Improve your Grades

Essay on Video Games Addiction | Video Games Addiction Essay for Students and Children in English

October 21, 2024 by Prasanna

Essay on Video Games Addiction: In a world where the youth are already struggling with different types of addictions, the emergence of video game addictions is an unwelcome addition. Every day there seems to be a rise in the number of video game addicts. Be it children, teenagers, and even adults. Video games are very entertaining and can hook anyone of any age in. Especially since a person’s emotions are involved in it. It is very easy to get hooked and spend hours and hours playing video games.

There needs to be regulation of the time spent playing video games and intervention from friends and family if they see someone whose life revolves around the video games they play. Addictions do not affect only the person who is addicted. Like any other, this addiction can take over a person’s life and affect their education, work, family life, and the lives of those who love them.

You can also find more Essay Writing articles on events, persons, sports, technology and many more.

Long and Short Essays on Video Games Addiction for Students and Kids in English

We provide children and students with essay samples on a long essay of 500 words and a short essay of 150 words on the topic “Video Game Addiction” for reference.

Short Essay on Video Games Addiction 150 Words in English

Short Essay on Video Games Addiction is usually given to classes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6.

Video games are a great source of entertainment and a way to fight boredom. They also help people wind down and relax after a stressful day at work. Gaming communities can also often be a safe space for individuals to make friends and interact with peers. However, there are also negative consequences of spending too much time playing video games. Gamer Rage is a well-known thing that can have adverse effects. Individuals that experience this can end up destroying things at home and even hurting family members.

In other words, excessive gaming can cause great harm. People who spend hours and hours on end playing video games can lose their bearings in the real world when they get off the game. They can find themselves disoriented and unable to function normally. This means that there must be some self-control when gaming, not to let it consume a person’s life.

Introduction

Video game addiction is as harmful an addiction as any other. Individuals even suffer from withdrawal syndrome if they are away from their consoles or systems for too long. Those who are addicted end up playing video games for multiple hours at a stretch without taking a break except for something necessary.

Most video games rely on the gamer coming back to beat the next high score or make the next discovery for open-world games. For those who are a part of gaming communities, it is about beating the next team together and gaining more resources or whatever else it is that is required in the game to advance. This is especially true for role-playing games where the player can customize their character and interact with others.

One of the main problems resulting from excessive gaming is gamer rage that comes from frustration and anger when a player cannot beat their opponent. It results in swearing and abusing opponents and family members verbally. They also sometimes end up attacking family members if the game happens to be cut short or if they are asked to leave the game to tend to their other duties for some time.

Physical Consequences

This addiction can result in carpal tunnel syndrome, poor eyesight, migraines, backaches, pain from poor posture, and even obesity and cardiovascular diseases. With a lack of routine in the outside world, it can have significant physical consequences.

Those who play video games need to be mindful of the amount of time that is spent. They also need to be careful that they do not neglect other responsibilities that they may have. Especially for those who have young children at home that cannot be ignored.

Long Essay on Video Games Addiction 500 Words in English

Long Essay on Video Games Addiction is usually given to classes 7, 8, 9, and 10.

Video games are a fun and entertaining way to relax. They help people who are isolated to form friends and be a part of a community. There are many stories where children with developmental issues learn how to interact and be a part of society. It helps them with brain development and helps them grow in many ways. However, there is a downside to it, with excessive gaming that can result in addiction. This is an extreme that we cannot go to as it harms everyone involved.

Massive Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games play a huge role in players that get addicted to gaming. In this sort of gaming, the player can create their character and play with others on quests to get better gear. These are games that one pays for, which means that there is a waste of money if a person isn’t playing. That, coupled with how enjoyable the game is, can result in players playing for hours on end. The visuals’ effects and quality are generally very high in these, which makes gameplay all the more captivating. It is difficult for players to reorient themselves when they come back to the real world.

As unique and fun as the games are, this is also a problem that needs to be addressed. Precisely because the games are so enjoyable that players find it difficult to disconnect and be a part of the real world.

Social Consequences

People often find a way to balance their time to either go to work or school, finish what they have to do, come home, and spend all their time playing games. Often they think that this is a good compromise. It is not.

It is not healthy to divide life between the two in that manner. There needs to be a balance where individuals spend time with their family and friends as well. This can result in isolation in social life and regression in learning how to function in society. This can result in behavioral issues as well. When teenagers spend time in this manner, they do not learn the basic skills required to function in society and to hold jobs.

This is an issue that affects individuals that are married as well. There are many stories where the spouse works through the day and comes home and plays, neglecting the house or the children. Resulting in one parent handling all the load of the house, which is extremely stressful and challenging. It can lead to a break in relationships as well.

When a person spends hours gaming, they give no time to walking around or any physical activity. It can lead to poor eyesight, carpal tunnel syndrome, and pain and aches due to bad posture. It can lead to migraines and, in extreme cases, neurological issues. Not walking around can result in obesity, cardiovascular diseases, and posture issues for years. Gamer rage can also result in strokes.

Mental Consequences

Many times, gamers find it difficult to be a part of the real world after gaming for so many hours. They tend to try functioning in the real world as they would in games. In this manner, they can harm themselves and other people. Like the incident of the boy who shot a random person on the street expecting him to become a zombie as people were doing in the game that he was playing. This is an extreme case of disorientation and disconnect from the real world.

Addiction can also result in paranoia and anxiety if excessive time is spent playing intense games. It can also lead to mental regression and a loss of social skills.

Fortunately, rehab centers for this addiction also exist so that people who seek help can go back to having a normal life. Even so, rehabs are not a guarantee of freedom, and therefore people must be careful and practice self-control themselves when it comes to how much time is spent playing video games.

Video Games Addiction Essay Conclusion

While video games are an excellent source for an individual to be able to wind down and relax and entertainment, there still needs to be control and regulation. Excessive gaming can result in the development of an addiction, which can severely hamper a person’s growth and well-being. Video games are a tool that is meant to be used for fun or to connect with other people. But it becomes a significant issue if we let this become a lifestyle. It also disrupts family life. Therefore, this is an issue that we need to deal with so that it doesn’t take over people’s lives and futures.

- Picture Dictionary

- English Speech

- English Slogans

- English Letter Writing

- English Essay Writing

- English Textbook Answers

- Types of Certificates

- ICSE Solutions

- Selina ICSE Solutions

- ML Aggarwal Solutions

- HSSLive Plus One

- HSSLive Plus Two

- Kerala SSLC

- Distance Education

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

15.9 Cause-and-Effect Essay

Learning objective.

- Read an example of the cause-and-effect rhetorical mode.

Effects of Video Game Addiction

Video game addition is a serious problem in many parts of the world today and deserves more attention. It is no secret that children and adults in many countries throughout the world, including Japan, China, and the United States, play video games every day. Most players are able to limit their usage in ways that do not interfere with their daily lives, but many others have developed an addiction to playing video games and suffer detrimental effects.

An addiction can be described in several ways, but generally speaking, addictions involve unhealthy attractions to substances or activities that ultimately disrupt the ability of a person to keep up with regular daily responsibilities. Video game addiction typically involves playing games uncontrollably for many hours at a time—some people will play only four hours at a time while others cannot stop for over twenty-four hours. Regardless of the severity of the addiction, many of the same effects will be experienced by all.

One common effect of video game addiction is isolation and withdrawal from social experiences. Video game players often hide in their homes or in Internet cafés for days at a time—only reemerging for the most pressing tasks and necessities. The effect of this isolation can lead to a breakdown of communication skills and often a loss in socialization. While it is true that many games, especially massive multiplayer online games, involve a very real form of e-based communication and coordination with others, and these virtual interactions often result in real communities that can be healthy for the players, these communities and forms of communication rarely translate to the types of valuable social interaction that humans need to maintain typical social functioning. As a result, the social networking in these online games often gives the users the impression that they are interacting socially, while their true social lives and personal relations may suffer.

Another unfortunate product of the isolation that often accompanies video game addiction is the disruption of the user’s career. While many players manage to enjoy video games and still hold their jobs without problems, others experience challenges at their workplace. Some may only experience warnings or demerits as a result of poorer performance, or others may end up losing their jobs altogether. Playing video games for extended periods of time often involves sleep deprivation, and this tends to carry over to the workplace, reducing production and causing habitual tardiness.

