.68 | 3.41 | 0.73 |

| 6. I can overcome technical difficulties on my own | 3.28 | 0.68 | 3.24 | 0.69 | 3.07 | 0.70 |

| 7. I can navigate the online grade book | 3.03 | 0.74 | 3.10 | 0.67 | 3.00 | 0.89 |

| 8. I manage my time effectively | 3.08 | 0.86 | 3.04 | 0.84 | 2.97 | 0.78 |

| 9. I complete all assignments on time | 3.26 | 0.79 | 3.16 | 0.79 | 2.97 | 0.91 |

| 10. I can learn to use a new type of technology efficiently | 3.32 | 0.64 | 3.30 | 0.74 | 3.31 | 0.66 |

| 11. I can learn without being in the same room as the instructor | 3.10 | 0.72 | 2.98 | 0.71 | 3.90 | 0.90 |

| 12. I can learn without being in the same room as the other students | 3.09 | 0.74 | 2.99 | 0.75 | 3.90 | 0.90 |

| 13. I often search the internet to find the answer to a course-related question | 3.20 | 0.75 | 3.27 | 0.70 | 3.03 | 0.78 |

| 14. I often search for the online course materials | 3.26 | 0.69 | 3.33 | 0.63 | 3.24 | 0.74 |

| 15. I often communicate using asynchronous technologies (discussion boards, e-mail, etc.) | 3.18 | 0.74 | 3.20 | 0.69 | 2.79 | 0.94 |

| 16. I meet deadlines with very few reminders | 3.11 | 0.73 | 3.15 | 0.71 | 2.97 | 0.82 |

| 17. I can complete a group project entirely online | 3.31 | 0.67 | 3.21 | 0.66 | 3.28 | 0.70 |

| 18. I use synchronous technology to communicate with others (such as Skype) | 3.35 | 0.65 | 3.43 | 0.61 | 3.34 | 0.72 |

| 19. I can focus on schoolwork when faced with distractions | 3.06 | 0.77 | 2.85 | 0.83 | 2.72 | 0.84 |

| 20. I often develop and follow a plan for completing all required work on time | 3.17 | 0.65 | 3.20 | 0.67 | 2.97 | 0.78 |

| 21. I use the library’s online resources efficiently | 2.70 | 0.98 | 2.76 | 0.87 | 2.59 | 1.02 |

| 22. When a problem arises, I promptly ask questions in the appropriate forum (e-mail, discussion board, etc.) | 3.18 | 0.79 | 3.10 | 0.79 | 2.90 | 0.82 |

| The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

Share and Cite

Briones, M.R.; Prudente, M.; Errabo, D.D. Characteristics of Filipino Online Learners: A Survey of Science Education Students’ Engagement, Self-Regulation, and Self-Efficacy. Educ. Sci. 2023 , 13 , 1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111131

Briones MR, Prudente M, Errabo DD. Characteristics of Filipino Online Learners: A Survey of Science Education Students’ Engagement, Self-Regulation, and Self-Efficacy. Education Sciences . 2023; 13(11):1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111131

Briones, Mary Rose, Maricar Prudente, and Denis Dyvee Errabo. 2023. "Characteristics of Filipino Online Learners: A Survey of Science Education Students’ Engagement, Self-Regulation, and Self-Efficacy" Education Sciences 13, no. 11: 1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111131

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

- Title & authors

Ignacio, Aris E. "Online Classes and Learning in the Philippines During the Covid-19 Pandemic." International Journal on Integrated Education , vol. 4, no. 3, 2021, pp. 1-6, doi: 10.31149/ijie.v4i3.1301 .

Download citation file:

The COVID-19 pandemic brought great disruption to all aspects of life specifically on how classes were conducted both in an offline and online modes. The sudden shift to purely online method of teaching and learning was a result of the lockdowns that were imposed by the Philippine government. While some institutions have dealt with the situation by shutting down operations, others continued to deliver instructions and lessons using the Internet and different applications that support online learning. The continuation of classes online had caused several issues from students and teachers ranging from lack of technology to mental health matters. Finally, recommendations were asserted to mitigate the presented concerns and improve the delivery of the necessary quality education to the intended learners.