Video game addiction may result in a decline in overall health and hygiene. Players who interact with video games for such significant amounts of time can go an entire day without eating and even longer without basic hygiene tasks, such as using the restroom or bathing. The effects of this behavior pose significant danger to their overall health.

The causes of video game addiction are complex and can vary greatly, but the effects have the potential to be severe. Playing video games can and should be a fun activity for all to enjoy. But just like everything else, the amount of time one spends playing video games needs to be balanced with personal and social responsibilities.

Online Cause-and-Effective Essay Alternatives

Lawrence Otis Graham examines racism, and whether it has changed since the 1970s, in The “Black Table” Is Still There :

- http://scremeens.googlepages.com/TheBlackTableessay.rtf

Robin Tolmach Lakoff discusses the power of language to dehumanize in From Ancient Greece to Iraq: The Power of Words in Wartime :

- http://www.nytimes.com/2004/05/18/science/essay-from-ancient-greece-to-iraq-the-power-of-words-in-wartime.html

Alan Weisman examines the human impact on the planet and its effects in Earth without People :

- http://discovermagazine.com/2005/feb/earth-without-people

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Escaping through virtual gaming—what is the association with emotional, social, and mental health? A systematic review

Lucas m marques, pedro m uchida, felipe o aguiar, gabriel kadri, raphael i m santos, sara p barbosa.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Edited by: Joao Ricardo Nickenig Vissoci, Duke University, United States

Reviewed by: Paulo Guirro Laurence, Mackenzie Presbyterian University, Brazil; Ilaria Maria Antonietta Benzi, University of Pavia, Italy

*Correspondence: Lucas M. Marques, [email protected]

Received 2023 Jul 12; Accepted 2023 Oct 17; Collection date 2023.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

The realm of virtual games, video games, and e-sports has witnessed remarkable and substantial growth, captivating a diverse and global audience. However, some studies indicate that this surge is often linked to a desire to escape from real life, a phenomenon known as escapism. Much like substance abuse, escapism has been identified as a significant motivator, leading to adverse outcomes, including addiction. Therefore, it is crucial to comprehend the existing research on the connection between escapism and engagement in virtual gaming. This understanding can shed light on the reasons behind such practices and their potential impact on mental and public health.

The objective of this systematic review is investigate the findings pertaining to association between escapism and the practice of virtual games, such as video-games and e-sport.

PUBMED and SCOPUS database were systematically searched. Six independent researchers screened articles for relevance. We extracted data regarding escapism-related measures, emotional/mental health-related measures and demographic information relevant to the review purpose.

The search yielded 357 articles, 36 were included. Results showed that: (i) Escapist motivation (EM) is one of the main motives for playing virtual games; (ii) EM is related to negative clinical traits; (iii) EM predicts negative psychological/emotional/mental health outcomes; (iv) EM is associated with impaired/negative perception of the real-world life; (v) EM predicts non-adaptive real social life; and (vi) EM is associated with dysfunctional gaming practices in some cases. However, EM can have beneficial effects, fostering confidence, determination, a sense of belonging in virtual communities, and representation through avatars. Furthermore, the reviewed findings suggest that EM was positively linked to mitigating loneliness in anxious individuals and promoting social activities that preserved mental health among typical individuals during the pandemic.

Our review reinforces the evidence linking EM in the context of virtual games to poor mental health and non-adaptive social behavior. The ensuing discussion explores the intricate connection between escapism and mental health, alongside examining the broad implications of virtual gaming practices on underlying motivations for escapism in the realms of social cognition, health promotion, and public health.

Keywords: escapism, virtual games, video-game, E-sport, emotion regulation, mental health, health promotion, gamification

Introduction

It is well-established how games and virtual reality have become integral parts of our lives. Similarly, the increasing number of games being used for treatment or interventions to aid individuals with neurological disabilities ( 1 ), neurocognitive disorders ( 2 ), or to improve physical health ( 3 ) has gained prominence.

In the USA, a country with one of the largest numbers of players globally, approximately 97% of children and adolescents spend at least one hour playing video games daily ( 4 ). Motivations for playing include stress relief, the challenge of games, social interaction, with older adults more likely to cite cognitive benefits ( 5 ). Additionally, other studies have highlighted reasons such as escapism, achievement, and competition ( 6 , 7 ).

As presented by Zanetta et al. ( 7 ), typically 10 motivations can be observed among online gaming players: (i) Advancement: Becoming powerful; (ii) Mechanics: How interested are you in the precise numbers and percentages underlying the game mechanics?; (iii) Competition: Doing things that annoy other players; (iv) Socializing: Getting to know other players; (v) Relationship: How often do you talk to your online friends about your personal issues?; (vi) Teamwork: Would you rather be grouped or soloing?; (vii) Discovery: How much do you enjoy exploring the world just for the sake of exploring it?; (viii) Role-Playing: How often do you role-play your character?; (ix) Customization: How important is it to you that your character’s armor/outfit matches in color and style?; and (x) Escapism: Escaping from the real world.

In the field of game studies, one term that has garnered significant interest is ‘escapism,’ which can be defined as the pursuit of escaping from real life into another fictional world ( 8 ). Recent research has sought to associate gaming motives with narcissism through escapism ( 9 ), coping strategies with negative outcomes related to escapism ( 10 ), gaming escapism as a factor for Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) development ( 11 ), the moderating effect of escapism on the relationship between loneliness and negative outcomes ( 12 ), difficulties in emotion regulation ( 13 ), and the motive of competition as a strong predictor of IGD ( 14 ). Additionally, this phenomenon of escapism is also observed in other areas of life, such as addiction to alcohol ( 15 , 16 ), dance ( 17 ), pornography ( 18 ) and social networks ( 19 ).

Lastly, recent research has indicated that gaming escapism can be also associated with excessive gambling ( 20 ) and addictive gaming behavior ( 21 ). Furthermore, it has been observed that negative outcomes of gaming, influenced by escapism motives, may be exacerbated by factors such as social anxiety ( 22 ) a competitive background ( 14 ), existing psychiatric distress ( 23 ) and low self-concept clarity ( 24 ).

It is essential to emphasize that escapism, when applied to gaming, does not inherently carry a negative connotation. It can also serve as an emotional regulation strategy, encompassing attentional distraction during emotionally intense situations and emotional suppression following an already established emotional impact ( 25 ). Moreover, restricting our understanding of escapism in gaming to its negative connotation can unfairly characterize gaming solely as a negative activity. However, gaming is not exclusively an act of escapism but can also be motivated by a quest for enjoyment and diversion ( 8 ).

Hence, to comprehensively assess the positive or negative nature of the association between Escapist Motivation (EM) and mental health, it is essential to consider various factors, including the cultural context in which gaming practices occur ( 26 ).

Considering the abundance of studies that have explored the relationship between escapism and the engagement in virtual games, it is now opportune to examine the emotional, social, and mental health impacts arising from gaming practices driven by escapism motives. Therefore, this systematic review aims to consolidate key studies linking virtual gaming practices with escapism, with the intent of evaluating whether escapism indeed serves as a determinant of such practices and whether these activities have a positive or negative effect on mental health. As previously mentioned, among various motivators for online gaming, we have chosen to focus on Escapism in this study. Unlike other potential motivators that often exhibit adaptive behaviors and are associated with positive orientations, such as the pursuit of novelty, building new relationships, and curiosity, Escapism appears to be characterized by a desire to distance oneself from reality. This tendency may stem from a limited emotional and psychological toolkit for coping with the real world.

In this context, drawing from existing literature, we anticipate discovering negative correlations between Escapist Motivation (EM) and aspects conducive to effective social adaptation, such as the cultivation of social skills, emotional regulation abilities, and overall well-being. Conversely, addiction-related behaviors like Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD), social withdrawal, feelings of loneliness, heightened stress, as well as elevated levels of anxiety and depression, are expected to exhibit a positive association with EM. These are, however, hypotheses that underpin the rationale for this systematic review, which aims to unveil various novel facets integral to the ongoing discourse on this subject.

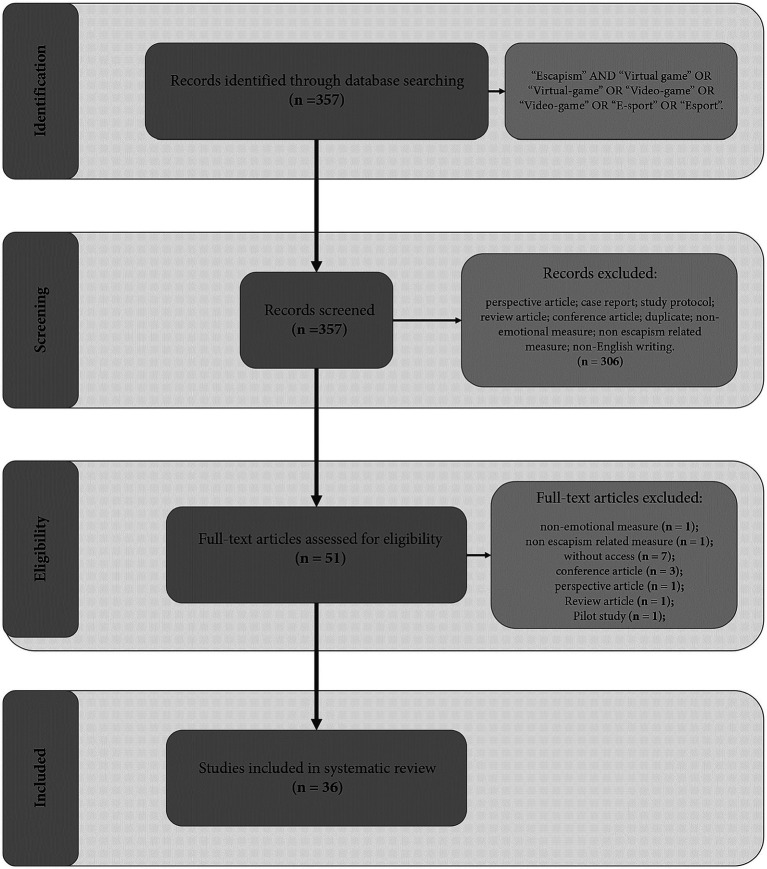

Literature search

We conducted a comprehensive systematic search in the SCOPUS and PubMed databases using specific keywords: ‘Escapism,’ AND ‘Virtual game,’ OR ‘Virtual-game,’ OR ‘Video-game,’ OR ‘Video-game,’ OR ‘E-sport,’ OR ‘Esport.’ These keywords were applied to identify relevant articles with these terms in their titles, abstracts, or keywords. The search was conducted from May 10th to May 12th, 2023, without additional filters, such as publication year. Additionally, a manual search was performed to identify potential articles through references cited within selected articles.

Literature selection: inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included all original studies that explored the potential correlation between Escapism and the practice of virtual games. These encompassed studies considering Escapism as a motive or motivator for gaming, as well as those assessing the use of Escapism as a coping strategy resulting from gaming practices. Eligibility for inclusion was limited to articles written in English. Consequently, articles with the following characteristics were excluded: (i) perspective articles, (ii) case reports, (iii) study protocols, (iv) review articles, (v) conference articles, (vi) non-emotional/social/mental health related measures, and (vii) articles written in languages other than English.

To ensure accuracy and consistency in the study selection process, duplicated records were removed, and six authors independently screened all titles and abstracts using the predetermined framework and selection criteria. Following the title and abstract selection phase, the full texts of the selected articles were obtained and analyzed. Any discrepancies were resolved through consensus among all authors.

Data extraction

Following a comprehensive examination of the articles, the authors meticulously identified and gathered the most pertinent data concerning the association between Escapism and the practice of virtual games. The data collection and review procedures were independently carried out by six authors. To extract essential information needed to define the connection between Escapism and virtual game practice, a structured list of variables was employed. The variables were specifically tailored to capture crucial aspects relevant to this association:

Sample and experimental design : (i) Sample size; (ii) Country (iii) Characteristics that define the studied group; (iv) Adopted study design.

Escapism and emotional measures : (i) Escapism-related measures; (ii) emotional/social/mental health-related measures.

Observed effect : (i) Results observed associating Escapism and emotional/social/mental health aspects.

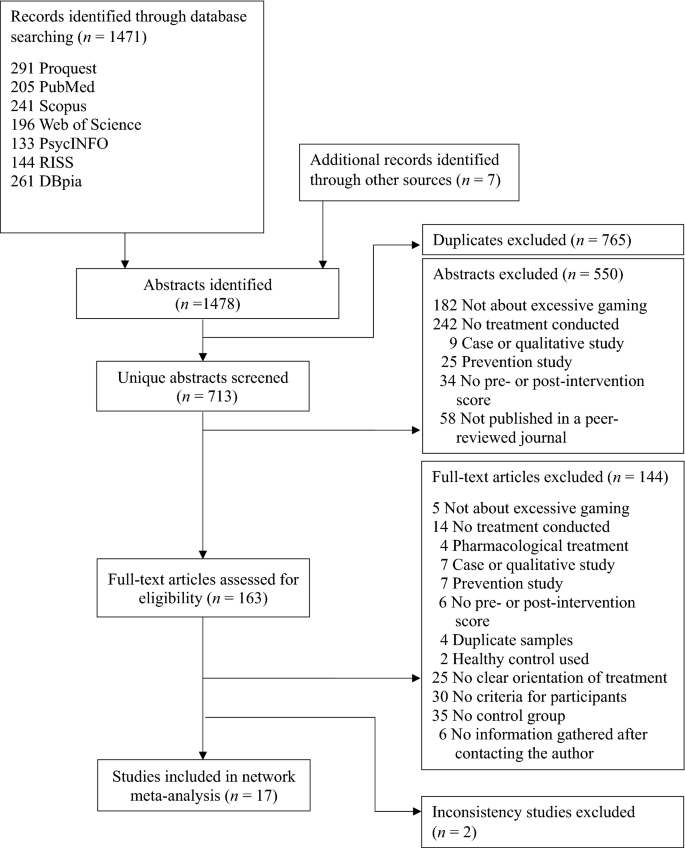

Study retrieval

The outcomes of the search strategy are succinctly presented in Figure 1 , adhering to the PRISMA statement flow diagram guidelines ( 27 ). Following the literature search, a total of 357 articles were initially identified. Through a careful screening of titles and abstracts, 306 articles were subsequently excluded. The remaining 51 articles underwent a thorough evaluation by reading their full texts. During this phase, 15 articles were further excluded as they failed to meet one or more of the specified criteria, namely: (i) utilizing non-emotional/social/mental health related measures (one article); (ii) employing non escapism-related measures (one article); (iii) lacking access to the article (seven articles); (iv) classified as a conference article (three articles); (v) classified as a perspective article (one article); (vi) classified as a review article (one article); (vii) classified as a pilot study (one article). Ultimately, a total of 36 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis (refer to Table 1 for details).

Flow diagram.

Data extraction.

Demographic findings

Among the extracted information in the present study, there were 3 data related to demographic findings, such as: (i) country; (ii) sample size; (iii) which group characterized the study sample.

In reference to the focal country of the study, we observe:

Australia – three articles ( 10 , 22 , 31 ); Croatia – one article ( 39 ); Finland – one article ( 20 ); Germany – two articles ( 9 , 47 ); Hungary – one article ( 23 ); Italy – three articles ( 13 , 14 , 51 ); Japan – one article ( 30 ); Malaysia – one article ( 41 ); Netherlands – two articles ( 28 , 38 ); Poland – two articles ( 34 , 36 ); Singapore – one article ( 42 ); South Korea – one article ( 40 ); Spain – one article ( 33 ); Sweden – two articles ( 37 , 45 ); Switzerland – one article ( 7 ); Taiwan – three articles ( 11 , 12 , 52 ); The United States of America – four articles ( 43 , 44 , 48 , 49 ); Multiple countries – five articles ( 21 , 24 , 29 , 46 , 50 ).

Furthermore, it is important to emphasize the fact that some of the articles obtained data via internet questionnaires, thus collecting data beyond their intended country.

Sample size

Regarding the sample size, the articles presented a total sample of 40,514 participants ( M = 1,095,1; SD = 2,333.8; minimum = 10, maximum = 13,464). The characteristics of the reported samples were collected based on three categories: gender, age, and center characteristics. Regarding gender, the total participants showed a predominance of male individuals (72.2%), with females accounting for only 23.7% of the total participants in the study, while others (4.1%) could not access the data or identified with another gender.