Table of contents

Exploring the Online Learning Experience of Filipino College Students During Covid-19 Pandemic

- Louie Giray College of Education, Polytechnic University of the Philipines, Taguig City, Philippines

- Daxjhed Gumalin College of Education, Polytechnic University of the Philipines, Taguig City, Philippines

- Jomarie Jacob College of Education, Polytechnic University of the Philipines, Taguig City, Philippines

- Karl Villacorta College of Education, Polytechnic University of the Philipines, Taguig City, Philippines

This study was endeavored to understand the online learning experience of Filipino college students enrolled in the academic year 2020-2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic. The data were obtained through an open-ended qualitative survey. The responses were analyzed and interpreted using thematic analysis. A total of 71 Filipino college students from state and local universities in the Philippines participated in this study. Four themes were classified from the collected data: (1) negative views toward online schooling, (2) positive views toward online schooling, (3) difficulties encountered in online schooling, and (4) motivation to continue studying. The results showed that although many Filipino college students find online learning amid the COVID-19 pandemic to be a positive experience such as it provides various conveniences, eliminates the necessity of public transportation amid the COVID-19 pandemic, among others, a more significant number of respondents believe otherwise. The majority of the respondents shared a general difficulty adjusting toward the new online learning setup because of problems related to technology and Internet connectivity, mental health, finances, and time and space management. A large portion of students also got their motivation to continue studying despite the pandemic from fear of being left behind, parental persuasion, and aspiration to help the family.

- EndNote - EndNote format (Macintosh & Windows)

- ProCite - RIS format (Macintosh & Windows)

- Reference Manager - RIS format (Windows only)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License .

Authors who publish with this journal agree to the following terms: (1) Authors retain copyright and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC-BY-SA) that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this journal; (2) Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the journal's published version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial publication in this journal; (3) Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work ( See The Effect of Open Access ).

Content Use Policy

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Study Protocol

Assessing the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic, shift to online learning, and social media use on the mental health of college students in the Philippines: A mixed-method study protocol

Roles Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft

Affiliation College of Medicine, University of the Philippines, Manila, Philippines

Roles Methodology, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Department of Clinical Epidemiology, College of Medicine, University of the Philippines, Manila, Philippines, Institute of Clinical Epidemiology, National Institutes of Health, University of the Philippines, Manila, Philippines

Roles Methodology

Affiliation Department of Psychiatry, College of Medicine, University of the Philippines, Manila, Philippines

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

- Leonard Thomas S. Lim,

- Zypher Jude G. Regencia,

- J. Rem C. Dela Cruz,

- Frances Dominique V. Ho,

- Marcela S. Rodolfo,

- Josefina Ly-Uson,

- Emmanuel S. Baja

- Published: May 3, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0267555

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic declared by the WHO has affected many countries rendering everyday lives halted. In the Philippines, the lockdown quarantine protocols have shifted the traditional college classes to online. The abrupt transition to online classes may bring psychological effects to college students due to continuous isolation and lack of interaction with fellow students and teachers. Our study aims to assess Filipino college students’ mental health status and to estimate the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic, the shift to online learning, and social media use on mental health. In addition, facilitators or stressors that modified the mental health status of the college students during the COVID-19 pandemic, quarantine, and subsequent shift to online learning will be investigated.

Methods and analysis

Mixed-method study design will be used, which will involve: (1) an online survey to 2,100 college students across the Philippines; and (2) randomly selected 20–40 key informant interviews (KIIs). Online self-administered questionnaire (SAQ) including Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21) and Brief-COPE will be used. Moreover, socio-demographic factors, social media usage, shift to online learning factors, family history of mental health and COVID-19, and other factors that could affect mental health will also be included in the SAQ. KIIs will explore factors affecting the student’s mental health, behaviors, coping mechanism, current stressors, and other emotional reactions to these stressors. Associations between mental health outcomes and possible risk factors will be estimated using generalized linear models, while a thematic approach will be made for the findings from the KIIs. Results of the study will then be triangulated and summarized.

Ethics and dissemination

Our study has been approved by the University of the Philippines Manila Research Ethics Board (UPMREB 2021-099-01). The results will be actively disseminated through conference presentations, peer-reviewed journals, social media, print and broadcast media, and various stakeholder activities.