In the age category, we distributed all studies into 4 groups: (i) Children (0–12 years) (ii) Adolescents (12–18 years) (iii) Adults (18–65 years) (iv) Older adults (older than 65 years). Thus, we observed the following distribution of articles: Adolescents – three articles ( 28 , 42 , 48 ); Adolescents and adults – eleven articles ( 7 , 9 , 12 , 23 , 33 , 34 , 37 , 38 , 40 , 43 , 45 ); Adolescents, adults and older adults – one article ( 24 ); Adults – fifteen articles ( 10 , 11 , 14 , 22 , 29 – 32 , 36 , 39 , 41 , 44 , 47 , 49 , 52 ); Adults and older adults – six articles ( 13 , 20 , 21 , 46 , 50 , 51 ). Most studies included adult individuals. Only three studies focused exclusively on adolescents, and all the studies with older adults were conducted in conjunction with adults.

Sample group

Finally, regarding the center characteristics, we observed: Autism spectrum disorder – two articles ( 36 , 44 ); Internet Gaming Disorder – three articles ( 11 , 28 , 47 ); Healthy individuals – three articles ( 22 , 31 , 50 ); MMO players – one article ( 42 ); MMORPG players – seven articles ( 10 , 13 , 14 , 21 , 33 , 37 , 38 ); Recreational and e-sport players – one article ( 23 ); First person shooter players and MMORPG players – one article ( 45 ); Nonspecific players: nine articles ( 7 , 24 , 29 , 32 , 34 , 39 , 46 , 51 , 52 ); Users of virtual game live streaming services – one article ( 12 ); German internet users – one article ( 9 ); Transgender and gender-diverse – one article ( 48 ); United State residents – one article ( 49 ); Finnish residents – one article ( 20 ); University students – two articles ( 30 , 41 ); College Students – two articles ( 40 , 43 ).

Study design

Out of the 36 articles reviewed in the present study, 34 employed a cross-sectional study design, while the remaining 2 utilized prospective observational study designs.

Escapism-related measure

Among the studies analyzed, it was possible to observe that the primary measure of escapism was often the assessment of motivation for gaming—specifically, as a means to escape reality. These articles typically evaluated Escapist Motivation (EM) alongside other motivations such as coping, fantasy, skill development, recreation, competition, and social interactions. Some studies also explored escapism through open-ended interviews and specific questions dedicated to the concept of escapism.

As presented in Table 1 , we have extracted information corresponding to each specific instrument. The breakdown of measures related to escapism is as follows: Gaming Motivation Scale (GAMS) – two studies ( 36 , 38 ); Internet Gaming Disorder Scale–Short-Form (IGDS9-SF) – one study ( 24 ); Interview – four studies ( 32 , 45 , 46 , 48 ); Motivations of Play in Online Games (MPOG) – seven studies ( 10 , 12 , 20 – 22 , 33 , 34 ); Motivations To Play Inventory (MTPI) – two studies ( 37 , 51 ); Motives for Online Gaming Questionnaire (MOGQ) – seven studies ( 13 , 14 , 23 , 29 , 31 , 39 , 47 ); Open questions – 11 studies ( 7 , 9 , 28 , 30 , 40 – 44 , 49 , 52 ).

From these results, it is evident that most studies employed instruments that have been validated in existing literature, thereby enhancing the credibility of the findings. However, a notable number relied on open-ended questions and interviews. While this methodological choice provides a more comprehensive view of the phenomenon, it lacks the precision of structured instruments. Importantly, all the tools used in these studies are predicated on participants’ subjective evaluations concerning their tendencies toward escapism. They do not act as experimental measures that directly assess the escapism behaviors exhibited by participants. Such subjective evaluations might be influenced by the participants’ intentions to manage or shape the perception held by evaluators.

Emotional/social/mental health-related measure

Concerning the measures of emotional, social, and mental health employed to investigate potential associations with escapism behavior, an examination of Table 1 and the subsequent list reveals the utilization of 36 distinct instruments. Beyond these, four studies incorporated open interviews, and nine deployed open-ended questions specifically targeting escapism. In the sections that follow, we delineate each instrument and cite the respective articles that employed them.

Autistic Burnout Scale (AASPIRE) – one study ( 36 ); Addiction-Engagement Questionnaire (AEQ) – one study ( 29 ); Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) – two studies ( 23 , 47 ); Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI-18) – one study ( 47 ); Center for Epidemiological Studies’ Depression Scale (CES-D) – one study ( 11 ); Coping by Gaming Questionnaire (CGQ) – one study ( 11 ); Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS) – one study ( 20 ); Coping Orientations to Problems Experienced (COPE) – one study ( 11 ); Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation-Outcome Measure (CORE-OM) – one study ( 37 ); Depression Subscale of The Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21) – one study ( 22 ); Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS-18) – one study ( 13 ); General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) – one study ( 50 ); Internet Addiction Test (IAT) – one study ( 21 ); Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) – one study ( 20 ); Internet Gaming Disorder Scale (IGDS9) – one study ( 39 ); Internet Gaming Disorder Scale–Short-Form (IGDS9-SF) – three studies ( 9 , 14 , 24 ); Internet Gaming Disorder Test (IGDT) – two studies ( 20 , 23 ); Interview – four studies ( 32 , 45 , 46 , 48 ); Gaming Disorder Test (IGDT-10) – one study ( 23 ); Metacognitions about Desire Thinking Questionnaire (MDTQ) – one study ( 31 ); Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) – one study ( 36 ); Problematic Gaming (PG) – one study ( 20 ); Perceived Game Realism Scale (PGRS) – one study ( 34 ); Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI) – one study ( 20 ); Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) – one study ( 11 ); The Problematic Video Game Playing Test (PVGT) – one study ( 22 ); The Problem Video Game Playing Questionnaire (PVP) – one study ( 38 ); Resilience Scale (RS) – five studies ( 11 , 13 , 22 , 37 , 40 ); Self-Concept Clarity Scale (SCC) – one study ( 39 ); Steen Happiness Index (SHI) – one study ( 34 ); Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS) – one study ( 22 ); Social Phobia Scale (SPS) – two studies ( 22 , 50 ); Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) – two studies ( 37 , 50 ); Transgender Congruence Scale (TCS) – one study ( 48 ); Temporal Experience of Pleasure Scale (TEPS) – one study ( 36 ); Ten Item Personality Inventory (TIPI) – one study ( 40 ); Los Angeles Loneliness Scale Revised (ULCA) – one study ( 22 ); The Video Game Uses and Gratification Instrument (VGUGS) – one study ( 22 ); and Open questions – nine studies ( 10 , 12 , 28 , 41 – 44 , 49 , 51 ).

Predominantly, the studies under review assess dimensions pertaining to emotional and psychological health, psychiatric evaluations, social well-being, and problematic gaming. As delineated in the preceding section, measures associated with emotional, social, and mental health are largely predicated on subjective self-assessment. Consequently, these instruments do not capture clinical perceptions nor do they provide an objective quantification of the emotional state, such as would be garnered through physiological tools or implicit association tasks. Nevertheless, aside from those studies employing interviews and singular questions, all others have harnessed structured and validated instruments to gauge the specific phenomena under investigation.

Observed effect

Subsequent to detailing the instruments related to escapism and emotional, social, and mental health, we collated the findings from the 37 studies. As delineated in Table 1 , a myriad of results emerged, each unique to its respective study, necessitating the categorization of results into clusters. All authors initially undertook separate analyses, which were subsequently synthesized to formulate cohesive groupings of results.

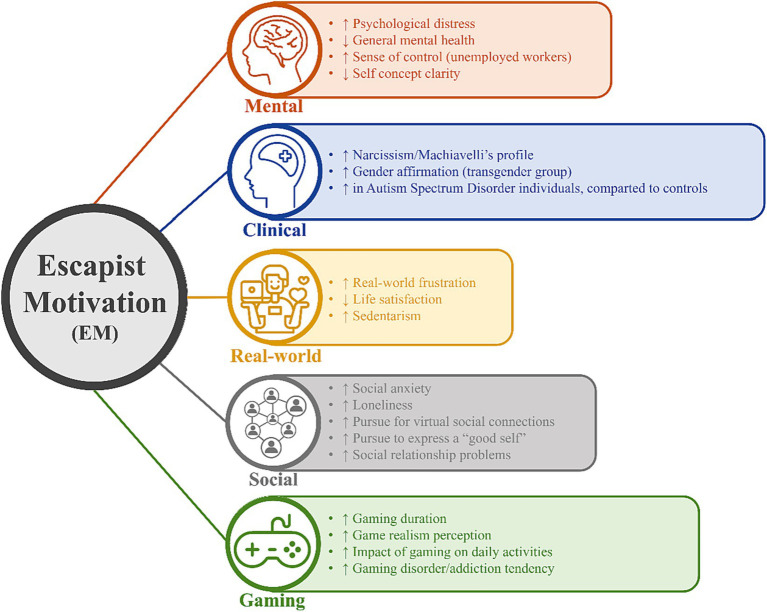

The subsequent paragraphs delineate the five distinct clusters, comprising 20 groups of findings, each associated with specific articles. Additionally, Figure 2 provides a comprehensive summary of these five clusters and their respective 20 groups of findings. It is worth mentioning that five distinct clusters were formulated, organizing the 20 findings within a theoretical framework. While it is conceivable that a finding might fit into multiple clusters, this configuration was chosen to enhance clarity and facilitate a logical comprehension of the findings. In the sections that follow, each cluster is delineated individually, accompanied by a succinct introduction explaining its thematic grouping.

Main aspects associated with Escapist Motivation (EM). The character “↑” means positive association with EM, while “↓” means negative association with EM.

The Mental cluster grouped results related to aspects of psychological well-being, mental health, and psychological processes of self-assessment. The main groups of results were: (i) EM positively associated with psychological distress – three articles ( 22 , 23 , 37 ); (ii) EM positively associated with general mental health – one article ( 50 ); (iii) EM positively associated with sense of control (unemployed workers) – one article ( 49 ); and (iv) EM negatively associated with self-concept clarity – one article ( 39 ).

In general, it is possible to understand that EM is negatively associated with aspects of good emotional/mental-health; except for the finding that EM is positively associated with a sense of control among unemployed workers ( 49 ).

The Clinical cluster aggregated findings pertinent to characteristics associated with clinical cohorts, including: (i) EM positively associated with Narcissism/Machiavelli’s profile – one article ( 9 ); (ii) EM positively associated with gender affirmation (transgender group) – one article ( 48 ); and (iii) Autism Spectrum Disorder individual present higher EM compared to controls – one article ( 44 ).

Predominantly, the evidence indicates that Escapist Motivation (EM) correlates with clinical characteristics detrimental to optimal social and emotional adaptation. An exception is observed in transgender individuals who, driven by the desire to escape reality, achieve gender affirmation and representation within games via their virtual avatars ( 44 ).

The ‘Real-world’ cluster collated findings pertinent to an individual’s perception of their immediate environment, introspective reflections on life, and strategies toward physical well-being. The results observed were: (i) EM positively associated with real-world frustration – two articles ( 32 , 35 ); EM negatively associated with life satisfaction – two articles ( 34 , 37 ); EM positively associated with sedentarism – one article ( 51 ).

Accordingly, the findings suggest that Escapist Motivation (EM) is positively correlated with a diminished subjective perception of one’s life, their surrounding environment, and personal self-care.

The ‘Social’ cluster integrated findings pertinent to an individual’s pursuit of new social affiliations, the sustenance of existing relationships, and the cultivation of a favorable perception of others. This also encompasses facets like social anxiety and perceptions of solitude. The main groups of results were: (i) EM positively associated with social anxiety – one article ( 22 ); (ii) EM positively associated with loneliness – one article ( 43 ); (iii) EM positively associated with pursue for virtual social connections – one article ( 45 ); (iv) EM positively associated with pursue to express a “good self” – one article ( 12 ); and (v) EM positively associated with social relationship problems – one article ( 51 ).

In summary, the results indicate that EM correlates with suboptimal social adaptation. Despite being associated with the pursuit of new virtual social affiliations, it can be inferred that this virtual engagement may signify an alienation from real-world connections.

Finally, concerning the ‘Gaming’ cluster, findings pertaining to gameplay, perception of this practice, and its adverse outcomes were categorized. The data reveal that (i) EM positively associated with gaming duration – two articles ( 21 , 34 ); (ii) EM positively associated with game realism perception – one article ( 34 ); (iii) EM positively associated with the impact of gaming on daily activities – eight articles ( 10 , 13 , 20 , 24 , 38 , 39 , 42 , 51 ); (iv) EM positively associated with gaming disorder/addiction tendency – six articles ( 11 , 14 , 21 , 23 , 37 , 47 ); and (v) EM is not a predictor of gaming engagement in Esports players – one article ( 41 ).

In synthesis, the findings indicate that EM is positively associated with an unhealthy practice, with excessive playing time, clinical addiction to games and skewed perceptions of gaming. It is worth mentioning the result that EM is not associated with game engagement in esports practitioners ( 41 ). This may hint that their motivation stems from other elements, including skill advancement, competitiveness, and leisure.

This review aimed to elucidate the relationship between escapist behavior in virtual games and mental health. The compilation of 36 articles predominantly utilized measures of Escapist Motivation (EM) to identify significant correlations between EM and various facets of mental health, categorized into five distinct clusters. Based on the aggregated results, it can be inferred that EM has a negative correlation with mental health outcomes, whether these pertain to gaming habits, emotional processes, ramifications on social interactions, or the nexus between real-life and virtual experiences. Nonetheless, it is worth mentioning that all findings from the reviewed articles are based on participants’ subjective self-assessments regarding their motivations to seek escape through virtual gaming. No experimental evaluations were conducted in any of the articles to empirically verify escapism behavior. Consequently, the results should be interpreted with circumspection as they represent self-reported Escapist Motivation (EM) rather than observed escapism behavior.

In the subsequent sections, we delve into the multifaceted aspects of EM. We commence with an exploration of escapism as a primary motivation for engaging in virtual games. This is followed by discussions on the association of EM with gaming practices, mental health, social well-being, and perceptions of real-world experiences. We conclude by examining the implications of escapist behavior for health promotion, public health, and clinical practice This last topic is directly aligned with the theme of this special issue in which our work is inserted.

Escapism as a motive/motivator

Predominantly, research has shown that escapism is one of the main reasons for playing virtual games. Moreover, as discerned from this review, escapism can potentially compromise a player’s health and act as a mechanism detracting from social and emotional adaptation. Some articles have observed a relationship between escapism and social anxiety ( 12 , 50 ) and loneliness ( 12 , 22 ). In multiplayer online role-playing games, these effects become more pronounced, leading to an escalation in anxiety over time when the player engages with unfamiliar participants ( 50 ). Conversely, engaging in games with acquaintances from one’s real-life social circle can enhance a player’s life satisfaction and reduce their vulnerability to social anxiety ( 50 ). When comparing Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Game (MMORPG) players with First Person Shooter (FPS) players, it was observed that MMORPG players have stronger motivations for social interaction, while FPS players reported stronger motivations for escapism ( 22 ). Additionally, MMORPG players apparently play for longer periods of time ( 22 ), perhaps due to the need for social interaction.

In our review, it was highlighted that escapism is primarily gaged using instruments assessing motivations for virtual game engagement. Not only do these studies determine if participants seek escape, but these subjective tools also report escapism as a significant reason for playing. Such self-assessments do not provide clinical insights or objective measurements of emotional states, yet they underline the escapism motive, linking it to adverse outcomes. It is imperative to differentiate between evaluating the mere effect of escapism and the underlying motivation behind it. Ultimately, the best way to determine when the practice of virtual gaming can pose a risk or benefit to mental health is by evaluating the motive or motivator.