Citation: Lim LTS, Regencia ZJG, Dela Cruz JRC, Ho FDV, Rodolfo MS, Ly-Uson J, et al. (2022) Assessing the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic, shift to online learning, and social media use on the mental health of college students in the Philippines: A mixed-method study protocol. PLoS ONE 17(5): e0267555. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0267555

Editor: Elisa Panada, UNITED KINGDOM

Received: June 9, 2021; Accepted: April 11, 2022; Published: May 3, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Lim et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: This project is being supported by the American Red Cross through the Philippine Red Cross and Red Cross Youth. The funder will not have a role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak as a global pandemic, and the Philippines is one of the 213 countries affected by the disease [ 1 ]. To reduce the virus’s transmission, the President imposed an enhanced community quarantine in Luzon, the country’s northern and most populous island, on March 16, 2020. This lockdown manifested as curfews, checkpoints, travel restrictions, and suspension of business and school activities [ 2 ]. However, as the virus is yet to be curbed, varying quarantine restrictions are implemented across the country. In addition, schools have shifted to online learning, despite financial and psychological concerns [ 3 ].

Previous outbreaks such as the swine flu crisis adversely influenced the well-being of affected populations, causing them to develop emotional problems and raising the importance of integrating mental health into medical preparedness for similar disasters [ 4 ]. In one study conducted on university students during the swine flu pandemic in 2009, 45% were worried about personally or a family member contracting swine flu, while 10.7% were panicking, feeling depressed, or emotionally disturbed. This study suggests that preventive measures to alleviate distress through health education and promotion are warranted [ 5 ].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers worldwide have been churning out studies on its psychological effects on different populations [ 6 – 9 ]. The indirect effects of COVID-19, such as quarantine measures, the infection of family and friends, and the death of loved ones, could worsen the overall mental wellbeing of individuals [ 6 ]. Studies from 2020 to 2021 link the pandemic to emotional disturbances among those in quarantine, even going as far as giving vulnerable populations the inclination to commit suicide [ 7 , 8 ], persistent effect on mood and wellness [ 9 ], and depression and anxiety [ 10 ].

In the Philippines, a survey of 1,879 respondents measuring the psychological effects of COVID-19 during its early phase in 2020 was released. Results showed that one-fourth of respondents reported moderate-to-severe anxiety, while one-sixth reported moderate-to-severe depression [ 11 ]. In addition, other local studies in 2020 examined the mental health of frontline workers such as nurses and physicians—placing emphasis on the importance of psychological support in minimizing anxiety [ 12 , 13 ].

Since the first wave of the pandemic in 2020, risk factors that could affect specific populations’ psychological well-being have been studied [ 14 , 15 ]. A cohort study on 1,773 COVID-19 hospitalized patients in 2021 found that survivors were mainly troubled with fatigue, muscle weakness, sleep difficulties, and depression or anxiety [ 16 ]. Their results usually associate the crisis with fear, anxiety, depression, reduced sleep quality, and distress among the general population.

Moreover, the pandemic also exacerbated the condition of people with pre-existing psychiatric disorders, especially patients that live in high COVID-19 prevalence areas [ 17 ]. People suffering from mood and substance use disorders that have been infected with COVID-19 showed higher suicide risks [ 7 , 18 ]. Furthermore, a study in 2020 cited the following factors contributing to increased suicide risk: social isolation, fear of contagion, anxiety, uncertainty, chronic stress, and economic difficulties [ 19 ].

Globally, multiple studies have shown that mental health disorders among university student populations are prevalent [ 13 , 20 – 22 ]. In a 2007 survey of 2,843 undergraduate and graduate students at a large midwestern public university in the United States, the estimated prevalence of any depressive or anxiety disorder was 15.6% and 13.0% for undergraduate and graduate students, respectively [ 20 ]. Meanwhile, in a 2013 study of 506 students from 4 public universities in Malaysia, 27.5% and 9.7% had moderate and severe or extremely severe depression, respectively; 34% and 29% had moderate and severe or extremely severe anxiety, respectively [ 21 ]. In China, a 2016 meta-analysis aiming to establish the national prevalence of depression among university students analyzed 39 studies from 1995 to 2015; the meta-analysis found that the overall prevalence of depression was 23.8% across all studies that included 32,694 Chinese university students [ 23 ].

A college student’s mental status may be significantly affected by the successful fulfillment of a student’s role. A 2013 study found that acceptable teaching methods can enhance students’ satisfaction and academic performance, both linked to their mental health [ 24 ]. However, online learning poses multiple challenges to these methods [ 3 ]. Furthermore, a 2020 study found that students’ mental status is affected by their social support systems, which, in turn, may be jeopardized by the COVID-19 pandemic and the physical limitations it has imposed. Support accessible to a student through social ties to other individuals, groups, and the greater community is a form of social support; university students may draw social support from family, friends, classmates, teachers, and a significant other [ 25 , 26 ]. Among individuals undergoing social isolation and distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, social support has been found to be inversely related to depression, anxiety, irritability, sleep quality, and loneliness, with higher levels of social support reducing the risk of depression and improving sleep quality [ 27 ]. Lastly, it has been shown in a 2020 study that social support builds resilience, a protective factor against depression, anxiety, and stress [ 28 ]. Therefore, given the protective effects of social support on psychological health, a supportive environment should be maintained in the classroom. Online learning must be perceived as an inclusive community and a safe space for peer-to-peer interactions [ 29 ]. This is echoed in another study in 2019 on depressed students who narrated their need to see themselves reflected on others [ 30 ]. Whether or not online learning currently implemented has successfully transitioned remains to be seen.

The effect of social media on students’ mental health has been a topic of interest even before the pandemic [ 31 , 32 ]. A systematic review published in 2020 found that social media use is responsible for aggravating mental health problems and that prominent risk factors for depression and anxiety include time spent, activity, and addiction to social media [ 31 ]. Another systematic review published in 2016 argues that the nature of online social networking use may be more important in influencing the symptoms of depression than the duration or frequency of the engagement—suggesting that social rumination and comparison are likely to be candidate mediators in the relationship between depression and social media [ 33 ]. However, their findings also suggest that the relationship between depression and online social networking is complex and necessitates further research to determine the impact of moderators and mediators that underly the positive and negative impact of online social networking on wellbeing [ 33 ].

Despite existing studies already painting a picture of the psychological effects of COVID-19 in the Philippines, to our knowledge, there are still no local studies contextualized to college students living in different regions of the country. Therefore, it is crucial to elicit the reasons and risk factors for depression, stress, and anxiety and determine the potential impact that online learning and social media use may have on the mental health of the said population. In turn, the findings would allow the creation of more context-specific and regionalized interventions that can promote mental wellness during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Materials and methods

The study’s general objective is to assess the mental health status of college students and determine the different factors that influenced them during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, it aims:

- To describe the study population’s characteristics, categorized by their mental health status, which includes depression, anxiety, and stress.

- To determine the prevalence and risk factors of depression, anxiety, and stress among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic, quarantine, and subsequent shift to online learning.

- To estimate the effect of social media use on depression, anxiety, stress, and coping strategies towards stress among college students and examine whether participant characteristics modified these associations.

- To estimate the effect of online learning shift on depression, anxiety, stress, and coping strategies towards stress among college students and examine whether participant characteristics modified these associations.

- To determine the facilitators or stressors among college students that modified their mental health status during the COVID-19 pandemic, quarantine, and subsequent shift to online learning.

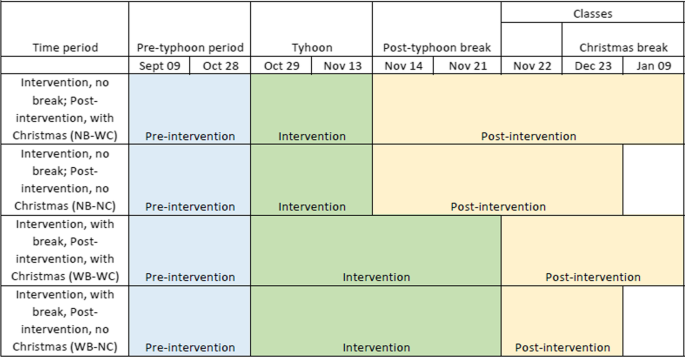

Study design

A mixed-method study design will be used to address the study’s objectives, which will include Key Informant Interviews (KIIs) and an online survey. During the quarantine period of the COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines from April to November 2021, the study shall occur with the population amid community quarantine and an abrupt transition to online classes. Since this is the Philippines’ first study that will look at the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic, quarantine, and subsequent shift to online learning, the online survey will be utilized for the quantitative part of the study design. For the qualitative component of the study design, KIIs will determine facilitators or stressors among college students that modified their mental health status during the quarantine period.