It is important to discuss other motivations and compare them to escapism. Zanetta et al. ( 7 ) presents an extensive discussion on game motivations, proposing 10 motivations and linking them to 39 items using a factor loading scale. The 10 motivations and their strongest relationships are as follows: (i) Advancement : Becoming powerful; (ii) Mechanics : How interested are you in the precise numbers and percentages underlying the game mechanics?; (iii) Competition : Doing things that annoy other players; (iv) Socializing : Getting to know other players; (v) Relationship : How often do you talk to your online friends about your personal issues?; (vi) Teamwork : Would you rather be grouped or soloing?; (vii) Discovery : How much do you enjoy exploring the world just for the sake of exploring it?; (viii) Role-Playing : How often do you role-play your character?; (ix) Customization : How important is it to you that your character’s armor/outfit matches in color and style?; and (x) Escapism : Escaping from the real world. It is mentioned that “Several players described how these online environments provided social outlets to which they do not have access in real life. For them, MMORPGs served a much-needed social function,” indicating that “escapism” appears to be the motivator associated with negative outcomes.

Gaming practice

Considering that an important concern regarding the practice of virtual games is the development of IGD, given the results found in the present review, it is worth highlighting the association between IGD and EM.

It has been observed that Escapist Motivation is the strongest predictor of Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD), contributing with loss of control over gaming and the time spent on it ( 21 , 34 , 52 ), as well as increasing the priority of gaming upon other activities ( 10 , 13 , 20 , 24 , 38 , 39 , 42 , 51 ). Looking deeper into Escapist Motivation, it is known that different motives for escaping in gaming can lead to various outcomes when it comes to gaming practice and its characteristics ( 11 , 14 , 39 , 47 ).

While numerous factors independently predict, they gradually converge as prominent motivations for gaming, ultimately manifesting as a form of escapism. Understanding this correlation allows us to assert that factors such as autonomy, frustration, coping, competition, social motives, and fantasy pursuit can predict IGD because they are considered to be causes of Escapist Motivation ( 52 ). Individuals who feel the need to escape often turn to gaming as an option, and while this is evident, it is equally important to delve into the impact that escapism has on gaming practice characteristics. In place of regular gaming, individuals with a strong inclination for escapism are at a higher risk of developing addictive gaming habits. In such instances, gaming often takes precedence as a central activity in the individual’s life, displacing valuable time that could have been allocated to other essential life activities had problematic gaming not been a factor.

The amount of time spent on gaming activities is correlated to either online and offline social support. Increased gaming time has been observed as a predictor of lower offline social support, while being related to increased online social support from other players. Offline social support is known to promote well-being, but in certain cases in which this type of social support is not present or sufficient, online social support appears as an alternative to compensate for decreased well-being ( 34 ). Thus, individuals’ search for well-being increases gaming time.

Apart from recreational and conventional gaming, there is another gaming genre: competitive Esports. Much can be discussed about the difference between gaming for leisure and gaming as a job, but although “enjoyment, sensory experiences, emotional involvement, and arousal positively affect consumers’ esports game engagement,” research has not been able to show whether EM, role-projection and fantasy are or are not related to esports engagement ( 41 ).

Mental health

Escapism seems to mediate the relationship between real world problems and virtual game use, thus being intrinsically correlated with measures related to stress, psychological distress, mental health, and life satisfaction ( 22 , 23 , 37 , 50 ). This supports the idea that individuals with greater difficulty adapting to the real world often retreat into games, thus also correlating with narcissistic individuals, transgender individuals, and autism ( 9 , 44 , 48 ).

This relationship of poorer mental health with virtual games escapism seems to be more related to MMORPG and First-person shooter games, due to their power to escape from aversive states ( 22 ). This corroborates the research where transgender people tend to play RPG model games due to their possibility to express themselves as avatars ( 48 ). This also resonates with another observed article, showing a correlation between virtual games and a sense of control in unemployed workers, as one of the main reasons for individuals to escape from reality to the world of virtual games ( 49 ).

One detrimental aspect of EM seems to be the potential decline in self-concept clarity ( 48 ). This lack of clarity may result in individuals failing to develop effective emotional coping strategies for dealing with adverse situations in the real world, leading them to seek refuge in the realm of video games This escape does not offer genuine solutions to real-life challenges and may diminish their connection to essential social support systems due to time spent on games ( 22 ), thus intensifying psychological problems such as depression.

It is worth highlighting the lack of longitudinal studies; only one study is not cross-sectional ( 44 ). Therefore, there is a gap in understanding how these problems develop and impact mental health in the long or short term. Moreover, there is a dearth of research on the relationship between escapism and other psychological disorders, such as depression., as some studies have explored the connection between escapism and mental health, but often the participants in these studies are either generally healthy or lack confirmed diagnoses of specific psychological disorders, which can limit the broader understanding of how escapism may interact with various mental health conditions., as in the case of the studies ( 22 , 23 , 37 , 44 , 50 ).

Social health

Social health plays a pivotal role in shaping individuals’ motivations for engaging in virtual games. People with social anxiety usually have two contrasting motives: playing as a means of social interaction or playing as a form of EM. Games can assist individuals with social anxiety to better interact through the characters and story of the game. On the other hand, social anxiety could cause stress and motivate a person to play in order to avoid the judgment of other people ( 22 ). The motivation behind gaming exerts a substantial influence on several key factors, including the amount of time dedicated to gaming, the specific genre or type of game chosen, as well as an individual’s mental health and the presence of social anxiety issues. Generally, EM is associated with more severe social anxiety, playing first-person games (FPS), and spending less time playing compared to those who play for social interaction ( 22 ). Thus, the motive behind someone’s gaming habits is a crucial determinant in assessing and understanding the impact on the player’s health.

The act of playing virtual games can be erroneously associated with a solitary lifestyle. By considering various degrees of escapism, the conventional belief that psychologically and socially well-adjusted individuals derive benefits from engaging in virtual games, whereas those who are not in good health do not, is deconstructed. It becomes apparent that individuals who lead solitary lives can derive greater advantages from frequent involvement in gaming compared to their similarly isolated counterparts who engage less frequently. This phenomenon arises from the ability of virtual games to create an immersive “world” wherein individuals can experience a sense of inclusion and interact with diverse individuals. Consequently, escapism serves as a moderator of the sensation of loneliness, enabling the promotion of player immersion and compensating for the dearth of real-world interactions.

The transformations brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic in the social life of the entire world are undeniably significant. So profound are these changes that a clear distinction between the pre-pandemic and post-pandemic eras is perceptible. It is impossible to disregard the importance of virtual games during the lockdown and how escapism played a vital role in maintaining social well-being. The prevailing perception is that virtual games provided an avenue for escapism through interaction among individuals who were unable to engage in face-to-face interactions due to the lockdown, and indeed, this is true. However, another crucial factor is that escapism allows virtual game players to “escape” from the mundane, monotonous, unsatisfying, and solitary reality. Escapism aided people in maintaining social well-being in various ways, both for those who were alone at home and for those who were with their families but experiencing strained relationships. The creation of new activities in a new virtual world sustained interactions and contributed to the preservation of mental health for those who had the opportunity to engage in virtual gaming.

Therefore, playing online games is not merely about the desire to play in order to isolate oneself from social interaction; rather, it represents the arise of a new form of social interaction. Even in first-person shooter (FPS) games, the sentiments of cooperation and teamwork are crucial for achieving optimal performance in the game ( 45 ). The ability to communicate during gameplay is of great importance. Communication extends beyond in-game details and serves as a pathway for players to freely express themselves, such as sharing personal experiences from their real lives as a means of unburden ( 45 ). Furthermore, there exists the possibility for individuals to “live” in games what they are unable to experience in the real world, facilitated by new avenues where one can construct, for example, a new lifestyle, a different physical appearance, gender, or even age. Undeniably, the virtual world provided by games can be interpreted as a world where people are free to escape reality and embody different behaviors from real life, in whichever way they desire. This allows for the social experience of multiple lives within a single existence, thus creating a more democratic form of social interaction.

Real-world life

The impact of virtual gaming on real-world life can take two directions: it can be beneficial, enhancing various aspects of life, or it can move away from these potential benefits, leading to problems for gamers. Frustration in real-world life may drive gamers to spend increasingly more time gaming, causing them to become emotionally detached or absent from their own lives ( 52 ). Indeed, it can create a kind of revolving door when personal fulfillment becomes more closely linked with the virtual world, serving as an escape from negative thoughts and challenges in real life. In this scenario, individuals may become so engrossed in the virtual realm that they forget about their real-life concerns, effectively “living” in a more desirable virtual world ( 32 ).