Study population

The Red Cross Youth (RCY), one of the Philippine Red Cross’s significant services, is a network of youth volunteers that spans the entire country, having active members in Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao. The group is clustered into different age ranges, with the College Red Cross Youth (18–25 years old) being the study’s population of interest. The RCY has over 26,060 students spread across 20 chapters located all over the country’s three major island groups. The RCY is heterogeneously composed, with some members classified as college students and some as out-of-school youth. Given their nationwide scope, disseminating information from the national to the local level is already in place; this is done primarily through email, social media platforms, and text blasts. The research team will leverage these platforms to distribute the online survey questionnaire.

In addition, the online survey will also be open to non-members of the RCY. It will be disseminated through social media and engagements with different university administrators in the country. Stratified random sampling will be done for the KIIs. The KII participants will be equally coming from the country’s four (4) primary areas: 5–10 each from the national capital region (NCR), Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao, including members and non-members of the RCY.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for the online survey will include those who are 18–25 years old, currently enrolled in a university, can provide consent for the study, and are proficient in English or Filipino. The exclusion criteria will consist of those enrolled in graduate-level programs (e.g., MD, JD, Master’s, Doctorate), out-of-school youth, and those whose current curricula involve going on duty (e.g., MDs, nursing students, allied medical professions, etc.). The inclusion criteria for the KIIs will include online survey participants who are 18–25 years old, can provide consent for the study, are proficient in English or Filipino, and have access to the internet.

Sample size

A continuity correction method developed by Fleiss et al. (2013) was used to calculate the sample size needed [ 34 ]. For a two-sided confidence level of 95%, with 80% power and the least extreme odds ratio to be detected at 1.4, the computed sample size was 1890. With an adjustment for an estimated response rate of 90%, the total sample size needed for the study was 2,100. To achieve saturation for the qualitative part of the study, 20 to 40 participants will be randomly sampled for the KIIs using the respondents who participated in the online survey [ 35 ].

Study procedure

Self-administered questionnaire..

The study will involve creating, testing, and distributing a self-administered questionnaire (SAQ). All eligible study participants will answer the SAQ on socio-demographic factors such as age, sex, gender, sexual orientation, residence, household income, socioeconomic status, smoking status, family history of mental health, and COVID-19 sickness of immediate family members or friends. The two validated survey tools, Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21) and Brief-COPE, will be used for the mental health outcome assessment [ 36 – 39 ]. The DASS-21 will measure the negative emotional states of depression, anxiety, and stress [ 40 ], while the Brief-COPE will measure the students’ coping strategies [ 41 ].

For the exposure assessment of the students to social media and shift to online learning, the total time spent on social media (TSSM) per day will be ascertained by querying the participants to provide an estimated time spent daily on social media during and after their online classes. In addition, students will be asked to report their use of the eight commonly used social media sites identified at the start of the study. These sites include Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn, Pinterest, TikTok, YouTube, and social messaging sites Viber/WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger with response choices coded as "(1) never," "(2) less often," "(3) every few weeks," "(4) a few times a week," and “(5) daily” [ 42 – 44 ]. Furthermore, a global frequency score will be calculated by adding the response scores from the eight social media sites. The global frequency score will be used as an additional exposure marker of students to social media [ 45 ]. The shift to online learning will be assessed using questions that will determine the participants’ satisfaction with online learning. This assessment is comprised of 8 items in which participants will be asked to respond on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree.’

The online survey will be virtually distributed in English using the Qualtrics XM™ platform. Informed consent detailing the purpose, risks, benefits, methods, psychological referrals, and other ethical considerations will be included before the participants are allowed to answer the survey. Before administering the online survey, the SAQ shall undergo pilot testing among twenty (20) college students not involved with the study. It aims to measure total test-taking time, respondent satisfaction, and understandability of questions. The survey shall be edited according to the pilot test participant’s responses. Moreover, according to the Philippines’ Data Privacy Act, all the answers will be accessible and used only for research purposes.

Key informant interviews.

The research team shall develop the KII concept note, focusing on the extraneous factors affecting the student’s mental health, behaviors, and coping mechanism. Some salient topics will include current stressors (e.g., personal, academic, social), emotional reactions to these stressors, and how they wish to receive support in response to these stressors. The KII will be facilitated by a certified psychologist/psychiatrist/social scientist and research assistants using various online video conferencing software such as Google Meet, Skype, or Zoom. All the KIIs will be recorded and transcribed for analysis. Furthermore, there will be a debriefing session post-KII to address the psychological needs of the participants. Fig 1 presents the diagrammatic flowchart of the study.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0267555.g001

Data analyses

Quantitative data..

Descriptive statistics will be calculated, including the prevalence of mental health outcomes such as depression, anxiety, stress, and coping strategies. In addition, correlation coefficients will be estimated to assess the relations among the different mental health outcomes, covariates, and possible risk factors.

Several study characteristics as effect modifiers will also be assessed, including sex, gender, sexual orientation, family income, smoking status, family history of mental health, and Covid-19. We will include interaction terms between the dichotomized modifier variable and markers of social media use (total TSSM and global frequency score) and shift to online learning in the models. The significance of the interaction terms will be evaluated using the likelihood ratio test. All the regression analyses will be done in R ( http://www.r-project.org ). P values ≤ 0.05 will be considered statistically significant.

Qualitative data.

After transcribing the interviews, the data transcripts will be analyzed using NVivo 1.4.1 software [ 50 ] by three research team members independently using the inductive logic approach in thematic analysis: familiarizing with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing the themes, defining and naming the themes, and producing the report [ 51 ]. Data familiarization will consist of reading and re-reading the data while noting initial ideas. Additionally, coding interesting features of the data will follow systematically across the entire dataset while collating data relevant to each code. Moreover, the open coding of the data will be performed to describe the data into concepts and themes, which will be further categorized to identify distinct concepts and themes [ 52 ].

The three researchers will discuss the results of their thematic analyses. They will compare and contrast the three analyses in order to come up with a thematic map. The final thematic map of the analysis will be generated after checking if the identified themes work in relation to the extracts and the entire dataset. In addition, the selection of clear, persuasive extract examples that will connect the analysis to the research question and literature will be reviewed before producing a scholarly report of the analysis. Additionally, the themes and sub-themes generated will be assessed and discussed in relevance to the study’s objectives. Furthermore, the gathering and analyzing of the data will continue until saturation is reached. Finally, pseudonyms will be used to present quotes from qualitative data.

Data triangulation.

Data triangulation using the two different data sources will be conducted to examine the various aspects of the research and will be compared for convergence. This part of the analysis will require listing all the relevant topics or findings from each component of the study and considering where each method’s results converge, offer complementary information on the same issue, or appear to contradict each other. It is crucial to explicitly look for disagreements between findings from different data collection methods because exploration of any apparent inter-method discrepancy may lead to a better understanding of the research question [ 53 , 54 ].

Data management plan.

The Project Leader will be responsible for overall quality assurance, with research associates and assistants undertaking specific activities to ensure quality control. Quality will be assured through routine monitoring by the Project Leader and periodic cross-checks against the protocols by the research assistants. Transcribed KIIs and the online survey questionnaire will be used for recording data for each participant in the study. The project leader will be responsible for ensuring the accuracy, completeness, legibility, and timeliness of the data captured in all the forms. Data captured from the online survey or KIIs should be consistent, clarified, and corrected. Each participant will have complete source documentation of records. Study staff will prepare appropriate source documents and make them available to the Project Leader upon request for review. In addition, study staff will extract all data collected in the KII notes or survey forms. These data will be secured and kept in a place accessible to the Project Leader. Data entry and cleaning will be conducted, and final data cleaning, data freezing, and data analysis will be performed. Key informant interviews will always involve two researchers. Where appropriate, quality control for the qualitative data collection will be assured through refresher KII training during research design workshops. The Project Leader will check through each transcript for consistency with agreed standards. Where translations are undertaken, the quality will be assured by one other researcher fluent in that language checking against the original recording or notes.