Even though escapism from real life thought gaming may seem like an appealing option, it can have adverse effects on the well-being of individuals who are isolated users with low self-esteem ( 53 ) and for emotionally sensitive players these “virtual” places must be mediated by social spaces to prevent negative impacts on their real-world well-being ( 54 ). Moreover, when the virtual world starts to blur with reality, players may inadvertently neglect themselves, their relationships, and essential self-care activities. Additionally, there is evidence of increased dissociative experiences, such as depersonalization and derealization ( 55 ).

Health promotion, public health, and clinical practice

Based on the findings discussed in the preceding sections, it is apparent that the practice of virtual gaming, primarily driven by escapist behavior, can have significant implications for public health. As presented in the introduction of this work, the practice of virtual gaming has become increasingly prevalent worldwide, cutting across various social classes, genders, and age groups ( 56 ). This expansion, in tandem with the gaming industry’s growth, coincides with the increasing body of research highlighting the advantages of gamification in enhancing well-being and promoting health ( 57 – 59 ). However, it is imperative to consider other facets of this growth, including the potential negative consequences associated with the practice of virtual gaming. These adverse effects can encompass physical health implications, along with impacts on emotional, social, and mental well-being, as well as the broader influence on social processes and even the sociocultural development ( 60 , 61 ). The present work observed that the practice of virtual games driven by the primary motivation of escaping from reality can not only signal potential harm to the individual’s mental state but also indicate possible adverse effects on their socialization and overall well-being. Consequently, it becomes evident that the impact of virtual gaming on mental health is contingent upon a thorough assessment of the underlying motives and motivators driving its practice.

Broadly understanding these findings, virtual games represent a readily accessible activity, often without time restrictions and available for at-home consumption. When engaged in as a form of escapism, they have the potential to negatively affect the mental health of a significant portion of the population, although not necessarily following a clear causal pathway. It is important to note that this study does not aim to categorize gaming as a direct threat to public mental health but rather to highlight the risks associated with non-adaptive motivations, which can subtly contribute to mental health challenges. Additionally, clinical professionals should consider the aggregated findings when working with patients who engage in virtual gaming. Future research should explore these impacts more comprehensively through experimental investigations, focusing on emotional, social, mental, and real-life aspects of individuals practicing virtual games for escapism.

Limitations

The primary limitation of this study pertains to the diverse instruments used in the research to assess potential associations between EM and emotional, social, and mental health. As evident from our results, some studies employed well-established and validated tools like the Gaming Motivation Scale (GAMS), Internet Gaming Disorder Scale–Short-Form (IGDS9-SF), Motives for Online Gaming Questionnaire (MOGQ), among others. Conversely, certain studies relied on interviews and open-ended questions to gauge EM. While interviews and open questions offer the advantage of capturing nuanced aspects that structured instruments might miss, they present challenges when it comes to integrating findings for comparison, as was done in this review. Consequently, the choice of assessment instrument may have influenced the interpretation of certain phenomena discussed in this study, potentially hindering direct comparisons across studies. Nonetheless, since our study’s primary objective was to compile and analyze findings concerning the association between EM and emotional, social, and mental health, we believe that including studies with varied methodologies, despite their inherent limitations, enriches both the quantitative and qualitative evaluation of the phenomena. Lastly, we chose not to conduct an official quality assessment due to the experience we had with an article recently published ( 62 ). The definition of quality is very heterogeneous, and achieving an assessment that takes into account the differences between papers ends up disregarding the qualities of others. Thus, to ensure the quality of the papers included in the study, we therefore chose to include only articles from reputable journals that have undergone the peer review process.

Our review underscores the evidence that Escapist Motivation (EM) for virtual gaming correlates with negative and maladaptive mental health, social health, and gaming outcomes. Furthermore, while the results do not confirm a direct causal relationship between virtual gaming driven by EM and its outcomes, they were rigorously analyzed in the context of their potential implications for public health, mental health, and clinical practice, especially regarding the desire to escape real-world challenges.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/ Supplementary material , further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

LM: Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration. PU: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. LM was supported by a postdoctoral research grant #2021/05897-5, São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP). SB was supported by a postdoctoral research grant #2020/08512-4, São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1257685/full#supplementary-material

- 1. Mat Rosly M, Mat Rosly H, Davis Oam GM, Husain R, Hasnan N. Exergaming for individuals with neurological disability: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. (2017) 39:727–35. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2016.1161086, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Swinnen N, Vandenbulcke M, de Bruin ED, Akkerman R, Stubbs B, Firth J, et al. The efficacy of exergaming in people with major neurocognitive disorder residing in long-term care facilities: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Alzheimers Res Ther. (2021) 13:70. doi: 10.1186/s13195-021-00806-7, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Schättin A, Pickles J, Flagmeier D, Schärer B, Riederer Y, Niedecken S, et al. Development of a novel home-based Exergame with on-body feedback: usability study. JMIR Serious Games. (2022) 10:e38703. doi: 10.2196/38703, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Granic I, Lobel A, Engels RCME. The benefits of playing video games. Am Psychol. (2014) 69:66–78. doi: 10.1037/a0034857 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Whitbourne SK, Ellenberg S, Akimoto K. Reasons for playing casual video games and perceived benefits among adults 18 to 80 years old. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. (2013) 16:892–7. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0705, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Demetrovics Z, Urbán R, Nagygyörgy K, Farkas J, Zilahy D, Mervó B, et al. Why do you play? The development of the motives for online gaming questionnaire (MOGQ). Behav Res Methods. (2011) 43:814–25. doi: 10.3758/s13428-011-0091-y [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Zanetta Dauriat F, Zermatten A, Billieux J, Thorens G, Bondolfi G, Zullino D, et al. Motivations to play specifically predict excessive involvement in massively multiplayer online role-playing games: evidence from an online survey. Eur Addict Res. (2011) 17:185–9. doi: 10.1159/000326070, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Calleja G. Digital Games and Escapism. Games Cult. (2010) 5:335–53. doi: 10.1177/1555412009360412 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Tang WY, Reer F, Quandt T. The interplay of gaming disorder, gaming motivations, and the dark triad. J Behav Addict. (2020) 9:491–6. doi: 10.1556/2006.2020.00013, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Bowditch L, Chapman J, Naweed A. Do coping strategies moderate the relationship between escapism and negative gaming outcomes in world of Warcraft (MMORPG) players? Comput Hum Behav. (2018) 86:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.04.030 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Lin P-C, Yen JY, Lin HC, Chou WP, Liu TL, Ko CH. Coping, resilience, and perceived stress in individuals with internet gaming disorder in Taiwan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:1771. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18041771, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Chen C-Y, Chang S-L. Moderating effects of information-oriented versus escapism-oriented motivations on the relationship between psychological well-being and problematic use of video game live-streaming services. J Behav Addict. (2019) 8:564–73. doi: 10.1556/2006.8.2019.34, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Di Blasi M, Giardina A, Giordano C, Coco GL, Tosto C, Billieux J, et al. Problematic video game use as an emotional coping strategy: evidence from a sample of MMORPG gamers. J Behav Addict. (2019) 8:25–34. doi: 10.1556/2006.8.2019.02, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Biolcati R, Pupi V, Mancini G. Massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG) player profiles: exploring Player’s motives predicting internet addiction disorder. Int J High Risk Behav Addict. (2021) 10. doi: 10.5812/ijhrba.107530 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychol Assess. (1994) 6:117–28. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.6.2.117 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Sadava SW, Thistle R, Forsyth R. Stress, escapism and patterns of alcohol and drug use. J Stud Alcohol. (1978) 39:725–36. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1978.39.725, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Maraz A, Király O, Urbán R, Griffiths MD, Demetrovics Z. Why do you dance? Development of the dance motivation inventory (DMI). PLoS One. (2015) 10:e0122866. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122866, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Weber M, Aufenanger S, Dreier M, Quiring O, Reinecke L, Wölfling K, et al. Gender differences in escapist uses of sexually explicit internet material: results from a German probability sample. Sex Cult. (2018) 22:1171–88. doi: 10.1007/s12119-018-9518-2 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Masur PK, Reinecke L, Ziegele M, Quiring O. The interplay of intrinsic need satisfaction and Facebook specific motives in explaining addictive behavior on Facebook. Comput Hum Behav. (2014) 39:376–86. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.05.047 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Jouhki H, Savolainen I, Sirola A, Oksanen A. Escapism and excessive online behaviors: a three-wave longitudinal study in Finland during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:12491. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191912491, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Billieux J, van der Linden M, Achab S, Khazaal Y, Paraskevopoulos L, Zullino D, et al. Why do you play world of Warcraft? An in-depth exploration of self-reported motivations to play online and in-game behaviours in the virtual world of Azeroth. Comput Hum Behav. (2013) 29:103–9. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2012.07.021 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Maroney N, Williams BJ, Thomas A, Skues J, Moulding R. A stress-coping model of problem online video game use. Int J Ment Heal Addict. (2019) 17:845–58. doi: 10.1007/s11469-018-9887-7 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Bányai F, Griffiths MD, Demetrovics Z, Király O. The mediating effect of motivations between psychiatric distress and gaming disorder among esport gamers and recreational gamers. Compr Psychiatry. (2019) 94:152117. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2019.152117, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Pontes HM, Stavropoulos V, Griffiths MD. Measurement invariance of the internet gaming disorder scale-short-form (IGDS9-SF) between the United States of America, India and the United Kingdom. Psychiatry Res. (2017) 257:472–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.08.013, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Kosa M, Uysal A. (2020). Four pillars of healthy escapism in games: emotion regulation, mood management, coping, and recovery. game user experience and player-centered design, 63–76. https://www.springerprofessional.de/en/four-pillars-of-healthy-escapism-in-games-emotion-regulation-moo/17870826