Ethics approval.

The study shall abide by the Principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (2013). It will be conducted along with the Guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonization-Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP), E6 (R2), and other ICH-GCP 6 (as amended); National Ethical Guidelines for Health and Health-Related Research (NEGHHRR) of 2017. This protocol has been approved by the University of the Philippines Manila Research Ethics Board (UPMREB 2021-099-01 dated March 25, 2021).

The main concerns for ethics were consent, data privacy, and subject confidentiality. The risks, benefits, and conflicts of interest are discussed in this section from an ethical standpoint.

Recruitment.

The participants will be recruited to answer the online SAQ voluntarily. The recruitment of participants for the KIIs will be chosen through stratified random sampling using a list of those who answered the online SAQ; this will minimize the risk of sampling bias. In addition, none of the participants in the study will have prior contact or association with the researchers. Moreover, power dynamics will not be contacted to recruit respondents. The research objectives, methods, risks, benefits, voluntary participation, withdrawal, and respondents’ rights will be discussed with the respondents in the consent form before KII.

Informed consent will be signified by the potential respondent ticking a box in the online informed consent form and the voluntary participation of the potential respondent to the study after a thorough discussion of the research details. The participant’s consent is voluntary and may be recanted by the participant any time s/he chooses.

Data privacy.

All digital data will be stored in a cloud drive accessible only to the researchers. Subject confidentiality will be upheld through the assignment of control numbers and not requiring participants to divulge the name, address, and other identifying factors not necessary for analysis.

Compensation.

No monetary compensation will be given to the participants, but several tokens will be raffled to all the participants who answered the online survey and did the KIIs.

This research will pose risks to data privacy, as discussed and addressed above. In addition, there will be a risk of social exclusion should data leaks arise due to the stigma against mental health. This risk will be mitigated by properly executing the data collection and analysis plan, excluding personal details and tight data privacy measures. Moreover, there is a risk of psychological distress among the participants due to the sensitive information. This risk will be addressed by subjecting the SAQ and the KII guidelines to the project team’s psychiatrist’s approval, ensuring proper communication with the participants. The KII will also be facilitated by registered clinical psychologists/psychiatrists/social scientists to ensure the participants’ appropriate handling; there will be a briefing and debriefing of the participants before and after the KII proper.

Participation in this study will entail health education and a voluntary referral to a study-affiliated psychiatrist, discussed in previous sections. Moreover, this would contribute to modifications in targeted mental-health campaigns for the 18–25 age group. Summarized findings and recommendations will be channeled to stakeholders for their perusal.

Dissemination.

The results will be actively disseminated through conference presentations, peer-reviewed journals, social media, print and broadcast media, and various stakeholder activities.

This study protocol rationalizes the examination of the mental health of the college students in the Philippines during the COVID-19 pandemic as the traditional face-to-face classes transitioned to online and modular classes. The pandemic that started in March 2020 is now stretching for more than a year in which prolonged lockdown brings people to experience social isolation and disruption of everyday lifestyle. There is an urgent need to study the psychosocial aspects, particularly those populations that are vulnerable to mental health instability. In the Philippines, where community quarantine is still being imposed across the country, college students face several challenges amidst this pandemic. The pandemic continues to escalate, which may lead to fear and a spectrum of psychological consequences. Universities and colleges play an essential role in supporting college students in their academic, safety, and social needs. The courses of activities implemented by the different universities and colleges may significantly affect their mental well-being status. Our study is particularly interested in the effect of online classes on college students nationwide during the pandemic. The study will estimate this effect on their mental wellbeing since this abrupt transition can lead to depression, stress, or anxiety for some students due to insufficient time to adjust to the new learning environment. The role of social media is also an important exposure to some college students [ 55 , 56 ]. Social media exposure to COVID-19 may be considered a contributing factor to college students’ mental well-being, particularly their stress, depression, and anxiety [ 57 , 58 ]. Despite these known facts, little is known about the effect of transitioning to online learning and social media exposure on the mental health of college students during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines. To our knowledge, this is the first study in the Philippines that will use a mixed-method study design to examine the mental health of college students in the entire country. The online survey is a powerful platform to employ our methods.