- 26. Hussain U, Jabarkhail S, Cunningham GB, Madsen JA. The dual nature of escapism in video gaming: a meta-analytic approach. Comput Human Behav Rep. (2021) 3:100081. doi: 10.1016/j.chbr.2021.100081 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and Meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. (2009) 62:1006–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Peeters M, Koning I, Lemmens J, Eijnden RVD. Normative, passionate, or problematic? Identification of adolescent gamer subtypes over time. J Behav Addict. (2019) 8:574–85. doi: 10.1556/2006.8.2019.55, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Deleuze J, Maurage P, Schimmenti A, Nuyens F, Melzer A, Billieux J. Escaping reality through videogames is linked to an implicit preference for virtual over real-life stimuli. J Affect Disord. (2019) 245:1024–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.078 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Okazaki S. Exploring experiential value in online Mobile gaming adoption. Cyberpsychol Behav. (2008) 11:619–22. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2007.0202, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Bonner J, Allen A, Katsikitis M, Love S, Kannis-Dymand L. Metacognition, desire thinking and craving in problematic video game use. J Technol Behav Sci. (2022) 7:532–46. doi: 10.1007/s41347-022-00272-4, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Cairns P, Power C, Barlet M, Haynes G, Kaufman C, Beeston J. Enabled players: the value of accessible digital games. Games Cult. (2021) 16:262–82. doi: 10.1177/1555412019893877 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Fuster H, Carbonell X, Chamarro A, Oberst U. Interaction with the game and motivation among players of massively multiplayer online role-playing games. Span J Psychol. (2013) 16:E43. doi: 10.1017/sjp.2013.54 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Kaczmarek LD, Drążkowski D. MMORPG escapism predicts decreased well-being: examination of gaming time, game realism beliefs, and online social support for offline problems. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. (2014) 17:298–302. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2013.0595, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Liao G-Y, Pham TTL, Huang HY, Cheng TCE, Teng CI. Real-world demotivation as a predictor of continued video game playing: a study on escapism, anxiety and lack of intrinsic motivation. Electron Commer Res Appl. (2022) 53:101147. doi: 10.1016/j.elerap.2022.101147 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Pyszkowska A, Gąsior T, Stefanek F, Więzik B. Determinants of escapism in adult video gamers with autism spectrum conditions: the role of affect, autistic burnout, and gaming motivation. Comput Hum Behav. (2023) 141:107618. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2022.107618 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Hagström D, Kaldo V. Escapism among players of MMORPGs—conceptual clarification, its relation to mental health factors, and development of a new measure. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. (2014) 17:19–25. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0222, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Kuss DJ, Louws J, Wiers RW. Online gaming addiction? Motives predict addictive play behavior in massively multiplayer online role-playing games. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. (2012) 15:480–5. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0034, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Šporčić B, Glavak-Tkalić R. The relationship between online gaming motivation, self-concept clarity and tendency toward problematic gaming. Cyberpsychology. (2018) 12. doi: 10.5817/CP2018-1-4 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Park J, Song Y, Teng C-I. Exploring the links between personality traits and motivations to play online games. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. (2011) 14:747–51. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2010.0502, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Zaib Abbasi A, Alqahtani N, Tsiotsou RH, Rehman U, Hooi Ting D. Esports as playful consumption experiences: examining the antecedents and consequences of game engagement. Telematics Inform. (2023) 77:101937. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2023.101937 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Li D, Liau A, Khoo A. Examining the influence of actual-ideal self-discrepancies, depression, and escapism, on pathological gaming among massively multiplayer online adolescent gamers. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. (2011) 14:535–9. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2010.0463, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. Lee J, Lee M, Choi IH. Social network games uncovered: motivations and their attitudinal and behavioral outcomes. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. (2012) 15:643–8. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0093, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. Engelhardt CR, Mazurek MO, Hilgard J. Pathological game use in adults with and without autism Spectrum disorder. PeerJ. (2017) 5:e3393. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3393, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. Frostling-Henningsson M. First-person shooter games as a way of connecting to people: “brothers in blood”. Cyberpsychol Behav. (2009) 12:557–62. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2008.0345 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 46. Alimamy S, Shin D, Nadeem W. The influence of trust and commitment on free-to-play gamers co-creation intentions. Behav Inform Technol. (2022) 42:1980–97. doi: 10.1080/0144929X.2022.2105745 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 47. Wischert-Zielke M, Barke A. Differences between recreational gamers and internet gaming disorder candidates in a sample of animal crossing: new horizons players. Sci Rep. (2023) 13:5102. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-32113-6, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 48. McKenna JL, Wang YC, Williams CR, McGregor K, Boskey ER. “You can’t be deadnamed in a video game”: transgender and gender diverse adolescents’ use of video game avatar creation for gender-affirmation and exploration. J LGBT Youth. (2022):1–21. doi: 10.1080/19361653.2022.2144583 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 49. Lee Y-H, Chen M. Seeking a sense of control or escapism? The role of video games in coping with unemployment. Games Cult. (2023) 18:339–61. doi: 10.1177/15554120221097413 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 50. Sauter M, Braun T, Mack W. Social context and gaming motives predict mental health better than time played: an exploratory regression analysis with over 13,000 video game players. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. (2021) 24:94–100. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2020.0234 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 51. Boldi A, Rapp A, Tirassa M. Playing during a crisis: the impact of commercial video games on the reconfiguration of people’s life during the COVID-19 pandemic. Human Comput Interact. (2022):1–42. doi: 10.1080/07370024.2022.2050725 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 52. Liao L-D, Tsytsarev V, Delgado-Martínez I, Li ML, Erzurumlu R, Vipin A, et al. Neurovascular coupling: in vivo optical techniques for functional brain imaging. Biomed Eng Online. (2013) 12:38. doi: 10.1186/1475-925X-12-38, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 53. Lee H-W, Kim S, Uhm J-P. Social virtual reality (VR) involvement affects depression when social connectedness and self-esteem are low: a moderated mediation on well-being. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:753019. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.753019, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 54. Kowert R, Domahidi E, Quandt T. The relationship between online video game involvement and gaming-related friendships among emotionally sensitive individuals. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. (2014) 17:447–53. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2013.0656, PMID: [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 55. Aardema F, O’Connor K, Côté S, Taillon A. Virtual reality induces dissociation and lowers sense of presence in objective reality. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. (2010) 13:429–35. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2009.0164 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 56. Thomas G, Bennie JA, de Cocker K, Castro O, Biddle SJH. A descriptive epidemiology of screen-based devices by children and adolescents: a scoping review of 130 surveillance studies since 2000. Child Indic Res. (2020) 13:935–50. doi: 10.1007/s12187-019-09663-1 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]